Similar Posts

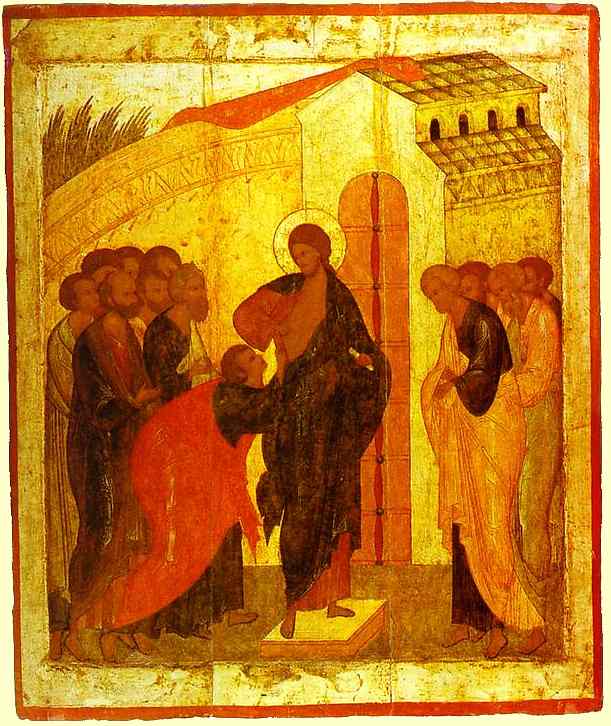

The materiality of the icon affirms the reality of the Incarnation, but in the icon we do not only see, but also touch the Word of life. In the words of St. John the Theologian, “That which was from the beginning, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon, and our hands have handled, concerning the Word of life…”(I John 1:1)

Half the Icon, Subtle Docetism

We often hear that only the image matters since veneration of the

image ascends to the prototype. However, this considers only half

the icon. As St. Theodore says,“its not admissible to call

something a prototype if it does not have its image transferred into

something material.Therefore, since we confess that Christ has the

relation to prototype, like any other individual, He undoubtedly

must have an image transferred from His form and shaped in some

material. Otherwise He would lose His humanity,if He were not

seen and venerated through the production of the image.”54

Abstracting the icon as a purely visual or ocular “image”

disembodies and truncates its theological implications and

overlooks the crucial role of matter in the Incarnation.We risk

sounding like those who said, “It is sufficient that He should remain

in mental contemplation.”55 St.Theodore said it is crucial that:

“ … we depict His human image with material pigments. If merely mental contemplation were sufficient, it would have been sufficient for Him to come to us in a merely mental way;and consequently we would have been cheated by the appearance both of His deeds, if He did not come in the body, and of His sufferings, which were undeniably like ours. But enough of this! As flesh He suffered in the flesh, He ate and drank likewise, and did all other things which every man does, except for sin.”56

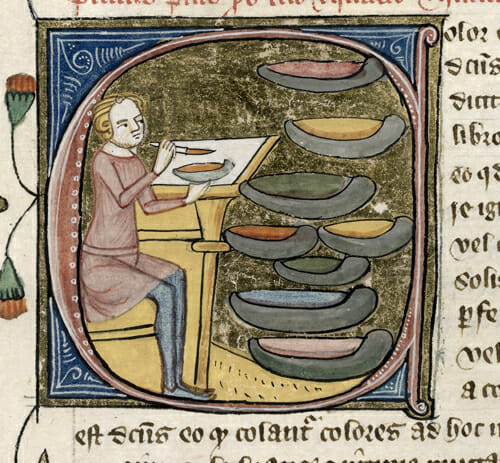

Medieval writings assume a regard for the individual characteristics, or “glory,” of each individual pigment, regarding them as jewels harmoniously arranged in a complicated setting.

