Similar Posts

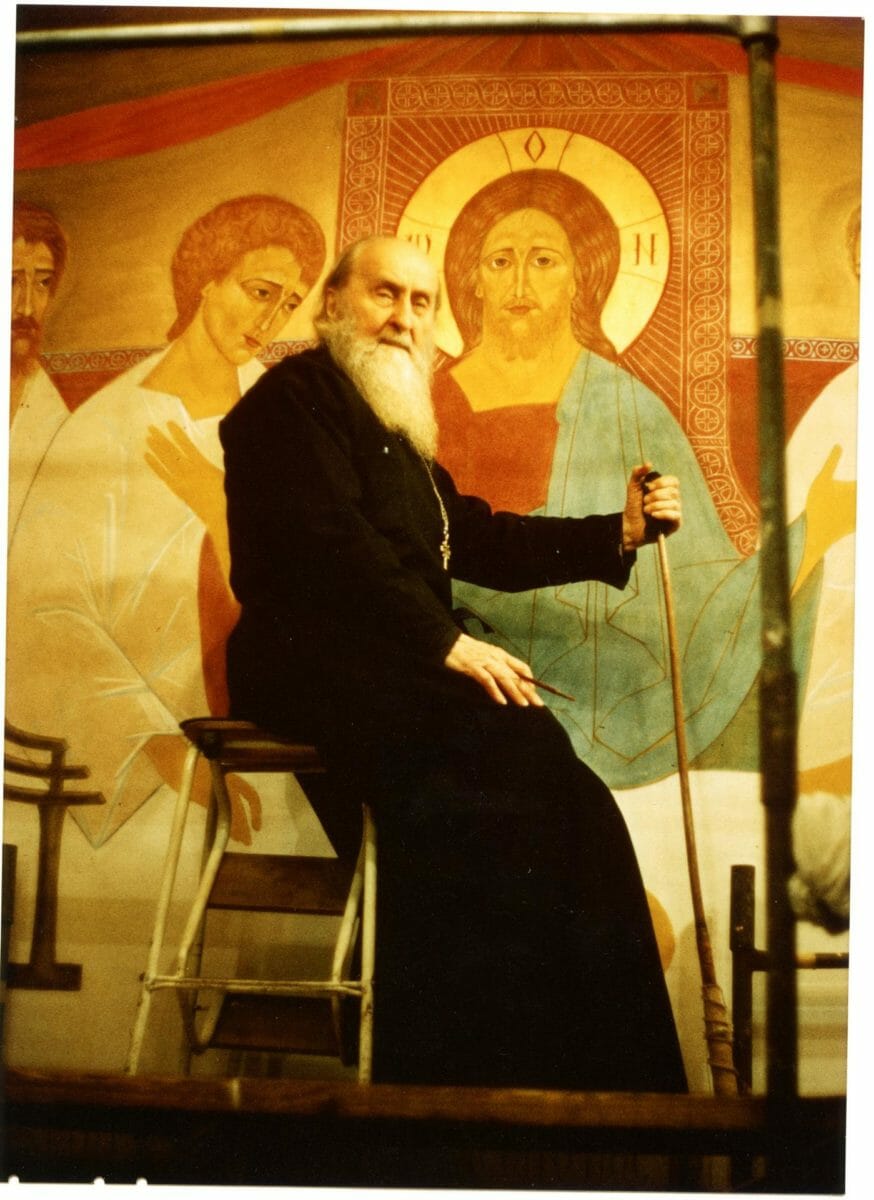

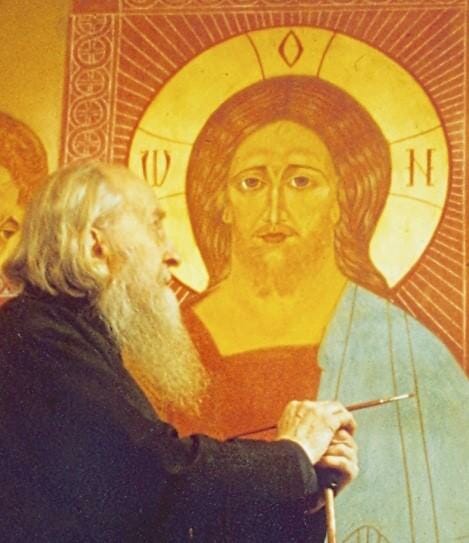

Archimandrite Sophrony, painting Christ at the Last Supper, early 1980s, the Monastery of St John the Baptist, Refectory.[1] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Archimandrite Sophrony, painting Christ at the Last Supper, early 1980s, the Monastery of St John the Baptist, Refectory.[1] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Editorial note: This is the second part of a series on the artistic path and iconographic legacy of Saint Sophrony (Sakharov) as seen through a collection of monographs by Sister Gabriela, a member of his monastic community in Essex, England. Since the publication of the first part of this series, Father Sophrony was canonised by the Holy and Great Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, receiving the title Saint Sophrony the Athonite. Because of his extensive work as an iconographer and liturgical artist, his canonisation is particularly significant for iconographers, liturgical artists and lovers of the liturgical environment. The previous summary of Seeking Perfection in the World of Art: The Artistic Path of Father Sophrony can be found here.

************

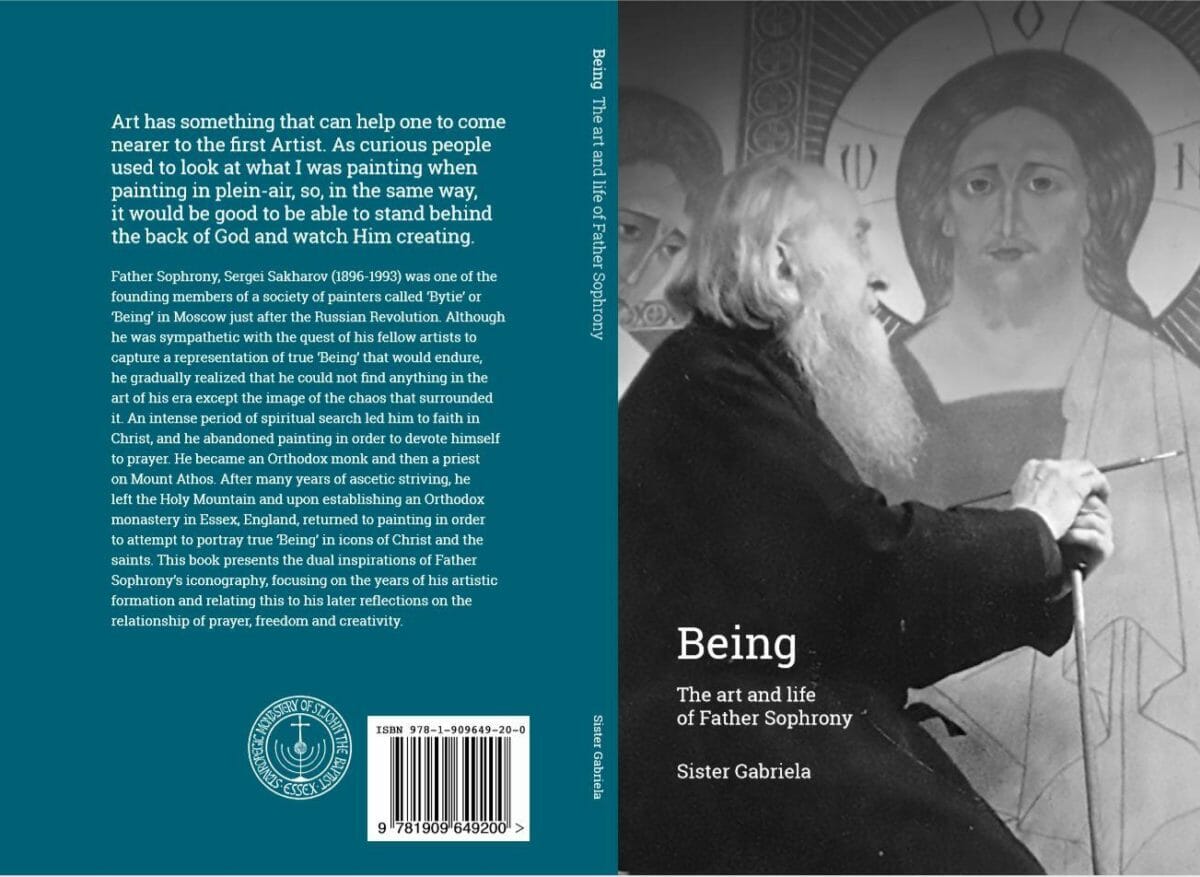

Continuing the exploration of the exceptional iconographic work of Saint Sophrony the Athonite (1896-1993) begun in the summary of Seeking Perfection in the World of Art: The Artistic Path of Father Sophrony, we now come to the second monograph in this unique series by Sister Gabriela, which is entitled ‘Being’: The Art and Life of Father Sophrony (2016)[2].

Book Cover of one of the English editions of ‘Being’. Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Introduction:

During the last century, Saint Sophrony the Athonite emerged as a leading ascetic and spiritual father, hesychast, and theologian par excellence of the hypostatic principle and the Uncreated Light. Uniquely, he simultaneously strove to express both his immense theological and personal spiritual experience through his iconographic practice at the various environments he meticulously created, especially those throughout the monastery he founded in England in 1959.

