Similar Posts

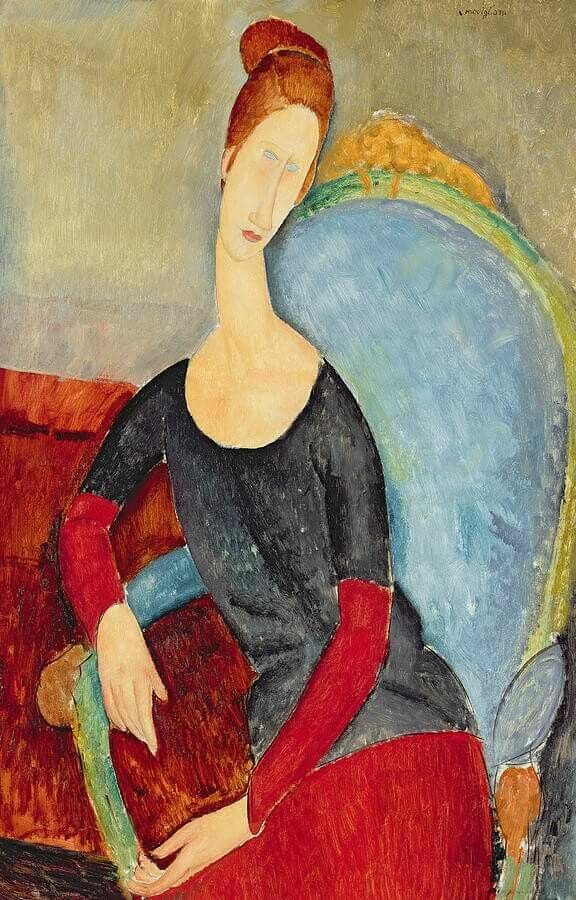

St. John the Evangelist, by El Greco, between 1610-14.

Oil on canvas, 97 cm x 77 cm. El Greco Museum, Toledo.

Participation Vs. Mannerism

As mentioned earlier, I take stylization as a neutral, unavoidable trait of painting at large and in fact of all made things. Any embodied articulation of meaning possesses a style. Style is a visual rhetoric of sorts. But not all rhetoric has the same power. The goal should be to “…move, in order to convince.” To effectively move the viewer, the heart of the painter must first itself be moved by agapeic communion. In other words, convincing pictorial articulation, synthesizing thought and feeling, should result from participation in the mysterious depths of that which is depicted, as you’ve pointed out before. Participation imparts authority to the aesthetic voice. Thereby style can become, in conjunction with enargeia[i], an ontophanic[ii] event, in so far as this is pictorially possible. Not an easy task, for sure, since there are no ready-made formulas to arrive at its accomplishment, but that is the point. How do we tap into the depth of what you’ve called the “exuberant actuality” of beings and announce their deified glory? In the end it is a gift of grace. Each person must speak from his or her own authentic voice of participation in conjunction with the spirit, rather than the letter of tradition. When style lacks participation, it devolves from manner to “mannerism”, lacking in depth, a surface effect: style for its own sake, mere gesticulation—uncompelling rhetoric.

We can discern two forms of mannerisms in contemporary icon painting which at times can overlap. The first comes as a kind of completely unengaged conformity to received prototypes, resulting in lifeless decorativeness, icons as duplicating icons or, as you have said, style as the “icon within icons.” I see this kind of mannerism—partly symptomatic of a desire to emulate the anonymity of the medieval painters, in an attempt to safeguard strict adherence to tradition—as ironically converging with the post-modern notion of the “death of the author.” The painter is expected to become a duplicator of past glories, to suppress his authorial signature, to have no personality. It can be seen as a post-modern disruption with the past without a sense of living continuity with it. It is a form of amnesia, a forgetting of the fact that tradition witnesses to variety of styles rather than monotonous uniformity. It is as if some inadvertently end up promoting tradition as the passing down of specimens in formaldehyde, rather than as ever renewing life and creativity, in harmony with the phronema of the Church.

In the second kind of mannerism, rather than the suppression of authorship, we find a more deliberate, self-conscious and sophisticated approach, in the pursuit of an authentic personal statement. When detected in a painter it has been described as the “commentary” of historical iconographic motives, “memory” as commentary of conventions, resulting in a kind of caricature of the icon. Some might see this as a post-modern orientation of ironic and cynical aesthetic play. But, in my view, commentary and aesthetic play need not always be seen as a negative thing. It is a matter of overall effect. Commentary and memory are hardly unavoidable. As I said earlier, the painter is always in conversation within a historical horizon. In its worst this mannerism falls apart into a cacophony of unresolved pastiche effects, as we’ve discussed before. Yet, in some instances a strong pictorial synthesis is accomplished which betrays indisputable and admirable virtuosity and mastery. Moreover, it can at times also be seen as engaging aspects of modern painting and even come with a transcultural component, appropriating features from a variety of painting traditions. This approach has the potential of striking the right balance without being liturgically disruptive in its innovations.

