Similar Posts

This is the sixth part of an ongoing serial (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5)

In Western churches, liturgical furniture has historically been conceived as an extension of the architecture. In Gothic cathedrals, the choir stalls form an immense integrated construction that is ornamented like Gothic stonework in miniature. The bishop’s throne is surmounted by a vaulted and buttressed canopy, sometimes with spires reaching almost to the roof. In a baroque church, the pulpit is so large and ornate as to completely dominate the nave. A baldachino may stand over the altar like a church within a church. The built-in furniture is an indispensable part of the architecture.

Orthodox churches exhibit an entirely different tradition. Excepting only the iconostasis, eastern churches are furnished with small and moveable furniture. And the furniture does not look like part of the building. In most cases, it is stylistically completely different from the architecture, usually looking more warm and domestic than grand and ecclesial. This is so very appropriate, because the character of an Orthodox liturgy is, in a way, domestic. The faithful are comfortable at church, as though in their own homes. In Greek monasteries it is normal to see the monks resting their arms on lecterns or their foreheads on the stasidia. The furniture is for their comfort and use. It is not there for ecclesial grandeur.

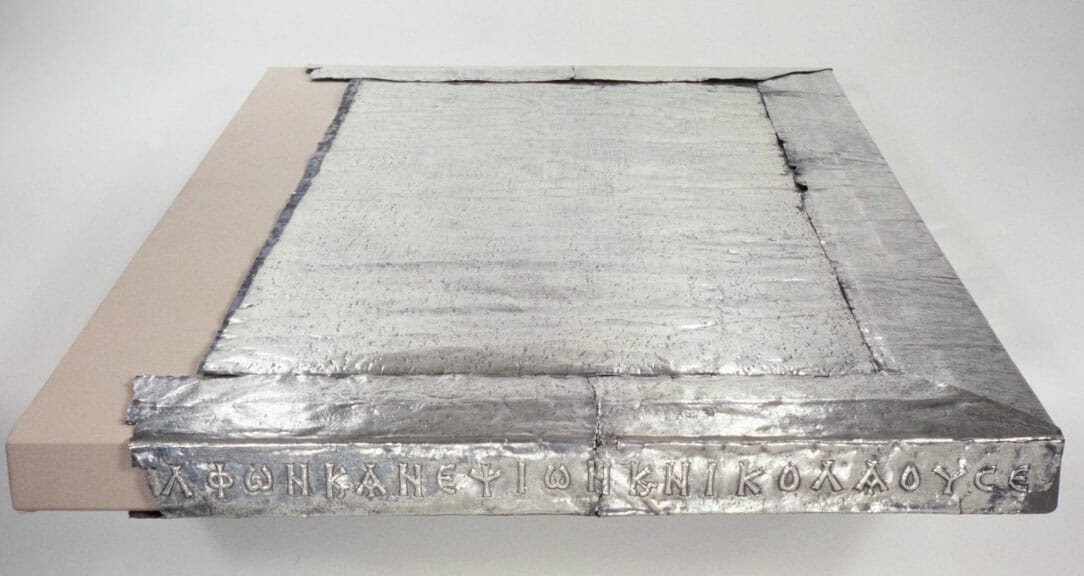

From the earliest days of civilization, the seats of kings and deities have been clad in thin sheets of gold or silver. The Ark of the Covenant, Egyptian tomb furnishings, Roman high places, and Byzantine altars and thrones were made like this. It is known that the templon screen and all the furnishings of Hagia Sophia were covered in precious metals, with the altar in pure gold. Silver furniture is now rare, but there are still a few silver-clad shrines of saints in Orthodox churches, and in Italy, silver altars still exist in many cathedrals. Silver is a soft, warm material, especially when used in large sheets. It is wavy and imperfect and shows uneven patination from years of polishing. The color gradually becomes a warm brownish hue, and it is attractive to the touch. The old silver furniture that survives today is very much approachable and human-scaled, more charming than imposing.

