Similar Posts

Markos Kampanis at work on the murals of the Convent of the Virgin Mary at Kornofolia in Evros, Greece.

We often forget that our contemporary art, although the offspring of the 20th century revolutionary avant-garde, has its own set of artistic dogmas, its form of “orthodoxy”, so to speak. Ironically, although the avant-garde might have shattered the stifling shackles of the Academy, it has now itself become another form of restrictive academy, forming an inextricable ideological component of our galleries and museum institutions. So it is understandable how an artist, seeking a niche within the cutthroat competitive world of contemporary art, would feel the pressure or compelled to conform to the demands of the main stream gallery market and its dogmatic, postmodern critical discourse. In this scenario the brave ones go against the grain and define their own terms independently, without pandering to the establishment.

To pull off such a feat of artistic independence might seem untenable, almost a recipe for career suicide, but I would rather call it a heroic sacrifice. Markos Kampanis comes to mind as a refreshing example of an artist that had done just that. But what makes him even more interesting and relevant for us is the fact that he is not just a contemporary painter but also an iconographer of considerable creative potency. There is no question that Kampanis is an iconographer who treats Tradition not so much as a thing of the past, but rather as an ever-renewing living reality, ever present, palpable and accessible today, as it was for the ancient masters. Hence, as the curators of his major retrospective “Painting in Athos 1990-2008” have put it, “…Markos Kampanis is one of the innovators of our ecclesiastical painting; based firmly on the tradition, he doesn’t imitate it but he creates a personal painting style.”[1]

That is, his “innovation,” is not to be confused with “modernist” or anti-traditional subversion, but is rather to be understood as a penetrating and creative interpretation, of the timeless pictorial principles that tie together the best icon painting throughout the centuries. Thus in Kampanis we simultaneously find the rudiments of Modern painting and the iconographic Tradition converging seamlessly. He has thoroughly integrated within himself a whole gamut of 20th century painting techniques and styles: realism, impressionism, post-impressionism, expressionist, “primitivism”, abstraction, pop, etc. At times traces of these pictorial elements might appear organically in his iconography, or conversely, his uncontrived command of iconographic principles might occasionally appear in his non-liturgical work. For him there is no conflict or contradiction, but a complementary dialogue between parallel histories of painting, Byzantine and Modern, that serves to fertilize and fuel his creative oeuvre. In short, for Kampanis the inherent principles of painting (harmony, rhythm, color, value, line and form, etc.) can serve as a bridge across historical and cultural realms.

