Similar Posts

This is the fifith part of an ongoing serial (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4)

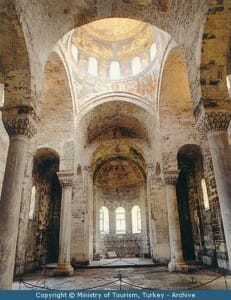

The marble-clad walls of a Byzantine church are glorious and majestic when glimpsed between icon stands and chandeliers during a crowded, smoky service. But all alone, in an empty, ruinous church, the rich architectural materials can suggest the forbidding formality of a marble bank lobby. A Church, like a home, needs furniture. Without hanging lamps, the domes and vaults are too close and too plain – impressive, ponderous, but not mysterious. In the absence of organic materials like wood and silk, the eternal stillness of the architecture seems more sepulchral than sacred.

History has not been kind to our heritage, and moveable furnishings have suffered perhaps more than anything else in our tradition. In too many places, the famous ancient monuments of Orthodoxy have been stripped bare by the ravages of time. And the impoverished history of Orthodox art and architecture in America has done little to replace in the New World what has been lost in the Old. American Orthodox lack even a basic understanding of the vital role liturgical furnishings play in giving our churches their proper ethos.

Thus we must give close attention to those precious few churches that have not been sacked by thieves, burned by armies, or remodeled by subsequent wealth. The best examples are the churches on Mt. Athos, the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mt. Sinai, Visoki Decani in Kosovo, Holy Trinity Cathedral at Sergiev Posad, and St. Elijah the Prophet in Yaroslavl. These churches, though spanning a millennium in their construction dates and containing furnishings of many periods, have a furnished effect which is wholly traditional. They look the way Orthodox churches always looked. It is truly a miracle that even these few examples survive, for as easy as it is to steal or burn these treasures, it is even easier to discard and forget them in the waves of fashion. In the time of Catherine the Great, nearly all medieval iconostases and furniture were replaced by baroque appointments. Multitudes of lamps and shrines were swept away by the austere taste of Neoclassicism. In our own age too, the modern, practical mind proves similarly reluctant to clutter the pristine space of a nave with costly shrines and treasures.

So what do we learn from these few surviving exemplars? Firstly, Orthodox churches were absolutely packed with furnishings. The walls and piers are so dense with shrines and stasidia that the lower walls can hardly be seen. The vaults are hung with so many lamps that they almost form a second ceiling not far above the floor. The nave is crowded with as much furniture as people – icon stands, lecterns, candlesticks, sometimes even tombs.

Now to the modern mind it is illogical for frescoes to be obstructed with seldom-used lamps. The nave is for people, not furniture, and frescoes are meant to be seen, not hidden. And so many prominent shrines must distract one’s visual attention from what should be the focus of corporate worship: the altar. Yet it is clear that in the past, Orthodox Christians saw no problem with layering lamps in front of icons, taking up floor space in small churches with furniture, and promoting personal veneration of shrines within churches. In ancient churches, many fresco compositions are so high and dimly lit that they can barely be seen, let alone identified. Yet it would not have occurred to the medieval mind to regret this. What was important was that the icon was present. It was less important that it be seen and understood. The presence of the icon signified the presence of the saint or event in the temple, and its very presence sanctified the space. The medieval Christian rejoiced in shrines and treasures. Every donated candlestick represented an act of piety for the glory of God. Every shrine was honored as though the saint himself were there. Despite the modern liturgical movement’s emphasis on corporate worship, in this medieval mindset, the unity of the Body is more perceptibly real to each worshipper than his own individual experience.

This attitude began to be dismantled with the influence of baroque art. In the eighteenth century, the liturgical experience became theatrical. Liturgical art was meant to be seen by as many people as possible and only from a certain direction, like a stage set. Churches were designed to look overwhelmingly dramatic, and architectural ornamentation took precedence over iconography and furnishings in the visual experience. At the height of Russian Baroque, the iconostasis became a writhing mass of gilded architecture, and the icons became sensational vignettes of emotional drama. With this aesthetic, the real presence of the Kingdom of God is suppressed, and religion as performance takes its place. The addition of pews to our American churches completes the transformation into a theatre. The result is the unconscious adoption of a new anthropology: an artificial division between spectators (laity) and actors (clergy).

