Similar Posts

This is the seventh part of an ongoing serial (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6)

Among all the furnishings found in a church, lamps have always held a certain sacral honor. Saint John saw seven lamps standing before the throne of God. The vesperal hymn, Phos Hilarion, proclaims during the lighting of the lamps, “O Gladsome Light of the holy glory of the Immortal Father,” thus connecting the flame of the lamps to the uncreated light of God. Lamps stand partly in our world, casting useful light for the services, and partly in the realm of Divine Mystery. A lamp before an icon is a beacon of the light of heaven that shines on the living saint.

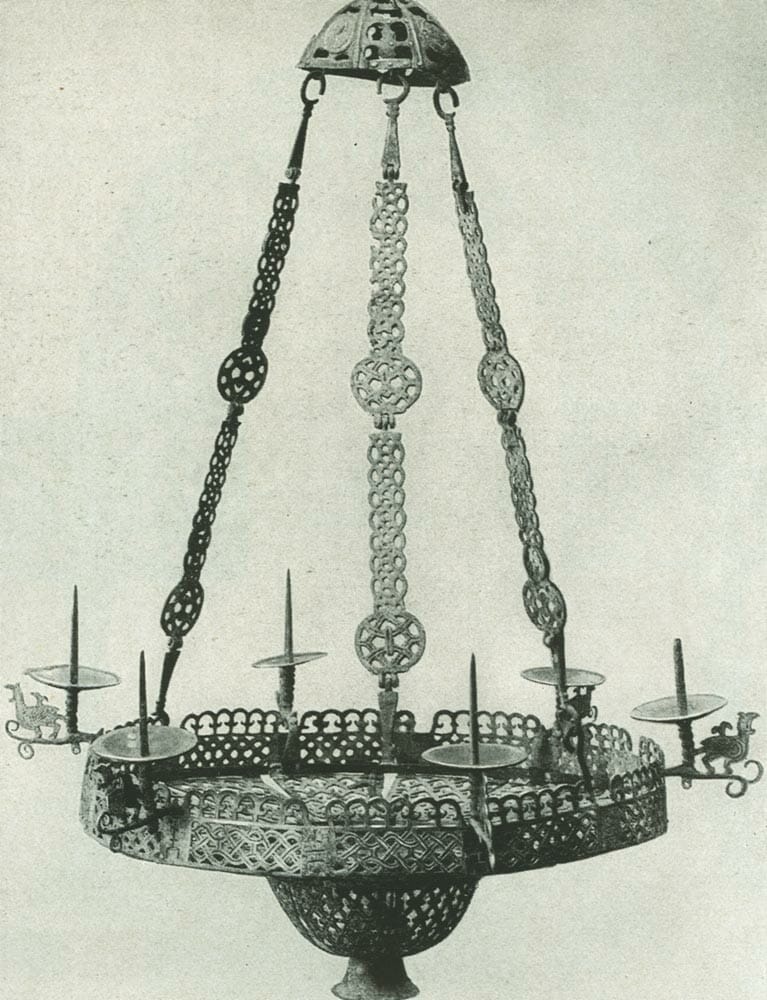

Often made of metal, lamps have a lightness and strength that furnishings of stone and wood do not share. Byzantine lamps were often cast bronze or silver with open cutwork ornamentation. Since the late Middle Ages, chandeliers have followed the European form of a brass globe surrounded by delicate arms. Not all lamps are hung; some stand on the floor supported on ornate turned-spindle shafts – an oriental and Islamic influence of great antiquity. All of these venerable styles share an enticing complexity that invites wonder and eludes understanding. Such mystical designs are well-suited to the lamp’s liminal character, for lamps seem to straddle the boundary between earth and heaven. Not wholly grounded in the earthy weightiness of wood or stone, the delicate and ornate metalwork reflects transfigured creation. In the hands of the best craftsmen, metal filigree and polished silver can have the simultaneous qualities of being prominent and sensual as a rich material, and also mysteriously vanishing and unreal.

The effect of lamps hanging in an Orthodox church is uniquely eastern. In most Western churches, chandeliers are very orderly and subservient to the architecture. But in an Orthodox church, lamps are all different shapes and styles, hanging anywhere and everywhere. The oldest and richest churches have accumulated collections of lamps so dense that it is hard to discern any pattern in how they are hung. But even in the churches that retain their original lighting design, such as Decani with its medieval choros, or St. Elijah, Yaroslavl, with its seventeenth-century chandeliers, the light fixtures have great prominence. A Byzantine choros dominates the spatial experience of the nave. All the volume of the church seems to revolve around it, a triumphant crown forever suspended just above the liturgy. And the early European chandeliers installed in old Russian churches were larger and more elaborate than those in the West, and hung right in front of the iconostasis.

