Similar Posts

On the Gift of Art…Part V:

The Threshold

By

Fr. Silouan Justiniano

There is, then a distinction to be drawn between a significant [meaningful] and liberating art, the art of those who in their performances are celebrating God…in both His natures immanent and transcendent, and the in-significant [meaning-less] art that is “colored by worldly passion” and “dependent on moods.” The former is the highway art that leads directly to the end of the road, the latter a “pagan art” and eccentric art that wanders off in all directions, imitating anything and everything.

A.K. Coomaraswamy[1]

Art reconciles us to life. Art is the introduction of order and harmony in the soul, not of trouble and disorder… If an artist does not accomplish the miracle of transforming the soul of the spectator into an attitude of love and forgiveness, then his art is only an ephemeral passion.

Nicholai Gogol[2]

What then is the option for the Eastern Orthodox Christian who has no vocation in the realm of liturgical art, such as iconography, yet is in fact a contemporary artist? This question was asked in the outset of our series of posts On the Gift of Art and it still needs answering. A possible answer lies in the idea of “threshold art,” which Aidan Hart has often mentioned in his articles. It is a concept most likely developed from indications given by Philip Sherrard who wrote in The Sacred in Life and Art, “A work of art which can bring us to the threshold of mystery is not the same as a sacred work of art, which discloses the mystery itself and makes us share in it.”[3] So let us look at some of the implications of the “threshold”.

Definitions

Sherrard’s statement might at first appear to be an outright dismissal, or perhaps just a back handed complement of gallery art, but there is more. Without a doubt he clearly places sacred or liturgical art in the higher category, above gallery art. Yet, in making this distinction he does not completely undermine the spiritual possibilities and significance of non-liturgical art, rather, he asserts it, albeit within limits. Sacred art, as its various forms harmoniously come together in the symphony of Church cult, sacramentally places us in the presence, within the mystery of the Sacred; whereas gallery art may function, in spite of its disadvantages, as a transitional border leading from the profane to the inner sanctum of the Sacred. It can in fact point the way towards and give us intimations of the numinous. Yes, non-liturgical art might have a “lower” status in its capacity to fulfill the highest function of art, the joining of culture with the Divine, yet, it is not wholly deprived of spiritual efficacy. So how are we to bring it successfully to this level?

It goes without saying, hoping to achieve something of the kind is quite a challenge to take on by the contemporary secular artist. Perhaps it would be asking for too much. Nevertheless, I believe that it’s an unavoidable responsibility for an artist that calls himself Christian. There has to be more to his activity than narcissistic self-gratification or the exhibitionism of personal feelings. There has to be the realization that, as Andrey Tarkovsky once put it, “Modern art has taken a wrong turn in abandoning the search for the meaning of existence in order to affirm the value of the individual for its own sake. What purports to be art begins to look like an eccentric occupation for suspect characters who maintain that any personalized action is of intrinsic value simply as a display of self-will.”[4] And, as he continues, calling to mind the idea of sobornost within the Church and the communal implications of liturgical art, “But in artistic creation the personality does not assert itself, it serves another, higher and communal idea.”[5] So, if part of our task as Orthodox Christians is the “higher communal idea” of baptizing and the transfiguring of culture, perhaps for the non-liturgical artist the pursuit of “threshold art”, and the shedding of the individualistic paradigm, is the way to start.

It can be said that the concept of threshold art maintains at least a portion of the traditional doctrine of art as discussed earlier, mainly in its emphasis on the capacity of art to symbolically connect, or join together, with the Sacred. That is, it touches on and reminds us of the sacramental potential of art.[6] Hence, we come back full circle to our first post, wherein we mentioned the religious roots of art. Ars (Latin for art), in fact, relates to religio (Latin for religion), both of which etymologically connote “to reconnect” or “join together fittingly.”[7] It’s an unavoidable fact, which even the militant secularists can’t deny, that in the history of mankind for millennia art has always been inseparable from religion. Our contemporary cultural predicament in this respect is rather anomalous, hardly a sign of “progress”. So the concept of threshold art asserts this fact and gives us a viable alternative to today’s predominant ideological thrust of desacralization in the realm of culture.

