Similar Posts

This is the tenth part of an ongoing serial (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6, part 7, part 8, part 9) This essay describes the particular and unique contribution of ceremonial implements to the witness of the liturgical arts in an Orthodox service.

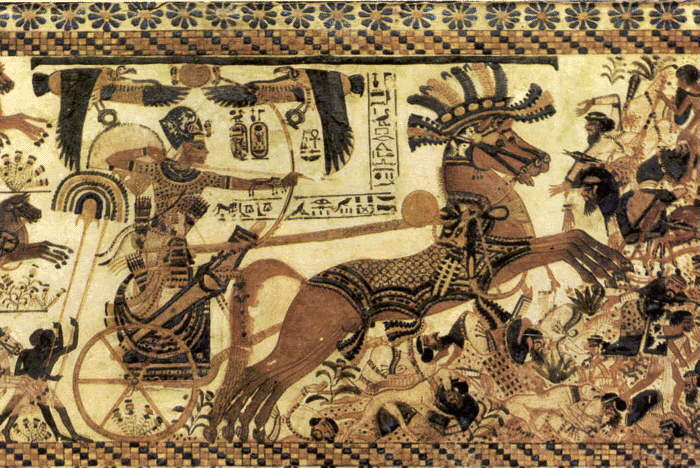

Liturgical fans are the oldest of our ceremonial traditions. Like all things, their most ancient origin was practical. Fan bearers have served kings throughout history, and no doubt this service was initiated for the purpose of keeping them cool and unbothered by insects. But their purpose did not remain merely utilitarian. As early as Pharonic Egypt, the presence of fan-bearers flanking a king became a ceremonial sign of reverence and honor. Egyptian tomb-paintings show fan bearers serving both gods and pharaohs. Thus a simple luxury became an iconographic convention to show who is worthy of honor. It was no accident that fans acquired this greater symbolism. A pair of fans, tall and symmetrical, bearing the many-colored feathers of exotic birds, has an intrinsic ceremonial power. Fans have the upright boldness of battle standards, but they lean inward in deference to the authority of their master. One could contrive no better sign of reverence for a king or god.

Tutankhamun riding a chariot attended by ceremonial fan bearers. Painted on a wooden chest from the pharaoh’s tomb. 14th century B.C.

The purely ceremonial use of fans thus predates Christian worship by many millennia. They were adopted for Christian use not for any mundane reasons related to heat or flies, but because they were a ceremonial symbol whose message was known to all. The oldest surviving liturgical fan dates from the 6th century. It is a metal plate bearing the image of a seraph surrounded by feathers. These metal feathers recall the fan’s ancient prototype which used real feathers to fan the air. But its role has changed; the Christian God has no need of cooling breezes, but sits enthroned upon fiery angels. The fan itself has become an icon of the angels who gather around the Divine Throne—a new and deeper layer of meaning added to an ancient implement. As with all symbols, this secondary meaning (which has perhaps now become the primary meaning) did not arise arbitrarily. It was doubtless suggested by the resemblance of the ancient feathered fans to icons of seraphim.

As the symbolism of fans evolved, their liturgical use evolved also. Fans are no longer mainly used for actual fanning of the gifts. In Russian practice, this archaic function is nowadays performed only by a deacon on the day of his ordination. Fans are now appointed to symbolize the invisible presence of the angels during significant liturgical acts. They are carried in the Great Entrance while the choir sings, “We who mystically represent the Cherubim and who sing the thrice-holy hymn to the life-creating Trinity, now lay aside all cares of this life, that we may receive the King of All, who comes invisibly escorted by the angelic host.” The altar servers take the place of angels, and they carry seraphic fans like soldiers who carry the heraldry of their regiment.

The processional cross likewise enjoys an ancient pedigree. The cross was universally adopted as the sign of victory for Christ’s church in the fourth century. Before his victory at the Milvan Bridge in A.D. 312, Constantine saw the sign of the cross in the sky with the words, “In hoc signo vinces – In this sign, conquer.” The emperor added the Chi-Rho cross to the top of his military standard, and the instrument of Christ’s death transformed into the heraldry of his victory.