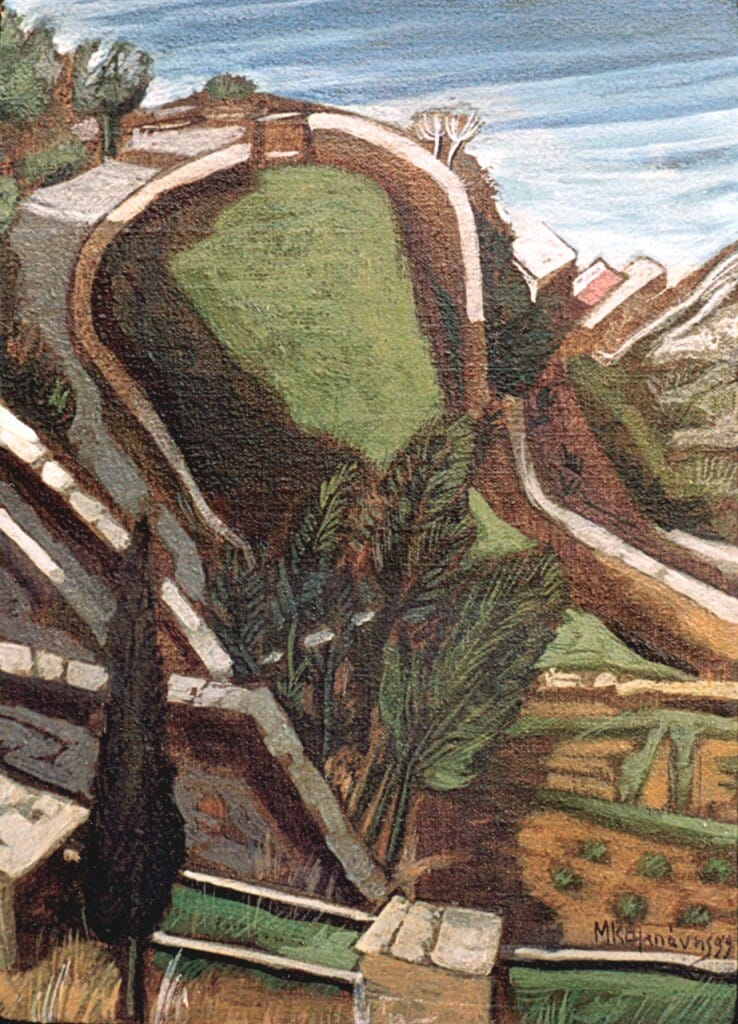

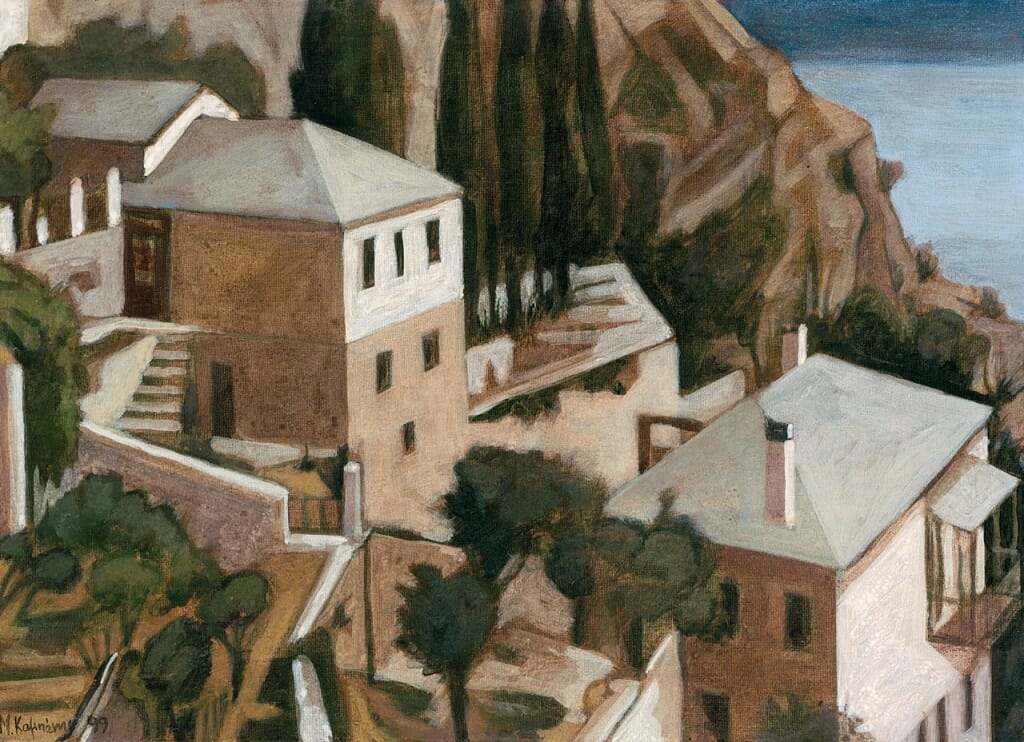

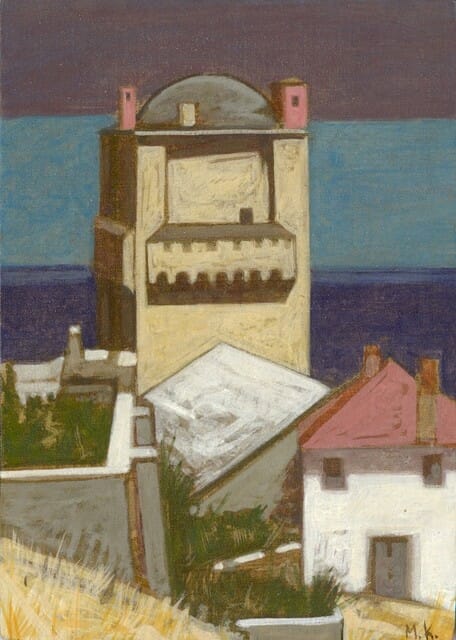

Kampanis was born in Athens in 1955 and studied painting in London where he lived until 1980. He is mainly a painter but also works with printmaking, book illustration and church murals. He has exhibited widely in both one man and group exhibitions in Greece and abroad. In 1984 he participated in the 15th Biennale of Alexandria. The subject matter of his work is broad, encompassing landscape, still life, figuration, and also the exploration of materials and the painting process itself. A major recurring theme of his work has been Mount Athos, which in 2010 became the focus of a major retrospective in the Byzantine Museum, in Athens. Alongside painting Kampanis also engages in art historical academic research, which has led him to book editing and curating exhibitions. He is the curator of The Mount Athos Art Archives, which functions under the auspices of Simonos Petra Monastery and deals with contemporary artistic production related to the Holy Mountain.

So far, as a contributor to OAJ, he has published a couple of articles with us focusing on “The Printmaking Tradition of Mount Athos,” and “Modernity and Tradition in the Religious Art of Spyros Papaloukas”, but we have not yet published anything on his work. What follows is a brief interview with Kampanis as a way of introduction to his eclectic oeuvre, approach to iconography, and his thoughts on the challenges facing an Orthodox artist working between both the secular and ecclesial spheres. As Kampanis suggests, for the painter the tensions and contradictions between these two spheres are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear to be, creative convergences that carve a path independent of the dogmatic demands of contemporary art establishment are possible ̶ “It is a matter of ‘ethos’…”

***

Fr. Silouan: What were the main influences that shaped your formative years while studying in England? Did you find yourself aligned with a particular movement or school of thought during the 70’s and 80’s?