But, we should be careful not to overemphasize the sacramental implications of threshold art. The point is not to erase, blur or conflate, the distinctions between the realms of the sacred and profane. The hierarchy of importance, the “sacred order” must be maintained, between the higher and lower, inner and outer, Center and periphery, the temple in which we find the Holy of Holies and the unconsecrated world that lies outside. Sacred art moves out into the world from interiority,[8] it discloses the inner mystery of the initiated; whereas threshold art strives to move from the dispersion of the outer world back into the border, that is, the antechamber of consecrated space. Hence, as Aidan Hart has noted, threshold art can be called an art of the church atrium, but it can also be seen as an art of the narthex, so to speak, in which the catechumen is instructed, purified in metanoia and made ready for initiation into the Mystery of the incarnate Logos.

Discerning Spirits

As to be expected, there will be different degrees of success in actualizing the possibilities of a threshold art. Some attempt and fail, their work remaining relegated to, “ordinary, mental-corporeal life or those very things which constitute everyday circumstances of life.”[9] Whereas others succeed, without even trying to be “spiritual” or “religious” about things, nevertheless, it is clear that “the Divine beauty of invisible Divine things serves as the content.”[10] Therefore, we should always be cautious and test the spirits that guide an attempt at “joining together” with the Sacred, even if the work professes to be on the side of “the spiritual in art.” Are we in fact lead towards the Sacred or is it a demonic mirage, Satan appearing as an angel of light, or is it the embodiments of an unstable and disordered psyche that we behold? Is the artist himself getting out of the way or blocking the threshold to the inner sanctum? In testing the work of art we have the imprinting of the Divine beauty within us as a guide in our discernment. As St. Theophan the Recluse explains:

The spirit, which knows God, naturally comprehends Divine beauty and seeks to delight in it alone. The spirit cannot definitively prove what Divine beauty is, but by carrying within itself the design of it definitively proves what it is not, expressing this evidence by the fact that it is not satisfied by anything which is created. To contemplate Divine beauty, to partake of it and delight in it, is a requirement of the spirit and its life – the Paradisal life. Having received information about Divine beauty by means of its own mental image, it leaps with joy because within its realm it is presented with the reflection of that Divine beauty (delights), then itself devises and manufactures things in which it hopes to reflect it as it is presented to it (artists and actors). That is where these guests come from – delightful, estranged from everything sensual, elevating the soul up to the spirit and spiritualizing it![11]

But how about concrete works of art? We will perhaps never know the specific ones St. Theophan had in mind when he wrote these lines. Nevertheless, he further clarifies, in general terms, the class of works he thought of as exemplary in embodying the Divine beauty:

I would note that, concerning artistic works, I am including in this class only works in which the Divine beauty of invisible divine things serves as the content, and not those works which, although they are beautiful, all the same represent ordinary, mental-corporeal life or those very things which constitute everyday circumstances of life. The soul seeks not only what is beautiful, being guided by the spirit, but also the expression of the beautiful in beautiful forms of the invisible world, to which the spirit by its action beckons.[12]

In other words, here we are not speaking of beauty as merely the allure of seductive surfaces, the fetishism of artifice, or the idolatry of “that which pleases when it is seen” (id quod visium placet). No, here St. Theophan is rather channeling the patristic understanding of beauty as the splendor of the Truth, inseparable from the Good. His approach is philokalic, it bypasses the skin and enters into the ontological kernel of things, into the mysterious depths where the created meets the Uncreated. It is ultimately beauty having to do with deification. Thus if the work of art taps into and unveils this Divine beauty, if it becomes a disclosure of Truth, it can then become an instrument that beckons us to the Goodness of our ultimate destiny – theosis – participation in the divine nature. But I can almost hear some readers skeptically say, “Hah, here we go again with ‘Beauty will save the world’ talk!” The kind of knee jerk reaction I myself have at times when the cliché is thrown around.[13] Yet, I’m not willing to completely do away with the irrefutable formula of Truth, Good and Beauty, when it comes to questions of art, just because of the impetuous demands of fickle fashion. Without this first principle I fear everything is up for grabs and discernment compromised.

