Similar Posts

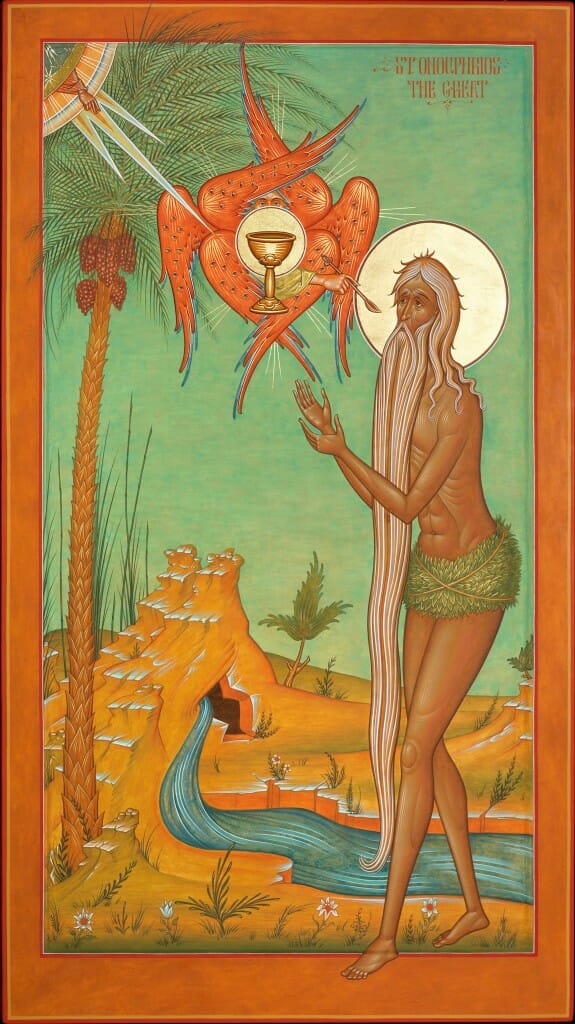

Contemporary icon by Fr. Silouan Justiniano,

St. Onouphrios the Great,

Egg tempera on wood, 18 1/4 x 32 1/4.

This icon applies the principles discussed in the article. It depicts the saint being given the Holy Eucharist by an angel, as described in his life. The composition is new. Although it is not a copy of a previous prototype it does not depart from Tradition. It is grounded in a very specific detail of the saint’s life and the general features that tie all of his icons together.

…Each one of us has his own peculiar way of expression…The capable artist is by no means a mechanical copier, but a creator in the true sense of the term. Unfortunately, even among iconographers there are some who have the idea that…Iconography is an art of copying. Such artists, by saying this, reveal quite clearly that they have understood nothing with regard to this art, and that they are incapable of probing its mystical depth, but occupy themselves only with the surface.

Photios Kontoglou,The Orthodox Tradition of Iconography

The real artist, who was once employed to serve man’s eternal destiny has nothing whatever to do in our civilization, other than to reflect our pathological preoccupation with time and lack of eternal purpose…The great civilizations, however tell us that our real happiness comes in fulfilling our cosmic purpose. The function of art is similar, on this level. And this is partly our dilemma.

Cecil Collins, Why Does Art Today Lack Inspiration?

No, I did not buy the aforementioned art magazine; I put it back on the rack. Others, however, have gone as far as to put all of contemporary art in the trash, as spoiled food, a dangerous contaminant to the spiritual life. There are also those who have shelved the traditional doctrine of art as irrelevant to our predicament today, a thing of the past. Perhaps, however, things are not that simple. Maybe something beneficial can come out of this clash of paradigms, unforeseen and unexpected. Discernment is the key.

Let us propose that not all that is labelled as “modern” or “contemporary” is spiritually vacuous. Nor is all the liturgical art seen today living up to its full potential. On the one hand, the non-liturgical artist may find clues in the traditional doctrine that may help to spiritually revitalize his art; on the other hand, the iconographer may benefit from contemporary art’s challenge to his conception of Tradition and creative freedom. The iconographer observes the art world from within the temple, while the secular artist peers in from the outside; the two encounter each other in the atrium, the threshold of the Sacred.[i] In this middle realm, where in fact the Sacred and profane overlap, both the non-liturgical and liturgical artist face a challenge. We hope that the confrontation may lead to self-knowledge, and to a dispelling of misconceptions. But before we consider how the threshold bears on art, let us take a look at the challenge of the iconographer.

Fear of License

It goes without saying that contemporary art suffers from the cult of novelty and extreme subjectivism. We shouldn’t use this, however, as an excuse to overlook that often today the iconographer suffers from a limited understanding of Tradition. It is taken to mean the restriction of creativity rather than freedom in the Spirit. And so, the gallery artist might be onto something; his suspicion might be justified when he sees that, often, contemporary icons appear stale, lacking in vitality and evidence of inspiration. Ironically, the 20th century revival of the icon has tended to instill in us the notion that Tradition is the ossification of artistic forms, rather than reawaken an awareness of its ever-renewing power. Safeguarding the “canon”[ii] has encouraged a morbid fear of innovation, making it difficult to access the Tradition today in a fresh way. This has given rise to a satisfaction in the regurgitating of old formulas and the mere imitation of prototypes which we have not made our own.