Markos Kampanis: Studying and living in London was a major opportunity apart from my studies at St. Martin’s to visit almost weekly the National Gallery or the British Museum which were both almost next door as well as important exhibitions in commercial galleries by artists such as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach and others. Although my work was never close to some of them I always found it inspiring and satisfying to see their paintings. Perhaps what was closer to my sensibilities at the time was the British version of Pop art as expressed mainly by Peter Blake. A very important formative period was my daily presence for six months at the Art restoration studio that Stavros Mihalarias run in London then. It was there that I came for the first time in real contact with Byzantine icons and also acquired knowledge regarding the use of painting materials. My love for different materials and techniques developed gradually into a form of fetish that I still today try accommodating.

Fr. Silouan: Some would say that liturgical and secular art stem from presuppositions that are ultimately mutually contradictory and irreconcilable. If so, how do you, as an Orthodox Christian, balance these two seemingly conflicting worldviews and understandings of art? How is an Orthodox contemporary artist to understand his vocation without compromising the principles of his Faith?

Markos Kampanis: You have already used some phrases that somehow answer the question: “Some would say…” and “…seemingly conflicting.” I do not follow the argument that the vocation of a contemporary artist may compromise the principles of faith. It is all a matter of “ethos” not a matter of subject, style or technique. Man’s creativity and ability to be expressive through form, color, shape, or through words and music is God given and as such the creative process cannot by definition contradict faith. Nor is it necessary for a Christian artist to be active only in the liturgical realm. There are many painters with a profound Christian faith that have never endeavored to create within the church requirements, and on the other hand, I can think of many church iconographers whose art is such that has nothing to do with the ethos one should normally associate with religious beliefs. I will of course give credit to the assumption that secular and sacred arts may be sometimes contradictory, and such a conflict has become more usual during the last centuries. As we travel back to the past we find that the style of secular artists was very close to religious art, since the aesthetics attributed to specific societies was much more unified and common for all. There was no contradiction let’s say between church mosaics and palace mosaics, between church architecture and secular buildings, etc. as may be often the case today. This widening of the gap between secular and church art in our times may of course be due to the over secularization of modern societies, but we should also investigate the possibility of the Church itself not being able to find a new pace relevant to contemporary changes.

Fr. Silouan: In addition to your liturgical work you have a strong career as a secular painter. In what ways does your secular work inform the creative process of your iconography?