Sister Gabriela is a member of Saint Sophrony’s monastic community at the Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist in Essex, England, and is also an accomplished iconographer who, after initially studying with Leonid Ouspensky in Paris, made her iconographic apprenticeship with Saint Sophrony. As well as containing extensive new research on the saint’s life, much of the book is based on her personal notes made over 10 years throughout which she assisted him on many iconographic projects.

In ‘Being’ we find a penetrating and thought-provoking excavation and analysis of many of the main and nascent themes found in Seeking Perfection (the first book of the series), as well as extensive new material much of which is unknown and has never previously been published. This further elucidation of Saint Sophrony’s work was also an opportunity to publish many of his additional thoughts and insights on the subject of Orthodox icon painting, whilst simultaneously looking into his involvement as one of the founding members of the group ‘Bytie’ (being) in early 1920s Moscow. Sister Gabriela chose to make a special study of this particular strand of his life as his early involvement with the group so exemplified and mirrored what was to become the saint’s lifelong search for the meaning of Being.

Sister Gabriela writes that “The quest for knowledge of Being runs like a thread throughout Father Sophrony’s life. At times it gets fragile, in danger of snapping, at other times it wears tenuously thin; but in spite of all the tribulations, it is not broken and through tireless perseverance it ends up not just as strong as a rope, but ultimately, a lifeline.”[3]

The Search for Being – beginnings:

The young Sergei Sakharov’s family residence in Moscow, taken in 2013.[4]

The examination of this unbroken thread begins during Father Sophrony’s childhood in Moscow and traces his spiritual and artistic development. It is evident that from his youngest years he was preoccupied with spiritual questions and possessed spiritual and artistic gifts. She writes that Sergei Simeonovich Sakharov (1896-1993), the future Saint Sophrony, was “from early childhood preoccupied with the question of eternity”[5]. He would often attend church services with his nanny and spent many hours sitting at her feet praying. In his writings he recalls coming out from the Church as a child and seeing Moscow “bathed in an otherworldly golden light while at the same time feeling an ineffable joy and peace.”[6] He often had such experiences but it was not until much later in life that he understood the gift of these manifestations of light, and wrote of it:

“There were occasions when coming out of church I would see the city, then the whole world for me, lit by two kinds of light. Sunlight could not eclipse the presence of another Light. To think of it brings back the feeling of quiet happiness that filled my soul at the time. I have forgotten almost all that happened in that period of my life but the light I have not forgotten.”[7]

His father, Simeon Sakharov, “…arranged for his children to attend the best schools, providing a solid education, rich in Russian literature and culture…where he would have studied sacred history and elements of Christian doctrine, Russian and European literature, both classical languages and French, secular history, calligraphy and a number of other disciplines…”[8] Sergei particularly loved to draw and from his youngest years was often to be found sitting under the hall table drawing.

Artistic training:

Sergei desired to become a painter, for which it was necessary to study at the Moscow Institute of Painting. In preparation for the entrance exam it is thought that “…the studio he most probably attended was that of Fedor Rerberg, which provided a sound, classical foundation in all the traditional techniques of art. The atelier of Viktor Vasnetsov was just a block away from the family home and may well have been another place that Sergei frequented. He held this painter in deep respect, regarding him as a patriarch among the painters.”[9]

Fedor Ivanovich Rerberg (1865-1938), A Church in Sunlight, 1903, oil on canvas.[10]

Viktor Vasnetsov, Rejoice in the Lord, O ye Righteous, panel 2 (centre) of the triptych, 1896, watercolour, gouache, ink, bronze and paper on canvas.[11] State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Study for a wall painting for the Vladimir Cathedral in Kiev.

Existential awakening:

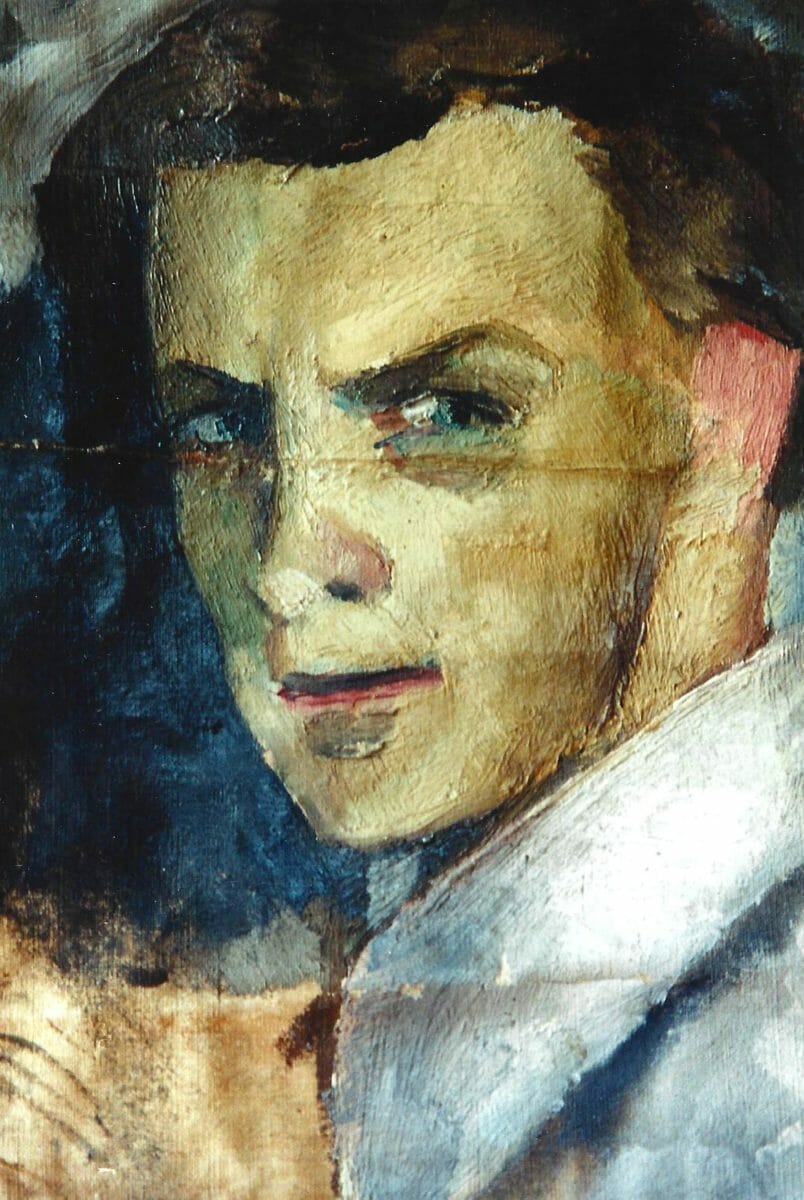

Sergei Simeonovich Sakharov, taken in 1918.[12]

Sergei had been born in 1896, a time of peace towards the end of the reign of Tsar Nicholas II, in the final years of the Russian empire. However, from the age of eight his life was overshadowed by tragic, cataclysmic events: the war with Japan (1904), the first Revolution (1905), the death of his older brother (last quarter of 1909-10), the First World War (from 1914), the Revolution and Bolshevik coup d’état (in 1917), followed by the Civil war. Of this he tells us:

“I was still a young man when the tragedy of historical events far outdid anything that I had read in books. (I refer to the outbreak of the First World War, soon to be followed by the Revolution in Russia.) My youthful hopes and dreams collapsed.”[13]

The catastrophic events “strengthened Sergei’s existential questions: why was he born and what was the purpose of life if it was all to end in death and eternal oblivion. These questions tormented him to a degree that he felt himself to be on the brink of insanity. He did not reveal his inner turmoil to anyone and outwardly continued to live as any other young man, often laughing and joking, yet, the question kept burning within him. Because of his inner struggle, he did not get too deeply involved with other young people and searched for a solution in his art.”[14]

His search centred on the question of death and the concept of eternal oblivion, or non-being. “I contemplated death not only in the body, in death’s terrestrial forms, but in eternity”[15]

In this state of turmoil he continued to pray and read the gospels, “until one day, at the age of 17, when walking down a street in Moscow, the thought in the form of a doubt suddenly hit him. The thought told him that the gospel teaching of love was just psychological, and with a conscious effort he stopped himself praying.”[16] He continued his search instead through various eastern religions, meditation and yoga, “trying through these practices to come to know the unknowable and unattainable, the mystery of Being. It was a trend among the artists, especially of the Silver Age, to explore all types of esoteric practices and movements.”[17]

Spiritual searching through Art:

He continued to strive and search for answers through his practice as a painter. At his studio in Moscow “…he would labour for hours on end, straining every nerve to depict his subject dispassionately, to convey its temporal significance, yet at the same time to use it as a spring-board for exploring the infinite. He was tortured by conflicting arguments… In an effort to break out of the narrow framework of existence he took up yoga and applied himself to meditation…The one thing needful was to discover the purport of our appearance on this planet; to revert to the moment before creation and be merged with our original source. He continued oblivious to social and political affairs – utterly preoccupied by the thought that if man dies without the possibility of returning to the sphere of Absolute Being, then life had no meaning …”[18]

Sergei also studied the philosophical artistic thinkers of the time, searching to find a solution. From these the person who had the strongest impact was Wassily Kandinsky.