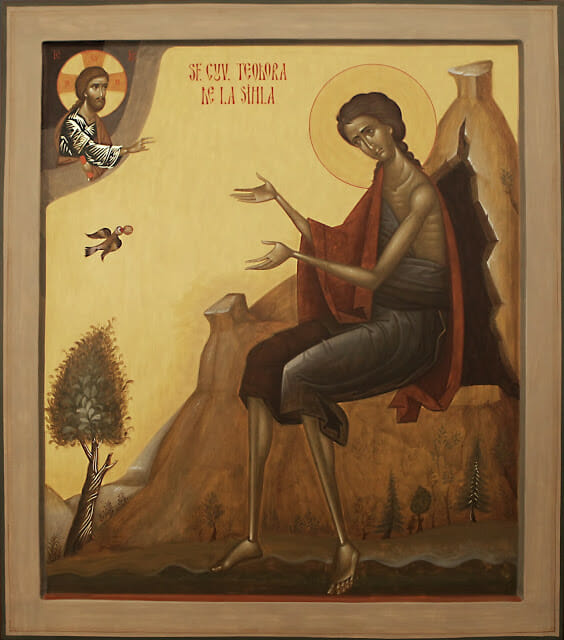

Contemporary Romanian icon by Razvan Gasca, St. Theodora de la Sihla, Egg tempera. The rest of the icons featured in the article show how icon painting is being revitalized in Romania with fresh pictorial interpretations. The painters avoid slavish copying and have genuine freedom of execution. These are good examples of the ever-renewing power of Tradition and how it does not quench the unique temperament of the painter.

Part of the problem can be seen in the constant reiteration: “icons are not art.” This rhetorical trope can be seen as a misinterpretation of the pioneers of the icon revival, who disdained Western art in an attempt to deliver the icon from its dominance. Be that as it may, the icon is indeed not to be judged according to the standards of “fine art.” Nevertheless, the trope can, or already has, become an overstatement that damages the revival of iconography. It presupposes that anyone can paint an icon, anyone can join the workshop – there is no need to have artistic skill. But, iconography is obviously an art, in the traditional sense of techne, the skillful joining together of parts, according to a right course of reasoning, requiring intellectual rigor, the mastery of principles and creativity.

We are told, “Only prayer and a pious disposition is needed.” But if artistic skill is not enough, neither is a pietistic attitude a guarantee for an authentic icon. A person that excels in doing good deeds does not necessarily know how to make good things. Consequently, what is being unwittingly promulgate is mediocrity and mechanical copying, wherein the iconographer is expected to suppress his intellectual involvement and creativity. The human component is undermined. With this attitude it matters little whether the icon is hand-painted or reproduced.[iii] Ironically, the icon, a witness to the unique personality of the saints (those who have realized their calling to deification in a particularized and unrepeatable manner) becomes an academic exercise that stifles the unique personality of the iconographer. The copying of prototypes is crucial as an initial step in training, but it is not to be seen as the all-defining component of iconography. Means should not be confused with ends.

Life in Christ presupposes the flourishing of our true and unique personality, conformity to our true nature or logos, in contradistinction to our ego-centric or individualistic identity. Therefore, the traditional practice of not signing the icon should not be interpreted as an aspiration towards the complete obliteration of the iconographer’s creative temperament. It is rather a reminder that only in humble cooperation with the Divine Craftsman will his art and personality flourish to its full capacity. Thereby he will be able to uncover nuances contained in the prototypes previously unnoticed and contribute unrepeatable expressions of Tradition. In undermining this side of the icon, seeking to protect it from “artistic license” and foreign cultural influences, we may in fact blunt its power, making of it a purely mechanical act that contradicts basic principles of Orthodoxy.

Contemporary Romanian icon by

Thoma Chituc,

Holy Fathers Simeon Stylites and Daniel,

Mixed technique (color water based emulsion), 70 x 80 cm

My initial excitement when examining the magazine on the rack came precisely from the vitality and expressive power of the artwork. This, in spite of the unedifying content. The magazine urged me to paint a potent icon, to come up with a new prototype according to Tradition. The irony is that the urge was induced, not by liturgical, but rather by non-liturgical art. This is something most iconographers would not like to admit. It would be safer to utter dismissive remarks about secular art. But, as the saying goes, the lady doth protest too much… The iconographer might not be aware that, at times, he covets the “freedom” he doesn’t possess. He betrays this while waving the banner of “tradition,” easily condemning the non- icon. Yes, the secular artist seeks freedom from suffocating restraint. In the end, the iconographer is no different in this regard. But his “freedom” does not equate with license. How, then, is he to understand his creative act?

Is it possible for the contemporary iconographer to produce enlivening and refreshing icons, able to quench the spiritual thirst in our vast desert of desacralized images? Will our icons compete with the colors, flashing lights, and mesmerizing virtual realities our civilization offers as an escape from the drudgery of secular life? Undoubtedly, but only when we will have made the Tradition our lifeblood and experienced it from within, as ever-renewing power, as accessible today as it ever has been. Only when we will have begun to discern, when we will have made the timeless pictorial principles of the icon our own –when we will have encountered the prototypes, not as podlinnik tracings observed as external to us, but as the heavenly realities or saints we are communing with, in the chamber of our heart, apprehending with our noetic eyes.

The logos, the “logical” structure[iv], of the subject must be known from the inside out, in such a way that it touches us, imprints us with its unique presence, and begins to guide the creative act. In such a process, although we will not seek self-expression for its own sake, our personal temperament will not be quenched, but rather given creative freedom in the Spirit, for “where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.”[v] And, “This is inevitable, only because nothing can be known or done except in accordance with the mode of the knower. So the man himself, as he is in himself, appears in the style and handling, and can be recognized accordingly.”[vi] Only when we paint from our experience and knowledge, arising from living communion with the subject depicted (rather than from the experience of others, whether they be from the 15th,14th, or earlier centuries), will our icons be full of vitality and authenticity, living expressions of immutable Tradition.[vii]

Contemporary Romanian icon by

Thomas Chituc,

Icon of the Nativity of the Holy Martyr Prince Constantine Brancoveanu

Mixed technique (color water based emulsion), 70 x 80 cm.

