Similar Posts

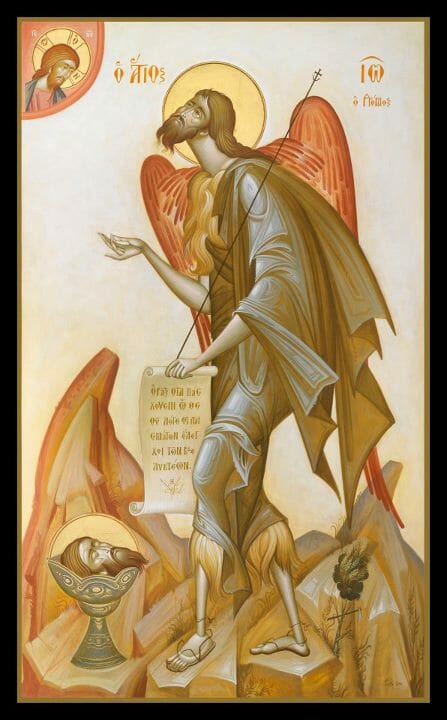

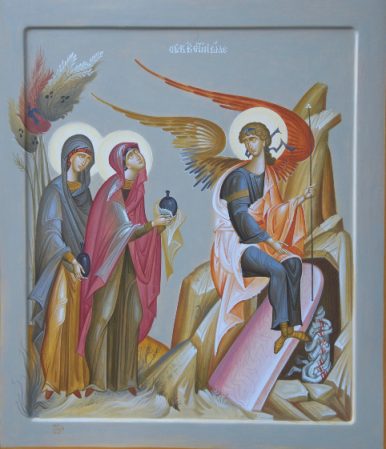

The Athens based iconographer George Kordis may perhaps be considered as one of the most important representatives of the revival of the icon. His approach to the icon is one that does not see working within Tradition as merely the repetition of old models, but rather as the application of immutable principles in solving contemporary pictorial problems. His unique style, at times considered “too modern” or innovative, challenges our expectations of the possible. This interview will serve to help us understand his methodology as the iconographer himself understands it.

Born in Greece in 1956, George Kordis studied theology at the University of Athens. He then pursued his studies in theology and the aesthetics of Byzantine painting at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology in Boston, gaining an MA in theology. In 1991 he was awarded his Doctorate in Theology at the University of Athens. In 2003 he was appointed to the post of Lecturer at the same university. Today he is assistant professor in Iconography (Theory and Practice) at the University of Athens.

In addition to his academic work, Dr. Kordis periodically lectures as visiting professor and teaches icon painting courses in the US (Yale University & University of South Carolina), Romania (School of Theology of Bucharest), Ukraine (Pedagogical University of Odessa), etc.

Dr. Kordis is also a prolific author. His book, “Icon as Communion: The Ideals and Compositional Principles of Icon Painting,” has been translated into English by Holy Cross Orthodox Press. It is worth noting as very useful, and one on the only practical guides available today for learning iconographic drawing.

In addition to portable icons Dr. Kordis has painted many churches. His most recent commissions in the US include: Holy Trinity Church, Columbia, SC; St Sophia, Valley Forge, PA; Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church, Carmel, IN; Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church, Pittsburg, PA; St. George, Antiochian Orthodox Church, Fishers, IN; St. Catherine, Greek Orthodox Church, Braintree, MA.

***

Fr. Silouan: It has become a truism to say that icon painting is not “art.” It seems to me that this is a half-truth. Yes, it goes without saying, that the icon is not to be understood merely according to the presuppositions of art as they have come down to us from the humanist Renaissance and the extreme subjectivism of Modernism. Nevertheless, it is an “art” in the traditional sense of “techne,” or craftsmanship, the skillful putting together of parts, or a making, according to a right course of reasoning (logos). Do you think it is important to reclaim an understanding of the icon as truly a work of art, involving the mastering of skill in pictorial principles, in order to safeguard it from a simplistic conservatism, often mistaken for Tradition, but that ultimately hurts its revitalization within in the Church?

