Similar Posts

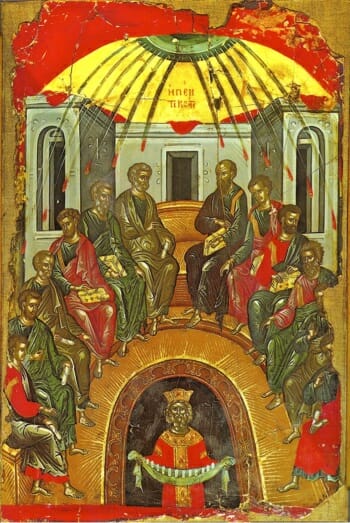

15th century icon of the ascension from Russia

This post is the second part of a series. Part one: Mercy on the Right, Rigor on the Left, Part Three: Authority on the Right, Power on the Left

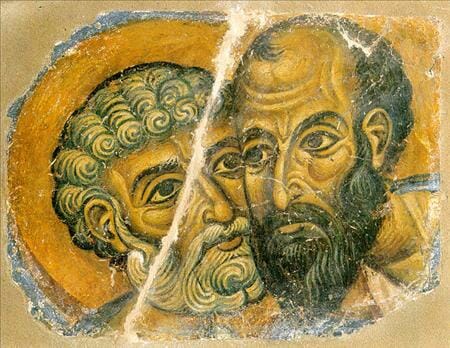

The iconography of St-Peter and St-Paul is one of the most stable and most ancient in Christian art. Even before the image of Christ became fixed, one could recognize Peter and Paul: St-Peter having short white hair with a round curly beard whilst St-Paul is a balding man with a dark pointy beard. The motif of St-Peter and St-Paul flanking the right and left of a scene is so pervasive that often St-Paul will appear in his usual place even in scenes where he was not physically there. This is true of the Ascension and Pentecost.

Yet before we dive in too deeply, we need to mention one thing regarding symbolism of the left and right hand. Because the right and left depend on the point of view, where my right meets your left when we face each other, confusion can quickly set in.

We should not be surprised of exceptions or inversions in some icons as these are not at all rare[1]. What is important is that these two sides represent the same thing even when they are inverted through an interpretation of the point of view. As Christian imagery stabilized and in most iconography since then, what is the “right” is taken from the point of view of Christ in the image, appearing therefore on the viewer’s left. This remains true even when Christ is not there. For example in the icons of Pentecost, both saints will retain their traditional sides despite that Christ is not visibly there to anchor their position. I contend that almost unanimously through all of iconography, Peter and Paul are identified with what we could call the “symbolic” right and left side respectively.

Very early, from the time of St-Clement of Rome, St-Peter and St-Paul have been hailed as the two Pillars of the Church. On a 5th century image from Saint-Sabina in Rome there appears a proto-ascension, with Christ in glory at the top and with Sts Peter and Paul grasping a chrism over the head of a figure that is most probably Ecclesia, a symbolic figure standing for the church (This figure will later be joined to the symbolism of the Holy Virgin.) It is in this respect, as the two pillars of the church, that they appear in so many images culminating in the icon of the saints holding a church together as a symbol of their role, incarnating in a way the two basic principles of the constitution of the Church.

To understand what I mean by this last statement, we need to review the basis of left/right symbolism in the New Testament, the passage in which Christ separates the sheep and goats (which we have looked at in our post on Mercy and Rigor). In the Gospel passage, we find not only a separation into opposing sides, but to the sheep on his right Christ says “come” and to the goats on his left he say “depart”. The movement is not only a separation, but a movement towards and away from Christ. This aspect of the symbolism of left and right is supported by early rabbinical traditions in which God is said to “bring closer with the right and push away with the left”.

