Similar Posts

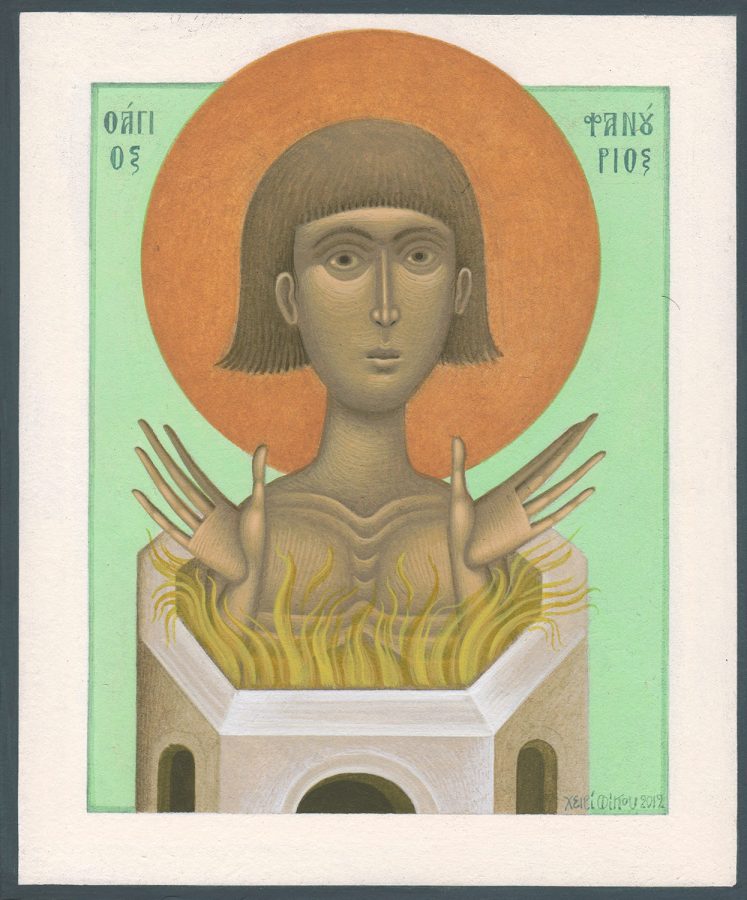

Contemporary Byzantine Painting:

Street Art and the Icon in Convergence

An Interview with Fikos

By Fr. Silouan Justiniano

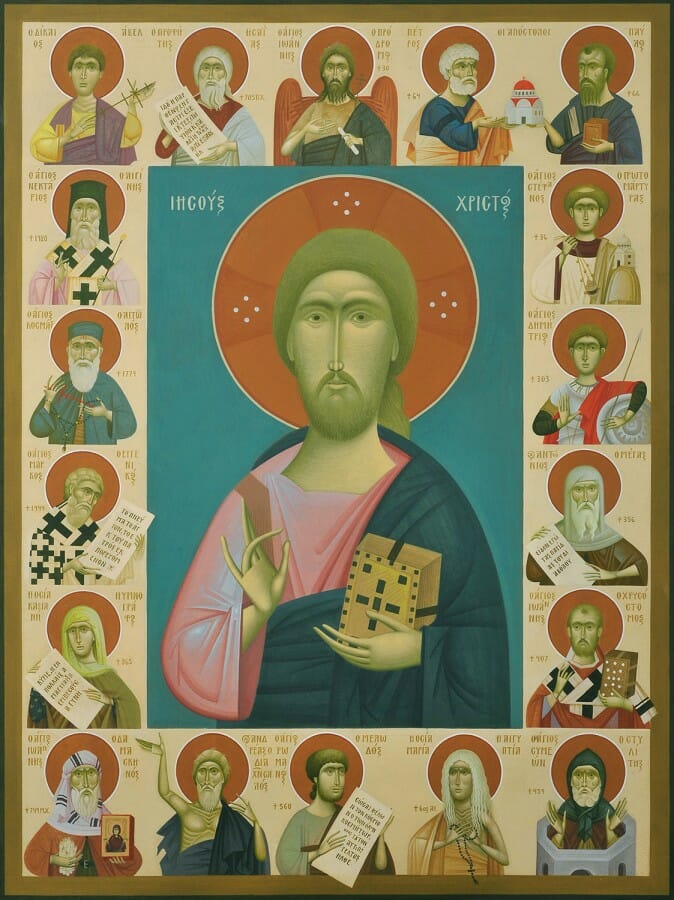

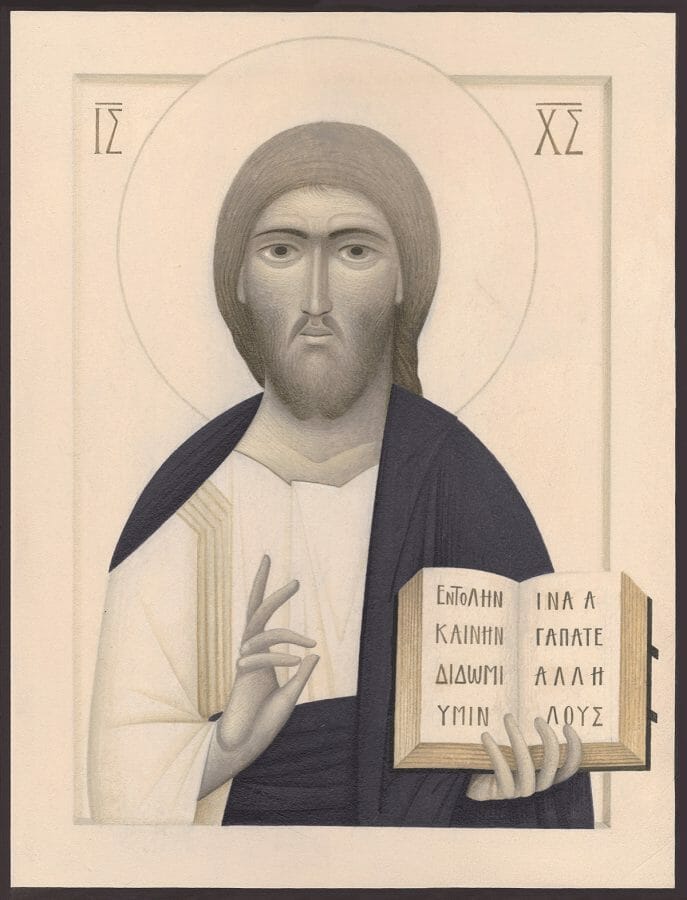

The History of Orthodoxy in Persons, by Fikos, 2012. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood, 80×60 cm.