Kandinsky and ‘pure creativity’:

“In my young days, through a Russian painter who afterwards became famous, I had been attracted to the idea of pure creativity, taking the form of abstract art.”[19]

Wassily Kandinsky, Dreamy Improvisation, 1913, oil on canvas. Pinakothek der Moderne, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.[20]

Sister Gabriela describes how “…the concept of pure creativity answered Sergei’s longing and search to portray the unattainable and the infinite. Abstract painting was or seemed to be the best way to convey the inexpressible and intangible with visions of another new creation.”[21]

Kandinsky taught that art should serve the development of the soul, writing: “Painting is an art. Art is not the senseless creation of things, diffused in a vacuum. It is a powerful force and has many aims. It should serve the development and refinement of the human soul.”[22] This aligned with Sergei’s belief in art as a means to depict eternity and explore and solve the mystery of Being.

Kandinsky emphasised the importance of inner freedom and the necessity of the artist “to cultivate his inner life, from which the forms of new creation were to spring, expressing the artist’s inner dreams in his own uniquely constructed lines, shapes and colours.”[23] Sergei worked ardently in his search for the solution in his art, aiming “…not to copy natural phenomena but to produce new pictorial facts.”[24]

Concurrently, his work was interrupted by repeated periods of military service, as a junior officer in the engineering department which included working in the camouflage division for a time. Although he was never sent into battle amidst the violence and bloodshed, “the urgency of solving the question of Being was intensified by the daily horrifying reports of casualties from the front.”[25]

The return to figurative art:

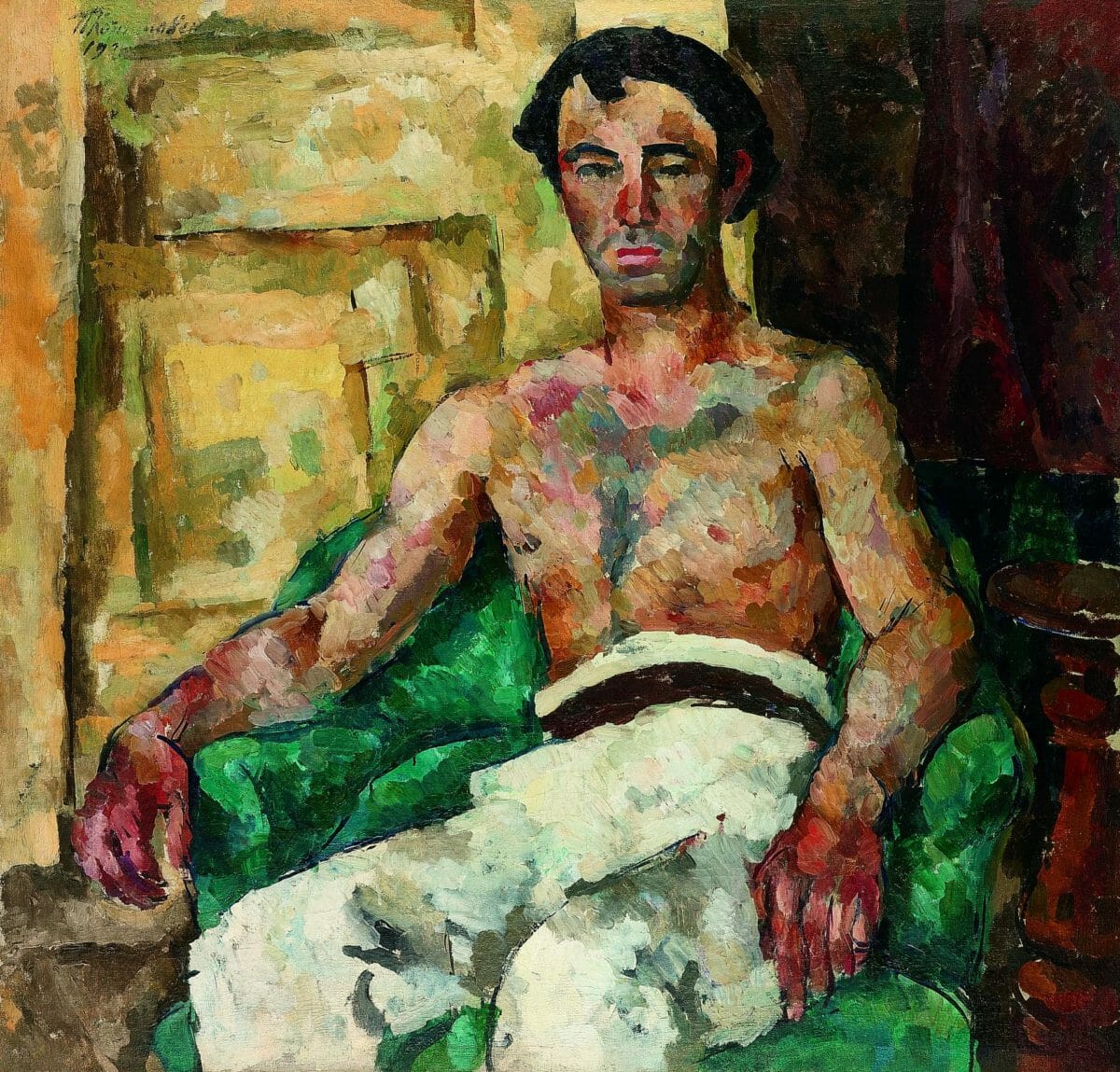

P. Konchalovsky, Portrait of Leonardo Benatov, 1920, oil on canvas.[26]

It was at the studio of Il’ia Mashkov, preparing for entrance exams to the Moscow Institute of Painting, that he met Leon (Levon) Mikhailovich Bounatian (1899-1972), who was known as Leonardo Benatov and of princely Armenian descent. He became a lifelong friend to Sergei and “from their very first contact they discovered that they shared a common striving: to try to attain and express the eternal in art and to attain to the mystery of Being.”[27]

It was 1917, a year of extreme instability. Sergei had no involvement in political matters and at the time of the Bolshevik coup d’état was ill with typhus of which was then epidemic. He was drafted into the army and…“although he was not involved in direct fighting, the acute situation only intensified Sergei’s inner suffering, bringing him to the brink of despair.”[28] At around this time he decided to move away from abstract art as his search through this means had largely failed to bear fruit. On this he later recounted that,

“…(abstract art) engrossed me for two or three years and led to the first theological thought to originate within my own mind…I soon realised that it was not given to me, a human being, to create from ‘nothing’, in the way that only God can create. I realised that everything that I created was conditioned by what was already in existence. I could not invent a new colour or line that had never existed anywhere before. An abstract picture is like a string of words, beautiful and sonorous in themselves, perhaps, but never expressing a complete thought. In short, an abstract picture represented a disintegration of being, a falling into the void, a return to the non esse from which we had been called by the creative act of God. I therefore abandoned my fruitless efforts to devise something new, and the problem of creative work now became closely linked in my mind with the cognition of Being.”[29]

He now endeavoured to seek and express the eternal through depicting the beauty and transcendence of nature, attempting to apprehend his Creator through the creation. This marked the beginning to his return to the God of his childhood and once more he started to pray.

It was in this context that in the summer of 1918 Sergei made his application to Moscow Institute of painting, Sculpture and Architecture, which had by then become SVOMAS[30] – or the Free State Art Studios. He, with Benatov, chose the studio of Konchalovsky, who had been one of their teachers previously in the school of Mashkov.

Konchalovsky, art training:

Sergei Simeonovich Sakharov, Self-Portrait, 1918, oil on canvas.[31]

Pyotr Konchalovsky, known as the ‘Russian Cezanne’, became Sergei’s teacher, and it was primarily from him that Sergei received his professional training in and understanding of art. A fatherly figure to his students, his classes provided training in drawing, painting, composition and the appreciation of Old Masters and their techniques. Konchalovsky’s main love, however, was for the work of Paul Cézanne, who was widely admired and appreciated in Russia at that time. Sergei had also become interested in the work of Cézanne, as for him it offered a vision and expression of the eternal, and “he saw his work as having more of a spiritual quality than other contemporary painters.”[32]

Each summer Konchalovsky would go to paint and rest at Abramtsevo (Абра́мцево), which was a private estate and artist’s colony 80 km north of Moscow. Originally founded in the 1600s, numerous notable artists and writers often stayed there, including Nikolai Gogol, Lev (Leo) Tolstoy and Ivan Turgenev, Vasily Polenov, Viktor Vasnetsov, Ilya Repin, Valentin Serov, and Mikhail Vrubel.

Konchalovsky painted there, much inspired by the unspoiled environment, and he also encouraged his students to observe and work from nature.

A. Lebedev-Shuiskiy, Silver Willow, 1921, oil on canvas.[33]

Following his example, in June 1920 Sergei and a group of seven artist friends went away for the summer to Barvikha (Барви́ха), 15 km west of Moscow, which “…was still a rural paradise with large trees, woods, meadows and lakes…Here they delighted in the calm and peaceful scenery which provided the perfect setting for landscape painting, finding subjects to renew their inspiration and to restore their belief in life after the terrors of the recent years in the city.”[34]

In Sergei’s words:

“The whole world, practically every visual scene, became mysterious, uncommonly beautiful, profound. Light changed, to caress and surround objects with a halo, as it were, of glory, imparting to them vibrations of life impossible for the artist to depict with the means at his disposal.”[35]

The young artists were captivated by the landscape, especially the trees, and the questions of colour, transparency, opacity and light became some of their main objects of study. Sergei thought deeply in particular about light, writing,

“How is it possible that a ray of light, in itself something simple, divides into an infinite variety of hues, but acting as a whole it creates a picture which is forever alive, which changes unceasingly, and yet preserves something of oneness?”[36]

The trip proved to be a turning point for each member of the group, and they continued their work upon returning to Moscow in autumn 1920.