What has just been said about the creative act is in fact nothing new, but in full accord with the method followed by medieval craftsmen[viii], as described by Titus Burkhardt in “The Decadence and Renewal of Christian Art,” the final chapter of Sacred Art in East and West: Principles and Methods. He reminds us that the craftsman, in copying consecrated models or prototypes, never went about it “mechanically,” but rather always interpreted them through a process of “identification.” Burckhardt then goes on to suggest that this method is unavoidable if we are to renew Christian sacred art:

More particularly in the Middle Ages, every painter or sculptor was in the first place a craftsman who copied consecrated models; it is precisely because he identified himself with those models, and to the extent that his identification was related to their essence, that his own art was “living”. The copy was evidently not a mechanical one; it passed through the filter of memory and was adapted to material circumstances; in the same way, if today one were to copy ancient Christian models, the very choice of those models, their transposition into a particular technique and the stripping from them of accessories would in itself be an art. One would have to condense whatever might appear to be essential elements in several analogous models, and to eliminate any features attributed to the incompetence of a craftsman or to his adoption of a superficial and injurious routine. The authenticity of this new art, its intrinsic vitality, would owe nothing to the subjective “originality” of its formulation, and everything to the objectivity or intelligence with which the essence of the model has been grasped. The success of any such enterprise is dependent above all on intuitive wisdom; as for originality, charm, freshness, they will come of their own accord.[ix]

Keeping this in mind, let us also remember that no two homilies are identical in expression, although they proclaim the same Truth. It is the same with the rich variety of expressions seen in icon painting. The iconographer preaches the Gospel in colors and chants hymns of praise, trembling as he says, in the words of the Christmas sticheron, “How hard it is to compose hymns of love, framed in harmony.” With his art he paints the Word, plastically manifesting, indeed enfleshing, the Logos. This is truly an “artistic license” of kerygmatic[x] expression in free will. Does not Christ ordain it so, when he says: “Go into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature.”[xi]

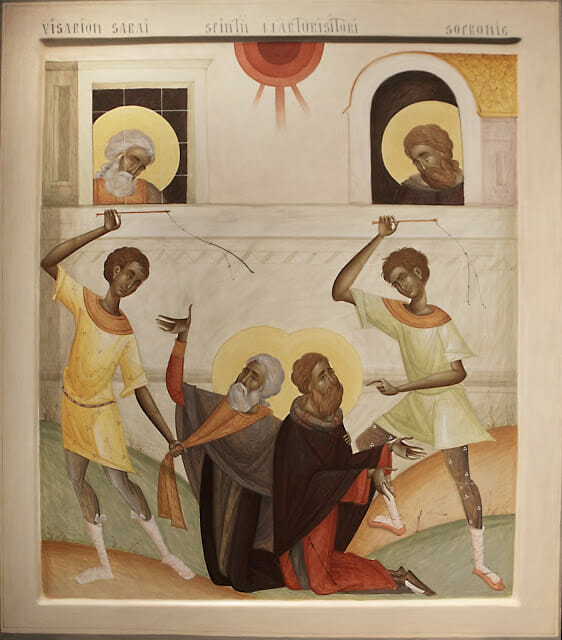

Contemporary Romanian icon by

Mihai Coman,

St. Vissarion (Bessarion) Sarai, and St.Sophronie of Ciorara,

Egg tempera.

The creative act is “free” insofar as it is directed by the nous which is imbued with Tradition. Techne, skill, or art, remains in the craftsman, as it is a science[xii], a knowledge, residing in him.[xiii] With his art he shapes, and molds matter; this is the “servile” act. The free and servile functions coincide, “the former consisting in the conception of some idea in an imitable form, the latter in the imitation (mimesis) of the invisible model (paradeigma) in some material, which is thus in-formed.”[xiv] The object itself is not the art; it is rather the artefact.[xv] The one pertains to the nous, and the other to manufacture.[xvi] The intermediary between the two is the imaginative faculty[xvii], which should not be equated with mere “fantasy.”[xviii] Rather, this faculty, guided by the nous, takes in sense impressions and combines them with images from the memory, arriving at pictorial solutions through a process of mental synthesis.[xix]

As Elder Sophrony explains, “We see a third aspect of the power of the imagination when a man uses his faculties of memory and imagination to think out the solution to some technical problem; and when he has done so his mind will seek means for the practical realization of his idea. This activity of the reason in association with the imagination plays a vital part in human culture and is essential for the economy of life.”[xx] From this, we can summarize what we mean by freedom in the creative act. In Ananda K. Coomaraswamy’s words, “The artist’s theoretical or imaginative act is said to be ‘free’ because it is not assumed or admitted that he is blindly copying any model extrinsic to himself, but expressing himself, even in adhering to a prescription or responding to requirements that may remain essentially the same for millennia.”[xxi] If these distinctions are kept in mind, there is no need to fear so-called “artistic license” in the doxology and homiletics of icon painting. We have been given a Spirit of freedom, not of bondage.

The Dilemma

This brings us to the challenge faced by the Orthodox artist engaged in non-liturgical art. What we have attempted in these series of posts is to highlight how the current notion of “fine art,” in our humanist, scientistic and secular culture, is an abnormality in the history of civilization. Nevertheless, most take it for granted as how art has always been, even though it’s just a recent European invention. This blind spot can be seen in an article written by an Orthodox architect, lamenting the loss of beauty and “absolute standards” in the arts brought about by the onslaught of modernism.[xxii] However for him, as far as painting is concerned, traditional art means nothing more than either the academic atelier, realist or classical styles.[xxiii] Likewise, for some, the more recognizable, pretty and unthreatening (without requiring too much thought), the more Victorian in flavor, the better. Yet, even the innocuous idyllic landscape, magically precise still life, and alluring nude are not lacking in metaphysical implications.[xxiv] For some it suffices to embrace this notion of “traditional art” as an answer to the pressing questions that the Orthodox contemporary artist faces. But as we have already said, this amounts to the making of Tradition nothing more than ideological and reactionary conservatism. And there has to be more to overcoming the challenge than merely “pandering to prudishness or excessive sensibility.”[xxv]

The Orthodox engaged in contemporary art then lives in-between the two worlds of Tradition and secular humanism: between a theocentric (sacred) culture and an anthropocentric (desacralized) culture. He is constantly faced with the dilemma of how to reconcile them. Sooner or later he will find himself asking whether there is a conflict between the principles of his faith and the practice of his art. Needless to say, the answer will not be simple. Here we’re not proposing an outright abandonment of non-liturgical art. Not everyone has been given the vocation of icon painting; neither is the current paradigm of art going to just disappear. There will be Orthodox who continue to participate in the contemporary art world. Knowledge of the traditional doctrine of art may perhaps illumine some of the blind spots such an artist will inevitably encounter. The more he is convinced by the veracity of the traditional philosophy, the more he will realize, as Brian Keeble says, that “Unlike his traditional forebears who could rely upon a measure of consensus as to the nature of reality and of man, as well as to the function of the artist in his relationship to the wider social context, the modern artist is in this respect without lineage and true patronage.”[xxvi] In other words, in playing the game of contemporary art, he will inevitably have to go against the grain of relativism, one of its fundamental guiding principles. The more he embraces the traditional philosophy, the more he will perceive the tension.