Approach to Materials

Ingredients given by the Creator best communicate the icon’s

symbolic message.They confer a beauty not attainable through

synthetics: “For from the greatness and beauty of created things the

Creator is seen by analogy.”57 When synthetics are unavoidable or

advantageous, it is incumbent on the iconographer to ensure that

they not disrupt the harmony or theology of the icon. It is naïve to

deny that craftsmanship involves “technology.”The craftsman

alters and shapes raw materials.This either degrades or uplifts

matter, depending on the craftsman’s inner state and his awareness

of the Sacred in all things. Emphasizing the importance of

hand-made icons is not a matter of disdaining technology per se,

but rather is about how to discriminate among technologies and

discern their appropriate use. It should also be noted that the terms

“natural”and “artificial”are fluid.“Artificial”pigments are

usually taken to be dead, flat,or garish, but traditionally

manufactured “artificial”pigments have a subtlety and beauty of

tone that render them “natural”in comparison to contemporary

products. Compare Chinese Vermillion to Cadmium Red.The tone

of the first,though bright,is gentle in effect, while the second

tends to be too bold and harsh. Nature’s unmatched beauty is in its

imperfection, while the ugliness of manufactured materials is in its

monotonous uniformity. We tend to conceive of color as a

disembodied, flat film– a chemical byproduct lacking texture or

character. Traditional icon painting values each pigment‘s nuance:

its particle size, coarseness, or smoothness.The icon painter

decides how to grind pigments to obtain the desired texture and

allows materials to manifest inherent qualities by not tampering

with them.The traditional attitude to the “glory”of each pigment,

coming from an awareness of the sacramental dimension of matter

and craft, clearly seen in the medieval workshop, is described by

Daniel V. Thomson:

“In modern painting methods, subtle differences in the characters of

pigments tend to be submerged. In oil painting it does not make very

much difference in the effect whether the painter uses an earth red in

its natural register or forces a bright red down in key to match the

earth red in color. Modern oil paint has so much [subsidiary]

material in it besides pigment that the pigment hardly has a chance

to show its individual character.In medieval painting methods,

however, the separate pigments tend to be exhibited with emphasis,

almost like jewels in a complicated setting. Fine colors were so hard

to come by in the Middle Ages that the painter would not willingly

degrade them by indiscriminate mixing. The palette was treated

almost like a collection of precious stones, to be grouped in the

painting with as much regard for their intrinsic beauty as possible.

And the media in which it was applied gave full play to the

individualities of the pigments; for they were unobtrusive in

themselves. Medieval writings assume a regard for pigment

characters, an interest in the fatness or leanness, coarseness or

fatness,transparency or opacity, of each separate pigment…The

medieval painter was aware of the special qualities of his particular

colors as a musician of the special qualities of instruments and

voices.”58

Notes:

54St. Theodore, op. cit., p.112.

55Ibid., pp.26-27.

56Ibid.

57Wisdom of Solomon 13:5.

Great article! I wish that it had been around about 6 years ago when having arguments with various lecturers, tutors and professors when I was at University. Whilst the spiritual elements may have been disregarded by many of them but the article raises many cogent points. Thanks for posting the article.

Yes, a very important article indeed. For years I have been frustrated with folks who learned about icons from iconologists, and who see them as image-compositions only. It seems iconologists, who like to “decode” icons and treat them as semiotic collections of signs and hidden meaning, are only able to appreciate them as images in the abstract. This is deeply wrong. All of the symbolic colors and gestures could be missing, and a good icon would still be a good icon, because its iconicity lies in the representation of a holy face with beautiful craftsmanship.

Academia in general is prone to this semiotic bias, no doubt simply because academia is full of people whose talents lie in reading and writing, not in material crafts. I majored in art history, and until 20 years ago, art historians treated all forms of art with this type of image bias. Recently, they have begun to show understanding of the material reality of art. The Getty Museum show of the Sinai icons was very progressive in this regard. Some of the secular curators of that show had a much richer understanding of those icons than any Orthodox ‘iconologist’ I know.

While I am deeply sympathetic to this article the Holy Ecumenical Fathers decree that it is indeed the image qua image that pertains to the prototype: that would imply a projected image remains worthy of veneration.