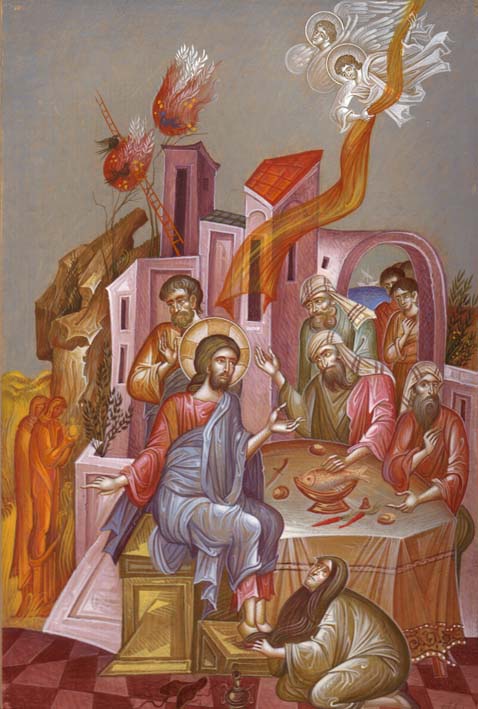

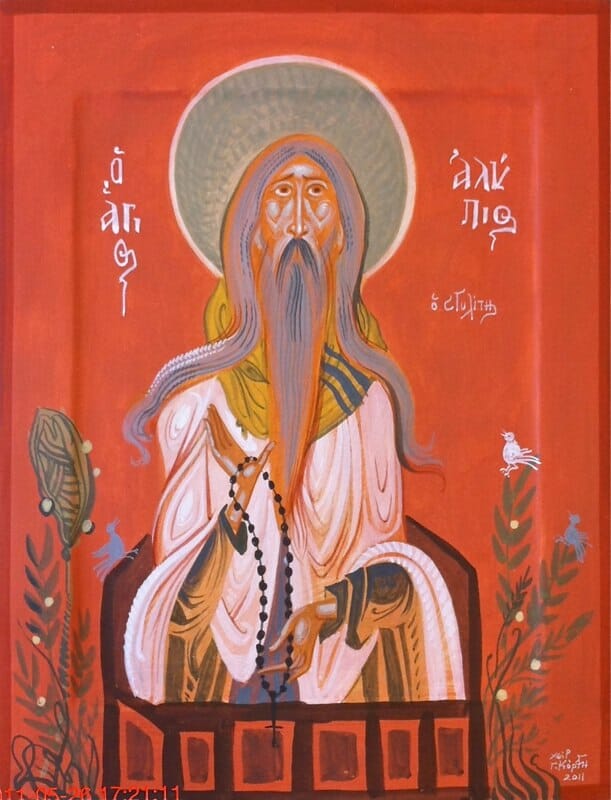

George Kordis: Yes. I believe that today in our postmodern world we have to rearticulate the meaning of icon painting in order to avoid any misunderstandings. According to Orthodox Tradition, which is declared by the Seventh Ecumenical Council and the fathers of the iconoclastic era, icon painting is an art with specific goals and character. As defined by St. Photius, patriarch of Constantinople, icon painting uses the media of art and, following the Tradition of the Church, its goal is to render the external form of any person depicted. For that purpose this art elaborates and transforms the form under one condition, the image must always be recognizable by the faithful beholder. First, the painter removes all elements that are inappropriate and satisfy only human curiosity, but do not serve the sacred mission of the icon. So the icon painter first makes the icon more abstract than a photo. And then, the artist renders this purified form in an artistic manner which is appropriate to the sacred person. He has to “invent”, to create a painting mode that is suitable and good. So, according to St. Photius, the art of icon painting is a functional art that serves the Christian Community and helps the faithful to be in contact with the events and persons it depicts. Of course, we have to analyze in detail the process the artist followed in order for these goals to be realized.

Fr. Silouan: In your book “Icon as Communion” you speak of “rhythm” in icon painting. You have also said that painting requires structure, otherwise, failing to grasp the whole, things remain in the realm of mere decoration. Can you please give us a definition of the concept of rhythm, how it relates to drawing, and how it is best implemented in the structure of a composition?

George Kordis: Rhythm is the basic instrument the painters during the Byzantine period used in order to achieve communion between the beholder-believer and the person depicted. The main idea was that the icon is not merely an image, a form on the wall of a church or on a surface of wood. The icon must be alive, must be a presence of the saint in the church. In this way the icon could demonstrate the belief that the Church is the living Body of Christ in time and space, where all members are embodied and live. In this perspective the icon should give the spectator the impression that whatever is depicted is alive, is present. More specifically they wanted to show that the person depicted comes to the dimensions of the spectator and is connected with him. So they had to create a system of painting principles that could serve this need. Rhythm was the basic instrument. Rhythm is a way of handling the movements and energies that exist on a painting surface. Any line or color is an energy. The painter could organize these movements or energies in order for the icon to enter the reality of the spectator and meet him. So they followed the way ancient Greek painters used rhythm. All lines shape an X on the surface and everything in the composition follows this X axis. In this way everything in any icon is organized properly, is united and creates a state of dynamic balance. There is always movement, indicating life and motion, and at the same time there is also stability that indicates eternity, a state of timeless reality. Through rhythm the icon is projected to the reality of the spectator. Color, light and perspective, are also used as vehicles to create this projection. We could say that rhythm is a vehicle creating unity in any Orthodox icon and contributes to fulfill its mission in the Church.