If the contemporary artist is unwilling to reassess the credence of the “art for art’s sake”[xxvii] paradigm, placing himself above good and evil and denying responsibility for his aesthetic choices, no more can be said. Since, for him, art has never been a gift from above, then the idea of returning it to God in a sacrifice of thanksgiving is irrelevant. In his hands, as Plato would put it, art is sophistry, a tool for his solipsistic concerns and a detriment to society.[xxviii] Neither aestheticism (aesthesis), which amounts to nothing more than sensationalism, nor self-expression, which amounts to exhibitionism, nor the “shock value”[xxix] of transgressing social taboos in the name of “high culture,” will suffice.[xxx] This is not to say that the masterful execution of the work on its own terms should be completely dismissed. Credit is to be given where credit is due. However, “A bomb may be perfectly well made by the art of the bomb-maker, but is the lethal explosion which demonstrates his perfected skill a good that promotes the perfection of life? Such a question help us to understand why, according to the traditional philosophy, the virtue of art, while not being confused with moral virtue, is nevertheless closely related to it. No one acts in isolation.”[xxxi] Hence, the artist cannot afford to avoid asking himself whether or not his work will be for the good or ill of the community at large.[xxxii]

In short, virtuosity is only half of the matter, and our likes and dislikes only cloud discernment. The aim, the import, must be assessed in spite of our tastes. If what is being made is not meant to feed the inner man and lead us to the overcoming of our limitations (by reminding us of our Origin, our Archetype, to whom we are meant to return), then we shouldn’t call such art “original.”[xxxiii] What does the work take for granted? What does it deliver? Of what is it significant?

Notes:

[i] See Aidan Hart, Beauty, Spirit, Matter: Icons in the Modern World, Gracewing, Herefordshire, UK, 2014, p. 191; Also, by the same author, Christianity and Sacred Art Today: The icon and an assessment of western art, A lecture given 6 October, 2005, at Hillsdale College, Minnesota, US. http://aidanharticons.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/CHRISTIANITY-AND-SACRED-ART-TODAY.pdf; The Icon and Art, A talk given to the School of Economic Science, Waterperry, Oxford, 7 March, 2000. http://aidanharticons.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/The-Icon-and-Art.pdf

[ii] Emilie Van Taack, the French iconographer, teacher, and student of Leonid Uspensky explains: “Generally, it is said that an icon must follow very strict canonical rules, but this is not true. There is only one rule, Rule 82, decreed by the Council in Trullo, part of the Sixth Ecumenical Council. This is the iconographic canon, in which it is stated that the icon painters must follow older painters, that they must be in the stream of tradition, but exactly how they are to do it is not described. What is stated is that an icon must show both the humility of the Man Jesus and His glory as God; that is, it must manifest the Incarnation…We have to learn from the old, but we do not have to copy the old exactly…In defining what is “canonical” in icon painting, we have, of course, many beautiful old canonical icons to refer to. But canonicity is difficult to define. I cannot tell you what is canonical, because the icons themselves define the canons. It is a circle, and we must accept it like this. By looking at these beautiful icons, studying them, copying them, little by little they help you to see in yourself this image of Christ, and then you will be able to paint it without looking to the old, because you will have it in your heart.” Emilie Van Taack interview, “Perspective and Grace: Painting the Likeness of Christ,” Road to Emmaus, Vol. VII, No.2 (#25), pp. 40-41. http://www.roadtoemmaus.net/back_issue_articles/RTE_25/PERSPECTIVE_AND_GRACE.pdf

[iii] “Does it matter whether we manufacture things by machine or by hand? After all, these are simply different techniques for the production of necessary goods, and machine production is by far the most efficient. Yes, it does matter. The purely utilitarian standard of efficiency involved in machine production blurs the distinction between skill and technique. It makes no acknowledgement of the intellectual responsibility that is proper to man as a skilled maker of things. It has become necessary to have a clear understanding of what has been usurped in the domain of skill, since never before has the artist (as homo faber) had to work in a social milieu so completely dominated by the machine- that device of absolute utility whose form and function so ruthlessly excludes all human qualities in the way it equates means to ends.” Brian Keeble ed., Every Man an Artist: Readings in the Traditional Philosophy of Art, World Wisdom, Bloomington, Indiana, 2005, p. xvii.

[iv] “Icons impinge on our consciousness by means of the outer senses, presenting to us the same supra-sensible reality in “aesthetic” expressions (in the proper sense of the word, that which can be perceived by the senses). But the intelligible element does not remain foreign to iconography: in looking at the icon one discovers in it a “logical” structure, a dogmatic content which has determined its composition.” Vladimir Lossky, “Tradition and Traditions,” The Meaning of Icons, SVS Press, Crestwood, NY, 1989, p. 22.

[v] I Cor. 3:17; Coomaraswamy notes: “Ideas are gifts of the Spirit…No matter how many times they may already have been ‘applied’ by others, whoever conforms himself to an idea and so makes it his own, will be working originally, but not so if he is expressing only his own ideas and opinions.” A. K. Coomaraswamy, “The Nature of Medieval Art,” Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India, 1972, p. 38.

[vi] Ananda. K. Commaraswamy, “Art, Man and Manufacture,” Our Emergent Civilization, Ruth Nanda Ashen Ed., Harper and Brothers, NY, 1947, p. 162.