‘Bytie’ – the meaning of ‘Being’:

Sister Gabriela informs us that, “during all this time the question of eternity, of how to express the unattainable, of the search for Being, had not abated but was continuing to gnaw away at both Sergei and Benatov [and that]…the other young painters shared their quest…Their common aim was to try to find an expression for the eternal. It was in this context that Benatov came up with the idea that they should form an association to consolidate and further develop their ideas, and name it ‘Bytie’ (Being).” Being, p. 43.

Photograph of the ‘Bytie’ (Being) group members.[37]

From left to right: P. Sokolov-Skalia, unknown, Z. Bogoiavlenskaia, P. Pokarzhevskii, L. Bounatian (Benatov), A. Lebedev-Shuiskiy, G. Stretenskiy.

The inspiration for the group was their aim to portray the eternal, all members being of the same heart and mind. Of his own work at that time, Sergei wrote:

“I was in a hurry to live. I did not want to waste a single hour, anxious to acquire as much knowledge as possible…I had a studio in Borby Square, and as I worked there at my painting I was constantly preoccupied by the thought of transition to the eternal. I didn’t like to put my mind to decorative art – we used to call it ‘easel-art’, meaning it was merely commercial. My work on every landscape or portrait took hours and hours. And my thinking would be lost in the feeling of the mystery of nature. Usually we encounter the phenomenon that people look at objects – the sky, a house, a tree, people – simply to find their orientation. But for me each one of these was an inexpressible mystery. It was a wonder to me how this vision comes into being.”[38]

Sergei participated in their first exhibition which opened on 1 January 1922. It is not known what work he exhibited, only that he was a participant and that the event was met with positive critical acclaim. A visitor to the exhibition related that “…the exhibition attracted much attention and was widely discussed. The press was very sympathetic to the initiatives of the young artists.”[39] V. M. Lobanov (1885-1970), an art historian, recounted that “the members of this artistic organization expressed their creative acts in beautiful and colourful searching, striving through painterly skill and mastery to portray the surrounding nature through the eyes of a new person.”[40] The art critic A. A. Sidorov (1891- 1978) wrote that the group of young painters had “the boldness to stand independently on their own two feet. The level of their mastership is doubtlessly high.”[41]

At the time of Sergei’s involvement, the position of the group was unique and non-conformist. However, as freedom of expression was gradually curtailed, the group ‘Bytie’ moved in a different direction, still promoting figurative art but losing its inner, spiritual dimensions and gradually becoming increasingly politicised.

Moving On:

However, Sister Gabriela relates that lasting involvement in ‘Bytie’ was not the future for Sergei who “…had long been looking for a way to leave Russia, fearing to be drawn into the red army again and knowing that he could be imprisoned a third time which would likely end in execution. The uncertainty of the times was unbearable, arrests were common and many people disappeared without a trace. It was a tradition for Russian artists to visit Italy and Paris at some time in the beginning of their career and when Benatov received a grant to study abroad, Sergei decided to join his friend.”[42]

In August 1922, shortly after the exhibition, Sergei and Benatov left Russia, sailing from Novorossisk on a Turkish ship, bound for Italy. Visiting numerous Italian artistic sites, they then travelled on to Berlin, again painting and visiting art galleries, and then in the latter part of 1922 they travelled to Paris, where they both settled.

Following this section, which furnishes the reader with the background and inception of his search for Being, some of the recurring and defining themes in the theology, thought and art of the future Saint Sophrony are explored.

Being, non-Being and the Abyss:

Sergei Sakharov, Dunes, early 1920s. Painting destroyed in fire.[43] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Sister Gabriela contextualises the concept of ‘the abyss’, telling us that “in the early 20th century, during the apocalyptic time of the Russian Silver Age, the abyss was used as an image to describe the fleeting nature of the insecure and unstable world of that time. Set against this was the image of the homely samovar, demonstrating what an every day reality the prevailing sense of the abyss had become.”[44] However, for Sergei it took on a more specific meaning, in relation to his unfolding spiritual experiences and state:

“I can remember myself as I was then, behaving in everyday life like any of my contemporaries though there were moments when I could not feel the earth under my feet. I could see it with my eyes but in spirit I was moving over a bottomless abyss.”[45] “I was living as if in a dream. And that dream was a nightmare…at times a dark abyss opened under me and a thick leaden wall was looming over me. I was twice arrested at the beginning of the revolution. Many people perished at the time but I felt no fear, as if there were nothing terrible in those arrests. But the vision of that wall and that abyss put me in a state of inexplicable, silent terror. And this went on for many years.”[46]

The continuous sense of the abyss and the remembrance of death followed him everywhere:

“Perpetual oblivion, as the extinguishing of the light of consciousness, filled me with horror. This state of the spirit settled in me, against my will. Everything that was happening in the world reminded me forcibly of the inevitability of an end to human history. A vision of the abyss was always there, only occasionally allowing me a moment’s peace.”[47]

Growing up throughout a period of endless conflict and turbulent political events, he was deeply affected, later writing that,

“The atmosphere reeks with the smell of blood. Day after day the universe is fed with news of the slaying or torture of the vanquished in fratricidal conflicts. Black clouds of hate screen the heavenly Light from our eyes. People make their own hell for themselves.”[48]

The tragic situation tormented Sergei to such an extent that within him,

“the memory of death was born…together with an awareness of the absurdity of all earthly possessions…My attention gradually turned from all my surroundings and concentrated within me, focussing on the question ‘is man eternal, or are we all to return to the darkness of non-being?’ My soul was pining in search for an answer to the question that had become more important for me than whatever was happening in the world.”[49]

“Art was for me a way to gain knowledge of being. That was how I perceived it, how I lived in it. It required the whole of me; even more than the whole. Unless one submits oneself to art entirely, it never becomes genuine, i.e. such an art that takes its servant beyond the limits of time and space. Truly artistic is only a work that carries inside elements of the eternal; else, it remains just an ornamental decoration of our dwelling.”[50]

The acute spiritual reality and sensation of the abyss was to remain with Sergei throughout his life, later emerging in his theological teachings. For example, while a spiritual father on Mount Athos, the by then Father Sophrony advised a hermit who had come to question him about spiritual life,

“Stay at the edge of the abyss, and when it gets too much, step back from the edge and take a cup of tea.”[51]

And in a later description of the ascetic path, writing that,

“In spirit [the ascetic] sees the abyss of ‘outer darkness’, opening wide before him, and so his prayer is ardent. There is no describing the mystery of this vision or the intensity of the struggle, which may last for years until the heart is purified of all passion, until the Divine light appears which reveals the falsity of our former judgements – the Light which leads the soul to the infinite expanses of true life.”[52]

From the Abyss to the Knowledge of Being:

Rather than acting as a negative force, Sergei’s ever-present and consuming awareness of death and the abyss provoked his profound and far-reaching search for the reason of existence, the purpose of being and eternity. It seems that the abyss itself also had a positive aspect:

“The touch of Divine love in the heart is our first contact with the heavenly side of the abyss.”[53] Gradually “…a new vision of the world and its meaning opened before me. Side by side with devastation I contemplated rebirth.”[54] “What was taking place in me proceeded from some superior source, independent of my will or any initiative on my part. I did not understand what was happening in me and yet I held it sacred.”[55]

Eventually, “he was given to understand that the author of life is a person, a Being, knowable and attainable. With this discovery he started praying again, asking the Being to reveal himself. Slowly, through different experiences he came to the knowledge that Christ was this Being, the Creator and author of life…Sergei gave himself over to prayer, striving to come closer to the Being, his whole aim now was to learn to know and enter into a personal contact with Him.”[56] Of this, Archimandrite Zacharias, the disciple of Saint Sophrony explains,

“We would never be able to know the true God if He Himself did not bridge the chasm which lies between Him and us, created beings. Our God is not a human invention but the One Who truly IS, the true God, Who from His excessive love, reveals Himself to man.”[57]

Later in life, Father Sophrony wrote the following in summation:

“I AM THAT I AM. Yes, indeed, it is He Who is Being. He alone truly lives. Everything summoned from the abyss of non-being exists solely by His will. My individual life, down to the smallest detail, comes uniquely from Him. He fills the soul, binding her ever more intimately to Himself. Conscious contact with Him stamps a man forever. Such a man will not now depart from the God of love Whom he has come to know. His mind is reborn. Hitherto he was inclined to see everywhere determined natural processes; now he begins to apprehend all things in the light of Person. Knowledge of the personal God bears an intrinsically personal character. Like recognizes like. There is an end to the deadly tedium of the impersonal. The earth, the whole universe, proclaims Him: ‘heaven and earth praise him, the sea, and everything that moves therein’ (Ps. 69.34). And lo, He Himself seeks to be with us, to impart to us the abundance of His life (cf. John 10.10). And we for our part thirst for this gift.”[58]

Now, seeking knowledge of the finally found and ultimate Being, Christ, Sergei’s prayer of repentance engulfed his entire person, however, this quickly began to conflict with his painting, which also demanded his entire self:

“This battle between art and prayer, that is, between two forms of life which require the whole of man, continued within me in a very intense manner for a year and a half or two years. In the end I was convinced that the means at my disposal in art would not give me what I was looking for. That is, even if I could intuitively sense eternity through art, this awareness is not as deep as in prayer. And I decided to give up art – which for me was a terribly high price to pay.”[59]

His recognition of Christ as the Creator and personal Being occurred whilst living in Paris, gradually from 1923 to 1925. During this time, he also frequently exhibited his paintings, and received critical recognition, exhibiting at the Salon d’Automne in 1923 and the more exclusive Salon des Tuilleries in 1924. However, painting ceased to hold the same meaning for him as he became increasingly drawn by the desire to know his Creator through prayer. He abandoned his painting and enrolled in the newly opened theological Institute of Saint Sergius[60] in Paris although after a short time found that this also did not facilitate the prayer he so craved:

“…despite all my interest in the life and history of the Church my spiritual need to dwell in prayer was impaired, and I departed for Mt. Athos.”[61]

Mount Athos and Saint Silouan:

Sergei arrived on Mount Athos in the autumn of 1925 and entered the Monastery of St Panteleimon, where he finally found the ideal conditions to give himself unhindered to prayer. Over the following five years he was tonsured and given the name Sophrony, and eventually, in 1930, he met the elder, Staretz Silouan, the meeting with whom would irrevocably change the course of his future life.

St Silouan the Athonite, Mount Athos, c. 1937. (Note: This is the first publication of this photograph of St Silouan). Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Detail from one of Saint Sophrony’s icons of St Silouan the Athonite, 1988, egg tempera on wood panel. Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Chapel of Saint Silouan, iconostasis.[62] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Sister Gabriela relates that “St Silouan had lived a similar extreme spiritual life at the edge of the abyss and from the knowledge he had gained was able to explain the various states that Sergei, now monk Sophrony, was experiencing.”[63] Of him, Father Sophrony later wrote,

“The Staretz was unlettered but no one could surpass him in craving for true knowledge…Christianity is not a philosophy, not a doctrine, but life, and all the Staretz’ conversations and writings are witness to this life.”[64]

Despite his immersion in the life of prayer, questions related to creativity continued to follow Father Sophrony throughout his life.[65] On meeting the elder Silouan he finally received an answer to his patient searching on the subject:

“…where creative work is concerned, in his ultimate search man gradually abandons all that is relative and temporal, in order to attain undying perfection. On this earth perfection, to be sure, is never absolute. And yet we may call them perfect who speak only what is given to them by the Spirit, in imitation of Christ Who said, ‘I do nothing of myself; but as my Father hath taught me, I speak these things’. This creative work is the noblest of all work available to man. Man sets out, not passively but in a creative spirit, towards this ideal, but always remembering to avoid any tendency to create God after his own image.”[66]

Father Sophrony’s association with St Silouan proved to be the defining relationship of his life, and before his death the elder Silouan left all his writings to his disciple. After his beloved Staretz’s repose, Father Sophrony retreated to dwell in a cave on Mount Athos, embracing life as a hermit so as to be immersed more completely in prayer. He remained in this ‘desert’ throughout the tumultuous and devastating years of the Second World War. Sister Gabriela recounts that “…Father Sophrony prayed ardently for peace during these terrible years of war and slaughter. At this time he was also called upon to become the spiritual director of three monasteries,[67] and in order to serve this ministry was ordained to the priesthood.[68] He continued however living in the ‘desert’ until after the Greek Civil War when he decided to return to the world to edit and publish the writings of his elder.”[69]

The publication of the Staretz’ work necessitated him to leave the Holy Mountain, and thus he returned once more to Paris. After arduous dedication to the project he published a personally roneo-typed first edition of the Staretz’ writings in 1948, entitled Staretz Silouan. He realised however that many “‘modern’ educated people were not able to perceive the profundity of the Staretz’ writings…So he found himself obliged to write an explanatory part to the writings,”[70] which were this time printed, and followed four years later.

A metal type letter and its printed impression designed by Saint Sophrony for the expanded edition.[71] Images: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

After the publication, due to years of immense exertion and many privations Father Sophrony became dangerously ill and required a major operation which left him partially invalided and unable to return to Mount Athos. He retreated to a nursing home in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, a verdant suburb of Paris, where after some time he was able to convert a former goat stable into a chapel[72] in which to hold services. His strength was greatly diminished but he spent the little he had in consoling the people who turned to him for spiritual guidance. A group of young men and women who had been greatly inspired by the recently published writings of Staretz Silouan steadily gathered around Father Sophrony. They desired to lead the monastic life and thus began their search for a location in which to form a new monastery.

The Monastery of St John the Baptist, England:

An historic yet vacant Rectory was found in the English countryside and Father Sophrony with his small community of those who had gathered around him in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois moved there on the 5th March 1959. Here they began to organise their monastery, although Father Sophrony was not expected to live long due to the severity of his surgery and greatly weakened health. However, “in fact he was to live for another 34 years and see his monastery grow beyond all hope and expectation…Throughout all this time, though he was busy building and establishing his monastery, the prayer did not slacken, he was forever searching for a closer and fuller relation with Christ, the Being.”[73]

This was the moment that he finally resumed painting, although now focussing entirely on the icon. Throughout the preceding years he had not ceased to reflect on the matter of creativity, especially our Creator’s approach to it, saying,

“Art has something that can help one to come nearer to the first Artist. As curious people used to look behind my back at what I was painting when painting in plein-air, so, in the same way, it would be good to be able to stand behind the back of God and watch Him creating.”[74]

“Having now found the true Being, Christ, and having learned to know Him as a person, establishing a living contact with Him through prayer and ascetic life, Father Sophrony arrived at a state where he could turn to art again. This time though, art was not a means to search for the solution of the problem of being, but to try to express what and Whom he had learned to know, the True Being.”[75] In the words of Archimandrite Zacharias on creativity,

“When we receive His grace we also have the gift of creativity; we become co-workers with Him in our re-creation, in our refashioning and our regeneration. When we receive this grace our heart is enlarged to embrace heaven and earth and to bring every creature before God, that is, to spread the creative energy of God over all creation.”[76]

It was in order to deepen his exploration of prayer and his Creator that he took up icon painting, and for the rest of his life the striving to worthily depict and make a true icon of Christ remained one of his greatest preoccupations, he was never satisfied but with each attempt came gradually closer to his goal.

Painting True Being in the Icon:

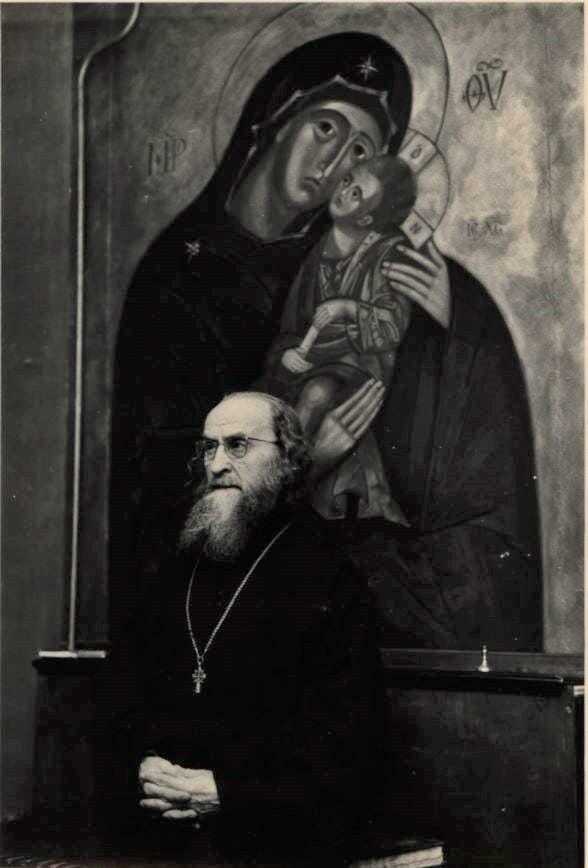

Archimandrite Sophrony, in front of his icon of the Mother of God and Christ Child, early 1960s.[77] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Their first task at the monastery was to make a chapel within the Old Rectory and, although only having arrived at the beginning of Lent, it was ready in time for Holy Week and Easter. They installed the iconostasis from the chapel in France, which had been painted by Père Gregoire (Krug), and a number of icons painted by Leonid Ouspensky, including the earliest icons of Staretz Silouan[78]. Drawing on Father Sophrony’s experience as a painter, a carefully designed icon studio was then constructed, which Sister Gabriela describes as being built on the foundations of a disused pigsty and having structural components from a hen house with brick additions and glazed roof panels.