Fr. Silouan: You have previously contrasted the notion of virtual reality, which you see as arising from the developments of Western naturalism, with the use of pictorial space in Byzantine painting, which you refer to as real virtuality. Can you please summarize some of the differences between these two approaches to representation?

George Kordis: In naturalistic painting, developed in Western Europe after the Renaissance, the ideal for painters was to create an illusionistic painting that gives the spectator the impression that there exists a different iconic reality behind the surface of the painting. They thought that in this way the painting would be a real substitute of reality. But the consequences were very serious. In this way they created two separated realities that did not communicate. A real one and a false one. The reality of iconography [illusionist religious painting] was the false one. Christ and the saints appear as if they live in a different reality, away from our reality. The Body of Christ, the Church, seemed to be broken in pieces. The absence of Christ was evident to anyone who entered a church and could see a naturalistic painting. Christ was there as a painting but the spectator had the impression that the person was absent. So there were ecclesiological consequences.

In Byzantine painting, the mode chosen by the Orthodox Church for the rendering of icons, things were different. As I have already mentioned, the first and primarily goal was to visualize the unity of the Church, so that the spectator entering the church could immediately feel this truth. For that reason the pictorial space of the icon should be in front of the picture field and not behind. The space and time of the person depicted on the icons should be the same with the spectators. Therefore, the painters following this need avoided the iconic reality of exaggerated illusionism and created a real iconicity. In my opinion this is the basic difference between naturalistic painting and Byzantine painting.

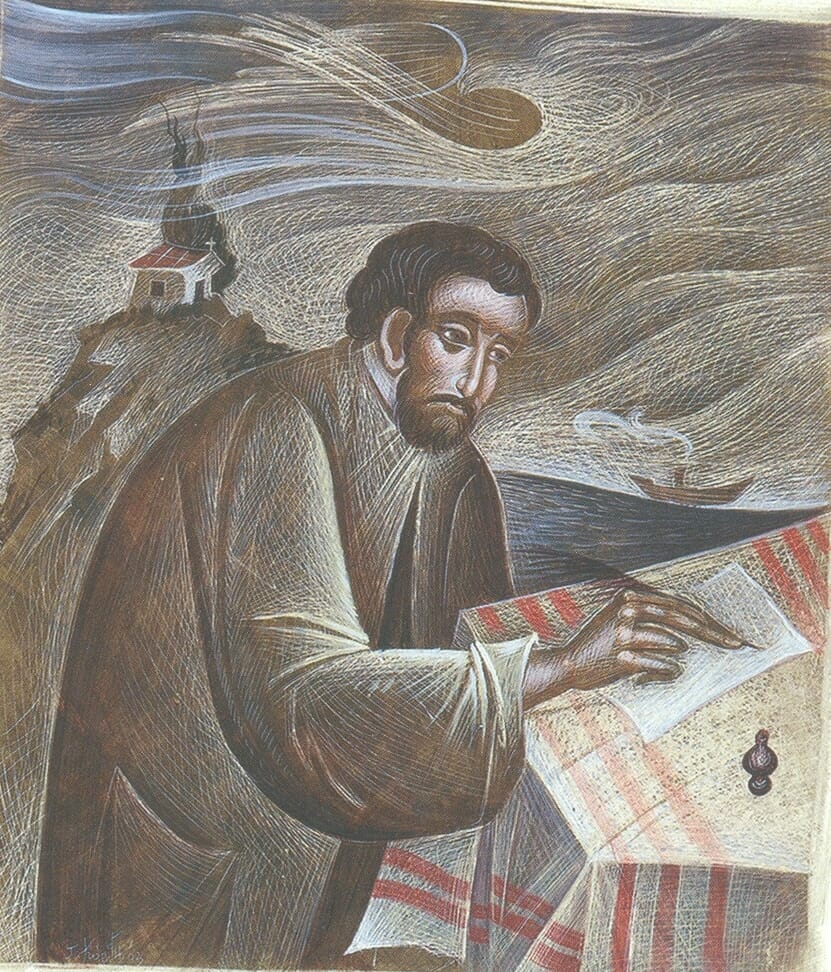

Fr. Silouan: It can be said that your non-liturgical work shows the creative use of various schools of painting of the early 20th century. For example, at times Vincent van Gogh comes to mind, then Fauvism and Expressionism, or the scuola metafisica of Giorgio de Chirico. Can it be said that these and other facets of 20th century painting have influenced, not only your non-liturgical work, but also your style as an iconographer? Are there lessons to be learned from the history of painting in the early 20th century that can be revalorized for our use as iconographers, without falling into the trap of willful innovation?

