Similar Posts

This post is the first part of a series. Part two: St. Peter on the Right, St. Paul on the Left, Part Three: Authority on the Right, Power on the Left

Anyone interested in iconography has certainly contemplated the wonderful 6thcentury encaustic Sinai icon of Christ. Although most agree it is beautiful, even at the first glance one senses something “off” about the icon: the right and left side of Christ do not match.

This impression is so strong, I have seen some iconographers “correct” the image when attempting to copy it. The explanation most often given is that Christ’s right represents his merciful side, while his left represents his rigorous side.

This may seem far-fetched to some, something as an after the fact desire to explain the discrepancy, but a survey of iconography will show us how pervasive this Left-Right relationship is and how it is a major element in the structure of many icons.

The idea of the right and left of Christ representing the merciful and rigorous comes from the New Testament,

“When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, he will sit on his glorious throne. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate the people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. He will put the sheep on his right and the goats on his left. Then the King will say to those on his right, “Come you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance… Then he will say to those on his left, “Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. …”

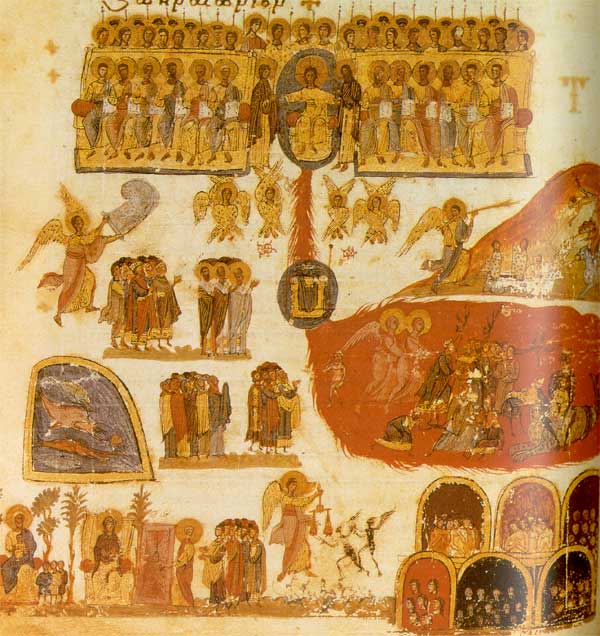

The very image of the Pantocrator is of that “Son of Man in his glory”, being identified with Christ who shall “return again, to judge the living and dead”. Therefore the deisis, the image of Christ in glory flanked by specific saints is already a summary image of the Last Judgement. It comes naturally then that the deisis is always at the summit of the icon of the Last Judgement, where we can see the process of separation in the form of three columns. Christ with certain other “central” elements such as the hetymasia, the balance, the cross and some others form the central pillar splitting the image into a right and left side. What we could call this double effect of Christ can be seen as a “bringing in” and “casting away” but it can also be understood as a “raising” and “lowering” as found in the words uttered by Simeon upon seeing the Christ Child: “Behold, this Child is destined for the fall and rising of many in Israel”.

This composition of three columns, or three pillars is extremely pervasive in iconography and we could hardly exhaust the breadth of its meaning, but regarding rigor an mercy, it also appears boldly in the general interpretation of the cross and the crucifixion. In a troparion of the 9th hour we hear that:

“In the midst of two thieves, Thy Cross was found to be a balance of justice: for the one was borne down into hades by the weight of his blasphemy; the other was raised up from his sins to the knowledge of theology. O Christ God, glory be to Thee.”[1].

In more complete images of the crucifixion, one will find the good thief crucified to Christ’s right and the bad thief on the left. In later images, we might also see an angel and a demon according to a tradition which finds voice in St. Macary the Great:

“When the soul of a man departs out of the body, a great mystery is there accomplished. If it is under the guilt of sins there come bands of devils, and angels of the left hand, and powers of darkness take over that soul, and hold it fast on their side.” [2].

Detail of good and bad thief with angel and demon carrying away their souls, from a 16th century icon in Kiev

And in some traditions, even the Slavic cross, the famous three-barred cross seems to retain this meaning of the left and right. From a Russian iconography handbook we are given the explanation:

“Question: Why is the footboard of the Cross of Christ pointed with the right side up, and the left down, and the head of Christ is also inclined to the right? Answer: Christ makes His right foot light and lifts it above the foot board in order to lighten the sins of the ones who believe in Him. And His left foot He lowers on the foot board in order that those who do not believe in Him should be weighed down and descend into hell. His head is inclined to the right, that He might incline all the heathen to believe and to worship Him.”[3].

There are also certain icons, not necessarily structured according to the three columns, which can in some of their variations manifest these attributes. In some icons of the Anastasis, such as the famous 14th century fresco from the Church of Christ in Chora, we find this separation in three columns. There, all the figures with halos are on the right of Christ with Adam, while none on the left with Eve have halos. Adam is also in white whereas Eve is in red. White and blue are very much related to the right whereas red is related to the left. This link to certain colors is a very deep noetic relationship and it can still be seen as true today, as even our experience of faucets, with the hot/red on our left and blue/cold on our right testifies to how even the modern world, hard as it tries, cannot completely eliminate symbolism.

Although the notion of Christ being rigorous is one that is not popular in our world, it is nonetheless very important as it shows most strongly how Christ in his person unites these two opposites which are born from the very fall of man, which are born from the identification with duality, the knowledge of good and evil. This moving away from the truly Good, the good beyond all possible opposition brought about the appearance of mercy and rigor, though the Father and His Logos remain unchanged by this. And in the icon of 6th century Sinai we find these aspects of duality brought together beautifully “without mixture” into the person of Christ .

This post is the first part of a series. Part two: St. Peter on the Right, St. Paul on the Left, Part Three: Authority on the Right, Power on the Left

Adam and Eve from the Catacombs of Rome. In this type, the tree of Knowledge plays the role of the central column.

Fresco of the sacrifice of Cain and Abel from Vatopedi. Christ accepts the sacrifice of Abel on his right who’s smoke goes straight up, and the smoke from Cain’s sacrifice curves away into his eyes. The straight and the crooked are also related to the right and left hand.

[1] Cited by Saint Jean of Kronstadt in a letter explaining le the meaning of the third bar in the Russian Cross, from, Living Orthodoxy, Vol. IV, No. 3 (May-June 1982), pp. 22-24.

[2] Fifty Spiritual Homilies of St. Macarius the Great , Homily 22 p. 171, Eastern Orthodox Books, Willits, California, 1974

[3] Cited par N. Pokrovsky in a supplement of the “Russian Orthodox American Messenger”, January 1903,

[…] Jan 15th 8:11 amclick to expand…Mercy on The Right. Rigor on The Left https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/mercy-on-the-right-rigor-on-the-left/Tuesday, Jan 15th 8:00 amclick to expand…Building A Habit of Prayer […]

Thank you for this article. I have one addition to make from St. Catherine in the Sinai. Their mosaic over the main alter is of the Transfiguration. Their challenge was to portray Our Lord humanity and his divinity. Jesus is robed in bright white as one might expect. On the mosaic’s right, His hand is white like his garments. On the mosaic’s left, His hand is fleshly. This is one, if not the earliest mosaic/image, to deal with this subject and follows your treatment of the importance of organized iconology.

[…] a bit of western typology. St-Michael with a sword and St-Gabriel with a lily, the symbols of rigor and mercy. St-Michael […]

ORTHODOX WORLD…

http://www.linkurigratuite.info…