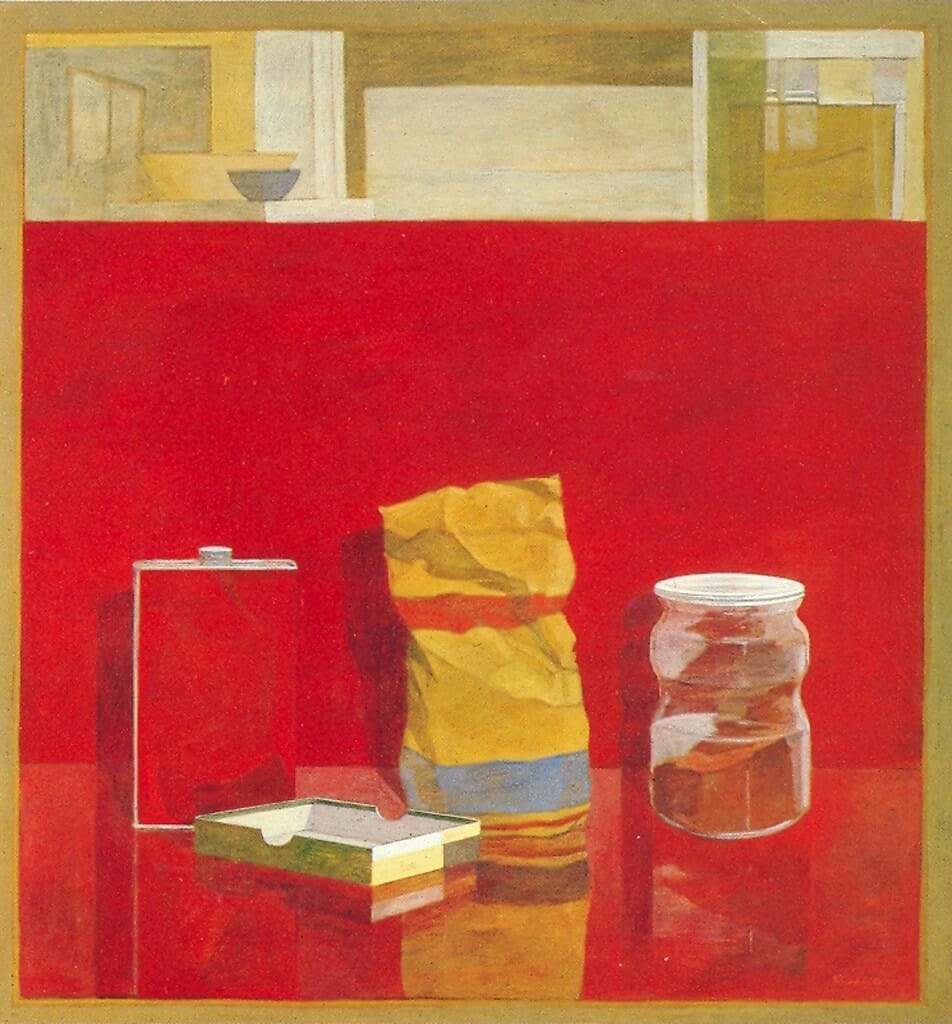

Markos Kampanis: I am trying to bridge such gaps between secular work and liturgical paintings whenever possible without sacrificing the essence or truth of either. I understand that I may not always be successful, but that is a matter for others to judge. I do allow elements of both to cross borders which I do not find to be necessarily strict ones. After all both forms of art are, or should be, based on common principles of harmony, rhythm, coloring or what we often call painterly qualities. I am after all mainly a painter and want to allow the joy of the actual creative act to be present in any case, whether secular or religious. There are paintings which have come about with a distinct influence from my Byzantine-liturgical works and on the other hand religious commissions where the evidence of my painting background is very visible.

Fr. Silouan: How do you see your artistic work in light of the contemporary art scene both in Greece and internationally? Do you consider yourself treading on a path that is mainly considered marginal or left behind by the demands of postmodernism?

Markos Kampanis: I would probably say that I often realize I am rather left behind in a way, or being marginal as you mention, in the sense that broadly speaking I am a representational artist with no eagerness for the necessarily “provocatively new” which is often a demand in the postmodern art market. In most cases I find that nowadays individualism is being mistaken for personality. Another reason that I do not have a strong international market presence may be the fact that I do not like at all repeating myself and so move easily from one style or point of vision to another, which does not provide me with the necessary recognizable style that is sometimes a prerequisite for a successful career. Much of the contemporary art scene is based on conceptualism and the notion that ideas are more important than form or quality, which is not my line of thought, without this implying that I do not find many contemporary artists of a different mentality than mine extremely interesting and satisfying.

Fr. Silouan: Your oeuvre is very eclectic. There is no question that you are pictorially multilingual. At times I sense the echoes of post-impressionism, then expressionism, but there is also abstraction. Sometimes the paintings are very straightforward studies, but then a kind of conceptualism steps in. How do you view this eclecticism and exploration of form? Is it just playful formalism or is there an articulation of specific thematic ideas, a “symbolism”, so to speak, that you want the viewer to grasp?

Markos Kampanis: There is no symbolism in the strict sense of the word. I do agree that you may characterize my work as multilingual. In practice my musical preferences (I always work with music in the background) exemplify in a way this versatility. I move easily from medieval chants to an Asian rhythm or from Italian opera to a Byzantine psalm. Perhaps there is an element of syncretism (comparativism) in my way of thinking. Formalism is not to be understood as a mere play or as a joyful occupation. However, I am a follower of the belief that ideas and concepts spring through the manipulation of form and color. In certain cases there is a strong conceptualism stepping in, but not to the extent that painterly qualities are allowed to be sacrificed. Examples of this are apparent in my two series of works, one called A Museum of Trees and the other 365.

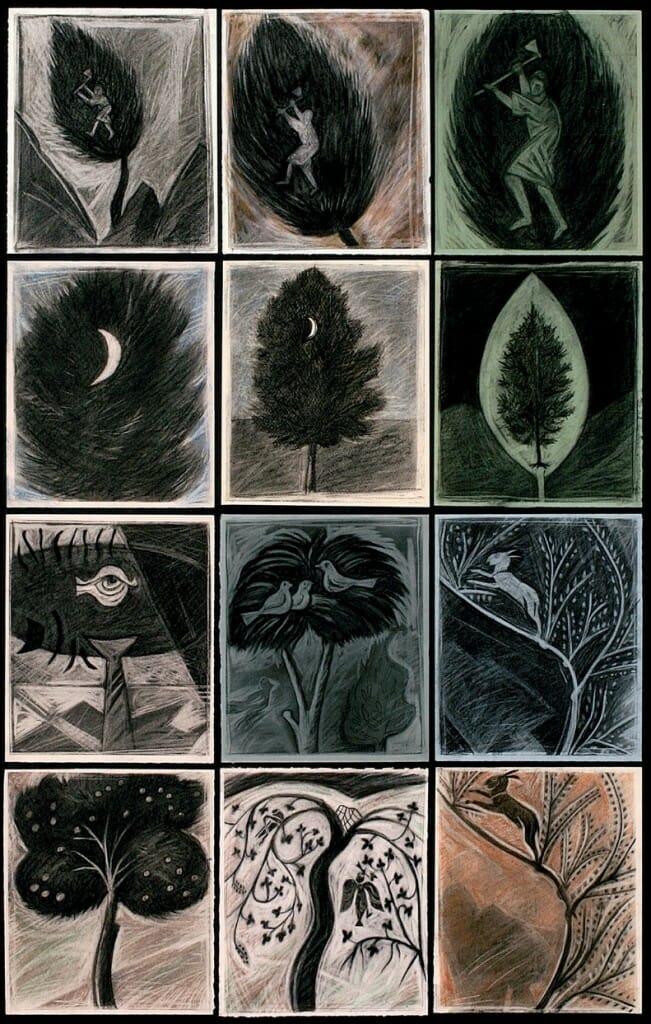

Markos Kampanis, Stories of the Tree, from the series “A Museum of Trees,” 2005. Drawings on paper, 103 x 66 cm.

