Similar Posts

Christological and Pneumatological Images of the Church

In early Christian art, there developed a series of complementary visual relationships which I have discussed on numerous occasions and have come to often characterize as the right hand and the left hand of Christ. These elements, like the ass and the ox, St-Peter and St-Paul, the good thief and bad thief in the crucifixion embody concrete meanings in their specific contexts, yet taken globally they weave the coherent visual language of iconography. One of the most potent ways of seeing this basic complementary relationship is as an inward tendency towards unity on one hand and the outward tendency towards multiplicity on the other. The anthropology of Hesychasm can help us quickly grasp this structure, how the inner movement is a gathering of the multiple thoughts and senses into the unity of the heart, whereas in leaving the heart one returns to multiplicity of outer sensations.

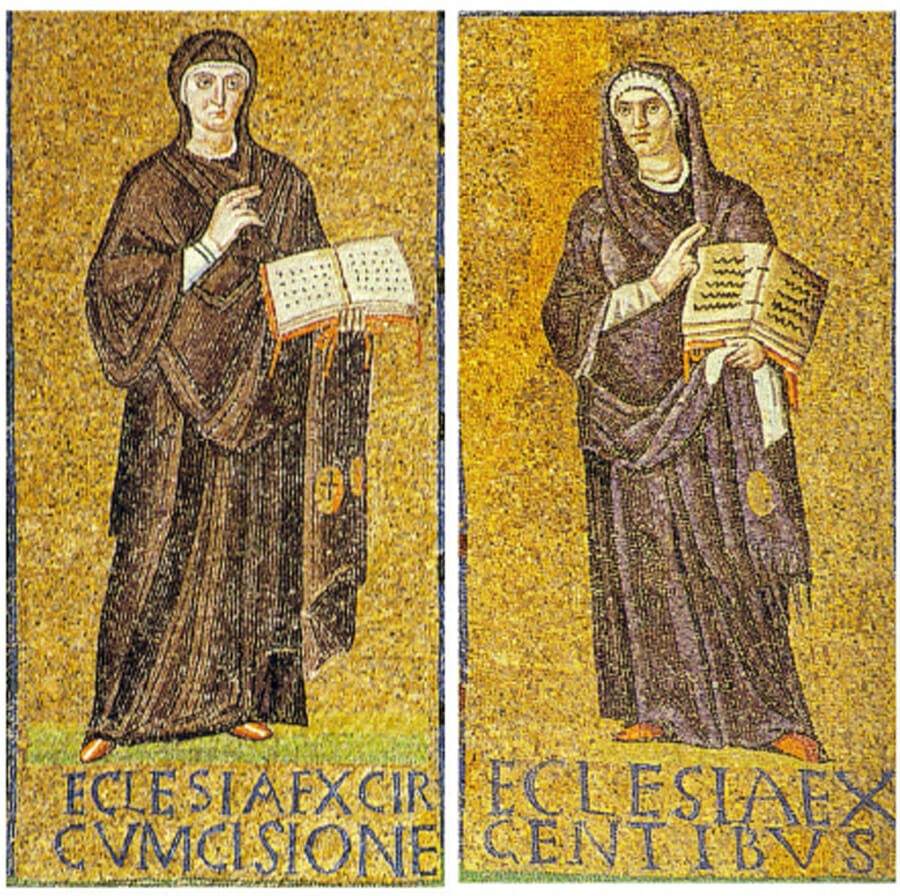

A particular striking visual example of this inner -outer relationship can be seen in a few early Roman mosaics as the dual image of female allegories representing the “Church of Circumcised” on one side and the “Church of the Gentiles” on the other. The two figures are clearly marked as such in a 5th century mosaic at the Church of Santa-Sabina.

In another mosaic from the same time at the church of St-Prudenziana, we also see two women, one crowning St-Peter and the other St-Paul. The women in this mosaic are most commonly interpreted as these two allegories since it is only natural that the allegorical image of the Church of the Circumcised is crowning St-Peter, apostle to the Jews, whilst the church of the Gentiles is Crowning St-Paul its own apostle.

I have discussed this inner outer relationship in terms of Jew and Gentile before, here and here, but in this example the emphasis is even stronger because the inner church is called the church of the circumcised, emphasizing the image of a movement towards the center.