George Kordis: Western painting after Renaissance through Modernism is a great tradition of art and we as contemporary people participate in this willingly or not. So it is natural and legitimate to be influenced by this tradition and its great achievements. The only question for me is how to handle these achievements, in order for the continuation of the Orthodox Tradition to be achieved with no interruption. This is the only question. In order for this to be realized we as painters must be very careful. Any element taken from the secular painting must be appropriate and must be able to be assimilated in the previous tradition. For example, the impressionistic ideas on the use of color can be partially adopted by orthodox iconographers. The idea of using complementary colors as the impressionists used them is fine. But, we must not in any case loose the linear rendering of the highlights and the clearly defined shapes of the items depicted on icons. The foggy and shapeless forms in impressionistic painting is not appropriate for Byzantine painting. Another example, the strong pure Fauve colors are beautiful in a miniature painting and in this context we could use some combinations or colors from such a palette. But, in my opinion, we cannot use this palette in a Church wall painting, where the demand for a peaceful and serene atmosphere is predominant.

The use of elements from secular painting was always a common practice in Byzantine and post- byzantine period by all icon painters. So we must not be afraid of this. We simply have to be aware of the depth of our Tradition in order for the continuation and the enrichment to be achieved.

Fr. Silouan: We can perhaps speak, in general terms, of two major tendencies in the history of icon painting: classical and expressive. In the first can be seen the Greco-Roman or Hellenic sense of proportion and beauty, mainly leaning towards naturalism and a sense of corporeal solidity. Whereas the second leans more towards a kind of “abstraction,” graphic simplification, linearity, elongation, “distortion” and the flattening of forms. A third stylistic possibility would be the combination of these two extremes.Would it be incorrect to speak of your work as an “iconographic expressionism”?

George Kordis: It is true that in the past and in the frame work of Byzantine painting there were two trends, the one descending from Hellenistic naturalism, and the other one from the expressionism of Late Antiquity. But, these two trends were always mixed and there was a combination of elements from both traditions. So in Comnenean painting for example, which is mostly linear, there is no lack of the rendering of the volume and the expression of corporeality. And in Paleologian painting, where the rendering of the volume is predominant, the linearism is always present, since everything is rendered in closed and defined forms of colors. So, I believe that there is no such clear and sharp distinction between these two trends. Personally I am studying the entire tradition as a unity and I take elements from all stylistic trends and “schools”. The only thing that I am trying to do is to compose in the framework of Tradition and not to destroy the basic rules and principles. The icon must always be a presence of the person depicted. The person depicted must be immediately recognizable by the faithful people. The Icon must invade the reality of the spectators and crate an aesthetical bond with them. The spectators entering a painted church must feel the presence of the saints and have a taste of the qualities of Paradise.