This leads me to introduce a caveat: not all mannerisms are utterly empty. Mannerism comes in various degrees of expressive power. Yes, they can be eccentric, but a bit of the idiosyncratic is not always to be shunned. Doesn’t the Gospel of St. John the Theologian stand apart, after all, in its manner of expression. His manner can perhaps be called a mannerism in light of the other Gospel authors, but not in a pejorative sense. His mannerism is full of participatory power—lofty mysticism. This is what makes his style unique, he’s a mannerist par excellence, and therefore so important. Maybe I’ve gone too far with my own mannerism. But what I’m basically saying is that at times a mannerist work can in fact betray participation, which is also a matter of degrees. Indeed, mannerism and participation are not always mutually exclusive. It all depends on the individual work, whether it works as a cohesive totality, where the forms and colors refer not only to themselves, but rather lead us back to the mysterious depth of the person and subject depicted, without leaving us feeling empty, where form becomes an event—a manifestation.

So, I must confess, while I may recoil from some mannerisms in icon painting, there is another kind of mannerism that fascinates me, in spite of its obvious problems. I guess that the “formalist” painter in me tends to be captivated by its penchant for virtuosity, gracefulness and excessive refinement. Traits that have often been disparaged in this style, but which in the hand of the right painter can have considerable expressive power. This mannerism can be seen as a way of channeling aesthetic play and intense feeling in an otherwise stifling conventional context. It emerges when the repetitious strictures of received conventions are felt as having run their course—whether these be in the standards of harmonious composition, canons of beauty or resemblance to nature. It denotes a desire for a new, more deliberate and self-conscious, stylization. It is the bending and stretching of pictorial standards, right up to the point of them almost snapping. This begins to sound, in fact, a bit like the second version just described of mannerism in contemporary icon painting.

Madonna of the Long Neck, by Parmigianino, 1535-40.

Oil on wood, 85 in x 52 in. Uffizi, Florence. This painting might at first glance seem unquestionably excessive and completely unrelated to the iconographic tradition in its expressive deformation. However, when compared with the icon below, it could be said that the two paintings parallel each other in their mannerisms, in particular in the idiosyncratic and elongated treatment of the figures.

Carmignano Visitation, by Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci), c.1528-1530.

Oil on wood panel, 80 in x 61 in. Propositura dei Santi Michele e Francesco, Carmignano.