“Superstition”[14]

At any rate, it goes without saying that for many today, if not for most, this approach to art as described by St. Theophan is not convincing, being perceived as too limiting, naively religious, weak in its credulous idealism, and riddled with passé aestheticism. Has not art after all been liberated from the constraints of antiquated dogma and hopelessly arbitrary canons of beauty? Ours is an age that has canonized revolt, sacrilege, the creative genius, and other various myths of the avant-garde as orthodoxy. But the irony is that although the art world is wary about religion it persists in attempting to make of its galleries and museums “sacred spaces” of lofty emotions and aesthetic “contemplation”. And this is not surprising since, as we have said earlier, even secular man is homo religiosus and will continue to seek the Divine while simultaneously attempting to deny its reality. Yes, he unconsciously camouflages his true yearnings, refashioning old myths and heroes, rites and rituals, in the new artistic forms of pop-culture and “fine art”. Thus it is as if the faint memory of the traditional doctrine of art still persists in the postmodern art world, as a “superstition” (etymologically speaking, something that “stands over” from the past, and yet whose significance we fail to understand), since it will never be satisfied with art as an end in itself.

But what gives rise to our “superstitious” search for spaces of aesthetic “contemplation”? As we have said, according to the traditional doctrine meaning (symbolism) and function (utility) coincide, and art or techne is understood as a skill meant to supply for the needs of both soul and body. Techne found its raison d’etre in the revealed metaphysical principles that ordered the whole of an integrated traditional society. The so called, “Primitive man, despite the pressure of his struggle for existence, knew nothing of such merely functional arts. The whole man is naturally a metaphysician, and only later a philosopher and psychologist, a systematist. His reasoning is by analogy, or in other words, by means of ‘adequate symbolism.’ As a person rather than as an animal he knows immortal through mortal things.”[15] However, today, in our fragmentary postmodernity, in upholding the notion of “fine art” we undermine the utilitarian side, make of the work of art an end in itself and value it for its utter uselessness. So we oppose function to beauty, industry to art, work to contemplation, and no wonder why we are surrounded by so much ugliness and life becomes such a drudgery, lacking meaning and fulfillment. Without metaphysical grounding aimlessness prevails in the hustle and bustle of our rat race. For, “…in so far as we do now see only the things as they are in themselves, and only ourselves as we are in ourselves that we have killed the metaphysical man and shut ourselves in the dismal cave of functional and economic determinism.”[16] So who then is the “primitive”? Hence, seeking an antidote to the malaise, we begin to yearn for the gathering of our dispersed minds and senses in the haven of recollected inwardness, the regaining of our center, the union of heart and nous. Something to be found in prayer and contemplation for “the Kingdom of God is within you.”[17]

Wolfgang Laib, Pensatoio, 2009. Wax room, permanent installation, The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

So hoping to find relief from all the banality that surrounds us, as the consequence of so much “progress”, we attempt to infuse the “art for art sake” paradigm with the depth of meaning and fulfillment it lacks, bordering on religious conviction and devotion. The emperor might have no clothes but no one dares to question those who claim he does, those who have blind faith in the meaning of something utterly meaningless. Yes, all of this points to the unavoidability of an unconscious yearning to see art fulfill its highest function, the joining together of the realm of culture with the Divine. But, as the saying goes, “you can’t have your cake and eat it too.” The postmodernist art world at once shrugs off, demythologizes, deconstructs, and tramples on Tradition along with its so called meta-narratives, while still hoping somehow to accrue the benefits of its vestiges, still lingering unconsciously in the collective memory as a “superstition”. Noticing this cognitive dissonance in the art world a contemporary art critic, writing for Frieze Magazine, tells us: “Art is a faith based system that, to paraphrase philosopher Simon Critchley, ‘combines an uneasy godlessness with a religious memory.’ Religious conviction is taken to be a sign of intellectual weakness, and yet meaning in art is itself often a question of belief.”[18]