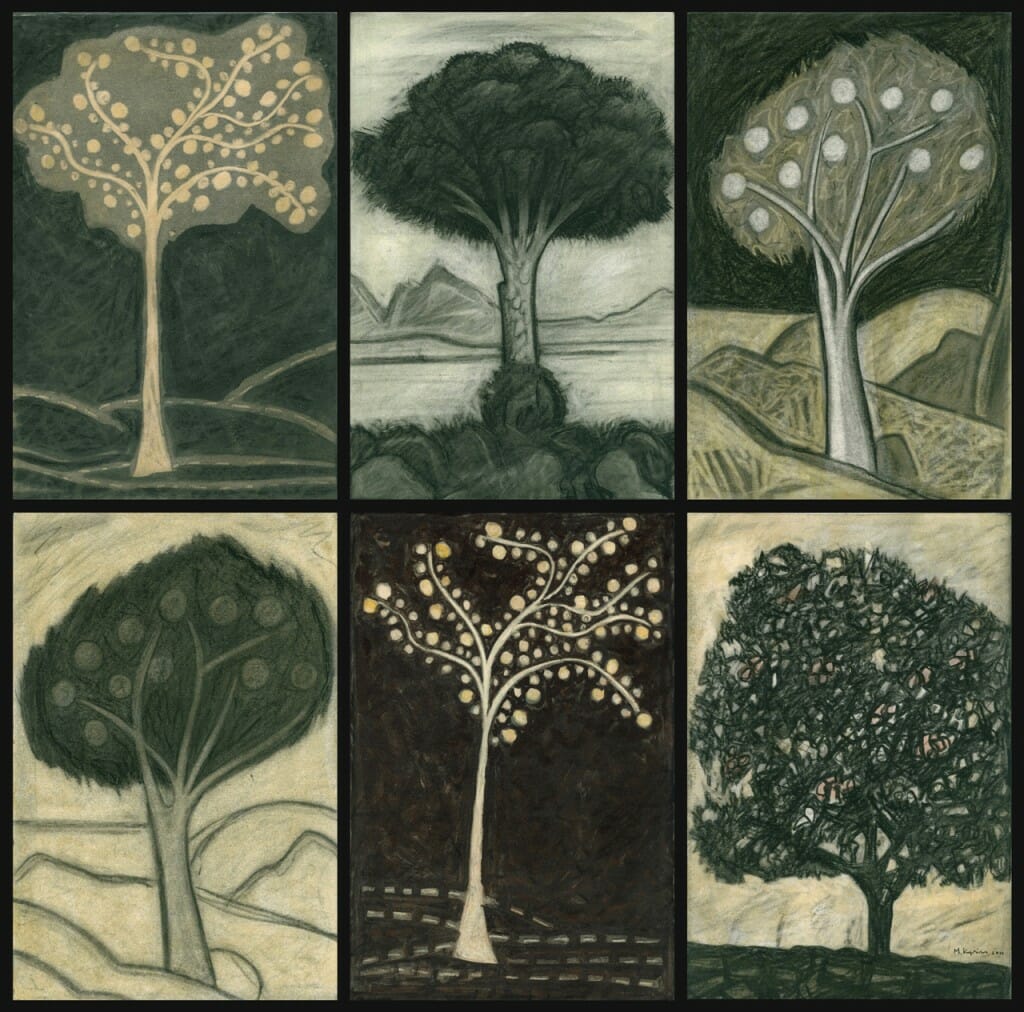

Markos Kampanis, Bridges III, from the series “A Museum of Trees,” 2011. Acrylic and pastel on paper and wood, 66 x 66 cm.

Markos Kampanis, installation of the “365” painting project, Athens Art Gallery, Greece, 2013. For this series Kampanis painted one work every day for a year. As he explains: “From May 2012 to May 2013, I painted one piece each day, to add up to the number of days in the year, 365. The only restrictions were the dimensions and the obligation to paint one piece for every day. There are no restrictions in terms of theme, technique or style. This series is not diary-style record of the events of the year, but more of a personal process of recording moods and choices that emerged during my daily work.

During this journey, I very rarely planned what I would paint the day after and, even during the course of a single day, the choices and desires were so many that they could, in themselves, provide work for months Daily discipline in painting provided the pleasure that drove me to carry on.”

Fr. Silouan: In your most recent article, “Modernity and Tradition in the Religious Art of Spyros Papaloukas,” you state that, “It is important to stress the fact that although today many people and artists easily ground their artistic conservatism behind the teachings of Kontoglou, that was not his intent for most of his career… It was much later in his career, I believe that his teachings were over-systematized. This led many of his followers to a stagnant and uninspiring way of painting icons based on mere copying with lack of artistic personality.” In my opinion, I think your iconography is a good example of a way of painting full of “artistic personality” that is not to be dismissed as crass “individualism”. What would you say helps to avoid stagnant imitation in the creative act?

