Similar Posts

Just as the Ass and the Ox, the cave portrayed in the nativity icon is not specifically mentioned in Scripture as being the birthplace of Christ. In fact, St-Luke’s account does not say exactly where Christ was born, only that The Holy Virgin lay him in a manger. So why a cave? Why not a little stable building as in later European nativity scenes?

Icon of the Nativity carved in linden by Jonathan Pageau

Much of the typology of the nativity comes from the Protoevangelium of James though St-Justin Martyr also mentions this detail about the Birth of Christ1. Yet beyond the historical traces of this tradition, there are also very important reasons why a cave is Christ’s birthplace.

If we look at how the cave is portrayed in the Bible, we will find steadiness and coherence in its function. The cave is the ultimate protection, a hidden place within the earth in which people can find refuge against extreme hostility. This hostility can be one of general desolation, such as when Obadiah hid 100 prophets in a cave to protect them from King Ahab and Jezebel in the time of Elijah2. We see this also in Elijah’s own moment of refuge in a cave3. The cave can also be a place of hiding from adversity, as when David hid in a cave while king Saul was hunting for him4. In fact David’s cave is called Adullam, which means refuge.

On a more surprising note, the cave also acts as a protection from God himself, as when Moses hid in “the cleft in the Rock” to avoid the face of God’s glory5. In the same manner, Elijah runs to the opening of his cave when hearing “the quiet voice of God”6. This desire to be protected from God by the cave can take on the extreme as we see in the book of Revelations:

“the kings of the earth, and the great men, and the rich men, and the chief captains, and the mighty men, and every bondman, and every free man, hid themselves in the dens and in the rocks of the mountains; And said to the mountains and rocks, Fall on us, and hide us from the face of him that sitteth on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb7”

In this movement of all men to the caves, in this ultimate desire of all to be hidden from the wrath of God, we find the cosmic finality of that first gesture of Adam and Eve hiding themselves from God in the garden. This gesture of hiding led to receiving their garments of skin from God, a subject I have expounded again and again. And so in an important way, the cave takes on the double movement of periphery exemplified by the garment of skins, as both death and the protection of death, this corporal animal existence which envelops, protecting all while obscuring the divine spark hidden within us. And just as our dead skins are animal skins, if we notice how the cave in which Christ is born is a stable, we already begin to see how animality is related to the cave. We see this also in Daniel’s lion’s den, or more obliquely in Jonah’s fish or Noah’s ark, images so prominent in the catacombs in showing the mystery of death and resurrection.

- Daniel in the lion’s den from the catacombs

- Jonah’s fish from the catacombs

- Noah’s ark from the Catacombs

But as related directly to the garments of skins themselves, we see the strongest relation in Elijah’s theophany mentioned above. For as he ran to the mouth of the cave, hearing God in the “quiet voice”, Elijah put his mantle, his garment of skin around his face. We are therefore called to remember as well that after Mose’s experience in the cleft, he also covered his face with a veil, though now to protect others from his own glorious appearance.

There are more of these general relations between death, cave and garment. An example can be found in the story of Jeremiah, who having been lowered into an empty cistern to die, was pulled out by an Ethiopian with rotten rags9. But in the end, the strongest of these relations is in the story of David and Saul. One thing I rarely see commented on is how one of the meanings of the name Saul is “death” (sheol). This connection of Saul to death can be found not only in his name, but everywhere in his story, from his use of necromancy, to his desire to kill David, to the constant relation between Saul, David and garments. Saul wants David to wear his armour (his shell) when facing Goliath10, David receives the garments and armor of Saul’s son11. Saul also “pins” David to the wall with his spear by David’s garments12. Each of these examples would need to be expounded somewhere else, but for our subject we must come to the cave. At this point of David’s story, he has become an outlaw and has assembled 400 misfits, debtors, refugees as his army in a cave13. While they are hiding, King Saul comes by and goes into the cave to “cover his feet”, an expression used for defecating. As King Saul is doing his business, David cuts off a piece of his outer garment, which he then brandishes to Saul once Saul has left the cave, the token by which Saul lets David go for the moment. A more powerful image of the double movement of death could scarcely be found. David is already associating himself with all that is peripheral in society: malcontents, fugitives, thieves, what we could call his own “animals” in the cave. Then Death comes in through an act which is the very image of putrefaction, residue and the end of corporality. But David, the true yet hidden king, takes a piece of this process (as he is already doing by rallying this army of rabble) and uses it to save himself from Death. The story in the cave becomes a condensation of the entire time between David’s secret anointing and his ascension to the throne14. In the Psalm David wrote while in the cave we see some of this come through:

My soul is among lions:

and I lie even among them that are set on fire,

even the sons of men,

whose teeth are spears and arrows,

and their tongue a sharp sword…… They have prepared a net for my steps;

my soul is bowed down: they have digged a pit before me.

into the midst whereof they are fallen themselves…15

This use of the cave as death protecting from death continues into the traditions of the Church and can be found in several saint’s stories. I will just mention two. The first is St-Thekla, who when fleeing from men bent on molesting her, sees a cleft open in the rock. She enters to be saved from her assailants, but also to die.