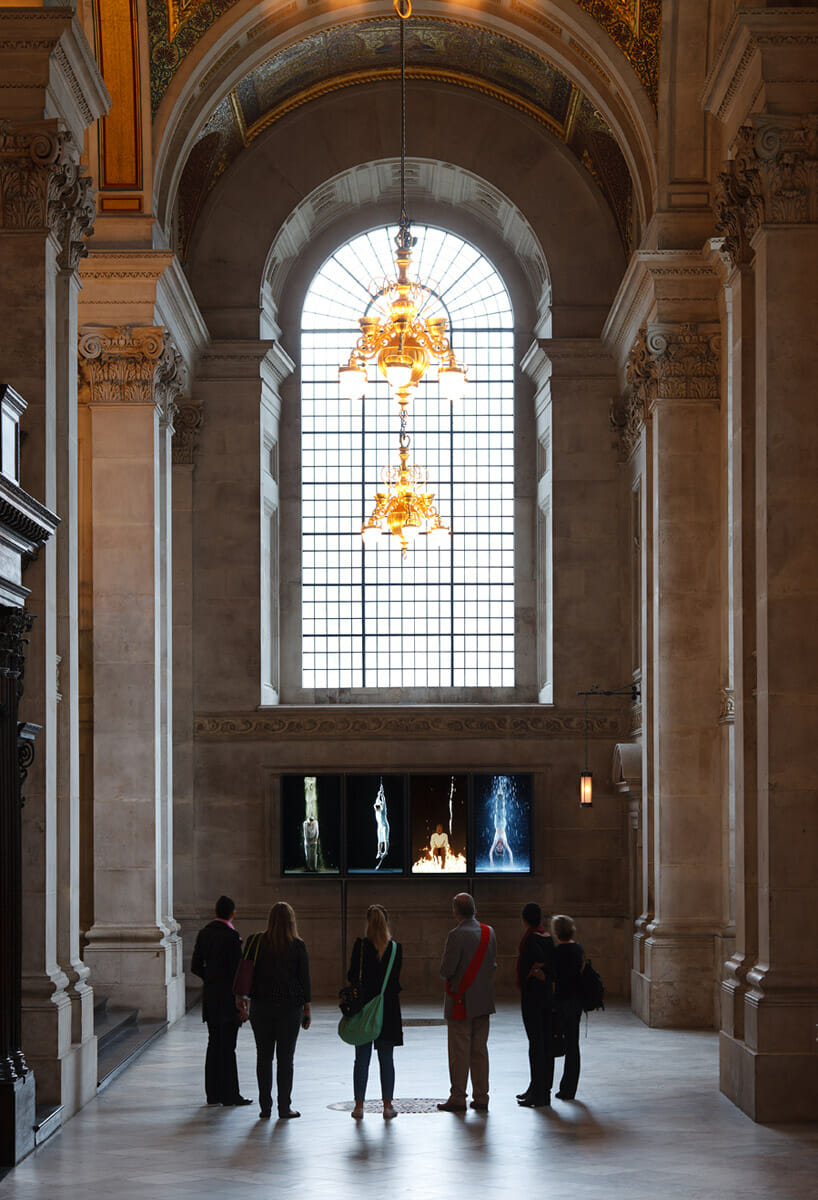

Bill Viola (with Kira Perov), Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water), 2014. Video installation, St Paul’s Cathedral, London. The first moving-image artwork to be installed in a British cathedral or church on a long-term basis.

In denial of this cognitive dissonance, the search continues for deep, ultimate content, even so-called “spirituality”, while reveling on vagueness and relativistic ambiguity, avoiding at any cost revealed, clear and vetted metaphysical principles grounded in Reality. Yes, postmodernity dreads claims of unicity in the realm of religion and would rather opt for a truth denying pastiche of doctrine, a syncretic contradiction passed off as logic. Thereby it inflicts intellectual violence on various traditions in the name of “open minded” tolerance and justice. Hence, for those who have faith in “art”, there is no reason to believe that the extravagant – at times even lewd – performances at the “sacred precinct” of the gallery shouldn’t be as, or in fact, even more spiritually efficacious than the boring services held in dying churches. So, some might say, “Isn’t the gallery just another form of “refined” and “lofty” entertainment?” Then again, wouldn’t the devout contemporary gallery goer say the same about the “up to date” media spectacles, played out in the multicolored lit stages of the mega churches?