The theologian Vladimir Lossky invokes powerfully this inner and outer tendency of the Church in his Mystical Theology in the chapter “Two Aspects of the Church”. There he frames the duality of the Church in the classical theological categories of nature as opposed to person and simultaneously as Christological as opposed to Pneumatological:

The Church, as we have said, is at once the body of Christ and the fullness of the Holy Spirit, “filing all in all”. The unity of the body relates to the nature, which appears as the “unique man”, in Christ; the fullness of the Spirit to persons, to the multiplicity of human hypostases each one of who represent not merely a part but a whole. [1]

In liturgical art, it is important to understand this complementary relationship of inner-outer movement as a general underlying structure, because although the actual images may have changed over time, (we no longer speak of a church of the circumsised or of gentiles) the basic structure was there long before in the Old Testament and remains at the root of much Christian symbolism today. Not only can we see it in numerous iconographic compositions, this inner and outer complementary relationship is also the basis of the relationship between the liturgy of the word and the liturgy of the faithful for example, or between the inner movement from the nave towards the altar and the outer movement from the nave to the narthex where the catechumen traditionally “departed” after the liturgy of the word. And so these two aspects, one a movement towards the inner oneness and the other as a movement towards the outer multiplicity are in many ways the very shape of the Church. But although together they constitute the Church itself, they must not be equated, must not be confused. They are two terms with opposite yet complementary roles, just as the altar and the narthex function differently in the liturgical shape of the Church building. So many liturgical/ethical/sacramental controversies in the Church today seem to stem from this very confusion, from an incapacity of Christians to differentiate moving towards inner light from bringing light into the outer darkness. It seems therefore important to examine in more detail the ramifications of these two images of the Church.

The Theotokos and other Marys as Images of The Church

As Christianity developed its visual language through the centuries, representations of the Church moved away from allegory to the form of an actual person, the Mother of God. Her image as a “throne” supporting Christ in the apse takes all of its meaning when one sees this in relationship to the image of the ascension where the central column is held by Christ above and the Theotokos below: The head and the body. But in focusing on a concentric or vertical relationship of Christ to his Church, what then happens to the left and right, the inner and outer tendency of the Church? Does it disappear? Of course one still finds St-Peter the apostle to the Jews and St-Paul the apostle to the Gentiles as the two columns, often seen embracing or holding a representation of an actual church building.

Whereas St-Peter and St-Paul are Apostles, that is messengers to the Church, the Mother of God as a feminine image takes on the role of the Materia Prima of the Church, that is the source of the potential of the Church receiving the energies (essences/ logoï) for their manifestations in a way analogous to how she received the uncreated Logos for his manifestation. Ultimately she is the antitype of the primordial waters in the creation account of Genesis on which the spirit of God descends. This makes sense, for if every form of support for theophanies, if every image of space in which God acts in the Old Testament is a prototype of the Holy Mother, then we cannot help but see this culminate into this first original undifferentiated potential. Yet those who have read my last article may be surprised at reading this, because through the guise of the Samaritan woman and the Baptism icon, I explained how the lower waters of Genesis are an image of death, of chaos, the place where monsters and the Leviathan hide. What scandal therefore am I invoking here?

If we look at it carefully, referring to the Tohu-Bohu waters of Creation can actually help us understand one of the most persistently mysterious aspects of the Mother of God: her name. The name Mary means “bitter”, a fact that I have not seen properly explained before because it seems so strange at first glance. The bitter waters are this primordial Ocean, the waters of the cosmos out of which the world takes shape[2]. This undifferentiated potential, through its receiving the command of God, becomes both the place of unity and division for all acts of Creation are simultaneously ones of unifying and separating. Creation is a dividing, for particulars must be pulled out of the undifferentiated, “Let there be a vault between the waters to separate water from water.” (Gen. 1:6), but creation is also a form of unifying since particulars must embody a central identity (logos) around which they are manifested. “Let the water under the sky be gathered to one place, and let dry ground appear.” (Gen. 1:9a)

To return for one moment to the quote by Lossky, In Theological terms, The Mother of God is that image of the Church which invokes unity and Christology, for all the theological importance of the Mother of God is through her role in the manifestation of Christ. As Lossky explains so succinctly in the quote above, Christology is related to nature and the unity of the body. The Mother of God gathered human nature in her womb in the unique person of Christ, so as an antitype of the primordial waters, she is truly that unifying. The primordial waters of Creation can represent untouched potential, just as the Mother of God is pure, virgin and unspotted. Yet opposed to this, the primordial waters can also be an image of chaos in the negative sense, a kind of senseless mixing and the emptiness of death[3]. In this guise we see “bitterness” in ways more intuitive to us. For example, in the story of Ruth, when her Mother in law Naomi is starving in a foreign land where she lost her sons and husband she says ““Don’t call me Naomi,” she told them. “Call me Mara, because the Almighty has made my life very bitter. I went away full, but the Lord has brought me back empty.” (Ruth 1:20) Mara has the same root as Myriam or Mary, that is bitter. Here the emptiness, the emptiness of death, is in many ways the opposite of the virginal emptiness we find in the Mother of God.