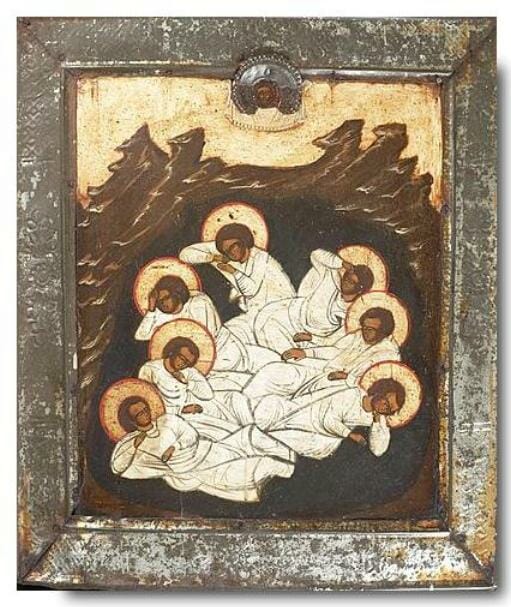

The other which resembles much Obadiah’s preserving the prophets in a cave during a time of Jezebel, is the story of the 7 sleepers of Ephesus. These youths hid themselves in a cave during a time of persecution against Christians. In this cave they fell asleep, only to awaken many years later when the persecution had ceased16.

So as we return to the icon of the Nativity, we will not be surprised that many have seen the shape of the manger in the cave as that of a sarcophagus or an altar. Here the very first revealing of the incarnation of Christ is already shown as an entry into death by the very taking on of flesh, the hiding of Christ’s divinity in Adam’s garments of skin. Through these associations, many mysteries come to the fore.

As we look at the cave in the icon of the Nativity, we are called upon to recall the two other icons of Christ’s life which happen underground, that is Christ’s baptism and his descent into Hades. Both of these are images of Christ’s descent into death, into chaos and transforming them into life. There are even recent images of Christ’s Baptism where he seems to be standing on the same doors of hell found in the icon of the descent into Hades, and so in a way these three icons are joined together in showing us the profound meaning of the incarnation.

Icon of Descent into Hades carved in Linden by Jonathan Pageau

And so although the cave is the image of death, it is not only an image of death, but also an image of that space within death, that opening of sacred space which contains the hidden treasure. It is the heart, the monk’s cell, the holy of holies all at once. It is the place at the bottom of the baptismal font where we shed in fact death though we are immersed in it, where is found that seed, that divine spark which can then transform death into glory.

I said at the beginning that the cave is a place where we find refuge from extreme hostility. What hostility was so prominent in the time of Christ that he should be born in a cave? The answer is Rome17. Rome had taken Israel, Romans would be the executioners of Christ, Romans would attempt to place foreign gods in the Holy of Holies, Romans would annihilate Jerusalem and would persecute the Church. But that child, that divine child born in a cave, who having later descended into the deep and having spent 3 days in death in order to conquer it, who’s followers would then endure 3 centuries of death and persecution, that same child would finally conquer the Roman Empire and transform the very scourge of his body into the very cradle of his glory.

————————————————————————————————-

1. Dialogue with Trypho, chapt. LXXVIII

2. 1 Kings 18:4

3. 1 Kings 19

4. 1 Samuel 22

5. Exodus 33

6. 1 Kings 19: 13

7. Revelations 6: 16

9. Jeremiah 38

10. 1 Samuel 17

11. 1 Samuel 18

12. 1 Samuel 19: 10

13. The story can be found in 1 Samuel 24

14. We should also keep this notion of Saul as Death in mind when we read the New Testament to discover that St-Paul was also called Saul when persecuting Christ. Saint Paul is also from the tribe of Benjamin, just like King Saul. This second Saul even kept “at his feet”, the garments of those who stoned St-Steven, the first martyr (Acts 7: 58). I always imagine those garments “covering his feet”.

