Similar Posts

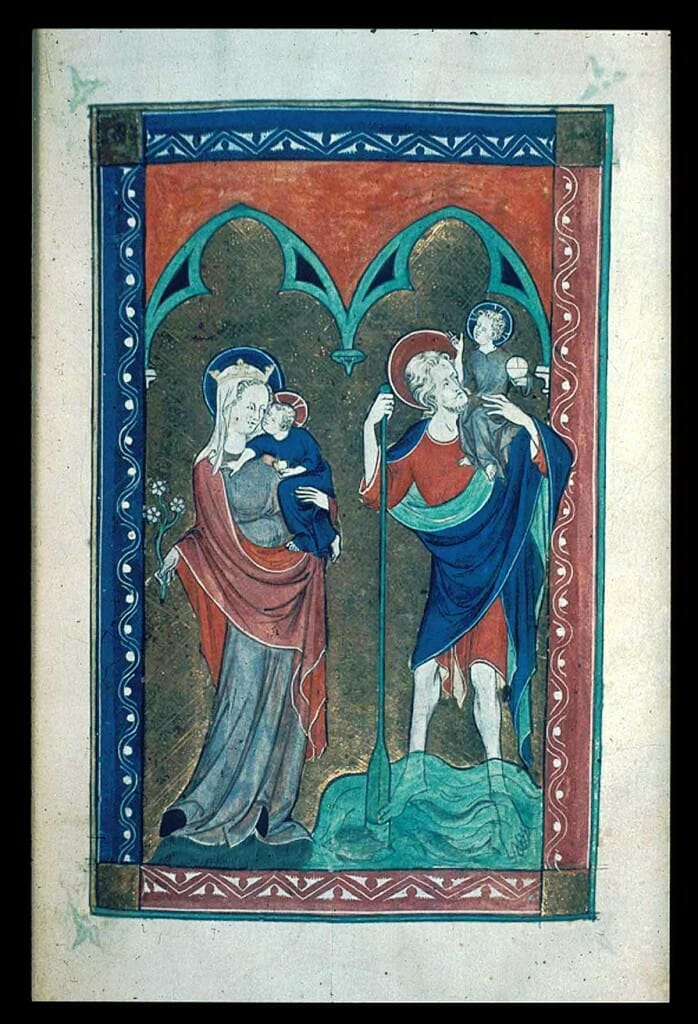

17th century icon of St-Stephen and St-Christopher

This post is the first of a series. Part two

The icon of St-Christopher is one of the most astounding images found in the Orthodox Tradition. Showing a dog-headed warrior saint, it conjures fantastical stories of werewolves or of monstrous races from Pliny’s edge of the world. Because of all the difficulties it presents, the icon was proscribed in the 18th century by Moscow.

The Orthodox icon of St-Christopher presents him as a warrior cynocephalus, a dog-headed man from Lycea. Sometimes he is also of gigantic size as well. According to his tradition, he was a Roman soldier taken from the far end of the world who converted and was martyred by an Emperor.

In the Roman Catholic Church, the feast of St-Christopher was suppressed entirely with Vatican II modernization, though he continues to be one of the most popular saints in Catholicism — his image adorning the dashboard of cars all over the world. I believe understanding St-Christopher and his iconography is of prime importance today, and hopefully it will become clear why as we travel through the Bible, Tradition and iconography to see if we can decipher this saint who is such an affront to modern sensibilities.

Western images of St-Christopher present him as a giant Canaanite who’s main story has him helping people cross a river by carrying them on his back. One day he crosses a young child who becomes heavier and heavier as Christopher advances in the water, so much that he is afraid he will drown. Upon asking the child why this is so, Christopher discovers the child to be Christ, hence his name: Christopher, the “Christ-carrier”[1].