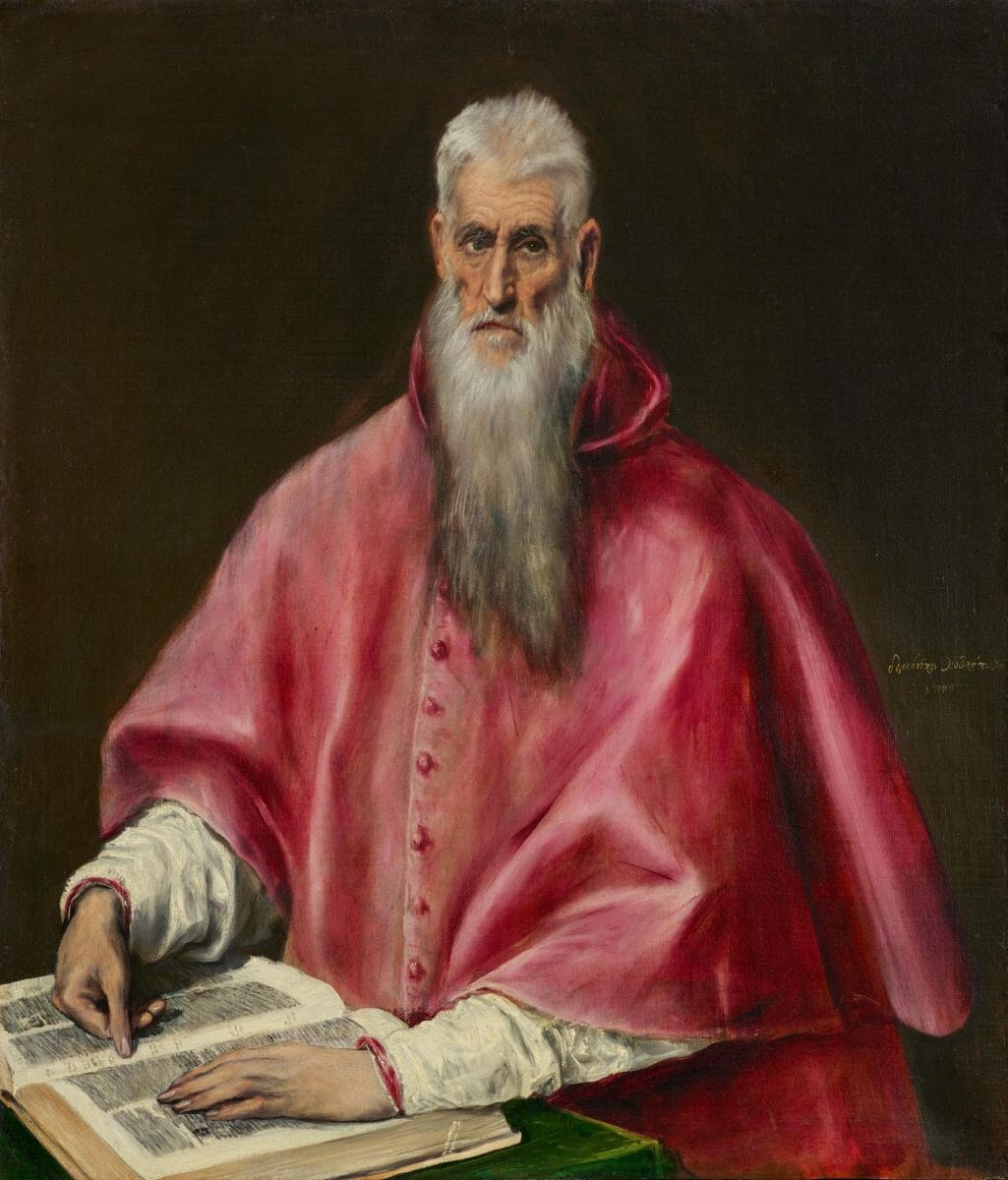

What I actually have in mind, however, is the historical Mannerism[iii] of the later High Renaissance, which arose in the wake of Michelangelo’s influence in Italy to become an international style, roughly emerging from 1520 and lasting until the end of the 16th century. This has led me to reconsider how the works of the Italian Mannerists, such as Parmigianino and Pontormo, might converge, in spite of the clear differences, with aspects of icon painting. Perhaps they can offer clues in the treatment of color and the elongated figure. But we should not forget El Greco, who also falls within this period and serves as a bridge, so to speak, if not a synthesis, between the Byzantine icon and the Renaissance painting traditions. Pondering on this historical phenomenon, as it touches on the more general issue of style, has made me wonder if perhaps there is a parallel between its cultural climate and our current predicament in icon painting. Are we in a Mannerist stage in the history of icon painting?

Giovanni della Casa, by Pontormo, 1542-46. Oil on panel, 102 cm x 79 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington.

St. Jerome, by El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos), ca. 1590–1600.

Oil on canvas, 43 1/2 in x 37 1/2 in. The Frick Collection, NY

Be that as it may, it goes without saying that the use of elongation within icon painting has to strike the cord of pious exaltation and gracefulness without falling into sentimental and indecorous sensuousness, as it is often the case with Italian and Northern Mannerism. As with anything, there is good and bad elongation. Elongation does not guarantee aesthetic vitality and spiritual profundity in an icon. With the icon the challenge is to elongate without falling into the trap of excessive artificiality and the obviously ridiculous. Although it is often the case that any kind of distortion and exaggeration tends towards the eccentric, I don’t really mind if it’s paradoxically accompanied by a sense of gracefulness and elegance.

Sts. Mary of Egypt & Zosimas, by Fr. Silouan Justiniano, 2016.

Egg tempera and gold on gessoed panel, 11 in x 19 in.

A case in point is the work of Modigliani. Although, as we have discussed before, the “primitivist” tendency of his faces, lacking the intimacy of the human gaze — often literally lacking eyes — and resembling masks, is a bit disconcerting. The figure in his hands becomes a kind of clay or wooden puppet, serving as an excuse for aestheticist manipulation. Nevertheless, there are moments in his work that strike me as sensitive, tender and full of sweet melancholy. It almost seems as if he wanted to capture a sense of intimacy, of personal encounter and participation, in his portraiture, but this was not allowed to him within his immediate modernist paradigm, an avant-garde world which could have taken it as merely passé, a thing academic in orientation. In a way, he hid behind the masks, but even the masks could not obscure his sensitivity of spirit.

In conclusion, let me underline that, when speaking of style, what I have in mind is more than what is commonly referred to as the “Byzantine style”, a term which primarily designates the given parameters of the pictorial principles of the tradition—its system or infrastructure of representation. This infrastructure is indeed to be respected as what has been acknowledged by now as arguably the most ecclesial in function within the liturgical context. But, a genuine and living style, having enargeia, implies much more, demonstrating not only engagement with the infrastructure, without being enslaved by it, but more importantly, a personal encounter between the painter and the subject depicted. Otherwise we would be advancing a form of sterile stylistic dogmatism. Therefore, style is best thought of as the manifestation of participation, as you have also suggested. It also presupposes, in my view, a kind of embodied meaning, the synthesis of thought and feeling in form, as mentioned in the beginning, in which visual and semiotic components are synergized. This understanding allows for the acknowledgement and possibility of multiplicity of styles within the tradition, since it is predicated, not on prescriptive formulas, but rather on the uniqueness of each icon painter’s living personal encounter with the subject depicted and the horizon of history.

Without genuine participation I’m afraid we will only continue to perpetuate empty mannerisms. The masters will look over our shoulders and rebuke the artificiality of our style.

Notes:

[i] By enargeia we mean the living quality, vitality and vividness of the image.

[ii] Ontophanic: manifesting being or the manifestation of the unique characteristics of a being.

[iii] For a critique of Mannerism see Jonathan Pageau, “The End of Desacralization in Art.”