Father Sophrony was now able “to occupy himself more fully with this work to convey visually all that he had found and learned during his lifetime. As a young man he had felt constrained to give up his painting in order to strive for a fuller knowledge and contact with Him whom he was seeking; now he sought to depict this same Person in paint. The most suitable means for this was the iconography of the Orthodox Church. He had lived with and studied the wall paintings and icons on Mount Athos, becoming familiar with the different schools and varied styles developed over the centuries. He had contact with icon painters who had shared their model drawings with him, so although he did not produce many icons himself, he had nevertheless been studying the work in depth.”[79] Many years later in a letter to his sister Maria, he wrote:

“However strange it may appear, despite the fact that I am already an old man, and have not worked as an artist for 36 years, I see that this ‘vein’ has remained alive in me. What I am seeing once more in myself was in its time the cause of my totally forsaking painting. It is impossible to be divided inwardly to such a degree. If you want to do something, let’s say something that could be ‘bearable’, inevitably one’s full attention must be devoted to this work, which stands in contradiction to the other quests of my soul. But we shall see what God disposes.”[80]

Those areas with which he was less familiar, such as painting in egg tempera, he studied diligently and endeavoured to follow all the practices of traditional Orthodox iconography, teaching his apprentices the importance of doing the same. His earlier academic art training also helped him in many ways. Subjects such as pictorial composition, colour theory, texture, the study of nature, and knowledge of anatomy and especially the face, all now came to serve in his work in iconography. Although he made use of and taught all these areas, nevertheless, he emphasised that his more classical academic way of painting was not to be copied. He always urged his followers to study and use traditional iconographic techniques, teaching areas such as the principles of stylisation and abstraction, the importance of beauty, harmony and calm, and the application of light in the icon.

Father Sophrony in his late 80s painting abstract mountains in the Chapel of St Silouan, 1985.[81] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Sister Gabriela tells us that “in iconography he found a fulfilment of the various techniques he had learned, even the abstract, since the icon, if seen in its details, is composed of abstract components: the garment, mountains, to a certain extent buildings and even faces, carry aspects of abstract art. These abstract components, though not visible or noticeable without a closer study, form an essential part of the icon, giving it its strength and structure.”[82] Of this, Father Sophrony commented,

“Mountains in icons are like abstract art. But in iconography this abstract art has a meaning.”[83]

The Face:

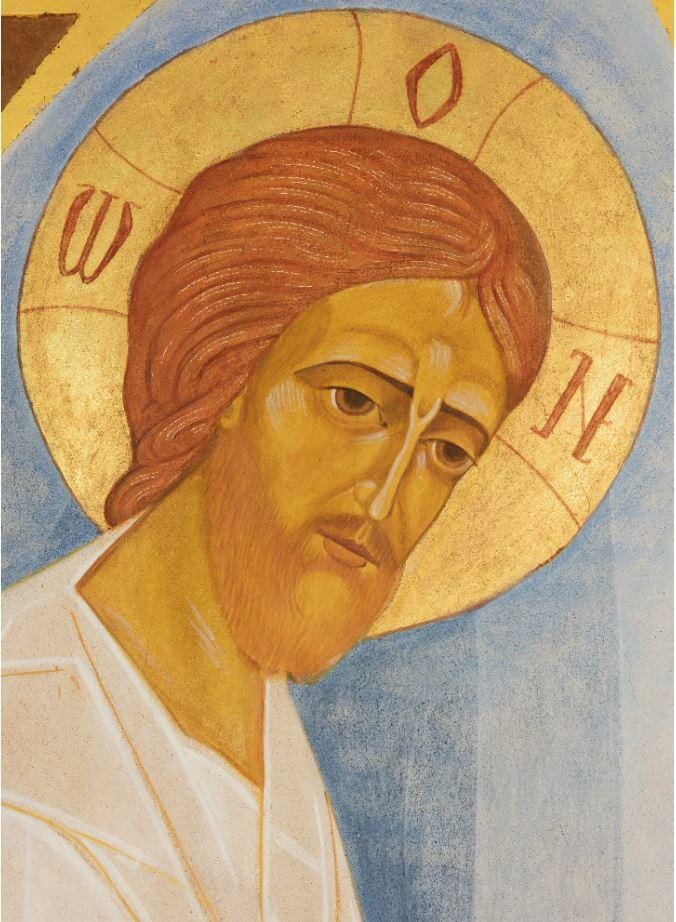

Saint Sophrony, detail of the Face of Christ at the Resurrection, early 1980’s, wall painting. Monastery of St John the Baptist, Refectory.[84] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Saint Sophrony had long held a great interest in the face and from his early days as a painter had earned his living as a portrait painter. He considered the face to be the most important aspect of the icon, reflecting the person’s inner life, soul and unique being. Sister Gabriela writes that although “the phenomenon of the person remains a mystery,…the person is depicted on the face, by the face; the face reveals an echo of the soul”[85], consequently “the language of icons offered Father Sophrony another and new way to render the soul and the inner person. The icon captures all the external aspects in its stylization, and thus also touches upon the inexpressible.” Being, p. 105. Furthermore, he observed that,

…even the most ugly faces become beautiful with grace.”[86]

He often emphasised the absolute importance of prayer in iconographic practice, especially to help perceive the person of Christ, for example he instructed his young apprentice to,

“Always pray when you paint! Pray that we may see, learn to know Christ. Pray to St John the Baptist that he helps us to see Christ – he was the greatest among the prophets because he was the first who knew Him.”[87]

Regarding stylization he “…emphasised that the stylization of the faces should be moderate, not too exaggerated, neither too expressive, nor too stylized, but it was essential to keep an aspect of beauty in them…The faces must not be too naturalistic, yet still stay human and not be over transfigured.”[88]

For Father Sophrony “it was precisely the eyes that carried the most importance, as they would reflect the inner man, the soul. Father Sophrony had several thoughts on how the eyes were best represented, and developed a style of his own. He preferred to give a calm and interior look to the faces he painted, letting the eyelid cover part of the iris and touch the upper part of the pupil, thus avoiding a too direct and intensely focussed look.”[89]

Mother of God and Christ Child (detail), early 1960’s, egg tempera on hardboard, monumental size icon in the study of the Old Rectory.[90] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

He also loved to paint the Mother of God, and one of the earliest icons he painted at his monastery was a monumental size icon of her with the Christ Child for the chimneybreast of his study. In her icons, he often added a pronounced shadow line along the side of her face and jaw. This imparted qualities of depth and seriousness, while also subtly emphasising the stylization. Sister Gabriela tells us that “He did not like her icons to be too sweet… It was better to avoid soft modelling, which easily gives a sweet and soft expression as did the use of red in the colour palette. He preferred her to be serious…

My icon of the Mother of God is strict but with a mildness as well. A dark shadow on the cheek line can give a good effect.”[91]

Texture, Colour and Light:

The surface and qualitative characteristics of the work were of immense importance to Father Sophrony, and for him “the most important aspect…was that the surface should have a ‘culture’ and ‘nobility’, meaning by this that if it is worked to a perfect state it will reflect upon the entire work which will then emanate a nobility that is felt unobtrusively and yet becomes the hallmark of a masterpiece.”[92] Father Sophrony explained that,

“The surface is very important, not to the touch, but for the eye. The surface of an icon is like porcelain.”[93]

Saint Sophrony, Seraphim Angel detail from the icon of Christ in Glory, 1974, egg tempera on wood panel. Church of Saint Michael, Welling.[94]

In terms of colour, “Father Sophrony also paid great attention to colour, its interrelations and effects. He knew which colours would enhance one another, which would complement and those which would cancel each other out.”[95]…“He was equally conscious of the importance of the proximity of tone and outlines. Sometimes the garments were constructed through the interplay of adjacent colours, volumes and shapes.”[96]

“To see the values of the colours, one has to see them all together. Be brave and paint colours – it also depends on the surroundings if they work or not.”[97]

Colour had preoccupied him from his youth, especially sky blue or azure.

“When I was young I liked to lie on the bench in the garden and look up at the blue sky. Later I understood that blue light is an image of transcendence. There is nothing similar on earth to the blue colour of the sky.”[98]

On this he later elaborated, recounting that,

“…when, by a gift from on High, it was vouchsafed to me to behold the Uncreated Light of Divinity, I saw the blue sky of our planet as a symbol of the radiance of the heavenly glory. This radiance is everywhere – filling all the depths of the universe, ever intangible, other-worldly for the created world. Azure-blue is the colour of transcendency.”[99]

Saint Sophrony’s Icon of Christ in Glory demonstrating the heavenly glory of azure, 1974, egg tempera on wood panel. Church of Saint Michael, Welling.[100]

In later life he developed a special shade of greenish grey blue, to communicate a sense of space and infinity. He sometimes used this as a colour for the ceilings in his chapels (initially at his chapel in Paris), to express the boundless expanse of the heavens and eternity.