Of course in the Old Testament, this movement towards death and chaos is almost always negative, but as we have repeated over and over in other articles, it is represented in Christ as a conquering of death. But if the Mother of God does not embody the lost, the foreign, if she does not embody death, then we must wonder if there is still (considering the two allegories we saw at the outset) an image that is complementary or even opposed to what the Mother of God embodies for us. Opposed to the Most Holy, most pure, ever virgin mother is the loose woman, the prostitute, the prodigal or the foreigner, that one who wandered far away, and whom Christ travels to Hades to find and only then brings back into unity in his body[4]. This is when we must look to the other Marys in our tradition, those who like the “Church of the Gentiles” take on that complementary role.

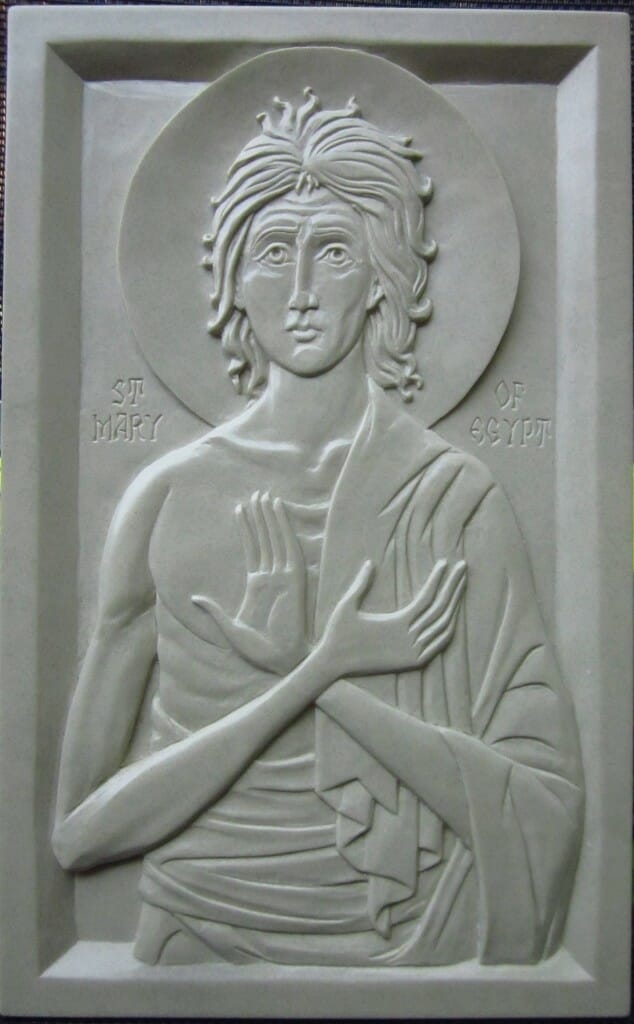

In the Western tradition This “other Mary” was brought about by the famous homily 33 of St-Gregory the Great, where St-Mary Magdalene, St-Mary of Bethany and the adulterous woman in the Gospel were brought together as being one person, that is St-Mary Magdalene . This has received much press in recent years with the unfortunate and silly “Da Vinci Code”. Pope Gregory can be criticized for the creation of the all around character of a redeemed loose woman. But in his defense, this composite figure has played an important role in Western Catholicism, one which has more to do with ontological and cosmic structures than with modern questions of feminism. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, the “other Mary” has truly been St-Mary of Egypt. St-Mary of Egypt embodies all that is opposed to the Mother of God, her extreme life as a prostitute, her being kept outside the Church of the Sepulcre[5], her crossing the river Jordan[6], her being Egyptian[7] but also her uncovered state, her nakedness in the desert “on the other side of the Jordan” as opposed to the Mother of God’s covered purity in the holy of holies of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem.

St-Mary of Egypt is the highest image of a lost sheep, a person who had gone to the edge of chaos and was brought back by Christ. In the West there is a tradition both of Mary Magdalene and St-Mary of Egypt which show their nakedness miraculously covered with a silky golden hair, a sign of this transformation of death into glory. In the persons of the two Marys then we still find, though transformed, that original relationship of the inner and outer Church once represented by the allegories of the Church of the Circumcised and Church of the Gentiles.