Replica of the ‘Labarum of Constantine’ (processional standard with 6-barred Chi-Rho cipher cross at the top).

In liturgical use, the processional cross retains this ceremonial and heraldic duty. It is not meant to be an icon for veneration or contemplation, (as is, for instance, the Golgotha Cross displayed on Great and Holy Friday). Rather, it is the sign of catholicity by which every parish church displays its mystical affiliation with the church triumphant. A Roman legion would carry its aquila (eagle standard) to the ends of the earth to proclaim its imperial authority. Likewise every church carries the cross in procession as the standard of Christ and sign of catholic authority. Appropriate to their heraldic function, the marvelous crosses that survive from Byzantium are large and noble. They have great visual power, with flaring arms and pendant gems, a design exuding confidence and victory. They are often clad in silver with gilded icons, and would glisten in the sun like sharp swords.

Roman soldiers also carried a vexillum, or banner, which displayed the heraldry of their specific regiment. In Christianized Rome, these military banners frequently bore the image of Christ. The liturgical use of banners follows the historical military usage quite closely. Traditionally, a parish has a banner with her titular icon, the local flag of the regiment. Also common are banners with the Holy-Face-not-made-by-hands, the image which Christ Himself sent to King Abgar as the sign of his healing power. Banners frequently display an icon of the Theotokos, protectress of cities and churches, and chief example for all Christians. Banners displaying the archangels and the military saints proclaim the spiritual power of the church to any who might think to oppose it. Arguably, in liturgical use, these banners are a show of force against the demons. But the very same banners were used by Orthodox armies as a show of force against their earthly enemies.

The liturgical processions of the Orthodox Church are modeled upon the procession of military standards that occurred in Imperial Rome. These processions occurred both during festivals and wartime as a demonstration of the glory and might of the Roman legions. The Orthodox Church processes her cross, fans, and banners on great feasts as a display of spiritual power and heavenly authority. It is the glorious sight of the church on earth arrayed in procession in all her strength – a sight which emboldens the hearts of the faithful and weakens the resolve of demons.

The Christian faithful have particular need of bold resolve as they approach the chalice. With fear and trembling they stand before the Body and Blood of Christ and confess to God their total unworthiness. Before the anaphora, the Great Entrance is offered to the communicants to embolden their faith. The gifts are brought out for all to see, not in a spirit of shame for our sins, but in a procession of power and glory. The victory of the church is already accomplished, and her triumph is publicly displayed. By this ceremony, the faithful are reassured that they may approach the chalice without fear of death, for the victory of life is assured.

The modern and pragmatic mind is prone to consider ceremony somewhat dubious. We tend to cling to the archaic origins of fans and banners and dismiss them as tools that once served a purpose which no longer exists. This pragmatism is shallow. Not all liturgical ceremony can be explained as the beautification of prayer and sacraments. Some ceremony is simply ceremony – a celebration of the church’s strength and beauty. We should be in no way embarrassed by the pageantry of the church. Rather, let us recognize that it too glorifies God. Let the church ornament her processions with banners tall and beautiful, emblazoned with large and powerful icons like the battle standards of old. Let her hold them high and confident, for they represent not our glory, but His alone.

Orthodox believers carry church banners during a procession marking the 354th anniversary of the Pereyaslav Council in Kiev.

Thank you so much for this excellent, erudite, and well-illustrated article. The Orthodox Arts Journal is a wonderful publication. I really appreciate your efforts.

I too as Gale appreciate this description. My question is not academic but technical. How is the cross/fan attached to the pole?

On a wooden cross, the pole has a tennon which glues into a hole drilled into the cross. The ancient Byzantine crosses, whether iron or solid silver, would have a tang (tapered flat end-piece) that fits into a slot in the wood pole and affixed with a pair of through-rivets. This, incidentally, is exactly how a sword blade is installed in a wood handle, which further illustrates the connection with military implements.