[vii] “Yes, we now have many icons, which are simply reproductions of old icons. Uspensky insisted very strongly that we are not to copy, but this fact can also be misunderstood, we have absolutely no reason to reproduce an old icon, because this means that we have no life in ourselves. What we want to do is not to reproduce an icon outside ourselves; we have to take it inside and regive it. Even if we copy, we have to have this process. If we are living in a spiritual way, it will not be just a copy, it will be a living copy.” Emilie Van Taack, op. cit., pp. 57-58.

[viii] The medieval craftsman is to be understood as an example of one who embodies and works according to the principles of the traditional doctrine of art.

[ix] Titus Burckhardt, “The Decadence and Renewal of Christian Art,” Sacred Art in East and West: Principles and Methods, Perennial Books Ltd., Middlesex, UK, 1986, p.160.

[x] From kerygma (from the Greek kerugma), the word in the New Testament meaning the “preaching” of the Gospel and the content of such preaching. It also implies the crying out, announcement, or proclamation of a herald.

[xi] Mark 16: 15

[xii] “But medieval art was not like ours “free” to ignore truth. For medieval man, Ars sin scientia nihil; by “science we mean, of course, the reference of all particulars to unifying principles, not the “laws” of statistical prediction.” Coomaraswamy, op. cit., 1947, p. 156.

[xiii] “…Art is identical with a state of capacity to make, involving a true course of reasoning. All art is concerned with coming into being, i.e. with contriving and considering how something may come into being which is capable of either being or not being, and whose origin is in the maker and not in the thing made…” Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 6, 4.

[xiv] The context is the followings: “In the production of anything made by art, or the exercise of any art, two faculties, respectively imaginative and operative, free and servile, are simultaneously involved; the former consisting in the conception of some idea in an imitable form, the latter in the imitation (mimesis) of this invisible model (paradigma) in some material, which is thus in-formed. Imitation, the distinctive character of all the arts, is accordingly two-fold, on the one hand the work of intellect (nous) and on the other of the hands (cheir).”A. K. Coomaraswamy, “Athena & Hephaistos,” On the Traditional Doctrine of Art, Golgonooza Press, Ipswich, UK, 1977, p. 19.

[xv] “Art, from the Mediaeval point of view, was a kind of knowledge in accordance with which the artist imagined the form or design of the work to be done, and by which he reproduced this form in the required or available material. The product was not called ‘art,’ but an ‘artefact,’ a thing ‘made by art’; the art remains in the artist. Nor was there any distinction of ‘fine’ from ‘applied’ or ‘pure’ from ‘decorative’ art. All art was for ‘good use’ and ‘adapted to conditions.’ Art could be applied either to noble or common uses, but was no more or less art in the one case than in the other.” Coomaraswamy, “The Nature of Medieval Art,” op. cit., 1972, p. 111.

[xvi] “The artist is given the commission and is expected to practice his art. It is by this art that he knows both what the thing should be like and how to impress this form upon the available material, so that it may be informed with what is actually alive in himself. His operation will be twofold, ‘free’ and ‘servile,’ theoretical and operative, inventive and imitative. It is in terms of the freely invented formal cause that we can best explain how the pattern of the thing to be made or arranged, this essay or this house, for example, is known. It is this cause by which the actual shape of the thing can best be understood; because ‘similitude is with respect to form’ of the thing to be made, and not with respect to the shape or appearance of some other and already existing thing; so that in saying “imitative” we are by no means saying ‘naturalistic’.” Coomaraswamy, op. cit., 1947, p.158-9.

[xvii] “In creatures endowed with intelligence this imaginative faculty of the soul is an intermediary between the intellect and the senses.”

See St. Gregory Palamas, “Topics of Natural and Theological Science and the Moral and Ascetic Life: One Hundred and Fifty Texts,” Chap. 17 in G. E. H. Palmer, P. Sherrard, K. Ware, eds., The Philokalia Vol. IV, Faber and Faber Inc., p. 353.

[xviii] We should note here that according to St. Gregory Palamas the imaginative faculty plays a crucial role in acquiring knowledge, “with regard to the laws of nature, and every method and art [our emphasis]. And in brief with regard to all knowledge acquired from the perception of particulars.” He adds, “Such knowledge we gather from the senses and the imagination by means of the intellect [nous]. Yet no such knowledge can ever be called spiritual, for it is natural, things of the Spirit being beyond its scope (cf. 1 Cor. 2: 14).” So in no way are we elevating the imagination to a quasi-divine faculty in the Romantic sense. However, as with the other faculties of the soul, it can either be stamped or stirred directly by the Spirit, the spiritual knowledge of the nous, by the passions, or demons. Palamas, Chap. 2o, Ibid., p. 354; As to the appropriate use of imagination in the unseen warfare, St. Nicodemos reminds us: “Finally, it is permissible, when fighting against certain inappropriate and evil imaginations presented by the enemy, to use other appropriate and virtuous imaginations.” St. Nicodemos of the Holy Mountain, A Handbook of Spiritual Counsel, Paulist Press, Mahwah, NJ, 1989, p.152.

[xix] We can also call this process the “inventive” operation of the imaginative faculty. See above, note xvi; In its inventive capacity the imagination serves as an instrument: “An object of art differs from an object of nature because it is the product of a human mind. The imagination is itself an instrument and, like others, it marks its product with qualities that are its own. Images produced in an artist’s imagination have a quality which results from their origin. The objects which are the material copies of these images have that stamp also. The word used to describe this in works of art is the word formal. Formal qualities are in general concerned with color and sound relationships, space and line relationships, and rhythms and harmonies…” John Howard Benson & Arthur Graham Carey, “The General Problem,” Keeble ed., op. cit., pp. 108-09; The inventive operation defined here is not to be confused with the invention Kontoglou refers to when writing: “Invention, as it was called by the old masters, is not at all needed in a work of the Tradition, because “invention” constitutes ostentation and self-display – that is, an insertion of then ephemeral into the eternal.” Photios Kontoglou, “The Orthodox Tradition of Iconography,” in Constantine Cavarnos ed., Fine Arts and Tradition, pp. 58-59; Likewise, echoing Plato, Coomaraswamy says: “It is the irrational impulses that yearn for innovation. Our sentimental or aesthetic culture- sentimental, aesthetic and materialistic are virtually synonyms- prefers instinctive expression to the formal beauty of rational art… We cannot give the name of art to anything irrational.” A. K. Coomaraswamy, op. cit., 1972, pp. 11-12, 22.