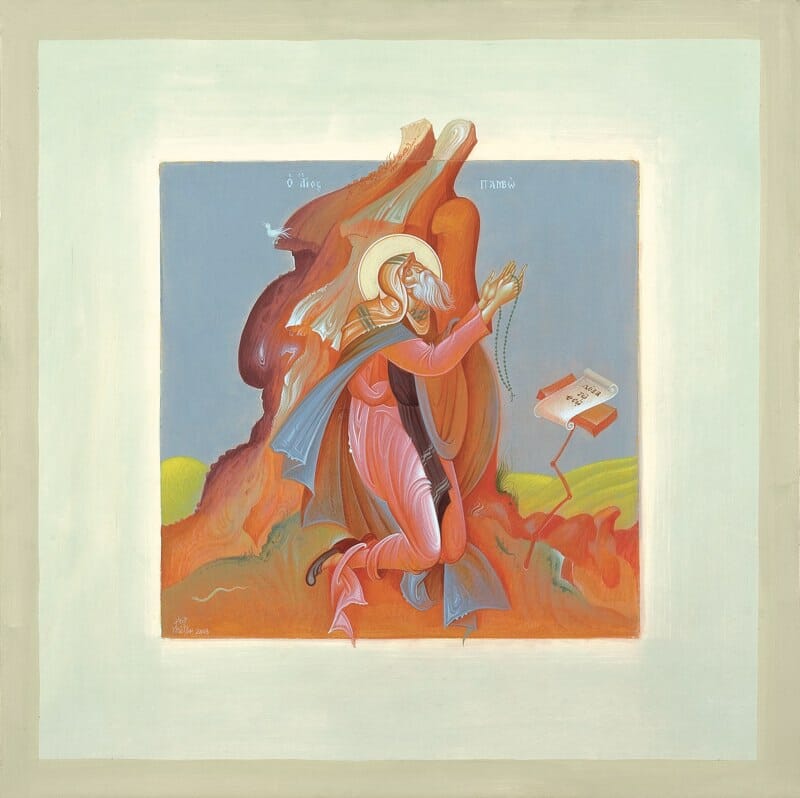

Fr. Silouan: In your work you do not simply copy the prototypes, but rather creatively interpret them, without in any way, it seems to me, compromising fidelity to Tradition. At times it appears as if you even arrive at prototypes not previously seen, but then again, in no way compromising Tradition. I’m reminded of a recent icon of “St. Paul’s Vision on the Road to Damascus,” and your older compositions of major events from the Gospel and the Fathers of the Philokalia. Some would make of the task of the iconographer a kind of academicism, a purely mechanical duplication of ossified forms, allowing no room for creative solutions to pictorial problems. Can you please elaborate on the seemingly paradoxical congruence between artistic creativity and fidelity to Tradition?

George Kordis: As I have already mentioned what I am trying to do is to follow Tradition and to work on its ground. The heart of Tradition is the only thing that matters. Unfortunately today many iconographers believe that Tradition is defined by some specific forms created in the past by great iconographers. This is not Tradition, but only expressions of Tradition in time. That is why we have schools, and trends in the past. Iconographers were aware of the reason behind the painting, they knew what they were looking for when they drew lines and used colors. That is why their painting, their icons, although they are not identical, are nevertheless united in the common ground of the principles and ideals. Tradition is always stable and changing. It always has these two characteristics, otherwise it is not Tradition. If Tradition stops creating it is not Tradition any more but a museum. Fidelity to Tradition means creating on the ground of its stable values and principles.

Fr. Silouan: I’ve noticed that you mainly work from memory. When you work on a composition on the walls of a church you don’t consult prototypes. There are no pictures or drawings around you that are used as reference. It seems to me as if you have memorized the prototypes and recall them as you work extemporaneously. This allows for spontaneous arrangement and compositional problem solving, based on the immediate architectural context. Consequently, in the end the composition breathes, it doesn’t appear contrived, forced to fit in without it being resolved fully, as it often happens when a canvas is painted according to measurements and then glued into place. The simple answer would be that this is a gift you have been given, but I’m sure you would agree that such a skill has not come without many years of experience and hard work. From what you have learned throughout the years, what advice would you give to an iconographer seeking to acquire this level of pictorial memorization?

George Kordis, Moses Encountering the Burning Bush. Preparatory drawing on a wall of the Fanerwmeni Church, Greece.

George Kordis: It is good to study the example of old icons before we start working, so we can be sure that there will be no dogmatic mistakes in our icons. But it is also important to start working form memory. In this way the icon painter works with a lot of freedom and from his heart. You keep in your mind the saint and the event, and you work praying more than trying to copy the forms. The icons in this way could be more spontaneous, more authentic. But it takes time and practice to become so skillful.

Fr. Silouan: As mentioned earlier, alongside of your iconographic work, you also engage in non-liturgical painting and drawing. There is a tendency to see these as mutually exclusive. Nevertheless, it seems to me as if your practice addresses the contemporary problem of an art world that has become disconnected from the Sacred. Therefore, in a way your secular work can be seen to function as a bridge, or “threshold,” through which contemporary man can be reminded of the immanence of the Sacred in spite of his suffering, as he searches for genuine communion in his fallen predicament. For perhaps the poetic images of embracing couples and melancholy lovers are nothing but personifications of our intense longing for union with God, in the spirit of the Song of Solomon. Even when the tone of the theme is tragic, speaks of isolation, and suffering rears its head, it does not seem to me to lack a redemptive side if seen within the complete body of your work. Taken as a whole the joy of life predominates in it. But these are my interpretations. What would you say is the main theme of your non-liturgical work? And how can non-secular art serve as a “threshold” to the mystery of the Sacred, in a culture that has forgotten of the sacramental function and potential of art as seen in the icon?