Ascension and Pentecost

As I mentioned earlier, the two complementary aspects of the Church which should not be confused appear in several icon types, but if we look at two icons that represent the Church more directly, we will see them with the utmost clarity. These two icons are the Ascension and Pentecost. In the icon of the Ascension, the Church is shown in its utmost Christological form. The top of the central axis is held by the ascending Christ who appears as the head, whereas the Mother of God appears as his Throne, his body, a body that extends to the apostles who are re also looking to their head.

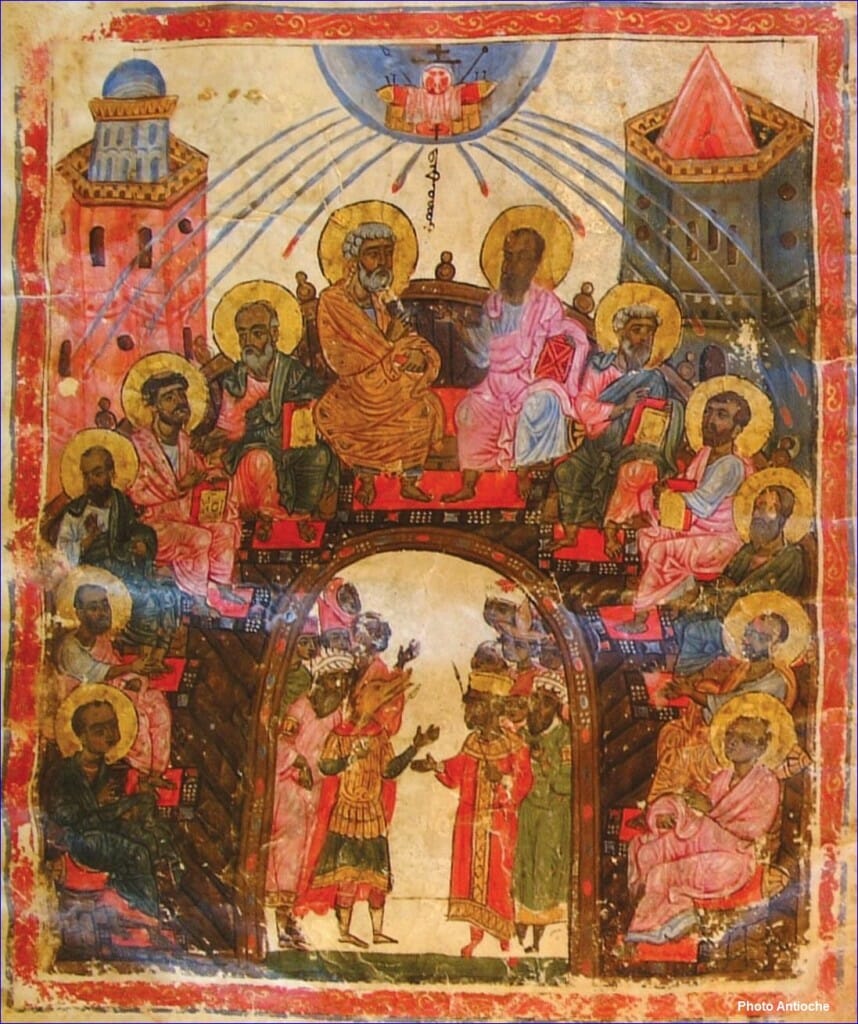

Differently, in the canonical Orthodox icon of Pentecost, Christ and the Mother of God are in fact absent. In the Biblical text, The Theotokos is said to be present, but she is not shown in the icon. This is because the Pentecost icon shows the Church in its pneumatological form, that is in the manner in which the Church moves out into the world. The image of the Spirit in the icon is of this multiplying, as the fire splits up at the top of the icon into twelve rays understood as being one ray for each apostle. The Spirit gives the Apostles tongues of fire, that is causing them to speak in a multiplying language which is understood by all. At the bottom of this icon is an image of Cosmos, an allegorical figure representing all the different peoples of the world. Cosmos holds twelve scrolls , which represent the twelve particular teachings of the apostles mirroring the twelve rays. Cosmos is represented as an old man full of years, standing in the outer darkness.