Graffiti is one of those art forms that seems to have no relationship whatsoever with the liturgical art of the icon. Unlike the icon’s inextricable reliance on Tradition, graffiti appears to embody an anti-traditional and revolutionary attitude, an inner rage born out of frustration against the fumes, dust and disarray of the industrial and desacralized cityscape, the gray concrete jungles we call home. With the kind of illegible “scribbles,” vulgarities and grimy environments generally associated with graffiti we are indeed worlds apart from the peaceful inner sanctum of a Church nave, gloriously decorated with frescoes of heavenly realities. Likewise, is there not a contradiction between the street artist and the pious iconographer? The one humbly avoids popularity in refraining to sign his work, the other seeks it by putting up his “tag” everywhere he can, with marker, brush, roller, sticker or paint can. Most would think of the graffiti artist as nothing but a rebellious youth defacing, vandalizing, and bemiring concrete walls or any empty and clean public space, in defiance of the law, just for the cheap thrill of getting away with it, just because he can. Hardly anything having to do with the prim and proper world of liturgical art.

Unforgiven, by Fikos in collaboration with the calligrapher Simon Silaidis, 2013. Acrylic colors on wall, 4.2×3 m. Sanatorium of Mount Parnitha, Athens.

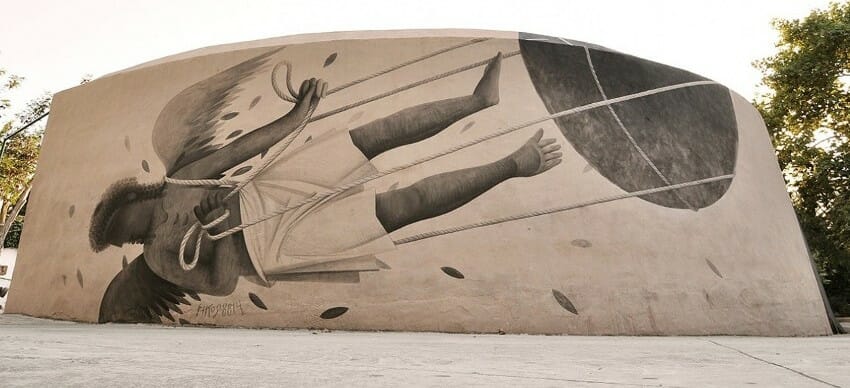

Yes, graffiti can be seen as nothing more than a scream of defiance against the constraining and stifling establishment…Yet not all forms of graffiti consist of vandalism and redundant disfiguring, the futile attempt to fight ugliness with ugliness. There is also, if we take the time to look beyond our preconceptions, in the best of its masterpieces, an attempt to dispel misery, enliven and beautify the dehumanized, mechanistic and dystopic cities we have constructed for ourselves in our frantic pursuit of “progress.” Can graffiti possibly bring us to remembrance of our common humanity, meant to aspire towards a higher life of blessedness? Perhaps… If so even graffiti, or at least some of its more positive strains as found in recent Neo-muralism, can be seen as an attempt to imaginatively transform our bleak post-industrial environments ̶ to offer an alternative vision ̶ by infusing them with images suggestive of a far richer, living and higher reality, imbued with beauty, lyricism, joy, rhythm and hope. So similarities with the icon in fact begin arise…

The Formation of the Demos (municipality) in Athens, by Fikos, 2012. Acrylic colors on wall, 14.5×3.3 m. Sacred Way (Iera Odos), blind side of a warehouse at the Agricultural Department of the University of Athens.

Mural for “Make a Move” Festival, by Fikos, 2013.

Materials: Acrylics on wall, 10×4.5 m

Limerick, Ireland.

Mural for “Bubbledays Festival”, by Fikos, 2014. Acrylics on wall,

12×5.2 m. Linz, Austria. Photo by: Philipp Greindl © flap.at

However that may be, although the icon and graffiti might at first appear to be utterly unrelated, a convergence between them does in fact exist today as an undeniable reality. This is clearly to be seen embodied in the work and person of Fikos, a contemporary artist whose background encompasses both realms of street art and iconography. It goes without saying that we’re not proposing the facile adoption of contemporary graffiti motives to be used within a church ̶ to bring the street into the nave, so to speak. However, given that a convergence is already taking place the question does present itself as to how some of the pictorial aspects of street art can in fact coexist or collaborate with the liturgical art of the icon today and vice versa. So it was only natural that to explore some aspects of this topic we discuss the matter in the form of an interview with Fikos, which I was very glad to conduct recently. In the interview which follows we also touch on some aspects of iconography as a “living tradition” and broach the difficult question of how much meaning we can attribute to style. Fikos’ views in some respects give us a slightly different angle, a counterpoint as it were, to the ongoing and diverse discussion about style we’ve had in recent articles, such as “The Pictorial Metaphysics of the Icon,” Aidan Hart’s, “Today and Tomorrow: Principles in the Training of Future Iconographers,” and Jonathan Pageau’s, “The Robot, the Mutant and the Artist.”

Born in 1987 in Athens, where he still lives, Fikos started from a very early age to paint and draw all that he saw around him, including comic book strips, landscapes and icons. This eventually led, at the early age of 13, to his apprenticeship under the renowned iconographer George Kordis. While collaborating with Kordis on his Church commissions for the next 5 years Fikos also honed what would become the main stylistic features of his work. To this day he continues the pictorial development of his work by painting murals in public places. However, he doesn’t consider his painting to be “just another artist’s ‘self-expression’, but a social event a true “creation” (‘demiurgia’ = demos ‘citizens’ + ergon ‘work’) – a work for the citizens-society.” [i] Thus in this sense Fikos’ understanding of “street art” also parallels the liturgical function of the icon ̶ a work by and for the people, the society of the faithful.

The Prophet Elijah Sleeping, by Fikos, 2008. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper on wood, 47×32 cm.