[xx] Archemandrite Sofrony, The Undistorted Image, The Faith Press LTD, London, 1958, p. 86.

[xxi] Our italicized emphasis. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, “The Christian and Oriental, or True, Philosophy of Art,” The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, World Wisdom, Bloomington, IN, 2004, p.132.

[xxii] He rightly observes, “The Arts have been for over a century philosophically and ideologically bankrupt. They are an index of the flow of thoughts of the ages…Man does not invent the absolutes, standards, or order, but discovers them. The wellbeing of civilization depended upon discovering that order and adhering to it. This view was the basis of the creation of all works of art, including architecture, literature, music, and crafts. Similarly, non-Christian cultures of the world both ancient and modern, literate and non-literate, took their cues for form and beauty from the natural or created world. For at least 35 centuries or more, this had resulted in a progressive realization of how to create an order and harmony of form in daily life. With this realization came an astonishing variety of forms and expressions. From the pyramids to the Parthenon… as well as all other works of art, there existed a recognized underlying order.” Deacon James Bryant, Reclaiming the Arts: An Orthodox Perspective, Православие.Ru, 4 мая 2012 г. http://www.pravoslavie.ru/english/53335.htm.

[xxiii] “There is emerging, however, a dissatisfaction on the part of many with the current state of affairs, and a desire to rediscover the rich heritage of our past. In the last 20 years there have been springing up private ateliers which offer a classical education in the Arts, but they are referred to by the mainstream schools as mere teachers of “crafts”. One in Minneapolis, Atelier Lack, represents an unbroken line to the classical era handed down from master to apprentice.” Ibid.; In making a distinction between the “classical” or academic painting that Deacon James calls “traditional” and art made according to the traditional doctrine of art, we are not saying that all such painting lacks in beauty, spiritual resonance and relevance, especially when compared to most contemporary art. Likewise, when using terms such as sacred and profane art, we should be cautious and take care to notice the varying degrees of inwardness, superficiality, worldliness, or sacriligiousness, in what is generally classified as “profane.” Some works are truly profane while it is better to call others non-liturgical or secular. Whether it be sacred or profane art, the differences should be acknowledged when works are compared among themselves.

[xxiv] “To what can we attribute the obsession with still life that began in the Renaissance?…Just as the Renaissance involved a general turning away from spirit and towards nature, so art itself became less spiritualized and more naturalized. The still-life obsession can plausibly be thought of as the central artistic manifestation of the so-called scientific revolution: an almost pathological desire to understand nature and flesh from all angles, from every perspective, as if by painting it over and over one could somehow plumb its depths, get it to surrender its mystery…The problem is that the radiance of form that the artist must seek to portray is a brightness not just of flesh but of spirit. To seek perfection of form in the mere dissection of nature is as futile as seeking the cure of disease in the mere cutting up of a body, and leads only to sterile realism that promises insight but delivers none.” David S. Oderberg, Perennial Philosophy’s Theory of Art, Quadrant Magazine, January- February 20, Vol. 48 Issue 1/2, 2004, pp.71-72.

[xxv] Ibid., p. 74.

[xxvi] Brian Keeble ed., Cecil Collins: The Vision of the Fool, Golgonooza Press, Ipswich, UK, 1994, p.12.

[xxvii] “… ‘Art for art sake’…to the extent that it implies an exalted status for art out of proportion to its place in society, it implies a kind of idolatry, an idolatry all too evident today in the world of collections and collectors, galleries and mega-exhibitions, and an endless chatter about the place of art which ipso facto gives it a place it does not deserve.” Oderberg, op. cit., p. 73.

[xxviii] Plato, Gorgias 465A; Laws 890D; Republic 608A

[xxix] What we mean here by “shock value” is to be differentiated from the beneficial cathartic function some works of art can have within limits. “Shock value” is an indulgence having no redemptive purpose, whereas katharsis brings about transformation, focus from things mortal to things immortal. The idea of katharsis is to be found in Plato and Aristotle, and pertains to “purification…from passions (pathêmata); we must bear in mind that, for Aristotle, tragedy is…certainly not a periodical “outlet” of- that is to say, indulgence in- our “pent-up” emotions that can bring about an emancipation from them; such an outlet, like a drunkard’s bout, can only be a temporary satiation. In what Plato calls with more approval the “more austere” kind of poetry, we are presumed to be enjoying a feast of reason rather than a “break-fast” of sensations…His katharsis is an ecstasy or liberation of the “immortal soul” from the affections of the “mortal”…We must remember that all artistic operations were originally rites, and that the purpose of the rite (as the word teletê implies) is to sacrifice the old and to bring into being a new and more perfect man.” Coomaraswamy, A figure of Speech or a Figure of Thought?, op. cit., 2004, pp.25-26; Also see Coomaraswamy, Samvega: “Aesthetic Shock,” op. cit., 2004, p. 193-99; The film maker Andrey Tarkovsky also valued the notion of catharsis. For him the viewer is not merely to be taught to be good, but rather shocked, shaken, and thereby made receptive to good. Andrey Tarkovsky, “Art- a yearning for the ideal,” Sculpting in Time, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1998, p. 50.

[xxx] Even the secular art historian acknowledges the low transgressive levels art can reach nowadays. After describing the most extreme examples Julian Stallabrass says, “Contemporary art seems to exist in a zone of freedom, set apart from the mundane and functional character of everyday life, and from its rules and conventions. In that zone, alongside quieter contemplation and intellectual play, there flourishes a strange mix of carnival novelty, barbaric transgressions of morals, and offences against systems of belief.” Julian Stallabrass, Contemporary Art: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2004, p. 1.