Be that as it may, the earnest and curious crowds flooding the exhibitions in the “sacred precinct” of the gallery tend to remind me of those who gathered at the Areopagus in Athens, spending “their time in nothing else but either to tell or to hear some new thing.” The truth or falsehood of the thesis expressed by the work of art no longer matters, as long as the senses and vain curiosity are gratified, or the exhilarating rush of shock is to be had. Unrestrained “freedom of expression” becomes the sole criteria. The artwork becomes just another bill board, a publicity stunt, the artist thereby hoping to accrue market value and his fifteen minutes in the spotlight. One concept topples the next as the most relevant theoretical, philosophical or political position of the day; one after another ad infinitum, but, ironically, at the end of the day mere sentimentality and bad taste prevail, after the rationalism that gave them birth. “Art” then becomes, as St. Nicholai Velimirovich puts it, “a mask of vanity.”[19]

The Temenos

But, we should not be too quick to despair over this seemingly bleak predicament. As much as we might want to feel justified in throwing stones we should be cautious and see if perhaps we are doing so from glass houses. Perhaps all of the symptoms just described are the consequences of a European Christian civilization that has taken a wrong turn. It might in fact be the result of Christian heresy, a flawed epistemology and anthropology arising from theological aberrations and deviation from Tradition ̶ that is, from Eastern Orthodoxy. In any case, Aidan Hart touches on the matter from a slightly different angle, holding Christians as partly responsible, while pointing to the positive, threshold potential of gallery art:

Gallery art as distinct from sacred or liturgical art is here to stay, and when at its best it enriches our lives. Though not art of the altar, it can function as art of the threshold, art of the atrium (the paradisiacal forecourt in front of the entrances to ancient churches). Because Christians have failed to live up to the Gospel, many people have abandoned belief, even belief in a personal God. Perhaps therefore the first step towards a return to Christ is to help people become good pagans so they can become good Christians. The art gallery has become the temenos, the sacred precinct to which people go in droves to find meaning.[20]

This would then be the context for the Orthodox artist not yet called to the practice of a liturgical art. Thus his vocation would consist of fearlessly pointing out the “altars to the unknown God” in the midst of the temenos; to find common ground with the “pagan” who unconsciously pursues the incarnate Logos. Through his art he will gently and humbly point out how faith in the “superstition” of “fine art” only betrays an innate desire for the primordial Tradition. His task will be to aid in bringing about within the temenos a metanoia, a change of mind, a rite of passage leading to the threshold of the Sacred.

However, in the battle that will inevitably ensue the risks will be many and the cost is high – nothing other than self-sacrifice. In his arduous task he will have to continually remind himself that, in spite of all the “idols” he sees around him in the temenos, gallery art can, in its best moments, surmount the limitations of individualism; call us to compassion and offer hope as it addresses suffering; tap into our ontological depths; spur us towards the realization of our true logos or meaning; remind us of the delights of Paradise; reveal the mysterious kernel, the divine beauty and order of Creation; unveil the Cosmos as a theophany, etc. Yes, these might be exceptions that prove the rule, anomalies, so to speak, of a gifted few in an otherwise seemingly unredeemable predicament. Nevertheless, rare though these moments can be, they are still possible and worth pursuing as antidotes to the general malaise. In fact, there is no doubt that these moments attest to the intervention of the Spirit. As Philip Sherrard puts it:

…An artist whose intention and attention is concentrated on the discovery and expression of spiritual principles within and without (and this, must presuppose his acceptance of a metaphysical view of the universe) may well be given moments of revelation and illumination, intimations and intuitions of eternity, and so transfigure the material of his art with that beauty and rhythm which are the hallmark of the sacred. To affirm this is not to suppose, in a way that is fashionable, that the artist enjoys some special status that exempts him from conditions that apply to ‘ordinary’ human beings, and so from the need to practice spiritual discipline. Yet to deny it would be to deny not only the freedom of the Spirit to blow where he will but also the testimony of those works of art produced during the last centuries – relatively few though they may be – that communicate such beauty and rhythm in spite of the fact that their creators have lived outside the framework of formal religion.[21]

In other words, it would be foolish for the Orthodox artist, under the pretext that the Spirit blows where it wills, not to avail himself of the vetted spiritual principles contained within his religious framework, as guidelines that can help transform his art into a threshold of the Sacred within the temenos.[22] But if he is to transfigure his art he must be also working on transfiguring himself.

Antony Gormley, Sound II, 1986. Sculpture, metal statue standing in flooded crypt, Winchester Cathedral, England, UK.