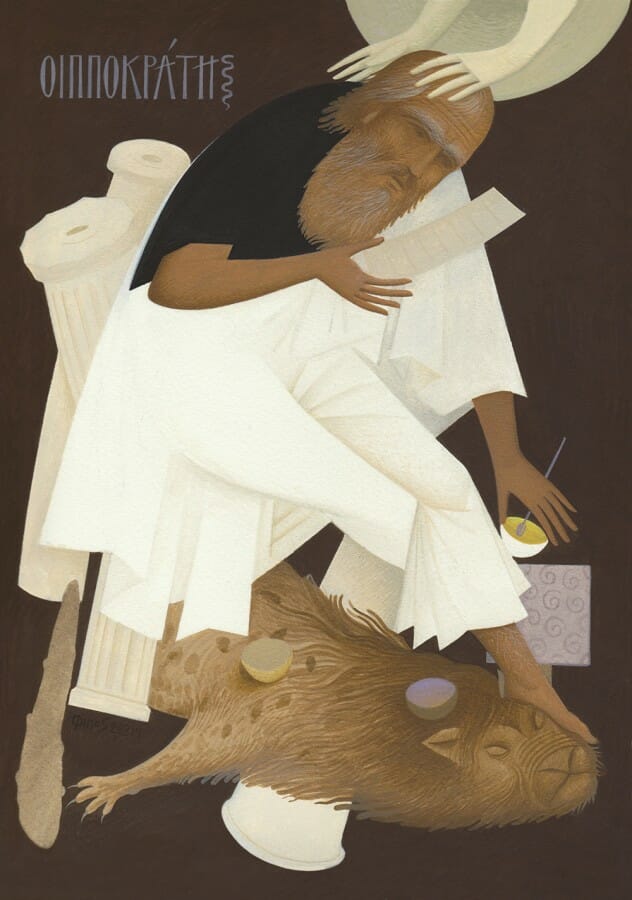

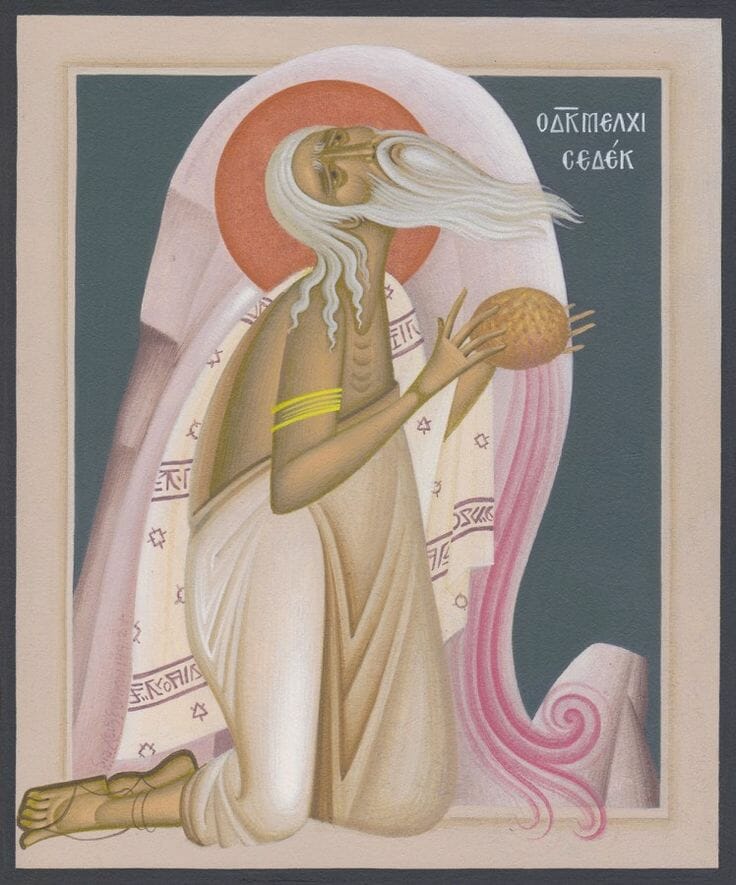

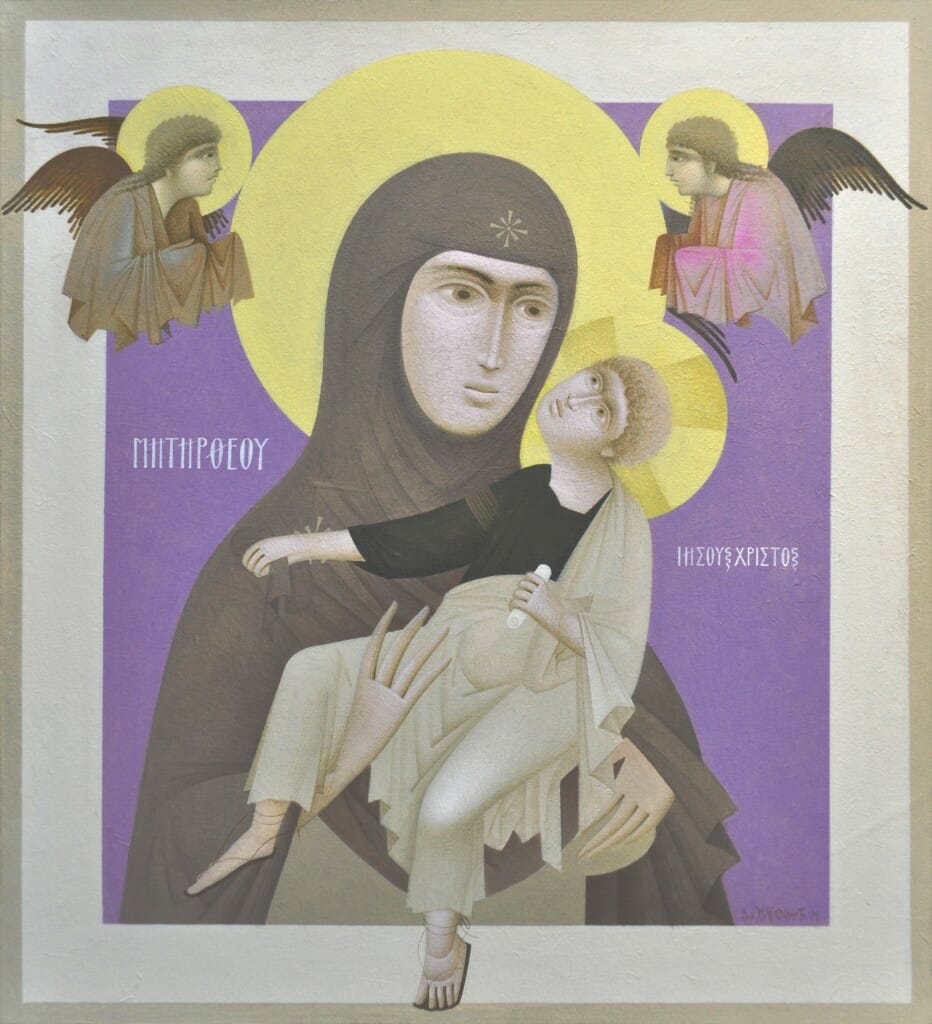

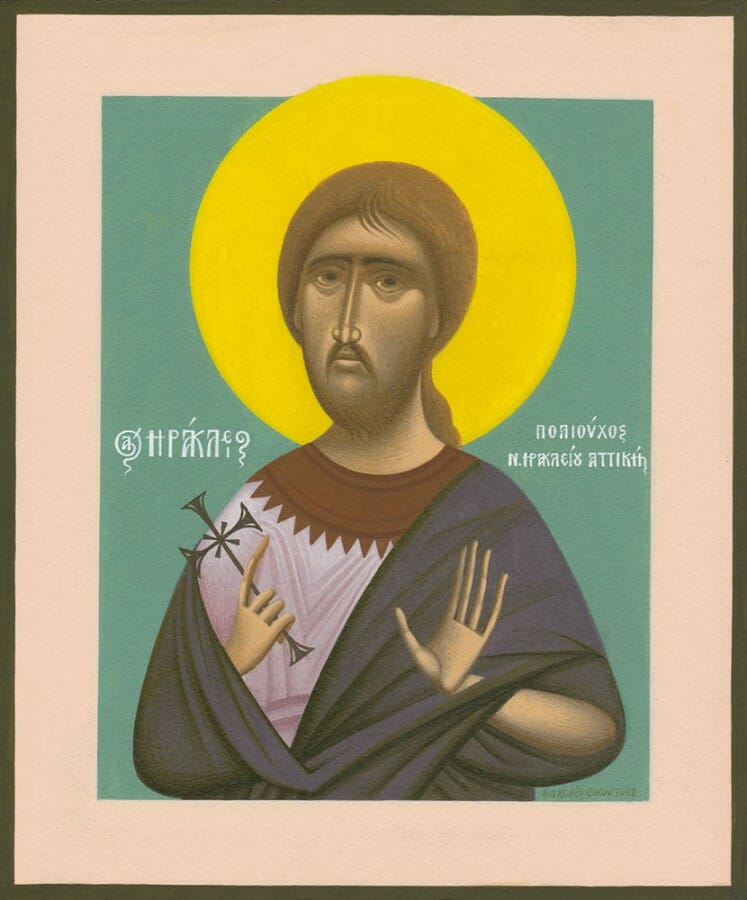

The value of Fikos’ works is exceptional, since it’s arguably the first time that the monumental byzantine technique meets a contemporary movement such as street art. This has led him to refer to his work as “contemporary byzantine painting.” The themes of his murals emanate both from the Orthodox Christian Tradition and ancient Greek mythology, and are conceptually related and compositionally grounded to the places where they are executed. Moreover, his themes relate to the universal concerns and experiences of our common human condition and therefore tend to be imbued with symbolic, spiritual and didactic significance.

Fikos’ has received international acclaim among the street art community. Besides Greece, his work has been exhibited in France, Bulgaria, England, Ireland, Ukraine, Austria, Lithuania, Switzerland, Norway and Mexico; in exhibitions and museums, television and radio and in private and public places. As he puts it his “vision is the popularization and recognition of contemporary Greek painting at an international level, not as a nostalgic accomplishment of the past, but as a contemporary universal event.”[ii] In his iconography we find the old and the new, the timeless and the contingent, the liturgical and non-liturgical, converging as an unexpected and unique example of living Tradition.

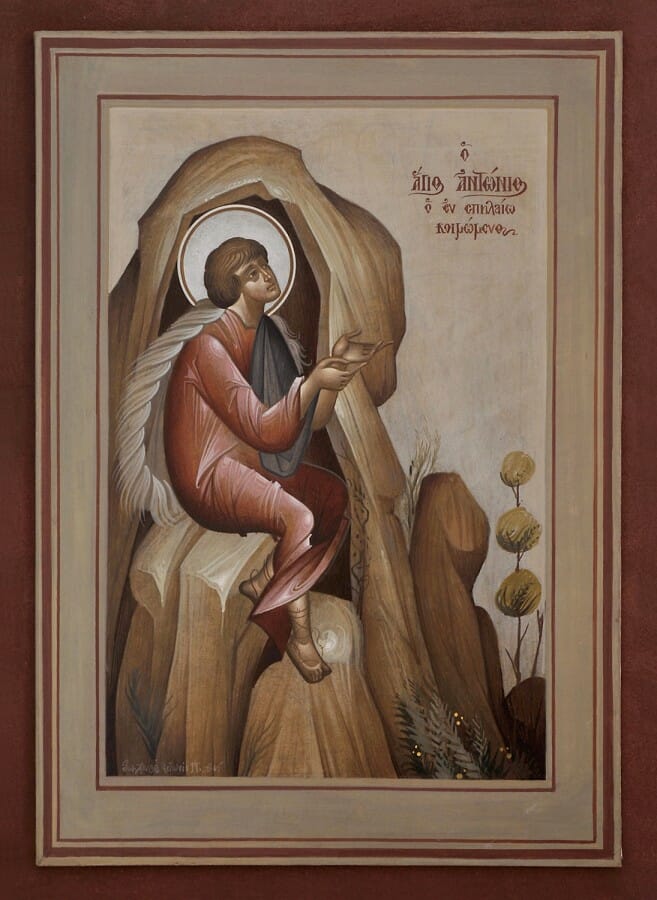

St. Anthony (One of the Seven Youths of Ephesus), 2008.

Materials: Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood, 43×31 cm.