We need to view this movement of coming closer and moving away in the spirit of Tradition and with the mind of the Fathers. In the tradition of the Philokalia, the “moving in” of the nous is a concentration, a movement towards unity and the solidity of the heart, whereas the “moving away” is a dissipation, a movement towards multiplicity , the senses and corporality. Relating to this, there is an ancient tradition coming from Evagrios that the right eye is meant for contemplating God whilst the left eye is meant for contemplating created things[2]. Consequently, the first reason for the left /right position of the saints is the same as what we have described in an earlier article about the symbolism of the ox and ass in the Nativity icon representing Jews and gentiles. Here we have st.Peter, the apostle to the Jews, and st. Paul the apostle to the gentiles. Peter is associated with a “gathering in” or “founding” whilst Paul is associated with a “spreading out”.

To help us understand, we can look at an Old testament type prefiguring the Apostles in their role as “pillars”. In the Temple of Solomon there were two prominent bronze pillars. These pillars are given names in Scripture. The first pillar is Jachin, which means “the Lord will establish” . This notion of establishing can be linked to our Lord telling Peter: “You are Peter and on this stone I will build my church.” The second pillar is called Boaz, and here we have an even more surprising relationship, because although the word Boaz has an obscure etymology, it refers to the ancestor of David known mostly for marrying Ruth, a gentile woman who converted. Boaz therefore strongly prefigures Paul as the “apostle to the gentiles”. Most importantly, just as with Peter and Paul, we can see in the two pillars of the first Temple this primordial movement towards and away from the center, analogous to the movement of the nous.

As always these relationships we are exploring are deeply noetic and it is difficult to fully analyze them as they must be grasped in an intuitive manner. In the modern world, our capacity to experience this connectivity of meaning is greatly diminished. But there remains traces of these ancient meanings still today, for even in our modern languages “right” also means “correct” or “good”. In French “droit” has the meaning of “straight” just as in the greek “ortho”. In several languages, “left” has a meaning of awkwardness, crookedness, the root of the English word “left” means “weak, foolish”. In latin, even the darker aspects of the left hand appears as it is called “sinistre”. This symbolism is closely attached to our everyday experience as most of us have one hand that is dexterous and one hand that is awkward, one hand that is strong and another that is weak.

Yet having said all I have said, one must be careful not to simply think that right=good and left=bad. In fact St-Maximos tells us “The passions of the flesh may be described as belonging to the left hand, self-conceit as belonging to the right hand”. Here we can see the same symbolism continuing, with self-conceit being a sin of solidity while the passions of the flesh bringing about sins of dissipation. St-Maximos also tells us that “

“Demons that combat us by the lack of virtue are those that teach us prostitution and drunkenness, greed and jealousy. The demons that combat us by excess of virtue are those that teach us presumption, vain glory and pride, and who, by the vices of the right secretly place in us the vices of the left. »[3]

We can see this movement of the “vices of the right” in the very person of St-Peter, for his sin was not firstly to have denied Christ, but to have announced that he would never deny him. And having declared his infallibility, Peter quickly flips over to the “left side” and is in fact the only apostle to ever deny Christ!

If we can see the “negative side” of the right in Peter, we can also perceive the “positive” side of the left in the person Paul. St-Paul is a perfect picture of the “left hand”. Firstly, he is in a way “added” to the 12 apostles, his legitimacy must be questioned before he becomes the 13th apostle. He calls himself the “least” of the apostle. He boasts of his weakness, he calls himself a fool, he tells us that he is a “shape shifter” being all things to all men. He is a Roman citizen, something we often take for granted, but which places him on the cusp of being a gentile himself. Yet in St-Paul we can see how all these left hand attributes contribute to the life in Christ.

12th century icon of the embrace of St-Peter and St-Paul. According to tradition, the two saints embraced before being executed.

In the end, what is important is how the left and the right are connected to the heart, how in truth, the Church is neither of Paul nor of Peter but of Christ. When contemplating the icon of the embrace of the apostles, we should tremble at the possibility of them having gone their separate ways. We should tremble at the very fantasy of St-Paul creating a fragmented, illegitimate, informal, proselytizing church opposing an overly centralized, presumptuous, formalistic church in this imagined wake of St-Peter. Rather, as they have embraced, as they continue to embrace in the very bosom of Christ, we find two immovable guides, a pillar of cloud and a pillar of fire, one pointing to the gathering, the communion of faithful, the joining of the body, the stable and solid hierarchy of the church; and one pointing to Christ’s great commission, the announcing of the Word, the martyrs, the ascetics and those fools of God that sacrifice all for Christ.