Another matter of greatest importance to Father Sophrony, reflecting his lifelong fascination with the subject, was that of the rendering of light. As Sister Gabriela observes, “Light is one of the attributes of God, He often reveals Himself through light.”[101] Father Sophrony also often reflected upon and wrote of the Uncreated Light which,

“…by its nature is absolutely different from ordinary physical light. Contemplating it begets, first and foremost, an all-absorbing feeling of the living God…In the spirit he [man] beholds the Invisible, breathes Him, is wholly in Him…Faith is light, but in small measure. Hope is light but not yet perfect. The perfect light is love.”[102]

Aware of many ways of representing light both within interiors and the icon (including the use of transparency, gilding, the juxtaposition of light and dark), for his Chapel of Saint Silouan he chose to use specially modulated matte gilded surfaces for the ceiling and upper echelons, the light being “reflected off the gilded ceiling, which bathed the whole atmosphere in a golden light.”[103]

Depicting the True Being, Christ:

Saint Sophrony painting Christ at the Last Supper, early 1980s, wall painting. Monastery of St John the Baptist, Refectory.[104] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

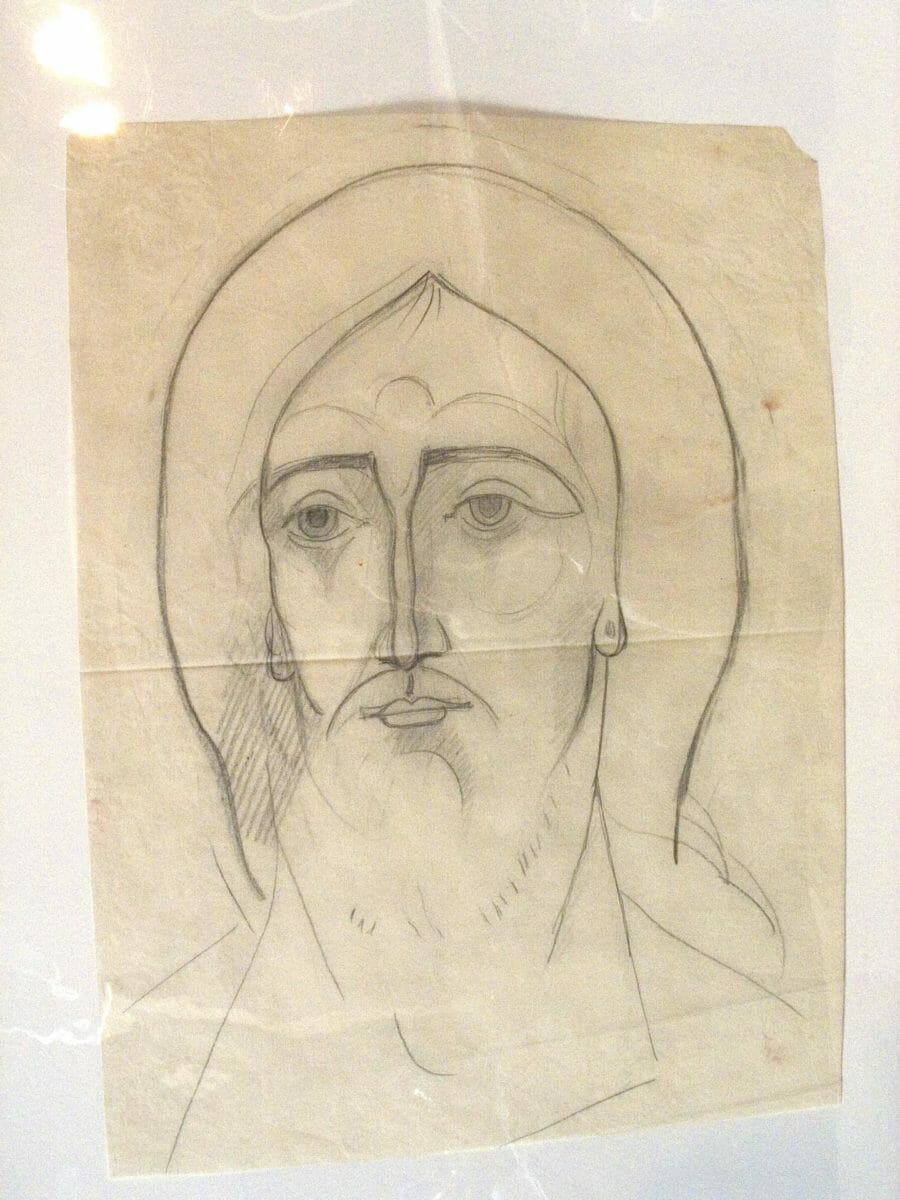

Sister Gabriela explains that for Father Sophrony “the most important and essential question remained: How to portray Christ – the true Being – Whom he had come to know through his long, intense search and struggle. The fact that Christ was a person, fully attainable and – as such – depictable, only party facilitated the problem. As both perfect man and perfect God, both natures had to be represented. The divine, naturally, cannot be depicted, and to try to do so brings a danger of falling into sentimentality, yet to concentrate on the fully human side may equally have the same result. The stylization of the icon leant itself to a more ‘detached’ image, which could hold together the two aspects of human and divine. Father Sophrony knew that it was impossible to attain to a full and correct representation, and that each icon at best could only catch a small fraction of Christ. To paint the perfect icon was beyond human means. However, he never tired of trying, and made countless drawings and sketches for the many icons and murals on which he worked, always striving to draw nearer to his goal.”[105]

Saint Sophrony, Face of Christ, preparatory study for a wall painting of the Resurrection, 1985, pencil on greaseproof paper. Monastery of St John the Baptist, for the Chapel of St Silouan.[106] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Whilst Father Sophrony believed that it was ultimately not possible to depict the true likeness of Christ, he nevertheless likened each attempt to a springboard from which one may ascend towards Him, saying that, “Contemplating the icon of Christ, in spirit we rise into contact with Him. We confess His manifestation in the flesh – He is both God and man, wholly man and perfect Divine likeness. We go further than colours and outlines into the world of the intelligence and the spirit.”[107]

While Saint Sophrony’s foremost reason for painting icons was the desire to represent true Being, Christ. Nevertheless, “the icon with its language of stylization and emphasis on the interior life, was the most appropriate to convey what he had learned and found”[108] not only in relation to Christ but also with regards to other spiritual themes and persons. Over the years he had formed many thoughts on icon painting and expression. In another letter to his sister Maria, he wrote:

“I have been forced by the work on icons itself to plunge into the depths of past centuries. I have been thinking about those artists, spirit-inspired iconographers, who strove to express, in the material flesh of the ICON, the union of Uncreated with created. Some of them intentionally ‘distorted’ the human face, using this means to tear the mind of the person praying away from the earth, so as to transfer it to a world of another dimension. Others, while holding essentially the same views, sought the connection between the image and the Prototype and expressed both dimensions, i.e. the temporal and the eternal, in human features. But they have transfigured these human features, and they never allowed themselves to descend as far as naturalism, which the Western painters in the age of the Renaissance did not escape. It is relatively easy to create an image pleasing to the eye by a hint, by a sketch. But exceptional genius is needed to ‘complete’ a work without sinking into ‘carnal beauty’. The wonderful history of the Icon knows many master-artists; some of them preferred to violate all the proportions or traits – others, such as St Andrei Rublev, created an exceptional harmony of two worlds in works of a rare completeness. I like both the first and the second. But the second stand higher in my estimation as true spirit-inspired artists and masters.”[109]

Conclusion:

In summation, Sister Gabriela tells us that “Father Sophrony’s search for Being was, as we have seen, the ‘leitmotiv’ of his life…His searches led him to an abyss, to the edge of the unknown, from where there was no turning back…He came up against an impasse which only a leap into the unknown could resolve. He took that leap of faith by which he found the long desired fulfilment of his search in the meeting face to face with his Creator, the true Being. He understood that what he had been longing to know was revealed as a Personal God…His leap of faith brought him not only safely across the abyss, but to a height from which he viewed that which surpassed his every hope and imagination…[and] his life took wings like the eagle…”[110] “Now there was no further question of an abyss of darkness and of non-being, but rather a new endless horizon lay before him; the abyss had been transfigured by light…”[111]

From thenceforth in the realm of one who has come to know his Creator, having discovered the true Being and his Creator, Christ, Saint Sophrony’s life was thereafter dedicated to all-consuming fiery prayer, which purified his heart and entire personhood. It was “while a monk of Mount Athos, [that] Father Sophrony has learned the practice of hesychastic prayer, known as prayer of the heart. This form of prayer was especially emphasised in the 14th century by St Gregory Palamas, (1296-1359), who developed a school of theology of uncreated light and prayer. This form of prayer is directly linked with the apprehension of Being and is centred in the heart, the meeting place between God and man. The heart, which is the hidden deep centre of man, is capable of reflecting the image of God like a mirror, depending on its state. The purer the heart, the clearer and more luminous is the reflected image.”[112]

Archimandrite Zacharias elucidates on this, saying that,

“Our heart must always be crushed by the precepts of Christ, by the grace of God, because just as an image can be imprinted on soft warm wax, in the same way, the image of Christ can be imprinted on a soft heart.”[113] “In the Jesus prayer we keep repeating the Name of Christ as if we were filing off rust which we have accumulated in this world, so that this material which is covered with rust may become shiny again, so that we may shine again. If we file off the rust we have accumulated in this world, then that primordial gift of God which we received at our creation will increase, will develop and it will save our souls, that is to say, it will bring us to a full likeness with our Creator.”[114]

This is the path which Father Sophrony trod and to which his iconography bears witness, testifying to his experiential-theological vision forged over many decades. He also advocated theological study, advising his young apprentice-iconographer that,

“…we need to know theology. The most important is to follow Christ’s commandments. You will come to theology through the icons, it will be like a crown on the work.”[115]

Reflecting on his path, both artistic and spiritual, Sister Gabriela explicates further, saying that “Father Sophrony’s icons, way of painting and thoughts on iconography are highly personal. They reflect his unique path of development rooted in the Russian avant-garde of the 1920’s, passing through an intense period of spiritual search which led him to Christ and culminated in him expressing all that he had found in paint…His offering to the icon is to bring things back to the essential, to give a minimalistic message, concentrating on what matters: the person, both the one depicted on the icon and the viewer, inspiring a living relation between them.”[116]

*************

‘Being’: The Art and Life of Father Sophrony, by Sister Gabriela, first edition. The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex, 2016. Hardcover, pp. 176, 25 colour plates, 8 black & white plates, ISBN 978-1-909649-07-1. It has also been translated into Greek, Russian, Romanian and French.