*****

Fr. Silouan: Can you please tell us about your formative years as a painter, the kind of training you received, and the kind of artistic currents that played a major influence in your development at the time? How did you first start painting icons?

Fikos: Since I was very little (6-7 years old) I painted DC and Marvel Heroes and other things from my imagination. Then, at the age of 10, I won a competition of the Sunday school I was attending, with – what else? – an icon. I think that was the spark which started the fire of my love for icons. In the following years I kept painting icons with colored pencils. At that time I was also making wax icons, prayer ropes and embroidery. I was fascinated by handiworks. A few years later, at the age of 13, I started my studies on Byzantine Painting in “Eikonourgia”, an Association for The Research and Study of Orthodox Painting, under the guidance of George Kordis.

The Prophet David, by Fikos, 2007. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood,Dimensions: 45×45 cm.

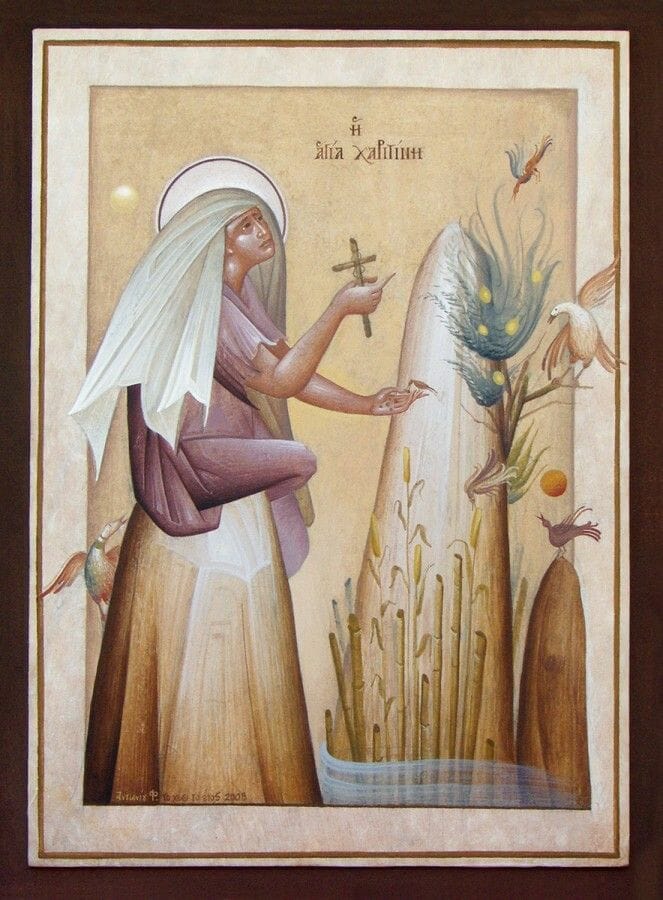

St. Charitine,Dimensions, by Fikos, 2008. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood, 43 ×31 cm.

Fr. Silouan: You’re internationally renowned as a muralist exemplary of the street art movement that has developed in Athens. My impression is that a lot of people still think of street art or graffiti as a form of vandalism. This is still the case to some extent, yet the graffiti movement has come a long way since Taki 183 first started tagging up NY City in 1969. If in the 80’s graffiti formed an inextricable part of the emergent Hip-Hop scene, it seems to have expanded far beyond that limited context. How would you describe the kind of street art that you do and how does it fit into the Athens graffiti scene?