Ascesis

Indeed, as Sherrard emphasizes, to actualize this transfiguration spiritual discipline is indispensable. Moreover, it is not sufficient to solely rely on human effort to attain illumination. The artist’s “eye of the heart”, his nous, must be purified through initiation into and sacramental participation within Tradition. For it is incumbent upon him to deliver from the resources of his experience, stemming from life in the Spirit. “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.”[23]Only to the measure of his purity of the heart will he begin to see the Sacred in all created beings, and apprehend them as objective and polyvalent symbols – icons of God. Hence he will be peering into the structure of reality itself, its true meaningful order and purpose. His work will then become nothing other than a lucid reflection of the infinite radiances of the Logos, attesting to an ordered and harmonious state of soul. Hence, through its beauty, it will in turn assuage other souls from trouble and disorder.[24] In the words of Dante, his art will help to “remove those who are living in this life from a state of wretchedness and to lead them to the state of blessedness.”[25]

But most have eyes and yet fail to see the theophany. The waft of the sweet fragrance of the Sacred is accessible to all, to be enjoyed in pure reverie, but “can only be understood by those whose spiritual sight is opened to such a degree that they are able to see by the spirit the spiritual meaning of everything, but not by those who gaze with physical eyes and see only the physical nature of things.”[26] Therefore, few comprehend St. Peter of Damaskos when he says, “…God’s goodness and wisdom, His strength and forethought, which are concealed in created things, are brought to light by man’s artistic powers.”[27]

This is a reality most contemporary artists tend to ignore or completely deny, even when in pursuit of the “spiritual in art”. But if the “spiritual in art” is sought, we should be careful not to confuse it with the psychic realm, that is, the lower dimensions of what St. Paul calls “soulish man,” whether it be his passions or seething emotions, dreams or subconscious, discursive reason or ratiocination. In other words, the “spiritual in art” pertains to man’s higher, supra-rational faculty, his spirit or nous, and its illumination through the grace of the Spirit in the overcoming of egoic inclinations. In the non-liturgical sphere the subjective orientation will inevitably tend to be prevalent, wherein art becomes a kind of laboratory of creative experimentation and exploration. So the aim is to keep, by the guidance of the illumined nous, the lower and disordered movements of the soul from becoming the sole determining factor, or completely overwhelming artistic form. Thereby the work will be more than just an exhibitionism of unrefined emotions, or a cold conceptualism, mistaken for spiritual insight. In this respect it can be said that the creative act of both the liturgical artist and non-liturgical artist engaged in threshold art will converge. In other words, both will be pursuing the mean between extremes, which according to St. Gregory of Nysa is nothing other than the path of virtue.[28]

It goes without saying that it will take more than merely duplicating ancient religious symbolism, arbitrarily extracting them from their original cultural context, in which they served to express the communally accepted metaphysical worldview of an integrated society. His visual language must resonate with his audience and without compromise take account of the contemporary artistic discourse. So the point is not to embark on a campaign of Christian propaganda, in order to emotionally manipulate the masses and sell them an ideology. Neither are we proposing moralistic subject matter and didactic themes as an alternative. Nevertheless, with his new symbolic language, whatever form it takes (and here is where a major part of the creative challenge lies), he will still have to somehow, “…make the primordial truth intelligible, to make the unheard audible, to annunciate the primordial word, to illustrate the primordial image …”[29] That is, he will be engaged in a poetic unconcealment of the presence of the Logos– the hypostatic Truth. This then will become his doxology and sacrifice, a liturgical creative act in a non-liturgical sphere. He will then be confronting the iconographer with oneness of mind; the one from the narthex towards the nave, while the other from the nave towards the narthex, in the threshold of the Sacred.

Conclusion

Throughout these series of posts we have looked at the tension between Tradition and cultural temperament, the traditional doctrine of art, the clashing of artistic paradigms and the challenges we face ahead, both in the realm of liturgical and non-liturgical art. The brief observations we have made here only scratch the surface of all the very complex issues surrounding the seemingly inexhaustible topic of “art”. Nevertheless, they will hopefully contribute to awaken us from the stupor of misconceptions we so often take for granted as sacrosanct truths. As we have seen, the icon, and the traditional doctrine of art that it represents, serves as an efficacious contrast and gauge in discerning the symptoms of our contemporary artistic malaise. It calls us to come to an awareness of the metaphysical principles our culture has cast aside, and the presuppositions we have installed in their place, without even realizing it. Presuppositions that have brought us to what some have called “the end of art.” As Andrew Louth succinctly puts it, “…The truth is rather that if icons are art, then this poses questions about the very nature of art that are quite different from those that have come to be taken as fundamental in the experience of the West.”[30]