[xxxi] Keeble, 2005, op. cit., p. xvi.

[xxxii] On the question of ethics in art David S. Oderberg says, “Art therefore, contains within itself a sacred moral duty to which all the wonders of skill, technique and innovation are subordinate. That duty is violated if the artist sets out to disgust or degrade, or to titillate. If he wants to show his cleverness, let it be the holy cleverness of utter self-effacement. If he wants to shock, let it be righteous shock, not the shock of the sewer whose stench makes proper breathing all but impossible. The artist must always be a member of a community of men first and artist second. As such, he must be conscious of the effect of his work on others, and whilst not pandering to prudishness or excessive sensibility, he must know that the very power at his command can be used for the good as well as ill. Let his creative impulse soar, but let it not leave the world on men behind.” Oderberg, op. cit., p.74.

[xxxiii] See Philip Sherrard, “Art and Originality,” The Sacred in Life and Art, Denise Harvey (Publisher), Evia, Greece, 2004, pp. 54-67; Also see above, note v.

Dear Fr. Justiniano,

I enjoyed reading your thought-provoking article, and will ponder more on it…

Please, I would like to know what is meant by “color water based emulsion”, with reference to the icons of Thomas Chituc. Thank you for any help you may be able to offer in this regard.

Sincerely,

John

Hello John,

I have asked Thoma Chituc and he tells me that the “mixed technique” involves using different kinds of water based colors on the same panel, such as tempera and acrylic for some backgrounds.

He doesn’t combine but rather layers the media. For example, if he needs a vibrant cream colored background, he may use acrylic in order to make sure that it fixes well on the panel. That way he can do other things on top without removing it. Basically, when using many transparencies, if only egg tempera is used, they tend to be fragile and can be ruined quickly. So he avoids the problem by using thin acrylic layers as well to guarantee good adhesion. Any differences of paint surface effects of each media (sheen, texture, mat, gloss, etc.) is then harmonized by the final varnish. I hope this helps to clarify.

Dear Fr. Justiniano,

Thank you for your reply, and for asking Thoma Chituc about his techniques. His reply about the mixed media is interesting, as it seems to me that egg tempera is not compatible with acrylic; that is, from personal experience as well as research, egg tempera paint will not dry when used over an acrylic gesso—- perhaps this is another matter if it is acrylic ‘paint’ in question, yet it seems that the plastic nature of acrylic does not provide the absorbency the egg tempera requires.

John

Hello John,

Good point. I actually had similar questions in my mind as to the compatibility of the two mediums. As you say generally speaking the plastic nature of acrylic would not be absorbent enough. This would definitely be the case if working on an surface prepared with many layers of acrylic gesso and if using acrylic paint of the paint tube varieties. However, Toma is using panels prepared with traditional gesso, which consists of a mixture of calcium carbonate (chalk) and rabbit skin glue (sometimes sturgeon fish glue); a very absorbent surface to work on as you might already know. I think he mixes dry pigments with acrylic emulsion to prepare his “acrylic paint.” So this would enable him to further retain absorbency, or reduce the amount of plastic-like consistency, when using thin layers. All of this I think gives him a lot of flexibility. By working in thin layers he would then retain absorbency, thereby rendering the additional egg tempera layers compatible.

Dear Fr. Justiniano,

Thank you for your detailed explanation, it makes sense; I have the products on hand, so perhaps I’ll experiment.

Sincerely,

John

I am happy to have found your website. It’s truly well-done! This website bears the information that several outstanding volumes would contain about the subject of Orthodox aesthetics. Each article is engrossing to read, appropriately lengthy, and thoughtfully and deeply written. Blessings for your terrific evangelism to lovers of the beautiful.

I believe both these articles address nearly all the issues brought up in Fr. S’s essay and profiles the challanges all artists face.

http://www.denisdutton.com/kitsch_macmillan.htm

http://www.sharecom.ca/greenberg/kitsch.html

Bravo, Fr. Silouan! Awesome article. Love it.

The last section “The Dilemma” and in particular the final paragraph seem incomplete to me. That last paragraph is quite loaded with what could really be a whole ‘nother article. And, I feel like you might be overlooking something that seems fairly clear to me. Namely, there is a good mode of art that is non-liturgical but not for shock value, self expression or sensationalism, but rather for compassion. This art’s aim is to present modern man with a vision of his own vulnerability and fallenness. It is closely related to cynical social commentary but ideally this is done in a loving way that is not without hope. I think of it like as if liturgical art is the first half of the Jesus Prayer describing “Lord Jesus Christ” as archetype and origin. And then this other art of compassion is the second half of the Jesus Prayer in which we describe ourself as “Sinner.”

As contemporary men living in the digital age we get so stuck in our heads (proud, analytical, disconnected from our bodies, allured by fantasy) that we forget we happen to have our heads stuck up our asses (by which I mean enslaved to passions, myself included!). Art of compassion holds up a loving mirror to remind us that we have forgotten our calling. It reveals our corrupt thoughts out in the open so that we may see them more clearly for what they are.

Another way to say it is that as sinful men we are always playing with the rattling tail of the snake, not knowing what we are doing but entranced by it’s various allures and promises of pleasure. Art of compassion can be like prophecy, revealing to us the body and head, fangs and venom of that snake connected to the rattle we’re playing with.

So, a follow-up question I have is do you think there is any place for this kind of activity in a liturgical setting? Some might call this activity Satire. I am not educated well enough to know how to describe this mode of art best or to know its proper context.

The closest thing I can think of is in old illuminated manuscripts like the Paris Psalter, you see Moses receiving the 10 commandments while at the bottom of the painting a Hebrew is sitting de-robed with his(/her?) bulbous rump hanging out – clearly to me indicating a state of debauchery.

The holy scriptures contain many stories of our righteous ancestors falling into sin. Iconography seems to shy away from immortalizing those events, but isn’t there sometimes a place for recognizing what happened and what was repented from? If all we ever do is show the archetype we can forget our lowliness?