Fikos: I think there are three phases in graffiti’s evolution. The first one is Graffiti. The second one is Street Art, and the third is what some people have called Neo-muralism. This is the mural movement we seen arising in the last 5 years and the one I believe describes better the kind of art I do. Muralism is actually more related to fine arts than graffiti. Most of the times it’s just large scale painting.

As for the Athenian graffiti scene, personally, I mostly work abroad so my presence in Athens is not that strong anymore. I stopped putting a lot of energy the moment I realized that no mural of mine stays alive without being vandalized after no more than a few weeks. Athens is a badly graffiti-damaged city. Tags are everywhere. From public and private spaces to churches, and from trucks to shops’ glass partitions. What Athens needs now is more clean walls and some nice large scale murals with positive images and messages. I can’t do the first so I will try the second.

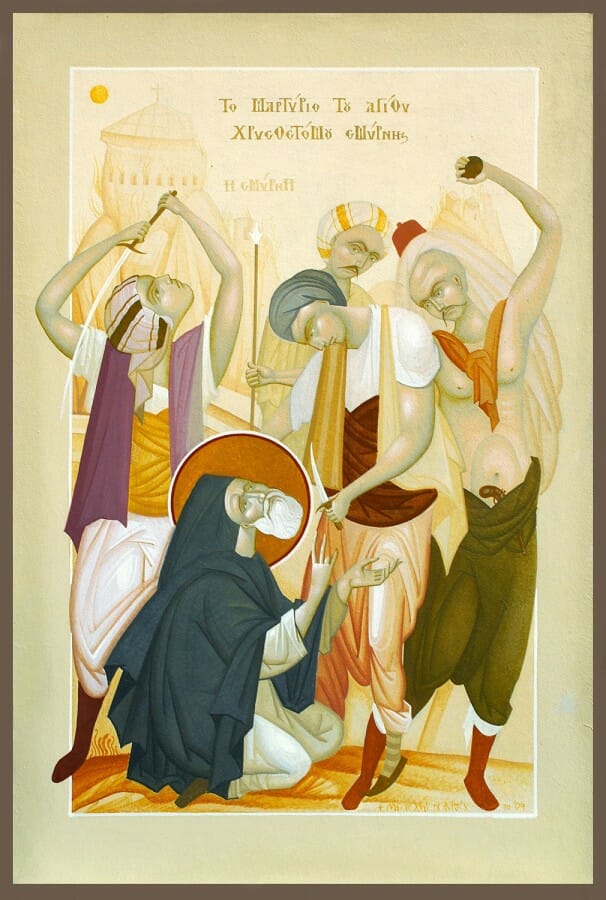

The Martyrdom of St Chrysostom of Smyrna, by Fikos, 2010. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood, 48×33 cm.

Fr. Silouan: It goes without saying that graffiti touches on common preconceptions surrounding “high” vs. “low” art, or “fine” vs. “popular” art forms. Roughly speaking, for some the first is thought of as providing a venue for a kind of refined “aesthetic contemplation,” whereas the latter is seen as unsophisticated entertainment. Or, from another angle, the virtue of the first is seen in its utter uselessness, while the second suffers from servitude to function. In any case, what are your thoughts on these presumed dichotomies in the realm of art and how do you see them as affecting your process as a muralist and iconographer?

Fikos: As an artist you shouldn’t let these dichotomies penetrate into your art and way of thinking. Moreover, nothing is black and white in life. I prefer focusing on what I do while being open to everything around me, even if it’s negatively judged by me. There is always and everywhere something good to take if you see beyond the surface. Unfortunately, people have the ability to instinctively reject anything new. I’ve been taught that from my years of experience within the sphere of the Church and the liturgical arts. People are so much afraid of changes in the tradition that they end up making the Church a museum of ecclesiastical arts. Painting from the 14th century, wooden iconostasis from the 18th century, huge chandeliers from previous centuries with fake electric candles, etc.

This thing is not tradition. It’s history. History is a very good thing and you can learn a lot from that but it belongs to the past. It’s a dead thing. It doesn’t fit to the house of God. Of course, I am not saying that changing the situation is that simple. When you do art for a group of people you have to be very careful. Wanted or not, you interact with people’s emotions. In this, Street Art is very familiar with liturgical arts. The only difference is that the Church has an experience of 2000 years, so they have already settle about what works and what doesn’t. Muralism is quite a new form of art and it’s totally normal for it to be contested, or for it to have a lot of oppositional criticisms. Let’s give it the time it needs while everyone from his side does the best he can.

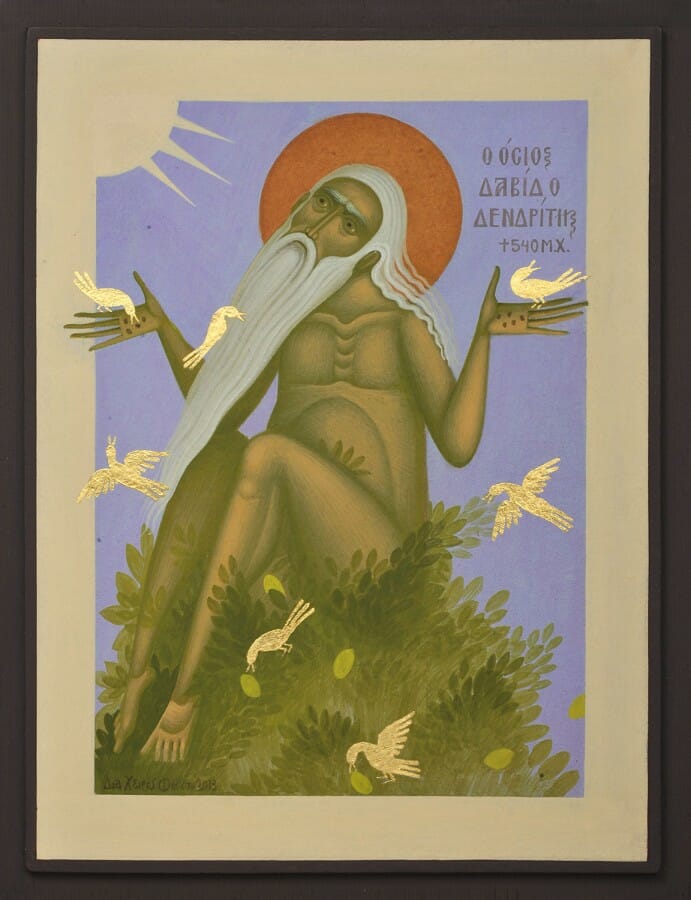

St. David the Tree-Dweller of Thessaloniki, 2013. Egg tempera and gold leaves on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood, 30×23 cm.

Fr. Silouan: How about the “creative act”, what does true “creation” mean to you? Do you see your work as a form of “self-expression”?

Fikos: Creation is a very interesting compound word in Greek. “Demiurgia” consists of the words demos (society, also today municipality) + ergon (work, also an artwork), having the meaning of a work for the citizens and the society; since in the ancient Greek civilization there was no such term or concept as the individual cut off from society.