The Orthodox non-liturgical artist, hoping to make of his art a “threshold” of the Sacred, will not be able to ignore that the fundamental premises of contemporary art are in fact a revolt against Tradition, or at least its distorted representatives in Western civilization. Moreover, his art must consist of something more than just a superficial pasting of a Christian message on aesthetic forms which in fact end up negating the very message.[31] Ironically, he must somehow subvert the premises of contemporary art, mainly its suspicion of anything having to do with religion, and revolt against the individualistic humanism, hedonism, skepticism, ugliness, materialism and relativism of postmodernity. And if he is to ward off the cynicism, irreverent irony and nihilism of our profane cultural context, it is crucial to continually call to remembrance through his work the possibility of redemption and take into account man’s ultimate calling and intended destiny– theosis. In so doing he will be treading a solitary ascetic path of uplifting culture to a higher purpose, rather than pandering to and conforming to its distortions.

So this challenge is ultimately not solely about aesthetics, but, as noted earlier, one having to do with personal transformation, a rebirth, which can begin as soon as the artist is willing to present the gift of art back to the Divine Craftsman in self-sacrifice. For, as Andrey Tarkovsky, who sought to make of his art a threshold, puts it, “The artist is always the servant, and is perpetually trying to pay for the gift that has been given to him as if by a miracle. Modern man however, does not want to make any sacrifice, even though true affirmation of the self can only be expressed in sacrifice…”[32]

William Blake, Mary Magdalen at the Sepulchre, 1805. Watercolor with pen and black ink and gray ink on medium, moderately textured, cream wove paper, 17.24 in. x 12.24 in.

Notes:

[1] Our bracketed clarifications. A. K. Coomaraswamy, “A Figure of Speech or a Figure of Thought?” in: The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, R. Coomaraswamy (ed.), Indiana, World Wisdom, 2004, p. 40.

[2] N. Gogol, extract from a letter to the poet Zhukovskii, I January, 1848.

[3]P. Sherrard, The Sacred in Life and Art, Evia, Denis Harvey, 2004, p. 16.

[4] A. Tarkovsky, “Art – A yearning for the Ideal”, in: Sculpting in Time: Reflections on Cinema, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1998, p.38

[5] Ibid.

[6] On the “sacramental” implications of art see David Jones, “Art as Sacrament,” in: Every Man an Artist: Readings in the Traditional Philosophy of Art, Brian Keeble (ed.), Indiana, World Wisdom, Inc., 2005, pp. 141- 169.

[7] As Aidan Hart notes: “Art’s literal meaning is to join together fittingly (from the Latin ars). It is not therefore surprising that the natural desire to recreate and rediscover the pristine unity of man and the cosmos will be expressed through art. Most art as we know it is really this cry of nostalgia for Paradise lost.” A. Hart, Beauty, Spirit, Matter: Icons in the Modern World, Leominster, Gracewing, 2014, p. 138.

[8] Likewise, as Aidan Hart notes, “Whereas sacred iconography is a fruit of Eden rediscovered, art can be seen as the fruit of Eden sought for.” A. Hart, op cit.

[9] St. Theophan the Recluse, The Spiritual Life and How To Be Attuned To It, Safford, St Paisius Serbian Orthodox Monastery, 2003, p. 56.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] As Solzhenitsyn put it, “It is vain to affirm that which the heart does not confirm . . . a work of art bears within itself its own confirmation: concepts which are manufactured out of whole cloth or overstrained will not stand up to being tested in images, will somehow fall apart and turn out to be sickly and pallid and convincing to no one. Works steeped in truth and presenting it to us vividly alive will take hold of us, will attract us to themselves with great power—and no one, ever, even in a later age, will presume to negate them. And so perhaps that old trinity of Truth and Good and Beauty is not just the formal outworn formula it used to seem to us during our heady, materialistic youth. If the crests of these three trees join together, as the investigators and explorers used to affirm, and if the too obvious, too straight branches of Truth and Good are crushed or amputated and cannot reach the light—yet perhaps the whimsical, unpredictable, unexpected branches of Beauty will make their way through and soar up to that very place and in this way perform the work of all three…And in that case it was not a slip of the tongue for Dostoyevsky to say that “Beauty will save the world,” but a prophecy.” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, “Beauty Will Save the World: The Nobel Lecture on Literature,” 1970. As quoted by V. Gabriel in: The Beauty of Logos: Towards an Orthodox Aesthetic, http://blogs.ancientfaith.com/onbehalfofall/the-beauty-of-logos-towards-an-orthodox-aesthetic/#fnref-12938-1, 2014 (accessed 2016).

