Similar Posts

MOSAIC OF CREATION – St. Marks, Venice.

“Then God saw everything He made, and indeed, it was very good.” Gen. 1:31.

Mysteriological Matter

Let us now digress for a moment to consider some aspects of the icon as symbol and mysteriological object, for these will further elucidate the materiality of the icon and how it bears on mechanical reproductions. St. Theodore reminds us that, though not becoming mixed or one in nature,33 “The prototype and the image have their being, as it were, in each other … .”34 The icon is not merely a sign that points to the idea of Christ.Rather, it is, as a mysteriological reality, a symbol linked to Him,a true manifestation, or “ekphansis” (out-appearing),of the Prototype.Through material depiction we encounter the true presence of Christ. Since in the incarnate Person of the Logos there is a “union without division or confusion” of divinity and humanity, in venerating His material icon we paradoxically kiss and handle divinity. As St. John of Damascus says,“God‘s body is God because it is joined to His person by a union which shall never pass away.The divine nature remains the same; the flesh created in time is quickened by a reason-endowed soul. Because of this I salute all remaining matter with reverence, because God has filled it with His grace and power.”35

The icon is a border between the created and Uncreated. As symbol it functions as a veil, simultaneously concealing and manifesting the divine mystery.36 A veil is pressed upon, moved, and unfurls in multifarious ways by the energy of a gust of wind. Through it we see the unseen.Take the veil of matter in creation a way and the divine is no longer perceived; we no longer have a theophany.The cosmos is an icon, an incarnation in a lower level, before the Incarnation. In the Incarnation,we find the deification of matter, the transfiguration of the fallen cosmos, and the re–attainment of its incorrupt primal beauty. In a variety of ways and levels, matter thus becomes grace bearing in the life of the Church. It becomes a foretaste of the restitution of all things in the Eschaton when God will be“all in all.”37 As a mysteriological object,the importance of the material side of the icon should not be underestimated or undermined by considering as inconsequential the materials we employ in their fashioning, because they will become vessels of divinity. The paradoxical interdependence of the material icon and Prototype is to be maintained. As St. Theodore stresses, “With the removal of one the other is removed, just as when the double is removed the half is removed along with it. If, therefore,Christ cannot exist unless His image exists in potential, and if, before the image is produced artistically, it subsists always in the prototype: then the veneration of Christ is destroyed by anyone who does not admit that His image is also venerated in Him.”38 Remove the material icon and we no longer see, kiss, or touch God.

It then starts to become clear that not just any kind of material suffices to carry out the icon’s most sacred function of “paradoxical interdependence.”The dynamics of image and prototype that we have just mentioned are not undone in a mechanical reproduction, nor are they deprived of grace. Mechanical reproductions remain icons and therefore retain their status as mysteriological objects. Yet, as will be further elucidated,they compromise the dignity of worship and erode the aesthetic experience of liturgy by disregarding, and therefore distorting, the icon’s multiple levels of function: anagogic, symbolic, and paradoxical interdependence. In so doing they degrade iconicity.

MOSES ON MOUNT SINAI.

“See that you make all things according to the pattern shown you on the mountain.” Exodus 25:40.

After the Pattern: As Above, so Below

In selecting materials, there should be an awareness of how their inherent properties relate to the factors just mentioned, how they affect us and the worshiping environment.These properties will either impede our worship of, and encounter with,God or they will facilitate it. They will either glorify Him or fail to. As vessels of His presence, icons demand of us generous investment. Only the best should be brought as sacrifice and offering for liturgical service.We are told of Solomon that when he was building the temple, “he decorated the house with precious stones for beauty ... .”39 Tradition teaches us to select the most precious, organic, and natural materials available. As the clearest reflections of heavenly Beauty, these materials greatly aid the soul to become a sanctuary of prayer and worship.40 We read in the book of Exodus:

“And the Lord spake to Moses, saying, speak unto the children of Israel, that they bring me an offering...gold and silver and brass…and blue and purple… and ram skins dyed red, and badger‘s skins, and shittim wood, oil for the light, spices for anointing oil, and for sweet incense…Onyx stones, and stones beset in the ephod, and in the breast plate…and let them make me a sanctuary; that I may dwell among them.”41