From my point of view, true creation occurs when the work expresses the creator and at the same time the society to which it refers. I firmly believe that the balance between the two is the secret ingredient missing from the art of our time, since the work of most contemporary artists is the result of “self-expression” which completely disregards the viewer or, in other cases, simply a lifeless repetition of older patterns where freshness and artist’s identity are absent ̶ phenomena which never existed in the history of art as strongly as today.

Fr. Silouan: When it comes to icon painting, you had the privilege of spending 5 years with George Kordis as an assistant, painting murals in Orthodox churches. It is clear that this experience has shaped some aspects of your work, nevertheless, there is no question that your own stylistic voice takes precedence. What aspects of Kordis’ methodology and ideas do you see as having had shaped your overall approach to the icon and street art? What do you think have been the key factors in you process allowing you to maintain an independent voice?

Fikos: When you want to learn the alphabet and the syntax of the Byzantine painting language, with a view to learn how to compose your own “sentences”, Kordis is the person who can teach you. Thank God, I had the “luck” (I don’t believe in luck) to meet him and follow his teaching. However, color, use of light and axis, the necessary contrast in large scale murals, and other visual issues, wasn’t the most important part of my apprenticeship next to this great master. The key factor was his way of thinking, from whom I got inspired. The insight, the ability of reading behind the letters, the industriousness, the philosophical mind, meaning the situation where you creatively question current knowledge in order to find the “truth”. If you combine this teaching with my young age and a little talent I think it’s impossible to have a conventional and trite result.

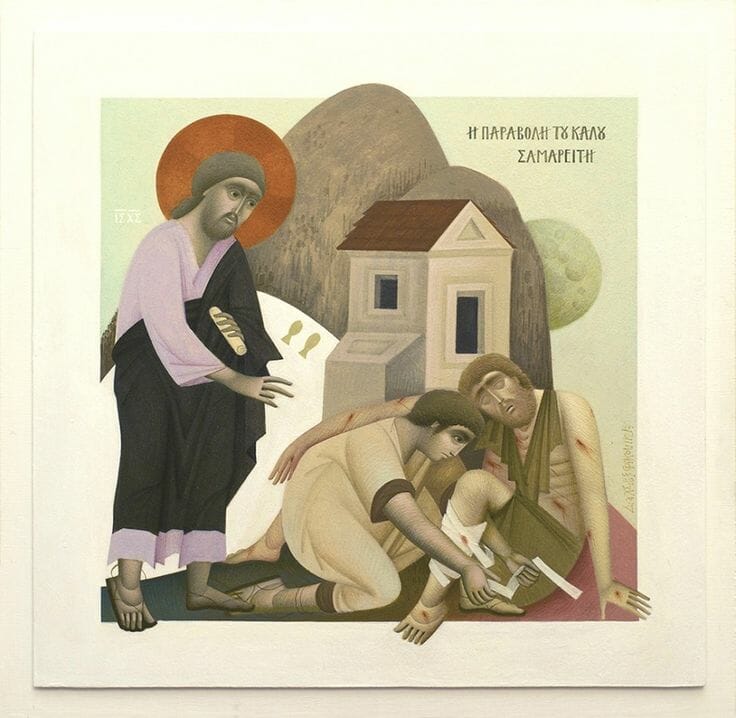

Parable of the good Samaritan, 2013. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood, 33×33 cm.

“Look at the birds of the air…”, by Fikos, 2010. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper on wood,Dimensions: 43×33 cm.

Fr. Silouan: One of the facets of your approach that I find particularly refreshing is how you manage to move from icon painting, to street art, to gallery art, and back to the icon again, in a seamless manner. Church Tradition informs your non-liturgical art, and this in turn informs aspects of your iconography. Yet, in this convergence and cross fertilization of disparate artistic spheres there appears no trace of irreverence, cynicism or irony, the default setting of most contemporary art. All of this gives rise to what you have called “contemporary Byzantine painting”. What do you mean by this concept and how do you understand the role of Tradition when it comes to iconography? How do we surmount the misconception that traditional icon painting means slavish copying, while not falling into the opposite extreme of innovation for its own sake?

Fikos: Over the years I had to find a term that describes best what I do. So I came up with “Contemporary Byzantine Painting”. The term is conventional as it is obvious that something cannot be Byzantine and contemporary at the same time. By “Byzantine” I mean the principles that characterize the art of Byzantium. When these principles are combined with an external shape (style) which expresses the era in which is being created, then Contemporary Byzantine Painting is born. This connection should be meaningful and functional, not superficial. Copying a Byzantine icon and replacing blue with red does not make you “contemporary”. Each element of this kind of painting, from the pleating of a garment to the entire composition, the light, the volume etc. should follow a unique concept.

The truth is that “tradition” is a huge chapter. This is because it has a very wide range of interpretations. For some it’s about rules and restrictions, for others it’s about freedom and even a good tool. Everyone will agree that tools exist to serve us, right? Yet, some people believe that we should serve this tool called “tradition”. Because, at the end, what is tradition if not a tool? A good assistant? Tradition is the whole experience of thousands of people over thousands of years. Nothing more, nothing less. None of these dead people can forbid anyone from doing anything. What it can do though, is to show what it has tested, what works and what doesn’t, under particular circumstances. If you work in other conditions, tradition automatically MUST be questioned. I believe that it is understandable that I do not speak about “questioning for the sakes of questioning”, but for functionality as criteria.

Photis Kontoglou was the regenerator of Byzantine painting in Greece after 4 centuries of Ottoman rule, where the generation of Byzantine art was interrupted. With his painting he showed us clearly in himself that it’s impossible ̶ for a man who has lived in the 20th century, studied Modernism in Paris, painted on canvas under electric light and used acrylic paints ̶ to paint the same way as a 13th century painter, who never left the boundaries of Byzantium, never saw a photograph, and always painted with natural or candle light on wet plaster in specific architectural forms of Orthodox churches. In other words, the art of the Byzantine painter is an art of another culture.

This is the proof that Byzantine painting can be neither servile reproduction nor a pretentious effort for originality – it’s the tradition itself. The painters of Byzantium neither copied nor were trying to stand out. They wrote the word “life” each one of them in their own handwriting.

Fr. Silouan: Your work draws on various sources such as archaic Greek art, Cycladic and Sumerian art, the Byzantine icon, modern art and street art. All of these might at first appear to be pictorially irreconcilable but somehow you have managed to find, in my opinion, a harmonious synthesis. Can you please elaborate on the main pictorial principles that you feel tie all of these forms of art together?

Fikos: Tradition is the link, the interface that brings all other materials together. It’s the body that accepts all clothing and jewelry with which it will be adorned. Since you have found the particular tradition (any tradition) that you will work on, the quest begins. How are you going to evolve it? What are you keeping and what are you discarding? What expresses your era the most? What do you like and what expresses yourself? What kind of materials do you use and why? A quest of questions like these never ends.