Markos Kampanis: On the one hand I would say that avoiding a stagnant way of working in icon painting requires in a way the same approach as for any kind of artistic activity: trying not to copy oneself but deal with each work with a fresh and unique manner, trying to solve formal or technical questions arising with regard to personal painterly values, just as one would do with let’s say prayer. It is not enough to merely “read” a payer text; a personal engagement would be beneficial. More particularly, in icon art most iconographers today are over relying on photographs. This was not the case some decades ago, where photographic reproductions where either scarce or not existent at all until the 20th c. Trying to imitate a photograph is not the same as working from an original icon. In older periods icon painters relied only on drawings to produce a new icon or even only on a written description of the saint or feast they wanted to portray. I wonder how many iconographers today can work only from such information. A very important factor as well is the ability and willingness to treat tradition as a spring board, as a starting point and not as a backward gaze. Art education is also extremely important. Many iconographers are taught “how to paint icons” and not how to paint. It is a bit like teaching people “how to paint apples” or “how to paint cats” by following certain painting manuals and believing they would become artists. It is absolutely impossible in my opinion.

Markos Kampanis, Transfiguration, Detail from the mural depicting scenes from the life of Moses, 2007. Monastery of St. Katherine, Mt Sinai.

Markos Kampanis, Portable mural, part of the life of Moses, 2007. Monastery of Katherine, Mt. Sinai.

Markos Kampanis, portable mural, part of the life of Moses, St, Katherine’s Monastery, Mt. Sinai, 2007.

Markos Kampanis, Portable mural, part of the life of Moses, St. Katherine’s Monastery, Mt. Sinai, 2007.

Fr. Silouan: So nowadays, as you suggest, there seems to be two opposing tendencies among iconographers. On the one hand there are the “conservatives,” while on the other hand we have, if we can say so, the “modernists”. The first mainly relegate themselves to the copying of old prototypes, but the second prefer to take risks and, whenever possible, bring into the table the developments of 20th century painting. How do you approach the question of Tradition in your work in light of these two tendencies?

Markos Kampanis: I would not characterize “conservatives” as merely copiers and “modernists” as borrowers of 20th c. painting ideas, or as traditionalists and progressives. It is a matter of a different approach to what we mean and how we treat tradition. At first copies are not by definition sterile and if someone needs a copy then there are ways to produce a decent work. Copiers or not, both have unfortunately produced sometimes very bad work as they are not good enough painters. Tradition is not everything that is past, tradition is not history. Tradition is that part of history that is still valid today. Bringing in as you say developments of 20th c art is not good enough if someone wants to create a contemporary icon. One should strive to find the elements of older iconographic history that are still contemporary, elements that provide answers to contemporary aesthetic problems. Trying to paint today with a full understanding of modern art and thus painting (icons) within this understanding will then produce a modern icon, and not by merely borrowing some element or another and incorporating it in the icon to make it look “modern.” In other words, it is important to try and develop a painting way that is natural, exactly as is a mother tongue and not a foreign language however well taught. Copying from past prototypes and not using them as a starting point only brings forward another problem as well: Why copy the 12th c. or the 14th c. and not the 15th for example? Is it only a matter of taste? But taste or “aesthetics” as such has never been the criterion in tradition. Each century and period of Byzantine art has a distinctive and recognizable style that had to do with theological questions, with social developments, with economic factors etc. So by imitating the Comnenean, let us say, style in the 21st c., even with the utmost accuracy, how traditional can one be?