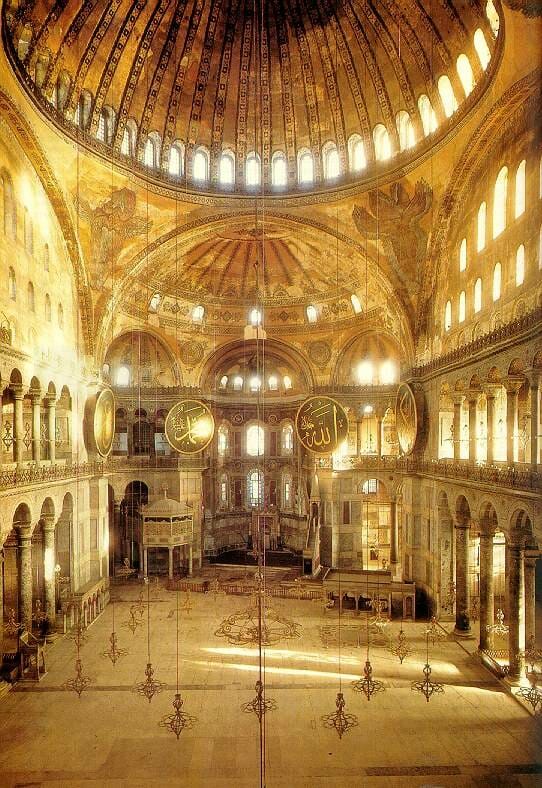

These materials were divinely chosen as symbols and types and as the ones most fitting for the habitation of the Lord‘s presence, the Tabernacle of Witness. They serve as models for us in considering what kind of materials are fitting for liturgical use, some of which we find still being used today. Upon the completion of Hagia Sophia, St. Justinian is said to have exclaimed, “Solomon I have surpassed you … .” Hagia Sophia might be the ideal of liturgical aesthetics, but this wonder was the culmination of centuries of artistic development.The main models the Church has used to arrive at this clarity of expression are the Tabernacle of Witness and the Temple of Solomon. In the book of Chronicles we are told of the materials David collected for the temple Solomon was to build, a passage which serves as a pattern of voluntary sacrifice and desire to offer the best for the house of God:

“According to all means possible I prepared gold, silver, bronze, iron, wood, onyxstones, costly and precious stones of various colors, and much marble for the house of my God. And because I took pleasure in the house of my God, I gave to the house of my God gold and silver over and above what I procured for myself; more than all I prepared for the house of my God, over and above all I prepared for my consecrated house. Three thousand talents of refined silver to be overlaid in these walls of the sanctuary by the hands of craftsmen ... .”42

In this passage we also encounter the important role of the craftsman who would mediate between the king and the Lord through his inspired skill, transforming the raw materials provided and offering them back as a sacrifice of praise. As Solomon is about to build the temple, he also summons the craftsmen from Hiram, king of Tyre, and enumerates the materials that were to be used to glorify God:

“Who am I, then, to build a house, except to burn incense before Him? Therefore send me at once a wise man skilled to work in gold and silver, in bronze, and iron, in purple and crimson and blue, who can work skillfully with the skilled men with me in Judah and Jerusalem,whom David my father provided. Also send me cedar and cypress and pine timber from Lebanon, for I know that your servants are skilled … .”43

VIA LATINA CATACOMB.

The Church always sought to transform through art drab and mundane environments.