15. Psalm 57

16. In some versions of the story, for example in the version which ended up in the Coran, there is also a dog which protects the sleepers in the cave. Those who have read my articles on St-Christopher might find this detail interesting.

17. It seems there is also another less obvious sign of the widespread desolation in the nativity text of Luke, though this one is more difficult to see at first glance. It is said that Augustus called for a census of the whole world. Although this might be one of the most difficult things for the modern mind to grasp, in the Old Testament a census is a very dangerous thing to do. God warns Moses that whenever a census is taken, an offering must be given to God, an atonement for the census. Without this, plague will strike, and we see this type of plague in the story of David when he takes a census (2 Samuel 24,). In this sense we could say that Augustus’ WORLDWIDE census had created a very dangerous situation. This of course might seem like the craziest thing to a modern person who cannot conceive of such things, but quantification is a mode of “fixing”, like King Saul trying to pin David to the wall. And we should not be surprised that many of the woes of the modern world might be related to our obsession of counting, calculating, accounting, in brief our desire to fully “fix” the entire cosmos which has a tendency to wiggle, react and fight our controlling hands.

Not to take anything from the danger inherent in Rome’s worldwide census, the more immediate threat to the newborn King was from the old king of Judea, Herod, who embodies the old man clinging to his garments of skin for protection from rivals. Anthropologically, kings first embodied cosmic vitality, and would be violently replaced the moment they weren’t strong enough to fend off rivals. This was even ritualized in the sacrifice of the old king at the end of the year to make way for a fresh one to start the new year on the right foot, in the endless cycle of life organized around death and violence. Traces of this universal paradigm abound, from Babylon to the folkloric practices of the Twelve Days of Christmas and of Carnival, involving social inversion, scapegoating and the selection by chance of a new king. Except this one is not out to take power in replacement of another; it is power that is afraid to lose its grip with the very idea of hanging on to it. So the old, fearful king, embodying the mortal old man in a climactic struggle against the new dispensation, lashes out desperately against every newborn in sight, in a vain, bloody attempt to get to the very principle of a new Life which, assuming death, has no part in the endless annual competition to fend it off a little longer, but is a threat to those who take it seriously. For this king not of this world is not afraid to make himself vulnerable and taking provisional shelter in its darkest places and shady company, of the kind that are shunned by someone who clings to life and is therefore ruled by death.

I think you are of course right in associating King Herod to Saul, an association that is quite obvious by his desire to kill Christ. We could also call him a kind of “reverse Pharaoh” who kills children, forcing the messiah to find refuge in Egypt. But even in Herod there is a bit of a mystery regarding this. Herod was crowned King of the Jews by Augustus, he was a usurper and established a new dynasty. Not only that, but he was an Edomite, something that is often missed. And if one knows a bit about Jewish Tradition, one will know that Esau/Edom= Rome. So although he was a religious Jew, he remains intensely connected to Rome as their patsy.

In fact, even David himself is seen as a “corrected Edom”. David is “Ruddy” (Edom) when Samuel first encounters him. The 400 renegades of the cave of Adullam (Sam 22:2) are seen to represent the 400 men of Esau (Gen 32:6). So again, the enemy of Israel-Jacob (which is Rome-Edom) becomes his garment. Jacob wears the skins of a goat to resemble his brother Esau: “the voice of Jacob with the hands of Esau” (Gen 27:22).

O God,

You have made death itself the gateway to Eternal Life

Look with love on our sisters and brothers

and make them one with Your Son’s suffering and death

so that sealed with the Blood of Christ they may come before You

free from sin.

Thanks for this and your previous articles, especially the St. Christopher series.

From an architectural perspective- I once observed that both the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem in and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem consist of grand structures positioned over holes in the ground. There is a certain formal irony in that, but also it is slightly counter to the conventional wisdom about the Judeo-Christian world view, of a transcendent, sky-god YHWH. But Christ emerges form the earth, returns there, and emerges again, before ever heading off into the sky. The incarnation is ‘earthy’ in that way, it seems. Humanity and all of creation are imbued with the divine very clearly– incarnation is not an alien visitation but an emergence of something innate to creation.

Thank you for your comment and your insight. Although I can understand that you would find this symbolism surprising, I think it is no more surprising than a tree coming from a seed planted in the ground, or from all of Israel’s connection to the divine life through a hidden glory residing on the ark in the holy of holies. Heaven appears on earth as a seed or even better as the kernel of a seed hidden in the fruit, in the core, in the husk of the seed itself. Hopefully that makes sense. And the incarnation, like all life (though in all ways being its pinnacle) is a marriage of Heaven and Earth and comes from a union of the two.