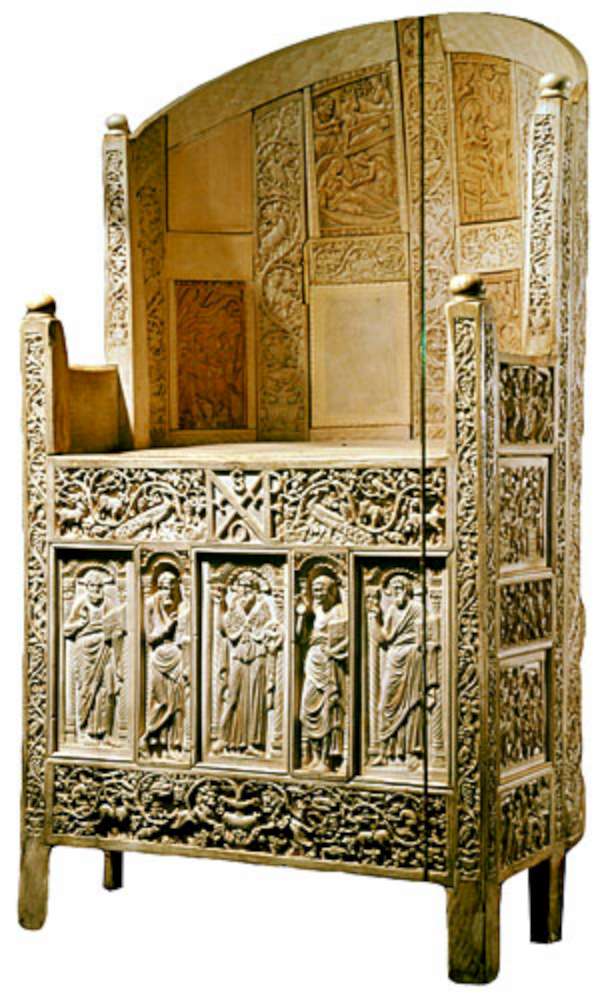

Another Imperial Byzantine craft was furniture veneered in carved ivory. Remarkably, there survives the sixth-century throne of Maximian, bishop of Ravenna. It is wholly clad in ivory panels featuring vine motifs and icons. But again, it is not an imposing design. The chair is small and simply shaped, and the softly carved ivories invite closeness and touch. As in all Byzantine art, the richness of the materials is used to invite rather than to intimidate.

As the availability of silver and ivory waned with the strength of Byzantium, bone, mother of pearl, and tortoiseshell took their place as ornamental inlay. While such furniture occasionally includes crosses or small angels in the ornamentation, it is very often indistinguishable from furniture that one would find in rich Muslim houses or mosques. Evidently, the church did not consider it necessary for liturgical furniture to ‘look Byzantine,’ or to be covered with icons. After all, the furniture is for the comfort and use of the faithful, and there is no need for it to differ from the finest domestic furniture. On the contrary, furniture covered with crosses and icons becomes the object of reverence, which can interfere with its practical purpose.

The inlaid wood furniture which often survives in Greek monasteries is exceptionally warm and comfortable. The flat polished surfaces invite caress far more than carved surfaces and are more practical to keep clean and waxed. The contrasting inlay is very effective ornament for dimly lit churches. Diffuse indoor light is unflattering to relief carving, but not to inlay. The warm color and rich polish of the wood glow beautifully in candle light, and the geometric inlay adds a wonderful sparkle. Byzantine churches tend to favor cool blues and grays in the stonework and frescoes, and this warm wood furniture stands out as a very satisfying contrast.

In Russia and Romania, particularly in village churches, liturgical woodwork grew out of folk traditions. Given the drastic remodeling imposed on Russian churches, hardly any old furniture survives, but enough fragments exist to give an impression. Old Russian furniture favored spindle shapes, which were sometimes elegantly turned on a lathe, and sometimes hewn with an axe like the square porch spindles on log churches. Very often this simple furniture was painted in the same merry colors as domestic folk crafts.

The medieval Russians revived the practice of cladding wood in sheets of embossed silver, and this was frequently done on iconostases and tombs. In the 16th and 17th centuries, a very elaborate style of polychromed woodcarving prevailed, with intricate vines and songbirds painted in red, green, and gold encrusting every surface. Magnificent furnishings of this type remain in place at St. Elijah, Yaroslavl. The deep carving, highlighted in strong colors and gold leaf, is also very effective in dim light. This ‘Old Russian’ (pre-baroque) style of carving is being widely revived in Russian workshops today.