George Kordis: I like your approach. It is true that my “secular painting” is not really separated from sacred art. Orthodox Christians in the past used to render ecclesiastic and non-ecclesiastic themes in the same painting mode. So in Byzantine painting there are many themes describing everyday life or other themes in the same style as icons. The same ideals and principles are used to depict even pagan themes with the gods of Gentiles. Many such paintings are preserved especially in miniatures. My intention is to paint the different aspects of human life because the Orthodox Church embraces everything, even the “tragedy” of postmodern isolated people, who live without any reference to God. The use of the Byzantine painting mode is, I believe, the bridge that joins everything and gives the impression that even the fallen human reality is not excluded, that even there we find a flavor of the light of the Church. There is everywhere hope and depth.

Fr. Silouan: In the UK the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts offers a post graduate level course of study for icon painting with Aidan Hart. Also, in Greece, Russia and Romania professional icon painting programs can be found in Seminaries and Universities. Nevertheless, here in the US all we have are the weekly itinerant workshops that are geared more towards the “hobbyist” pursuit of iconography. How do you see this phenomenon? and what do you think needs to happen first, here in the US, before we see a professional school of iconography established for the training of future iconographers?

George Kordis: It is true that in the States there is no professional school for iconographers. There is no place where someone could be properly trained to become a skilled and good iconographer. Of course, around the Orthodox world there is always the problem of the method of teaching. Traveling and teaching around the world I have recognized that every iconographer uses different methods and actually improvises. This is a problem. Not because there are different methods but because usually these methods are not real ways to achieve the goal of teaching. In my opinion, first we have to work on establishing a good method of teaching, based on the ground of Tradition. A method that could help students become creators and not copyists. Then, a school of Icon painting could be established where experienced iconographers from all over the world could be invited to give their experience and knowledge. In this way we can hope that in the next few decades an American “school” of iconography could be established with its own characteristics and idioms. It is in my plans to start something like this and I am in contact with other iconographers and personalities working in the field of ecclesiastical arts that have the same vision. We hope that in the next two years this will happen.

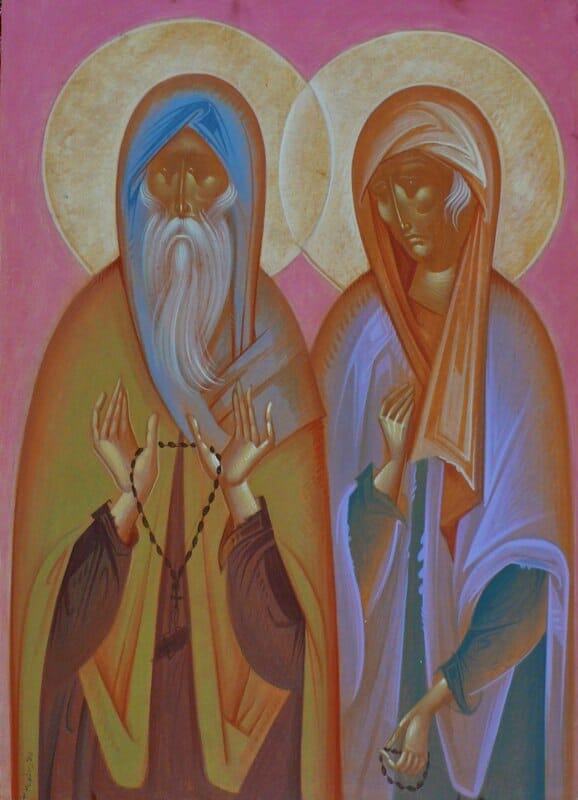

It is interesting to hear Kordis describe his own approach to icon painting. His words seem to describe a solidly traditional understanding of liturgical art. But can the same be said of his painting? There are some paintings by Kordis with which I am uncomfortable, such as the image of Sts. Andronikos and Athanasia shown here. The figures seem insubstantial – like ghosts, which I think is a big dogmatic problem. But I don’t know what is the purpose of this image. Does Kordis intend it to be used as a liturgical icon?

On the other hand, many of his icons, though unusual looking at first glance, do indeed have all the characteristics of the canonical style, and I must remind myself that in many ways they are less eccentric than the icons of Gregory Kroug, and even of some medieval masters. Whether or not one entirely likes Kordis’ icons, I think everyone should agree that it is healthy for gifted iconographers to occasionally push the envelope and experiment at the edge of canonical norms. Of course, most such experiments will not be wholly successful, but occasionally something new arises that has real merit and influences others, and this is how the tradition evolves.

The one thing in Kordis’ liturgical work that bothers me is the backgrounds with a gradation of color, as in the Columbia, SC church. I cannot think of a historic example that has this (though perhaps there is one of which I am unaware). It seems to me to be contrary to the idea that the background of an icon represents the uncreated light (which is intense, constant, and opaque). I would be very interested to hear Kordis’ explanation of why he does these gradated pastel backgrounds.