This and other books from the trilogy can be purchased from The Patriarchal Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, The Old Rectory, Tolleshunt Knights, By Maldon, Essex CM9 8EZ, UK. Please write to Sister Magdalen.

The book is also available in a paperback version on Amazon.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

[1] Being, p. 148.

[2] Sister Gabriela, ‘Being’: The Art and Life of Father Sophrony, Tolleshunt Knights: Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, first edition. 2016.

[3] Being, p. 13.

[4] Being, p. 16. Giliarovskogo street, house 16, building 2).

[5] Being, p. 13.

[6] Archimandrite Sophrony, unpublished letter. Being p. 14.

[7] Archimandrite Sophrony, We Shall See Him As He Is, Tolleshunt Knights: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 1988, p. 37, Being, p. 128.

[8] Being, p. 15.

[9] Being, p. 17.

[10] 80 x 58cm, https://www.bukowskis.com/en/lots/719149-fedor-ivanovich-rerberg-kyrka-i-solljus

[11]https://arthive.com/viktorvasnetsov/works/376427~Triptych_the_Joy_of_the_righteous_in_the_Lord_The_threshold_of_Paradise_The_sketch_for_the_painting_of_the_Vladimir_Cathedral_in_Kiev_Fragment_Central_part

[12] Being, p. 62. RGALI, fond 680, op. 4, ed. Khr 73. “Lichnoe delo Sakharova Sergeia Simeonovicha”, 9 ioulia 1918, list 3.

[13] Archimandrite Sophrony, His Life is Mine, Crestwood: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1988, p. 38. Being, pp. 17-18.

[14] Being, p. 18.

[15] Sophrony, We Shall See Him, p. 13. Being, p. 18.

[16] Being, p. 19.

[17] Being, p. 19.

[18] Sophrony, His Life is Mine…introduction. Being, pp. 19-20.

[19] Archimandrite Sophrony, Wisdom from Mount Athos, Crestwood: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1974, p. 13. Being, p. 20.

[20] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-artist-kandinsky

[21] Being, p. 20.

[22] W. Kandinsky, On the Spiritual in Art, (1920), Experiment vol. 8, Los Angeles, 2002, p. 113. Being, p. 21.

[23] Being, p. 22.

[24] Sophrony, Wisdom, p. 13. Being, p. 23.

[25] Being, p. 26.

[26] Being, p. 32. https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2007/russian-art-evening-l07114/lot.48.html

[27] Being, p. 27.

[28] Being, p. 28.

[29] Sophrony, Wisdom, pp. 13-14, Being, p. 77.

[30] Svobodnye gosudarstvennye khudozhestvennye masterskie.

[31] Being, p. 63. Private Collection.

[32] Being, p. 33.

[33] Being, p. 40. Anatoly Adrianovich Lebedev-Shuiskiy, 53 × 42.5 cm. https://arthive.com/artists/23267~Anatoly_Adrianovich_LebedevShuisky/works/366048~Silver_willow

[34] Being, p. 36.

[35] Sophrony, Wisdom, p. 14, Being, p. 39.

[36] Archimandrite Sophrony, Letters to his Family, Tolleshunt Knights: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2015, p. 279. Being, p. 70.

[37] Being, p. 44. Otdel roukopisei Tretyakovskoi galerei fond P. P. Sokolova-Skalia: fond 56, ed. khr.24.

[38] Being, pp. 49-50.

[39] Lev Varshavskii, in Lebedev, Bor’ba, p. 115. Being, p. 57.

[40] Being, p. 48. Lobanov, Lebedev-Shuiskiy, Moscow: Sovetskii khudozhnik, 1983, p. 11.

[41] A. A. Sidirov, Sredi kollektsionerov, 1922, No 2 (February) in Turchin, Obrazy bytia, p. 81. Being, p. 59.

[42] Being, p. 60.

[43] Being, p. 79.

[44] Being, p. 66.

[45] Sophrony, We Shall See Him…, p. 12, Being, p. 65.

[46] Archimandrite Sophrony, Tainstvo khristianskoi zhizni, Sergiev Posad: Sviato-Troitskaia Lavra, 2009, p. 77, Being p. 29.

[47] Sophrony, We Shall See Him, p. 12, Being, pp. 72-3.

[48] Sophrony, We Shall See Him, p. 31, Being, p. 66.

[49] Archimandrite Sophrony, Tainstvo khristianskoi zhizni, Sergiev Posad: Sviato-Troitskaia Lavra, 2009, p. 77. Being, p. 67.

[50] Archimandrite Sophrony, Rozhdenie v Tsarstvo nepokolebimoe, Moscow: Palomnik, 2000, p. 163. Being, p. 74.

[51] Archimandrite Sophrony, On Prayer, Tolleshunt Knights: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 1996, p. 51. Being, p. 78.

[52] Archimandrite Sophrony, St Silouan the Athonite, Crestwood: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1991, p. 167. Being, p. 87.

[53] Sophrony, His Life is Mine, p. 62. Being, p. 90.

[54] Sophrony, His Life is Mine, p. 38. Being, p. 83.

[55] Sophrony, We Shall See Him, p. 15. Being, pp. 82-3.

[56] Being, pp. 83-4.

[57] Archimandrite Zacharias, Man, the Target of God, Tolleshunt Knights: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2015, p. 250. Being, p. 83.

[58] Sophrony, His Life is Mine, p. 26. Being, p. 151.

[59] Sophrony, Letters, p. 38, Being, p. 84.

[60] The St Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute (Institut de Théologie Orthodoxe Saint-Serge) opened in the summer of 1925.

[61] Sophrony, On Prayer, p. 40, Being, p. 85.

[62] Being, p. 110.

[63] Being, p. 87.

[64] Sophrony, St. Silouan the Athonite, Tolleshunt Knights: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 1991, pp. 110-11. Being, p. 87.

[65] Although he painted little during his time on the Holy Mountain, some icons have been attributed to him, mainly from the period following St Silouan’s repose (see Sister Gabriela’s Catalogue Raisonée).

[66] Sophrony, Wisdom, pp. 14-15. Being, p. 88.

[67] The monasteries of St Paul, Grigoriou and Xenophondos, as well as to a number of other hermits.

[68] On the 2nd of February 1941, becoming a spiritual father one year later.

[69] Being, pp. 88-9.

[70] Being, pp. 88-9.

[71] Images from, Sister Gabriela, Painting as Prayer: the Art of A. Sophrony Sakharov, Tolleshunt Knights: Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, first edition, 2017, pp. 163-4.

[72] This chapel is described in more detail in Seeking Perfection, and in the previous review.

[73] Being, p. 93 and p. 90.

[74] Being, p. 117. Quotation from the personal notes of Sister Gabriela.

[75] Being, p. 90.

[76] Zacharias, Man, Target of God, p. 250. Being, pp. 90-1.

[77] Being, p. 99.

[78] Made before his canonisation and thus without halo and inscription.

[79] Being, p. 94.

[80] Sophrony, Letters to his Family, p. 93. Being, p. 95.

[81] Being, p. 101.

[82] Being, p. 100.

[83] Being, p. 100. Quotation from the personal notes of Sister Gabriela.

[84] Being, p. 104.

[85] Being, p. 103.

[86] Being, p. 105. Quotation from the personal notes of Sister Gabriela.

[87] Being, p. 107. Quotation from the personal notes of Sister Gabriela.

[88] Being, p. 106. Quotation from the personal notes of Sister Gabriela.

[89] Being, p. 105.

[90] Being, p. 108. Situated on the chimney breast. See also previous photograph of Saint Sophrony in front of the icon.

[91] Both quotes from Being, p. 109. The latter quotation of Father Sophrony is from Sister Gabriela’s personal notes.

[92] Being, p. 112.

[93] Being, p. 112. Quotation from the personal notes of Sister Gabriela.

[94] Being, p. 140. Reproduced with kind permission of the Rector of St Michael’s Church.

[95] Being, p. 114.

[96] Being, p. 115.

[97] Being, p. 114. Quotation from the personal notes of Sister Gabriela.

[98] Being, pp. 69-70.

[99] Sophrony, We Shall See Him, p. 166. Being, p. 129.

[100] Being, p. 142. Reproduced with kind permission of the Rector of St Michael’s Church.

[101] Being, p. 128.

[102] Sophrony, St Silouan, pp. 171-172. Being, p.166.

[103] Being, p. 129.

[104] Being, p. 148.

[105] Being, pp. 138-9.

[106] 44.5 x 32.8 cm, Being, p. 131.

[107] Sophrony, On Prayer, pp. 166-7. Being, p. 144.

[108] Being, p. 130.

[109] Sophrony, Letters to his Family, p. 192. Being, pp. 130-2.

[110] Being, p. 161-2.

[111] Being, p. 163.

[112] Being, p. 169.

[113] Archimandrite Zacharias, ‘Tears, the Healing of the Person’, unpublished talk. Being, p. 169.

[114] Being, p. 170. Archimandrite Zacharias, unpublished talk.

[115] Being, p. 170. From the personal notes of Sister Gabriela.

[116] Being, p. 153.

Thank you. What an enjoyable and enlightening read.