Iconography of Monsters

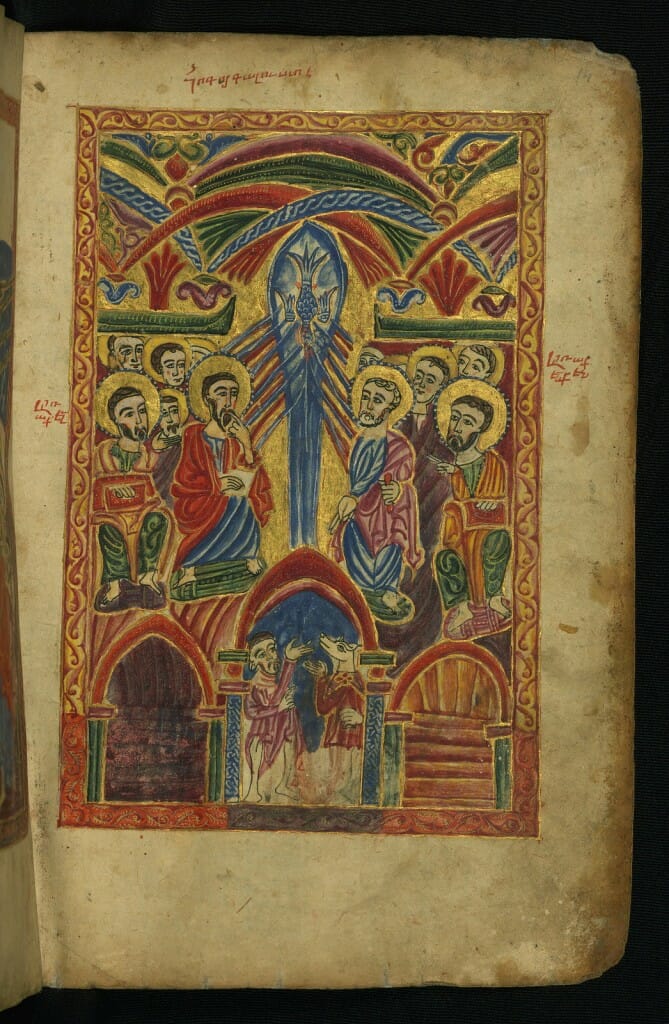

The use of dog-headed men in iconography is not limited to the icon of St-Christopher. They also appear most commonly in images of Pentecost, prominently in Armenian manuscripts, but also in Western images.

Manuscript illumination of Pentecost with a dog-headed man

The Dog-headed men are seen as the farthest race present at Pentecost. Because they are the farthest, in some Armenian images they appear in the center of the door or else they appear alone, representing a distilled image of the ultimate foreigner. There are some other images, for example a well-known image where dog-headed men are represented as the Barbarian enemies who threaten Christ. Sometimes they are seen as one of the races encountered in the mission of the Apostles.