Hello Andrew,

That’s a good question Andrew. I’m not sure whether the Sts. Andronikos and Athanasia icon is intended for liturgical use. It might be for Kordis private use.

Also, if you notice, the icon bears no inscriptions, maybe it’s a work in progress. I chose the icon since, as you pointed out, it shows Kordis pushing the envelope.

Taking risks in icon painting is something rarely seen, accepted or understood today. Most seem to relegate Tradition to the notion of chronology, the repeating of things of the good-old-past without much thought about the creative use of principles. Although the aforementioned icon might not be wholly successful, it at least asks us to reconsider our presuppositions of what is traditionally possible.

In my opinion the figures do not appear ghostly. Rather they appear to have a transfigured corporeality. Luminosity permeates them in a way that is aesthetically convincing to me. Luminosity, light, is not depicted solely by means of tonal values, but mainly through color hue and saturation. Color illumines. Yet, they appear to be momentarily “darkened,” as when a flash of light suddenly shocks the eyes- darkness and light suddenly become one. In this way it dogmatically relates, although in an admittedly unusual way, to the theology of “divine darkness.” It can also be said that the saints here convey the dusk of old age, suddenly passing into the dawn of uncreated light. We’re dealing with the very moment of transfiguration. Notice the “negative highlights,” on the arms and the hood of St. Andronikos. It reminds us of how light passes through a lens and leaves behind the imprint of its presence on the film negative. The film negative in the camera can be seen as the body in the cave of creation, so to speak. These negative highlights suggest that we are not solely dealing with a natural light source; the saints are also imprinted by light coming from another, Heavenly dimension. This Light appears to be dark to the natural man, as St. Paul would say. So here we have an emphasis on transfigured corporeality- the resurrected body. Bear in mind that the disciples thought that Christ was a spirit, or ghost, when He walked on the sea and appeared to them after the Resurrection. Anyhow, that’s one way of interpreting the work in light of the theology of the icon. I don’t believe these observations are solely based on my likes or dislikes, or on what the icon is suppose to do without it actually communicating so aesthetically. I believe them to be objective, based on the evidence of the concrete aesthetic choices Kordis has made.

As to the question of gradated backgrounds, I admit that it’s difficult to find historical examples. The only ones I can think of are the Mstera icons of the 19th and early 20th century. Some might consider these icons as “decadent” in that they incorporate some naturalistic elements that tend to come across a bit romantic at times. Nevertheless, it seems to me that they generally maintain a grounding on Tradition. Only the background, the landscape and sky, are gradated. The rest of the image is Byzantine in flavor, linear, worked from within traditional principles. So the Mstera masters can be seen as another example of “pushing the envelope.” Another thing to remember are the frescoes of Dechani Monastery in Kosovo. There you will find gradation on the ground and rocks/mountains. At the bottom it is green, suggesting grass, and it gradually turns an ocher color, as to suggest the hue of stone.It would appear that the hesitation about gradated backgrounds comes from its association with bad examples of naturalistic, religious Western painting.

The issue seems to me mainly a matter of emphasis and attitude towards naturalistic orientation in icons. Naturalism as such is not the problem. The problem is: what kind of naturalism. What is it doing in the icon? Does it contribute, or not, to express a specific content. It would be dangerous to say that since we find no examples of gradated backgrounds then it is therefore banned. There is always a first time that is not contrary to Tradition. Naturalism interferes when it becomes excessively illusionistic and theatrical, sentimental, grossly corporeal, and when it compromises the picture plane. In short, when it fails to remind us that there is not only sense perception, but also an intelligible dimension to reality. Hence, if kept in check by abstraction, naturalism in fact can help to emphasize the incarnational theology of the icon. So a gradated background reminds me of how the skies in Nature, “declare the glory of God,” and how their unbelievable other-worldly hues are symbols of the heavenly reality perceived by the prophets in vision. Anyhow, Kordis’ use of gradated background is kept in check enough. Through their luminosity they do in fact convey the idea of uncreated light. They remind us of how the beauty of nature manifests uncreated Beauty. In the end, I think it’s a matter of seeing the uncreated light not solely as the impenetrable mystery that it is, hence an opaque background; but also encompassing a translucent, transfigurative side, in which even the coarsest of matter, Nature, becomes the garment of the Lord.

In Christ,

Fr. Silouan

Great article. I’ll put the link to this in my Art/Icon blog so my students can have access to it. We use Kordis’ book in our icon class.

Blessings,

Christine Hales

This man is incredibly blessed and talented. His work reminds me of Theophanes the Greek who painted in Russia back in the 14th and 15th centuries. What is old is new.