I often compare myself to a gold digger, since, like him, I have devoted my life to exploring. I am a passionate world traveler, I read books on a daily basis, and I am also an amateur photographer. Not a single day passes without being updated on the global art scene. I seek among thousands of images that are “sifted” by my eyes in order to find an element which could be functionally “grafted” with this painting style – a small fragment of gold which I will be able to add on the crown of the long history of Byzantine Art. That little fragment is plenteous.

The Birth of Wine, 2015. This work was done for Oenorama, the largest and most prestigious wine fair in Greece and hosts more than 130 wineries every year since 1994. The artwork was painted on an old barrel of a famous winery and illustrates wine’s process from the planting of the winery to the results wine induces.

Mural for the Bukruk Festival, by Fikos, 2016. Acrylics on wall, 23×13 m. Sovann Macha-Bangok, Thailand.

Fr. Silouan: It seems to me that the main subject of your non-liturgical work is the human condition, man himself, as he confronts the mystery of his existence. At times the compositions draw on religious and mythological themes, at others the narrative becomes an ambiguous dreamscape, then a touch of the tragic comes in, mingled with a bit of eros. Although there is a lesson to be learned from the story, the work doesn’t spell everything out for the viewer, it’s not offered up for easy or passive consumption, we have to engage with it and finish the creative process through interpretation. So how have you managed to imbue your non-liturgical art with a sense of the timeless? How do you tap into and arrive at these universal themes?

Fikos: As rightly noticed, I focus a lot on the human being and its experiences. Humans have an innate selfishness, so they think that everything that is associated with them is special: their selves, their relationships, their experiences, their era. The truth is that we are all special individuals, but the situations we experience are the same for the whole human race since thousands of years. Pain, joy, sorrow, redemption, faith, love… This is life. Over the years I noticed that this kind of wisdom is hidden in every nation’s mythology and folk tradition. Purified and with no ephemeral elements, such as depicting extreme emotions, temporality, gravity, light source, etc. Mythology and tradition represent the essence of facts detached from time in an educative way.

St. Pantaleimon Blessing Youth, by Fikos, 2010. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood, 35×35 cm.

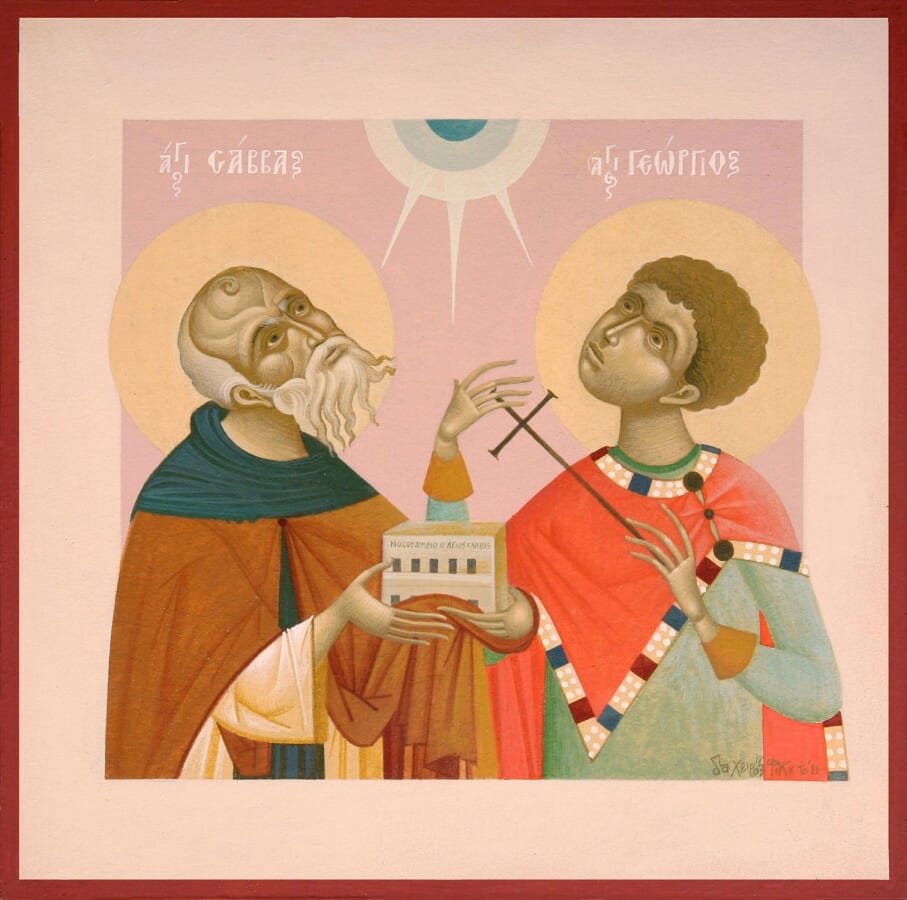

St. Savvas and St. George, by Fikos, 2011. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood, 25×25 cm.

Fr. Silouan: So would you say that your non-liturgical work is an example of how contemporary art has the potential of introducing intimations of the sacred within a desacralized cultural sphere? And would you say that this is so because it is being fed and has an inextricable link to the sacred art of the icon?

Fikos: It is true that a lot of people see a religious solemnity in my painting but I ‘m not sure if this actually exists. You see, in our era, Byzantine art is identified in the common consciousness with something so called “spiritual”. Unfortunately, we forget that it is simply a visual language, one of many around the world. A medium. I believe that any reasonable person agrees that judging a medium is not right. You cannot say “television is bad”. It’s not correct. You can watch the most violent and ugly images on TV and at the same time watch a nice documentary or the Sunday Service. It’s just a medium. Ancient people had solved such issues ̶ that is why they painted their gods in the same way they painted the Pompeii whorehouses. It sounds weird although it makes perfect sense. Has anyone ever thought of praising the Lord in a different language than when cursing or arguing? Or how would it look like if someone said that the only language we can praise God in is Hebrew, because this is the language that Jesus Christ talked?

With these examples I would like to point out that Byzantine art is simply a language. Its only particularity is that, for various reasons, it has served and was evolved almost exclusively in Church. So, it formed and based its “vocabulary” and thematic on its function. Its form, then, makes sense only if it refers to Christ. Using this style unchanged and talking about other matters is hollow, meaningless. You must change its elements and adapt them to new needs. Consequently, the only “sacred” thing that survives in this style is the images perceived by the people. It’s not something real and measurable. To conclude with transferring a sacred idea in a desacralized cultural sphere could be a seemingly easy answer. But what if, with this “sacred” painting violent and sick images are being represented? Is this kind of insult addressed directly to the mother of this painting style, the Church? Thus the thematic is very important and the painting style by itself says absolutely nothing.

Salvation, by Fikos in collaboration with the calligrapher Simon Silaidis, 2013. Acrylics on wall. Abandoned textile factory, Ν. Philadelphia, Athens.