Christ surrounded by Cynocephalic warriors. Kievian Psalter. 15th century

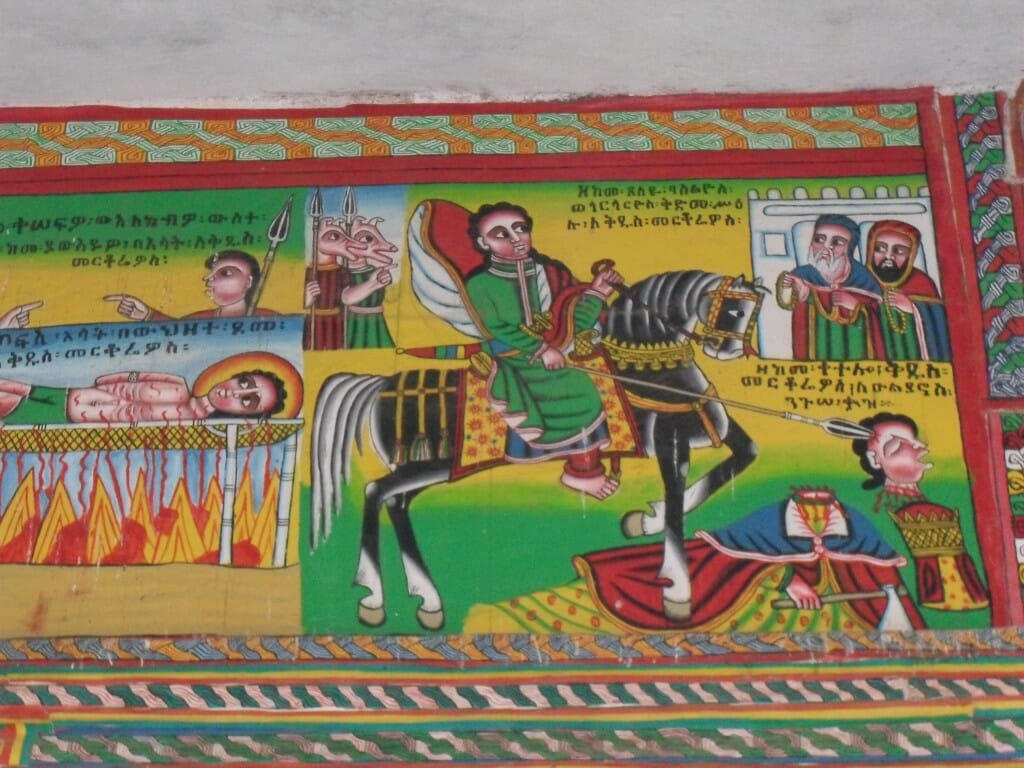

Finally, dog-headed men appear in the story of St-Mercurios[3], a warrior saint who’s father was eaten by two dog-headed men later converted by St-Mercurios. These dog-headed men’s savage nature could be unleashed by St-Mercurios on the enemies of the Roman empire in a way analogous to how Romans and later Christians used Barbarians in their own wars. The most obvious examples of this is how the recently converted Germanic Barbarians stopped the advance of Islam into Europe or how the recently converted Scandinavian prince of Kiev provided the Emperor in Constantinople with a personal Varingian guard.

The tradition of St-Mercurios is alive and well in Ethiopia, where I documented these contemporary images of St-Mercurios and his two companions on the outside of a church”

These iconographic examples show the dog-headed men as representing barbarian foreigners par excellence, those living on the edge of the world, the edge of humanity itself. They are cannibal, savage, hybrid creatures who later will be conceived as descendants of Cain fallen to a monstrous state. The giant Canaanite of Catholic images, who has now often integrated Orthodox iconography, though less visually shocking for having lost his monstrous face, signifies the same reality as Dog-Headed men. The giants in the Bible and in Christian tradition are often also interpreted as descendants of Cain and monstrous cannibal barbarians, who by their excessive bodies represent the extreme of corporality itself.

The relation of the foreign and marginal with excessive corporality, animality and disordered passions like cannibalism must be seen within a general traditional understanding of periphery. In a traditional view of the world, there is an analogy between personal and social periphery, both pictured in patristic terms as the garments of skin, those garments given to Adam and Eve which embody corporal existence. What appears at the edge of Man is analogous to what appears at the edge of the world both in spatial and temporal terms, so the barbarians, dog-headed men or other monsters on the spatial boundaries of civilization and the temporal end of civilization are akin to the death and animality which is the corporal spatial limit of an individual and the final temporal end of earthly life. The monsters as part of the garments of skin dwell on the edge of the world, and though they are dangerous, like Cerberus at the door of Hades, they also act as a kind of buffer between Man and the outer darkness. Just as our corporal bodies and its cycles are the source of our passions, they are also our “mortal shell” protecting us from death. It will therefore be by a more profound vision of the garments of skin across different ontological levels of fallen creation that we can make sense of St-Christopher[4].

St-Christopher in the Bible.