In early icons, the figure of cosmos was held rather by a crowd of different races and cultures, in Armenian and Syrian manuscripts this crowd often also includes the farthest “dog-deaded” race or even a strange multi-faced monster as the very image of the chaos[8]. Hopefully one will clearly see how the representation of Cosmos or the crowd of foreigners outside the “upper room” reflects something akin to the narthex of the Church. It embodies how the Church reaches out into the fallen world, just as St-Mary of Egypt, or the prodigal son, or the Samaritan Woman. So if the icon of Ascension is the image of the unity of the Church and body looking unto the head, Pentecost is truly the multiplication of the Church, the moving of the spirit unto the ends of the earth.

Serbian Fresco with a wonderful use of the door of Jerusalem which now leads literally outside the Church.The crowd of different nations appear on the outer lower edge.

All of this is important to understand when one is looking to create iconography, because some decisions of composition or typology can impede the underlying structure of icons. Because a basic confusion between inner and outer, between the complementary need for unity and for multiplicity is so pervasive in our society, we must be especially aware of our decisions. Indeed, one of the impetuses for this article was an icon of Pentecost I saw which was made by a prominent contemporary iconographer in which an image of the Mother of God with the Christ child was placed in the icon of Pentecost, not on the usually empty central seat as we sometimes see in Catholic versions of this icon, but rather in the lower door of Jerusalem where we most usually see an image of Cosmos. I think such a change in a traditional icon is very dangerous. I can understand the iconographer’s intuition about the role of Mother God being a form of receptacle in a manner analogous to Cosmos or to the crowd of mixed foreigners, but to replace one with the other is failing to see that they are in fact opposites in essential ways, the one young, empty, pure and untouched, while the other old, saturated and mixed. To be more explicit, confusing these two images is equivalent to confusing a virgin with a whore. Both are images of the Church, but the first is in the middle or the right hand, the original material source of the Body of Christ, while the second is at the edge or on the left hand, the dead body brought back to life by our resurrected Lord.

————————————————————————–

[1] Lossky, Vladimir. The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church. St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1976 p.174

[2] Of course there is a difference between the “undifferentiated waters”, the Tohu Bohu of the first day of Creation and the “lower waters” proper of the second day, but this difference is one of levels as they relate similar realities. For the purpose of this discussion we can see them together.

[3] The ambiguity of the primordial waters is difficult to think about and might be a bit shocking to some, but it is related to the mysterious fact that of all the days, it is only the second day, the day when God separated the waters that He did not say that it was good. The prime example of the ambiguity is how the waters of the flood destroyed the world and returned it to the state of primordial chaos. This chaos only ended when a dove could find a home on earth. This is a repetition of the primordial image of the spirit of God above the waters in Genesis 1 which is itself an image of the spirit of God casting a shadow on the Mother of God at the annunciation, the total and final manifestation of which appears when the dove lands on Christ at his coming out of the waters of his baptism. On this we should not forget that in ancient Christianity both the Nativity of Christ and his Baptism were celebrated at Theophany.

[4] This aspect of the Church is found also prefigured in the Old Testament with characters such as Rahab, Ruth, the prophet Hosea marrying a prostitute and several others. Interestingly enough, in the New Testament, the word for Gentile, the “Goy” of the Old Testament is translated by “Hellene”, a fact that should not be ignored. By using “Hellene”, the Bible refers not only to the foreign nations, but the people of “Helen”, that Helen of Troy, the mythical cause of the Trojan war, the unfaithful woman who left her husband for a foreign prince until the Greeks had to go get her back.

[5] The fact that this was the Church of the Sepulcre is important because of all the Marys who came as myrrh bearers to discover the tomb empty in the Gospels.

[6] For the symbolism of the edge and the crossing of rivers, see my article on St.Christopher.

[7] For Egyptians as an image of the passions, garments of skin and the uncircumsised state see Gregory of Nyssa, Life of Moses II, 38-39

[8] This notion of a mix of foreigners is a Biblical image found in the Book of Exodus, where it is said that a mixed multitude were with the nation of Israel in the desert, See for example exodus 12:38

Hello, I really enjoyed this article and would like to print it off so as to reread its contents because it is so rich and profound.

Would it be possible to perhaps send it to me via email in a Word document or a .pdf file format for easier printing?

My private email address is mentioned, of course (uema_schneider@yahoo.fr).

Thank you very much & God bless you!

* Maria S. *

The easiest way to do this is to get Evernote, and install the browser plugin. Click on the Evernote icon, and select “Simplified” article. This will save just the article itself, stripping out the left and right columns. You can then print it out.

Or, just position your mouse over “Two”, hi light the article down to the last footnote, then right-click and select “Copy” and paste into a new Word document.