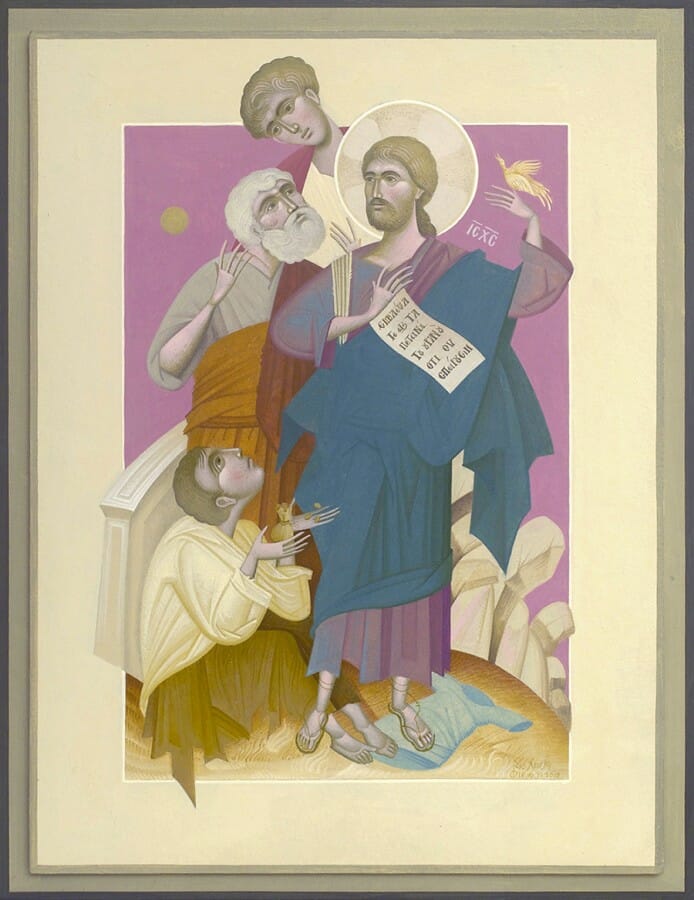

Jesus Christ, Dimensions, by Fikos, 2016. Egg tempera on handmade Japanese paper glued to wood, : 30×23 cm.

Fr. Silouan: Can you please tell us some background about your most recent project at Kiev, which actually ends up being, as you put it, “the largest mural in the history of Greek art”? How did you deal with keeping the proportions resolved as you worked in such a large scale? Can you also elaborate about the symbolic significance of the theme you’ve chosen for the composition?

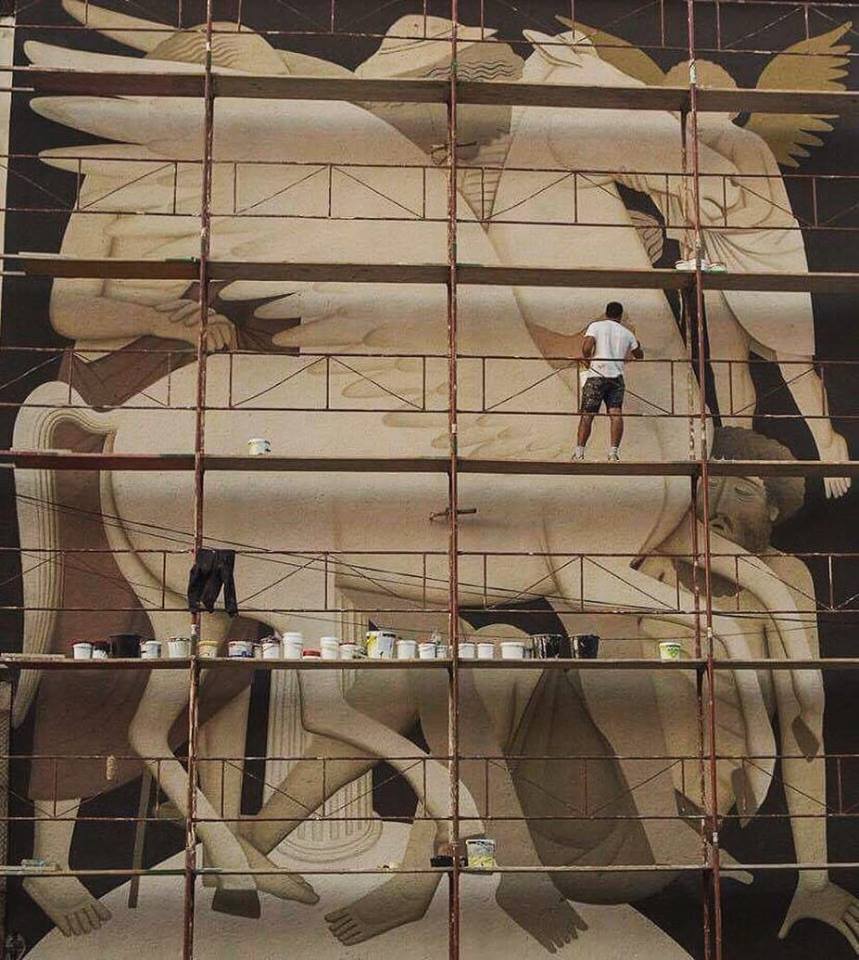

Fikos: This mural is titled “Earth and Sky” and was created after being invited to participate in the Mural Social Club, a project organized by the Sky Art Foundation. Byzantine murals were not painted in a large scale, so considering the fact that Saint Sophia in Constantinople (Istanbul) with a total height of 55 meters is one of the largest temples of Christian faith, then “Earth and Sky”, of 46 meters height, is the largest mural in the history of Greek-Byzantine art.

Fikos Antonios in Kiev for Mural Social Club Festival/NGO Sky Art Foundation. (photo © Maksim Belousov)

The mural’s theme came out as a result of the painting process. The inspiration I got from Mucha, whom I’ve been studying lately, and his graceful female figures, combined with the long and narrow shape of the wall led me to Earth’s posture, which later got enriched with other elements. It took me 13 days to complete the artwork.

As for the procedure, every artwork is unique. I prefer working directly on the wall and most of the times not based on sketches, but when we talk about these large dimensions it’s quite difficult to do that, especially when you have to work with a lift, where you are literally stuck on the wall, therefore you have no sense of what you’re doing. The most common solution is the one of the grid. There are many artists of course who use projectors, but this technique doesn’t attract me. The truth is that even with the use of the grid, the difficulty is still quite big, especially in my painting where the quality of the line is the dominant component. No measurement can help you a 100%. Experience and perception are required.

Fr. Silouan: Thank you, Fikos, for your thoughtful responses and for taking the time to do this interview. Your work is very inspiring and challenging in many levels. I’m sure it will stimulate much discussion among iconographers that have not yet been exposed to it. It reminds us that icon painting liberates rather than stifles creativity and of how virtually inexhaustible are the pictorial possibilities within its living Tradition. Thank you.

*For further information and more samples of his work see Fikos’ website: www.fikos.gr. Notes: [i] http://fikos.gr/fikos/?lang=en [ii] Ibid.

What beautiful pictures. Thanks for sharing.

Meaningful interview, great artist!

[…] wonderful article in the Orthodox Arts Journal, “Contemporary Byzantine Painting: Street Art and the Icon in Convergence,” introduces the reader to the Greek artist, Fikos. Fikos started painting as a child— comic book […]