The relation of the Dog to periphery appears several places in the Bible. Dogs are of course an impure animal. They are seen licking the sores on Job’s skin[5]. They are excluded from the New Jerusalem[6]. They eat the body of the foreign queen Jezebel after she is thrown off the wall of the city[7]. The giant Goliath himself creates the St-Christopher dog/giant/foreigner analogy when he asks David: Am I a dog that you come at me with sticks?[8] The dog is used by Christ as a substitution for a foreigner when he tells the Samaritan that one should not give to dogs what is meant for the children[9]. The answer of the woman is also telling as she speaks of crumbs falling off the edge of the table, clearly marking the dog as the foreigner who is on the edge. Just these examples might be enough to explain St-Christopher symbolically, but there is still more.

The key to finding St-Christopher more profoundly in the Bible is the story of his crossing the river. In Scripture, there are several significant stories of water crossings, and through these appear the essential elements of the St-Christopher story as it relates to periphery and the garments of skin. As we search we must remember the movement of the garments of skins being both death and cure for death, both the cause of and the solution to the world of the fall. This means that the symbols will all be there in the different stories, but they can sometimes slip from one side to the other. The first example comes in the flood story, where Noah builds an ark, a shell full of animals to escape the world of fallen giants[10]. Then in the crossing of the Red Sea, the Israelite mix with a host of foreign nations to escape the foreign Egyptians[11]. This last one might not seem as clear, but it becomes so upon the next “crossing”. When the mix of Israelite and foreigners coming from Egypt finally do cross the Jordan to enter the land of the Canaan where the giants live, there are only two people left of the adults in the original group. Of all those who fled Egypt, the only adults from the original group who cross the Jordan as the Ark of the Covenant separates the waters are the two spies Joshua and Caleb[12]. Joshua, which means “savior”, is of course the name Jesus, and he would become the leader of Israel as they enter Canaan. As for the other fellow, one of the meanings of the name Caleb is “dog”. This meaning is emphasized in the text because Caleb is a foreigner, a Kenizite who is said to have been given the periphery, “the outskirts” of the land taken by Israel[13]. And so here we have two people entering the promised land, crossing the Jordan, Jesus and the Dog, Christ and the Foreigner, the “head” and the “body”. The term Kenizite, is one of those terms that will annoy modern scholars when I mention that it also has the “K-N” sound of Cain, Canaan, and Canine – just a coincidence worth mentioning.

The next examples of water crossing that will bring all of our discussion back on itself are the Jordan crossings of Elijah and Elisha[14]. This happens in the same place as their ancestors, near Jericho, the first city taken by Joshua. Elijah uses his garment, which was a “hairy garment”[15], a garment of skin, to separate the waters and then leave this world bodily (just as Enoch did before the flood and Moses did before the entry into Canaan), and then Elisha, having received Elijah’s garments with a double portion of his power, used the garments of skin to return to the side of Jericho. This story is of course symbolically linked to the flood and the Ark, as well as to the crossing of Joshua and Caleb with the Ark of the covenant, and so when we put all of these together we have: giants, garments of skin, arks, dogs, foreigners, and “the savior” who wields all these things in order cross the chaotic waters. What we have before us is an image of baptism, but in a deeper way the image of St-Christopher with Christ on his back crossing the river is also an image of the Church itself.

Elijah ascends as Elisha grabs on to his garments of skin. Icon from Novgorod.