“You cannot step into the same river twice,” wrote Heraclitus.

It is impossible for us, living now, to have the same “Tradition” as the apostles, the early church, the Byzantine church, etc. Our very concepts of Tradition are artifacts of the Enlightenment and modernity. There is no escaping the fact that the past to which we try to remain faithful cannot is largely an artifact of our contemporary imagination.

This point was brought forcefully home to me when the Met Museum had a show of Byzantine art from the high point of the empire. The freedom displayed there would not be countenanced today. There are pillars of Orthodoxy today who were hardly significant in the Byzantine era, but have been made prominent by modern scholars who long for a past that never was.

Nor is it reasonable to think that the good news of the gospel has been fully expressed in any age or embraced with greater fervor and perfection, on the whole, by our ancestors than they are today.

We become a cult, in the particular modern sense, when we claim that the only way to portray the sacred in art is a certain tradition of Orthodox iconography. We have a great tradition of portraying the sacred in art. The Orthodox icon is getting global recognition, just as, say, the bagel, has escaped beyond Jewish culture. We do have a great and valuable tradition. But we do ourselves no favor when we put down all of Western art as divorced from the sacred. It is not true.

The only way that we can be faithful to tradition would, I suppose, to be as much a part of our time as the creators of the tradition were a part of their time, and to exercise the same creativity as those who went before us.

It is time for us to stop being both defensive and judgmental, and to give thanks for being born in the particular time and the particular places where God has chosen to place us in order to receive and share the flames of his love.

The comparison with Fr. Gregory Kroug is an intuitive one; both iconographers are very bold and unusual. They are brilliant masters of their craft and they both employ many elements of modern art. But Kroug’s sense of the icon never for one moment allows the form to interrupt the image’s transparency to the spirit, while in the icons by Kordis I have a hard time even seeing past the form. Kordis’ images give me an empty feeling, all these colors and forms seem like they should be leading me to the person depicted, but instead they lead back to themselves.

[…] few days ago I read an interesting interview with a contemporary Greek iconographer, George Kordis, “The Art of Icon Painting in a Postmodern World.” Several things caught my eye, the least of which wasn’t the style of this modern iconographer and […]

Andrew and Seraphim, I think bringing up Kroug is the right thing to do here. I really struggle with Kordis’ icons, but I don’t with Kroug. I took myself to task to figure out what it is about each that I either like or dislike and I come to the basic conclusion that Kroug is Russian, French and Modern, while Kordis is Greek, American and Post-Modern. Those different series of elements have natural affinities together, so in Kroug we have the natural “minimalism” of Novgorod icons merging with the early modern reduction we can find in the cubists but also in people like Maurice Denis. As for Kordis, we really have a form of mannerism that has affinities especially with the “transavangardia” painters of the 80s, think especially of the Italians like Sandro Chia or french artists like Gerard Garouste. And in that sense I wonder if there isn’t a bit of the post-modern irony in his work, that is the idea of the “commentary” which is mannerism. In this sense, his compositions, lines and colors would be a “memory” of iconographic conventions, memory truly in the sense of post-modern memory rather than patristic memory, memory that is already a commentary, memory that is something of caricature. For certain though, this interview is truly wonderful and it helps me to understand what he is trying to do and see his deep love of Tradition and reverence for the Saints. Also, anybody who has watched those videos of him sketching huge frescoes directly unto the surface without any preparatory drawings can only be amazed at how much he lives the language of the Icon.

That’s very insightful. You’re right that Kroug’s work is modernist and medievalist simultaneously, and yet un-self-conscious, and without irony. It seems impossible, but there were occasional instances of this a century ago. Two architects come to mind – Hendrik Petrus Berlage (Dutch) and Carlos Scarps (Italian) were contemporaries of Kroug, and they likewise worked in a modern Middle Ages so naturally that one wonders why architecture would ever be anything different when looking at their work.

Kordis’ work, on the other hand, seems to emphasize the tension between medieval and modern influences. If the tension resolves, it seems to do so because of the force of Kordis’ artistic will imposing a resolution. I suppose this is another way of saying that his mannerisms seem deliberate, self-conscious. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but perhaps it explains why it is easy to look at a Kroug without thinking about Kroug, but hard to look at a Kordis without being conscious of Kordis himself.

Nevertheless, I am glad for both of these eccentric iconographers. They are both so personal and virtuosic in their style that no one could really imitate them. But their work serves as valuable examples to ‘frame’ the edges of iconography, and to inspire students to understand the cannon more broadly.