Without electricity, the lighting of lamps constitutes a great drama, and this was always so. This is plain to see in the very structure of Vespers, with its ‘lamp-lighting psalms’ and Gladsome Light. In churches full of lamps, someone is continually tending them, moving ladders, lighting them, swinging them, extinguishing them. The richest lamps are reserved for feast days, and their use betokens a great celebration and victory. In such a church, anyone with open eyes is constantly aware of the needs of the lamps, and considerable resources are expended on keeping them fueled, tended, and polished.

When hung about ten or twelve feet above the floor, lamps and chandeliers come to resemble the starry firmament, which, compared to heaven painted above, is quite close to earth. This transparent ceiling of lamps magnifies the interior of the Church because by comparison the frescoed vaults above appear farther away. This is a simple optical effect, yet there is a mystical dimension as well, for the Church is truly a microcosm. The lamps are stars, and, to those with eyes to see, standing beneath them feels like standing outside, as though all the universe were contained in the temple, an infinite chalice holding all of creation.

Hanging lamps are augmented by just as many standing lamps. In important churches many tall candlesticks reach right up to the height of the chandeliers; others are low and accessible to the faithful, and, in a crowded church, they light the people more than the icons. There are special services during which all present hold a candle, each worshipper illuminated like an icon by a lampada. How beautiful, on Pascha night, to see the bright ocean of joyful faces glowing with the same light as the icons—a beauty that shines unexpectedly from the darkness, like the phosphorescence of a tropical sea. Truly, the darkness comprehendeth it not.

In a Turkish mosque there are a thousand identical lamps, all hung in orderly rows like the kneeling worshippers. But Orthodox churches are lit with a diversity of lamps like the diversity of saints. The chandeliers are the starry light of Heaven. They give honor to the saints and angels painted on the walls, who no longer have need of sun or moon for their light. The lampadas before the icons reveal the inner light of each saint, their uncreated radiance. The gilded icons work like reflectors for the lampadas, like old-fashioned wall sconces with mirrored backs; they reflect the lamplight back into the whole church, just as the radiance of the saints shines into the whole world and illumines all. Finally, the candlestands reveal the piety of the faithful. Each candle signifies a prayer, and the light of that candle, illuminating those who stand near, shows the inner radiance that is wrought by prayer.

Lamps must be elegant and mystical in their design. Light and delicate, but intensely beautiful, they must resemble the flames they bear. Many styles and materials can work well for lamps, but there must be no hint of heaviness. In the 19th century, Russian lamp design moved away from the traditional ethos. Chandeliers became so heavy and their shape so mountainous that they elicit distraction and concern about the strength of their mountings! Standing candlesticks may have retained the traditional spindle shaft, but they grew so fat and imposing as to appear immoveable. By their appearance, such lamps speak a false doctrine, one of bourgeois ostentation, rather than mystical beauty.

A modern church chandelier of ponderous and imposing form, modelled on 19th-century Russian palace fixtures

In our own day, cheap lampadas and candelabra are mass-produced in stamped tin with tawdry, fake gemstones. Such disappointing details expose the physicality of the lamp – a distracting effect quite unlike that of the elegant silverwork. Worse yet, faux materials introduce an element of untruth into the visual message of the lamps. These lamps are an imitation of the treasures of our church’s imperial past, the product of a misguided nostalgia. People delight in these obvious fakes because they are unwilling to pay for things truly fine, and are afraid to confront the artistic reality of our church’s limited wealth.

Good lamps need not be expensive, and they not need even be metal. Historically, they were sometimes made of wood to great effect. Candlesticks can be very gracious in turned wood, and there are some very old choros chandeliers made of carved and inlaid wood that rival the lightness of metal. Regardless of material, they should be true to their nature, and not falsely imitate a finer craft.

[…] Icon of the Kingdom of God: The Integrated Expression of all the Liturgical Arts – Part 7: Lamps https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/an-icon-of-the-kingdom-of-god-the-integrated-expression-of-all-th…Monday, Dec 31st 5:05 pmclick to expand…orthopraxis said: I don’t understand the purpose of […]