The relation between the crossing of waters and baptism is brought out in several stories of the New Testament, but regarding St-Christopher and the relation of the Church to the foreigner, we must look at the story of the Ethiopian eunuch[16]. Of all the conversions in the early Church, St-Luke chose this story for a reason. The full meaning can only be understood if we know what an Ethiopian and a Eunuch meant in the ancient world. Eunuchs played a role very similar to what we have been describing all along. Just like dogs, they were excluded from the temple. By castrating themselves they became strange hybrid creatures, neither male nor female. They were outcast, sterile and without descent. This is of course bolstered by the fact that eunuchs were often slaves. But because they had no place in society, no posterity to favor, they often became the “guards” of royalty or emperors. Even until Justinian, it was not rare to find a “buffer” of eunuchs around the emperor protecting his person and his affairs. Foreigners could also play this role, as the Varingians I mentioned earlier. This of course is the role of our Ethiopian Eunuch, as he is said to be responsible for the treasure of the queen of Ethiopia. Ethiopia in the ancient world was the home of the far away races, monstrous races even, and was the original land of the Sphinx. The detail that the Ethiopian was of the court of Candace, queen of the Ethiopians is meant to evoke for us the queen of Sheba who came to pose her riddles to Solomon. And so our Ethiopian Eunuch represents all of what the garments of skin represent. And just in case some doubts linger, an interesting detail in the story may convince. It is said that after Philip baptizes the Ethiopian, “The spirit of the Lord caught away Philip, that the Eunuch saw him no more”… This is of course the same phrase as in the story of Elijah and Elisha, that after Elijah ascended, Elisha “saw him no more”. The use of the same phrase is there to remind us of the connection, of how the story of the Eunuch and his baptism is related to all the “water crossing” stories I have mentioned, many of which have someone ascending as part of them, all of which have as a “vehicle” for the crossing some aspect of periphery, some image of the garments of skin. This ascending and leaving behind a “body” is also related to the Ascension of Christ leaving behind him the Church.

Philip and the Ethiopian Eunuch from the Menologion of St-Basil

There are many other stories, taken even from other cultures, where this structure appears. From Odysseus’ encounter with the Cyclops, the giant “Little John” fighting Robin Hood on a river to the three billy goats gruff, examples abound showing how deep and noetic the story is in human experience. The most recent clear example of this structure is the very successful book “Life of Pi”. As is usual in contemporary story telling which wants to push things further, here the movement of the garments of skin is brought to its extreme. In order to assure his “crossing”, the main character must rely on cannibalism imaged as a Tiger in the bottom of his boat. Cannibalism is of course one of the most common attributes given of the monstrous foreign races and is a very strong image of death.

Hopefully our trip will have proven how rather than simply being a series of accidents and exaggerations, the basic story and iconography of St-Christopher are perfectly coherent with Biblical narrative and tradition. Whether the dog headed warrior or the river crossing giant, both strains of iconography point to the deep meaning of flesh being a carrier of Christ, being “christophoros”, of the foreigner being the vehicle for the advancing of the Church to the ends of the Earth. Indeed, the story of St-Christopher is in fact an image of the Church itself, of the relationship of Christ to his Body, our own heart to our senses, our own logos to its shell.

Despite all of this, in the end, the big objection is still lingering: Yes, these stories are well and good, but in our savvy scientific age, no one believes in dog-headed men and races of giants anymore. St-Christopher remains an embarrassing trace of mistaken belief held in the past and should, for that reason alone, be sidetracked.

In my next article therefore, I will try to take the reader on an encounter with St-Christopher.

Fresco of unknown origin showing St-Christopher as a mix of his eastern and western stories.

[1] The most complete version of this story is in the Golden Legend: http://www.catholic-forum.com/saints/golden234.htm

[2] David Woods, the Origin of the Cult of St-Christopher, 1999

[3] For an account of the legend, see Myths of the Dog-Man by David Gordon White, p.37-38, The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

[4] For a general treatment of the Garments of Skin in St-Gregory of Nyssa and other Church Fathers, see my article on the subject : http://pageaucarvings.com/2/post/2012/9/the-garments-of-skin.html

[5] Job 30:1

[6]Rev. 22:15

[7]2 Kings 9: 33-37

[8] 1 Sam. 17:43

[9] Mat. 15:26

[10] Gen. 6-7

[11] Ex. 14. The Egyptians are seen very explicitly as symbols of the garments of skin by St-Gregory of Nyssa, relating them to the general notion of the foreigner and foreskin. See for example Life of Moses, book II, section 38-39.