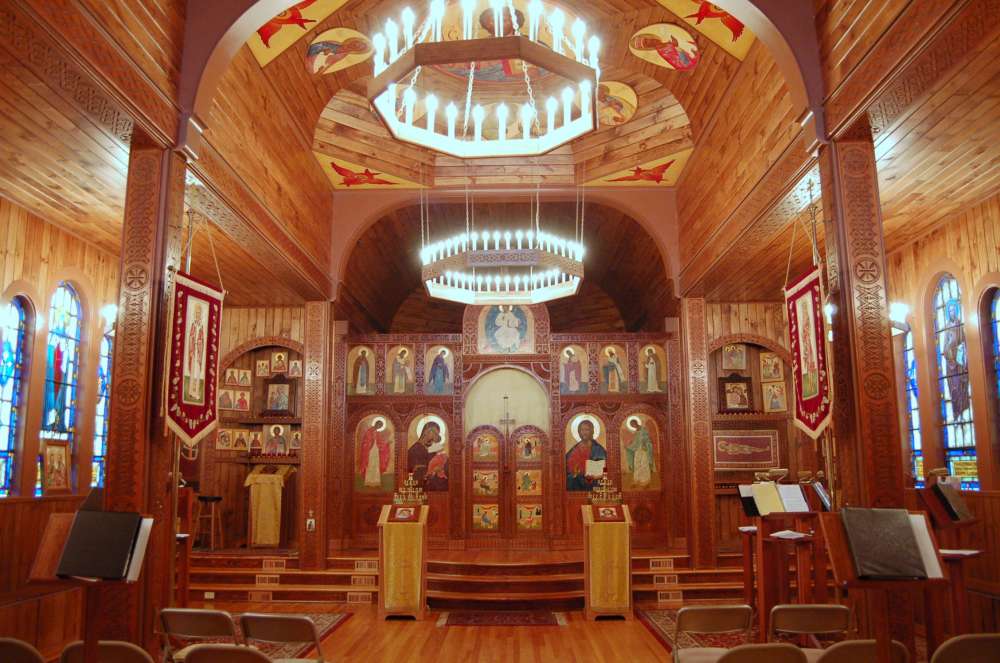

Today, even churches that have overcome the temptation of pews still succumb to the theatrical mindset in other details. Iconostases usually look good only from the front. Within the altar, and behind choir stands, clutter and ugliness is tolerated that would not be allowed to be seen in the nave. And the visibility of icons is considered so important that people sometimes hang lampadas beside the icons instead of in front of them, thereby rendering ineffective their purpose of lighting the icon. In a traditional church, liturgical furniture is distributed about the nave. Analoi, shrines, and candlestands are found in any corner, because the whole church is liturgical space, and any corner of the nave may be the site of devotions.

We must tirelessly battle against the theatrical spirit of the age that defines itself in sloth, entertainment, and artifice. The presence in our churches and homes of lovely, handmade objects is meant inspire us to be beautiful creations ourselves. Each work of art in the church must be conceived as intrinsically sacred, not a mere prop in an Orthodox stage set. The iconostasis must be beautifully built like fine furniture, not superficially ornamented on one side. Furniture needs to be solid and traditional, not plywood boxes with applied crosses. Like architecture, furnishings glorify God by the strength of their design and beauty of their craftsmanship.

The next several parts of this essay will explore furniture, lamps, vestments, linens, ceremonial implements, gardens, and incense in greater detail.

[…] the Kingdom of God: The Integrated Expression of all the Liturgical Arts – Part 5: The Minor Arts https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/an-icon-of-the-kingdom-of-god-the-integrated-expression-of-all-th…Friday, Oct 19th 9:55 amclick to expand…I think it’s important that everyone takes note of […]

Well said, Andrew … ”We must tirelessly battle against the theatrical spirit of the age that defines itself in sloth, entertainment, and artifice. The presence in our churches and homes of lovely, handmade objects is meant inspire us to be beautiful creations ourselves.”

Beautiful article. And I greatly appreciate the participation of Ksenia Pokrovsky and Anna Gouriev.

I am very happy to have discovered this site. May your work be blessed.

In Christ,

+ Paul

[…] An Icon of the Kingdom of God: The Integrated Expression of all the Liturgical Arts – Part 6: Furniture November 30, 2012By Andrew GouldThis is the sixth part of an ongoing serial (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5) […]

[…] 2012By Andrew GouldThis is the seventh part of an ongoing serial (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6) A constellation of lamps at Vatopedi, Mt. […]