Recall that the Tabernacle was to be constructed after “the pattern” shown to Moses on the mountain and was therefore anagogic in function.The Tabernacle pattern was modeled after the Church (i.e., the “good things to come”), which in turn is an image of the heavenly dispensation. The Church has worshiped in dark caves and catacombs and this has not deprived Her of the riches of liturgical worship. Nevertheless, even under such circumstances it always sought to transform through art the drab and mundane environments it was constrained to inhabit.The Church sought, in the words of Dante, to “remove those who are living in this life from the state of wretchedness and to lead them to the state of blessedness.”44 Once it was free of persecution, the Church was unhindered in its aspirations to make of the worshiping environment a reflection of the Heavenly Jerusalem. In doing so, it has always offered the best of creation back to God in the arrangement and decoration of His temple, considering this a gesture of sacrifice, devotion, and glorification.This has not been done haphazardly, or solely for the sake of vacuous embellishment. Rather, it intends that beauty be used to make the worshiping environment the most conducive to prayer and worship. Everything is arranged to make a sacred space set apart from the mundane, where earth and heaven come together, the faithful encounter the Church Triumphant, where the unseen, past, and coming events of the divine dispensation become present through the various liturgical arts. All of this takes into consideration the engagement of the five senses and our interaction with the icon as a concrete object, affecting us with its energies, both material and uncreated. It remains to be seen how the reproduction fits into this context.

Thus far, we have looked at the contemporary cultural context from which the mechanical reproduction arises as a symptom of a world of consumerism and simulacra. A definition of the idea of “bodies of glory” has been given as a key factor in liturgical aesthetics and the anagogic dynamic that unfolds therein. Part of this dynamic also involves symbolism and the icon as a paradoxical “border” between the created and Uncreated. All of this has enabled us to consider the materials in the liturgical context based on a traditional mindset. Let us now examine some aspects of the icon’s craftsmanship, its “process of shaping,” or how it “comes into being.”

Notes:

33St. Theodore maintains the “difference in essence” between the prototype and icon saying ,“We speak of relation inasmuch as the copy is in the prototype; one is not separated from the other because of this, except by difference of essence. Therefore, since the image of Christ is said to have Christ‘s form in its delineation, it will have one veneration with Christ, and not a different veneration.” St. Theodore the Studite,On the Holy Icons, Third Refutation of Iconoclasm,SVS Press, Crestwood, N.Y.,1981, p.106.

34St. Theodore the Studite, Ibid.,p.110.

35St. John of Damascus, op. cit., p.23.

36“In early Christian language, sacramentum or mysterium was applied to any sacred action or object, in fact to anything which as mirror or form of the Divine was regarded as revealing theDivine.The number of ‘mysteries’ is therefore potentially limitless, for every thing in the cosmos in some manner mirrors or enforms the Divine, and is thus a mysterium.” P. Sherrard, The Sacred in Life and Art, DeniseHarvey (Publisher), Evia, Greece,2004,p.22.

37As Metropolitan Kallistos explains, “God has ‘deified’ matter, making it ‘spirit–bearing‘; and if flesh has become a vehicle of the Spirit, then so—though in a different way—can wood and paint.” He also clarifies,“… [W]hen we talk of ‘seven sacraments’, we must never isolate these seven from the many other actions in the Church which also possess a sacramental character, and which are conveniently termed sacramentals.… Between the wider and the narrower sense of the term ‘sacrament‘ there is no rigid division: the whole Christian life must be seen as a unity, as a single mystery or one great sacrament, whose different aspects are expressed in a great variety of acts, some performed but once in our life, others perhaps daily.” T. Ware, The Orthodox Church, Penguin Books, London, 1997, p.33 and p.276.

38St. Theodore, op. cit., p.110.

392 Chron.3:6.

40In summarizing St. Dionysius, Eric D. Perl says: “Since form is beauty, and the formal determination in each thing is God in it, therefore the beauty in each being is God in it.”E. Pearl, Theophany:The Neoplatonic Philosophy of Dionysius the Areopagite, SUNY Press, Albany, N.Y., 2007,p.43.

41Exodus 25:1–8.

42IChron. 29:2–5.

432 Chron.2:5–7.

44Dante, Divine Comedy, as quoted by S. Bucklow,op. cit., p.209.

This discussion is both sophisticated and convoluted. But scripture

expressly says “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image either of things above or of things below…” It says, further,

“God is a spirit, and those that worship Him must worship Him in spirit and in truth.” Kissing and handling icons seems to me

blasphemous; they may purport to represent spiritual entities that no human has ever seen, but this is simply the idolatrous human imagination at work.

Dear Vivienne, please compare your comments above) to the Gospel: “Any spirit that does not confess that the Christ has come in the flesh is antichrist.”