[12] Num. 14: 29-30

[13] Joshua 21: 11-13

[14] 2 Kings 2

[15] 2 Kings 1:8

[16] Acts 8: 26-40

Thank you for your excellent article on Saint Christopher. While the saint’s feast is unfortunately no longer celebrated by the universal Church on its liturgical calendar, he has not been “suppressed” as a saint. He has fallen off the calendar like other long venerated figures (Valentine, Barbara, Margaret of Antioch, etc.) to make way for more modern saints. Perhaps one day he will be reinstated as was the case with Catherine of Alexandria. Such saints have made a huge impact on the history of Christian iconography. May they continue to do so!

As usual, Jonathan, you’ve managed to take a obscure bit of iconography and turned it into an astonishingly interesting history of the world. Well done!

Another example of human beings from distant places being shown with animal heads is found in the lower tier of the tympanum of the Basilica at Vezelay: http://www.flickr.com/photos/jimforest/3688853217.

The tympanum of the central portal leading from the narthex to the nave is dominated by the figure of Christ in majesty within a mandorla that reveals him to be the second person of the Holy Trinity. Christ is sitting on a throne, knees turned to the right. He has a halo with a cross on it, and wears a long, graceful garment with many folds. His feet are bare, emphasizing his having become incarnate – God become man, leaving his footprints on the earth. His arms are outstretched beyond the edges of the mandorla. Rays of divine light connect him to the twelve smaller figures – the apostles – who are ranged on either side. The theme is the commissioning of the apostles to bring the good news of the Gospel to all people. To suggest the variety of peoples to whom the Gospel will be brought are the smaller figures on the long tier just over the doors – from pygmies, who need a ladder to climb onto a horse, to people with immense ears or strange heads.

Thank you for your article. I love that the Orthodox Arts Journal focuses on the beauty of Christianity. However, I do have one question concerning this article’s conclusion. It ends after taking us brilliantly through the history of the icon by stating, “Indeed, the story of St-Christopher is in fact an image of the Church itself, of the relationship of Christ to his Body, our own heart to our senses, our own logos to its shell.” Despite this, Jonathan Pageau still believes, “St-Christopher remains an embarrassing trace of mistaken belief held in the past and should, for that reason alone, be sidetracked.” So, my question is, isn’t this a slippery slop? It seems that we could, if we wanted, set aside almost all symbolism with Christianity (whether it be found in the theatrics of liturgy, the images of art, or the sounds of music) with the excuse that we are all too savvy in this technological age. Instead of sidetracking Christian symbolism, shouldn’t the answer be education and learning how symbols point to something beyond themselves?

Your comment is of course exactly right on target, and the vision you propose is what I have been trying to do in my articles. I have deliberately chosen the most difficult subjects, like St-Christopher, because they are a common target of modernists. If you look again at the end of the article, you will see that the question posed, whether we should sidetrack St-Christopher because of the savvy scientific age we live in, is answered by a promise to take the reader on an encounter with St-Christopher in my next article. Hopefully I will be able to show that despite the arrogance of rationality, there are still monsters at the edge of the world…

Thank you for your response. I was wondering if the next article would, in some way, answer my question, and it seems it will. I look forward to reading it. Please keep me in your prayers.

A side note on the subject of the dog. It is also relevant to mention that the dog is truly a symbol of periphery and not just one of “outsider”. Here, I mean periphery in the sense of in-between, as you have mentioned, and not merely as alien. First of all, there is the simple fact that the dog is a domesticated animal, and so, it stands in a “gray zone” between the wild beasts and humanity. The dog is not a wild beast, but at the frontier. Also there is the fact that humans train dogs first and foremost as guard-dogs (even as shepherds) and as hunters. These two functions truly give the dog a role that is in-between civilisation and the wilderness.

These things are indeed obvious, but I mention them anyway because such simple things can easily be overlooked, and yet they reveal much about the meaning of symbols.

As usual, you are quite right about this. I have been emphasizing distance, but the dog shows the closeness of the limit, an animality which is potentiality a tool of humanity, so can it be ridden upon by those that have the capacity.