[14] See S. Cross, “The Arts- A Superstition of our Time?”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fTRNXbUJxZQ, 2012 (accessed 19 April 2016).

[15] A. K. Coomaraswamy, “Art Man and Manufacture,” in: Our Emergent Civilization, R. N. Ashen (ed.), New York, Harper & Brothers Pub., 1947, p. 157.

[16] Ibid., p.158.

[17] Luke 17:21.

[18] D. Fox, Believe it or Not: Religion Versus Spirituality in Contemporary Art, Frieze Magazine, Issue 135, November-December, 2010. http://www.frieze.com/issue/article.believe-it-or-not/, 2010 (accessed 19 April 2016).

[19] N. Velimirovich, “The Agony of the Church”, http://www.monachos.net/content/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=696&catid=34&Itemid=65, (accessed 19 April 2016).

[20] A. Hart, op. cit., p.191.

[21] P. Sherrard, op. cit., p. 40.

[22] As Aidan Hart notes, “In order not to lose their bearings, perhaps artists working in the threshold area need also to be active – or at least have very close links with – sacred art. It would help their art to remain an albeit subtle expression of the beauty of the altar and nave, since their dominant personal experience was that of divine culture rather than fallen culture.” From our private correspondence, Apr. 23, 2016.

[23] Matt. 5:8.

[24] N. Gogol, op. cit.

[25] Dante, “Divine Comedy,” as quoted by S. Bucklow, The Alchemy of Paint: Art, Science and Secrets From the Middle Ages, London, Marion Boyars, 2009, pp. 211-12.

[26] N. Velimirovich, The Universe as Symbols and Signs: An Essay on the Mysticism of the Eastern Church, South Canaan,/ Waymart, St. Tiokhon’s Seminary Press, 2010, p.10-11.

[27] St. Peter of Damaskos, “The Sixth Stage of Contemplation”, in: The Philokalia Vol. III, G. E. H. Palmer, P. Sherrard, K. Ware, London, Farber & Farber, Inc., 1984, p.137.

[28] Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses, II, 289

[29] “To make the primordial truth intelligible, to make the unheard audible, to annunciate the primordial word, to illustrate the primordial image – such is the task of art, or it is not art.” Walter Andrae, Die ionische Saule, Berlin, 1933, p. 65.

[30] A. Louth, “Orthodoxy and art”, in: Living Orthodoxy in the Modern World, Crestwood, SVS Press, 1996; as quoted by Susan Cuchman in: “The End of Art”, http://susancushman.com/the-end-of-art/, 2008 (accessed 19 April 2016).

[31] See J. Pageau’s lecture, Sacred Symbol, Sacred Art, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l5Gfcuu-X7I, 2015 (accessed 21 April, 2016).

[32] A. Tarkovsky, op. cit.

Fr. Silouan, Just wanted to let you know how much I have enjoyed and learned from your last two articles! You write as well as you write icons!

Thank you Dianne. Christ is Risen! Happy you enjoyed the articles.

+

Christ is risen!

Fr. Silouan, great article. I have to go back and read it again since I just sped through it at work ^_^.

That being said, this issue has been on my mind lately given that my painting process is half traditional half digital. It actually started with the article featuring the interview with Stephane Rene, where he expressed his dislike for digital artists pretending to be iconographers.

While I clearly see the line and difference between an icon and digital illustrations of saints, it makes me wonder if this work I’m doing is of any value. Putting the goal of the service aside (which is to engage today’s youth on social media using these timely quick-to-produce illustrations to help them live the church calendar throughout the week), it feels like I am better off taking the time to learn iconography and paint proper icons.

I’m still not at peace with this idea, but this article is helping me sort it out in my head, there is still hope! There might yet be spirit in illustrations. 😀