This post is the second part of a series. Part one: Mercy on the Right, Rigor on the Left, Part Three: Authority on the Right, Power on the Left

[1] Gregory Melnïck in his translation of the a Russian icon pattern book, the « Bolshakov manual » mentions this confusion regarding the Russian cross with three horizontal bars : « From time to time one sees « three-barred » crosses appear to be « reversed », that is, the bottom bar ascends from left to right. …The Slavonic text is misleading because it assumes the reader understands that « left » and « right » are actually from Christ the Savior’s perspective and not the viewer’s. » p.30

[2] See for example the bottom pag not e, p. 114 in “Les Récits d’un pèlerin russe.” Translated into French by Jean Laloy. Bracconière/Seuil. 1966

[3] St-Maxime le confesseur, centurie V sur la théologie, parag. 77, in the Philocalie, p.507 (my translation from french)

Manna from Heaven & Flesh from the Sea.

A glimpse of the left and right can also be found in the Exodus when manna is given to the Israelites. There are two accounts: (1) Exodus ch. 16 and (2) Numbers ch 11. The first account is focused on “manna” and the second on “flesh” (in the form of quails from the sea). There is a definite right-left duality to be found: Manna is described as “white” and as “frost” while Flesh is red and warm; manna is found at dawn while the quails (flesh) are found at dusk. Manna comes from Heaven while the quails come from the “sea” (or the west-Egypt).

Further: manna is said to resemble the coriander “seed”. The notion of “seed” is a clear reference to the pure and simple logos (or law). Manna is also defined as their core nutrition: they are only allowed to gather what is strictly necessary each day (anything ‘left’-over will quickly turn to worms… in this case too, excess of the right becomes left).

The description of “flesh” (in Numbers.11) is also quite revealing and makes the duality very clear. It is connected to the “mixed multitude” and carries with it a kind of punishment: “You shall not eat one day, nor two days, nor five days, neither ten days, nor twenty days; but a whole month, until it come out at your nostrils, and it be loathsome unto you; because you have rejected the Lord who is among you, and have troubled Him with weeping, saying: Why, now, have we come out of Egypt?”.(v.20) And later: “While the flesh was yet between their teeth, the anger of the Lord was kindled against the people, and the Lord smote the people with a great plague. (v.33).”

Even more interesting is that part of the flesh narrative (Num 11: 13-17) is directly connected to the dissipation or dispersion of the authority of Moses. The spirit of God that was given to Moses has to be spread out into 70 elders on account of this demand for flesh. And so the giving of flesh comes with decentralization and a spreading out of the spirit:

“Whence should I have flesh to give unto all this people? for they trouble me with their weeping, saying: Give us flesh, that we may eat. I am not able to bear all this people myself alone, because it is too heavy for me…. And the LORD said unto Moses: Gather unto Me seventy men of the elders of Israel… And I will come down and speak with thee there; and I will take of the spirit which is upon thee, and will put it upon them; and they shall bear the burden of the people with thee, that thou bear it not thyself alone”.

Moses himself appears as a kind of “right pillar” in this story which cannot bear the people alone on account of their need for “flesh”. There is also the need for a “left pillar” alongside Moses. The left is often found in the person of Aaron (e.g. the golden calf incident) or in the transfiguration, with Moses on one side and Elijah on the other.

Thanks for that. It goes so well with the insistence I have been putting on left hand representing flesh. I usually forget that the quails in the desert were a “condescension” and come with consequences. Thinking in that direction opens up a whole area, and we can see how in the same vein, the permitting of eating meat coming after the flood is also the same kind of condescension, with all of these images pointing to the incarnation as the ultimate “kenosis”, lowering. It also gives a wider vision of “bread becoming flesh” and the whole notion of Abel being united with Cain that comes with the incarnation!