During the Baroque Period in Russia, the decorative arts became more prominent. Iconostases were built with thicker columns and more gilded carving as the icons became less of the focus. While this may be regrettable from a liturgical standpoint, nevertheless we must admit that ecclesiastical ornamentation remained extremely beautiful in Russia in the 18th century. It was not until the early 19th century that Russian artists and architects wholly turned their backs on their native decorative traditions. Churches built in the Neoclassical Era look little different from those built in France. They have the cold rigor of Greek Revival architecture and are devoid of frescoes. The few icons, if one can call them that, are contained in frames like Catholic altarpieces. Furniture suffered equally from this new style. Neoclassical Russian furniture is akin to “Empire Style” work in France. It alludes to the conquests of Napoleon by favoring ancient Egyptian and Greek forms, especially truncated obelisks bearing foreign symbols like the triangle and eye. They are massive, carved of solid marble, or wholly gilded. They are altogether cold and intimidating.

Russia soon repented of this style, and churches from the late 19th-century revived the ‘Old Russian’ forms and ornamentation. A great deal of wonderful medieval-revival furniture was produced at this time, both for secular and liturgical use. Orthodox churches in America did not inherit the benefit of this revival. Always lagging behind the fashions in Russia, American churches continued to favor a poor man’s version of the Neoclassical style well into the 20th century. It is still common for our churches to use white-painted analogia decorated with Greek-Revival columns and cornices. Fortunately, on a small scale and made from wood, such furniture is not so intimidating, but it clearly lacks the warmth and beauty of traditional work.

Today, Russian liturgical workshops labor tirelessly to revive the Old Russian styles of carved and painted iconostases and furniture. Meanwhile, over the course of the 20th century, Greek artisans have developed their own style of carving and furniture design, which they call “Byzantine”. This is the woodwork that can now be seen in almost all Greek Orthodox churches the world over. Unlike the modern Russian work, which is often a very precise imitation of antique examples, the “Byzantine” style of carving is largely a new invention. It is an adaptation to wood of a style of acanthus leaf carving which the ancient Byzantines executed in marble. Originally, this was architectural ornament, such as in the column capitals at Hagia Sophia. Used in wooden furniture, this carving has a rather architectural character. It can sometimes visually overwhelm the proportions of the piece, and can contribute to the imposing effect of some over-scaled Greek furniture. This carving is most effective when used sparingly and mixed with unornamented flat surfaces. In a dimly lit church, it does not read well, and ought to be highlighted with color and gilding, as all medieval carving was. Nevertheless, well done “Byzantine” carving is intrinsically very beautiful, and can serve as excellent ornamentation on well-designed woodwork.

The presence of furniture reveals the welcoming and comfortable aspect of the Kingdom of God. All is not judgment and fear in church. We are called to attend church as though we are coming home. It is so easy for a church (especially a Neoclassical one) to seem to visitors like a museum and courthouse rolled into one. (Don’t touch anything, lest you break the rules, and leave quickly, before you are judged.) Furniture can do much to soften this impression. It should be warm and approachable and invite the touch. And it should be beautiful and fine. If we would not furnish our homes with furniture made from plywood and gold spray-paint, then we ought not to furnish our churches in this way. To be comfortable to touch, furniture must be solid wood with a good polish and wax. It should be light and elegantly proportioned, easy to look at and easy to use. Staining is to be avoided, because it robs light-colored wood of the opportunity to naturally achieve the warm color that comes only with time. Ornamentation, such as carving or inlay, should be integral to the structure, and not glued onto the surface as an afterthought. Above all, church furniture should be true to traditional woodworkers’ standards for joinery and finish, and should have no pretense towards being finer or grander than it is. Good quality secular furniture is often very appropriate in church, and there should be no fear of using it just because it does not bear crosses and eagles. Custom-made furniture can follow any of the old styles, including traditional American styles. Old American furniture has wonderful dignity and simplicity, and is an excellent candidate for the ‘baptism’ of American culture into Orthodoxy.

[…] of the Kingdom of God: The Integrated Expression of all the Liturgical Arts – Part 6: Furniture https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/an-icon-of-the-kingdom-of-god-the-integrated-expression-of-all-th…Friday, Nov 30th 2:39 pmclick to expand…Praying for others […]