You take it from here. You’re really good at this.

baker

I know it’s silly to post a reply to my own reply, but I’m going there.

Maybe art of “compassion” is not quite the right word, but rather art of “confession.” I like that better.

Confession can take the form of confessing my sins, which has a self-expressive nature but is conditioned by humility to not be indulgent but rather an occasion for restoration. A beautiful confession of sins can prick the heart of a listener and inspire them to draw closer both to the confessor and to God. Literature is probably the best-suited art form, but it is possible in others. Dostoevsky and Flannery O’Connor come to mind. Caricature illustration honestly does this quite well in the right hands, even though it might not always be considered fine art.

Confession can also take the form of confessing God’s praises through delight in the created order of the cosmos. This mode of art is maybe close kin to aesthetic indulgence or sensationalism, but I believe can be instead a doxology that lifts the mundane up, honors it, shows its potential to be shot through with light, dancing in the exuberant energetic cosmic symphony. Van Gogh nailed it in this respect, and others who delighted in forms or concepts got it in their own respective ways.

Please let me know if you disagree or have a better way of saying this.

with your prayers,

baker

You’re right Baker. Thanks for your constructive comments. I always look forward to hearing your take on these posts. The last section “The Dilemma” is only a cursory treatment of a multifaceted and complex problem. In fact, my original essay has two more sections. I thought I would end the series with this latest post (“The Dilemma”), but perhaps I will add the remaining sections. We’ll see. In the additional sections I make reference to the positive potential of non-liturgical art, its capacity to act as a threshold to the sacred. This is what I think you’re alluding to regarding compassion, Dostoevsky, Van Gogh, and the examples given by Aidan Hart when he speaks on threshold art.

Although I don’t touch on dimensions of compassion or satire, I nevertheless point to something related, the cathartic potential of art (see end note xxix, which states: “What we mean here by ‘shock value’ is to be differentiated from the beneficial cathartic function some works of art can have within limits. ‘Shock value’ is an indulgence having no redemptive purpose, whereas katharsis brings about transformation, focus from things mortal to things immortal. The idea of katharsis is to be found in Plato and Aristotle, and pertains to ‘purification…from passions (pathêmata); we must bear in mind that, for Aristotle, tragedy is…certainly not a periodical ‘outlet’ of- that is to say, indulgence in- our ‘pent-up’ emotions that can bring about an emancipation from them; such an outlet, like a drunkard’s bout, can only be a temporary satiation. In what Plato calls with more approval the ‘more austere’ kind of poetry, we are presumed to be enjoying a feast of reason rather than a ‘break-fast’ of sensations…His katharsis is an ecstasy or liberation of the ‘immortal soul’ from the affections of the ‘mortal’…We must remember that all artistic operations were originally rites, and that the purpose of the rite (as the word teletê implies) is to sacrifice the old and to bring into being a new and more perfect man.’ Coomaraswamy, A figure of Speech or a Figure of Thought?, op. cit., 2004, pp.25-26; Also see Coomaraswamy, Samvega: ‘Aesthetic Shock,’ op. cit., 2004, p. 193-99; The film maker Andrey Tarkovsky also valued the notion of Katharsis. For him the viewer is not merely to be taught to be good, but rather shocked, shaken, and thereby made receptive to good. Andrey Tarkovsky, ‘Art- a yearning for the ideal,’ Sculpting in Time, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1998, p. 50.”).

This I think touches on what you describe as an art that helps us “wake up” from being “entranced by…various allures” and reminds us of our true dignity and calling. So I do agree that there is an art of compassion. I think mainly of the work of Kathe Kollwitz as a good example. When it comes to Satire I think of William Hogarth and Honore Daumier.

As to whether there is a place for this dimension in the liturgical setting, I think there already is, but within limits. In the monastery we get to read the lives of the saints daily during Matins. There we can find some accounts that might seem graphic. For example, there is a saint (whose name now escapes me) that, after years of asceticism, commits fornication and then murders the woman. He later repents. Today we commemorate him.

What about the life of St. Mary of Egypt? Or the detailed descriptions of the various tortures the martyrs undergo? Do they not display the irrational behavior of man in his cruelty? These are depicted in all their vividness, within the limits of liturgical propriety, in the Decani Monastery frescoes and the illuminations of Basil II’s Menologion. As you mention, Scripture is not puritanical or squeamish about mentioning the reality of mans’s sinfulness and failures, and these are read in the services (think of the recent commemoration of the Innocents slain by Herod).

Another good example is the service for the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, which describes the drunkenness and lust of Herod as he sees Salome dancing and the bloodthirsty cruelty of Herodias asking for the prophets head. But I think that all of this is always kept in balance by the mental and temporal nature of reading. We imagine a vague image of the event and the fact that we “pass through” these descriptions, of man’s failure to realize his true calling as we read, helps us not get trapped in a sickly fascination for the negative, grim and gory. In a pictorial context (iconography) I believe things are a bit different, since we get an image all at once which we are meant to “dwell” on in prayer, so to speak. The nature of pictorial representation is that it renders the scene vividly in front of your eyes, hence the necessity to tone things down a bit, in order to keep us from our tendency towards the “impassioned gaze”. So whether in Scripture, the menologion, hymnography, or iconography, the focus of satire (man becoming a caricature of himself in his passionate behavior) and the shocking, or “graphic” depictions, remain in the periphery to the central point which is deified humanity–sanctity.

I agree that there is a place for “recognizing what happened and what was repented from”, but this always takes place by a recollection of our Archetype, which in turn reminds us of our true dignity and calling to become gods. In other words it is inevitable that as we contemplating the Archetype as in a mirror we are reminded of our lowliness and inspired to overcome those things that keep us in bondage and deception.

I chose to gloss over some things; small doses in slow increments is the best strategy where this subject matter is concerned. Talking “art” can be as volatile as talking religion and politics at the dinner table.

In Christ,

Fr. Silouan

So right on. Thank you for sharing these thoughts.

with your prayers,

baker