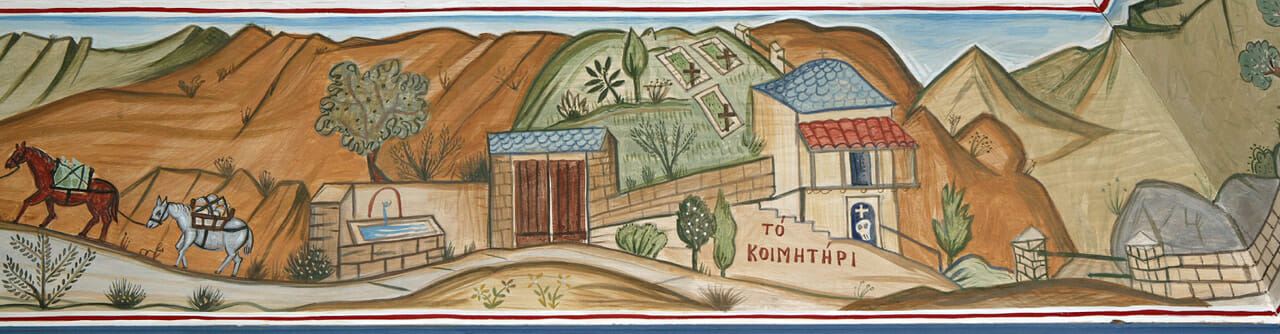

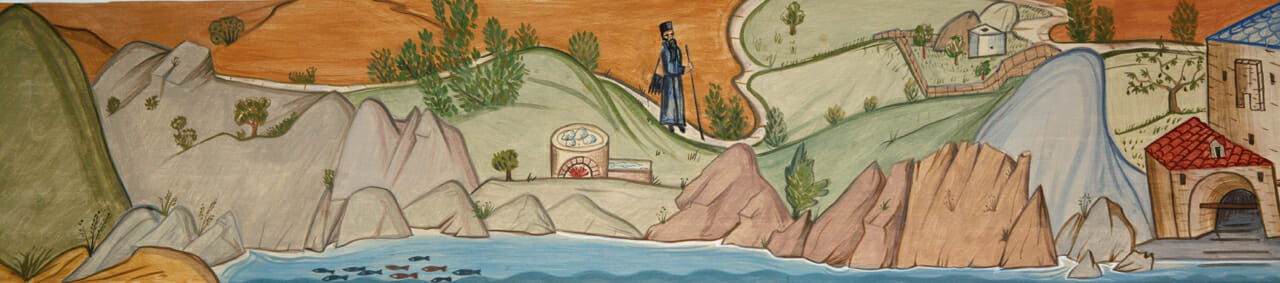

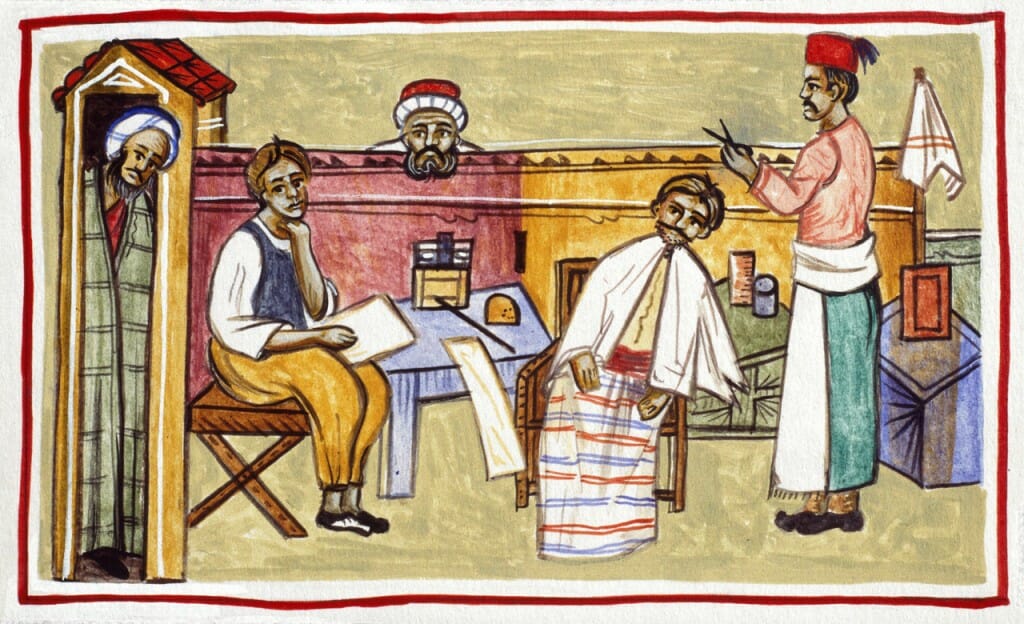

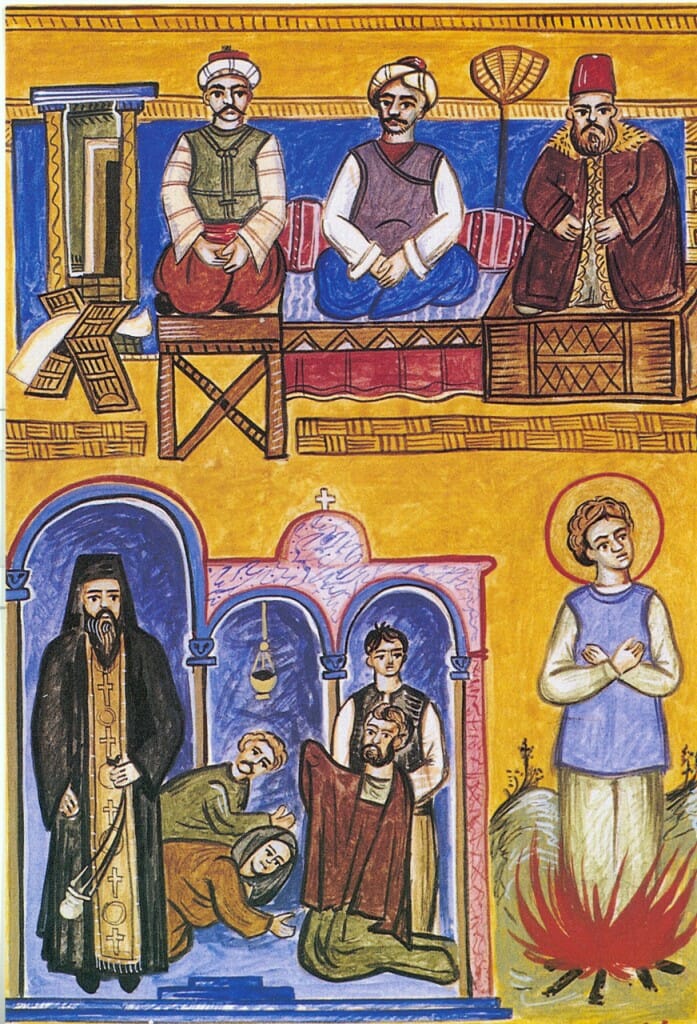

Markos Kampanis, Scene from the story of the icon of the Portaitissa, 2014. Mural at the Convent of the Virgin Mary, Kornofolia, Greece.

Markos Kampanis, Scene from the story of the icon of the Protaitissa, 2014. Mural at the Convent of the Virgin Mary, Kornofolia, Greece.

Markos Kampanis, scene from “The story of the icon of the Portaitissa,” mural at the convent of the Virgin Mary, Kornofolia, Greece, 2014.

Markos Kampanis, Entry to Jerusalem, mural at the convent of the Virgin Mary, Kornofolia, Greece, 2005. Casein and egg emulsion.

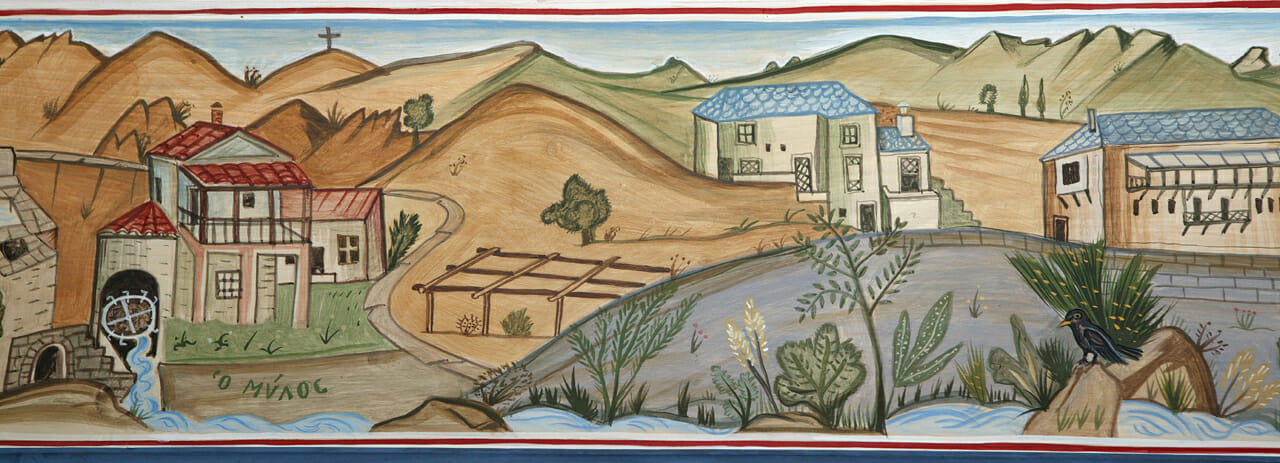

Markos Kampanis, Murals at the Convent of the Virgin Mary, Kornofolia, Greece, 2005. Casein and egg emulsion.

Fr. Silouan: Your church murals exploit the sophisticated language of folk art without appearing contrived. We are not left with the sense that you are just “aping” a naive look from the outside. In other words, there is a true sense of authenticity in this work that can only arise from an honest state of mind, a pictorial “mentality” you have truly made your own. The folk sensibility can also be seen in some of your printmaking and book illustrations. Can you please elaborate on how folk art has played a role on your pictorial vocabulary?

Markos Kampanis: I have been painting in ways which would not be at all characterized as folk or naïf art, but yes I do agree that in my church murals there is a strong thread of what one might call folk art. I do recognize it but it is not intentional, in the sense that this is not my aim from the beginning. I believe this folk sensibility came about gradually and is related to my preferences to periods of Byzantine art that are totally non-naturalistic and a bit “primitive”, like the Cappadocian frescoes, the Coptic murals, early Christian art. Even in European art I do have a strong liking for Romanesque painting and then 20th c art which are both in a way anti-naturalistic. Of course post byzantine Greek folk art and decoration has surely influenced me; I am not however an advocate of a naïf movement, I do not like folk art because it is folk, but admire it for its painterly qualities and its simplicity and straightforwardness.

Markos Kampanis, Murals at the Convent of the Virgin Mary, Kornofolia, 2005. Casein and egg emulsion.

Markos Kampanis, St. Mathew the Evangelist, 2015. Mural at the Convent of the Virgin Mary, Kornofolia, Greece. Casein and egg emulsion.

Fr. Silouan: It goes without saying that your work is unquestionably imaginative. I think this is true not only of your secular work, but also of your liturgical art. However, the common opinion is that icon painting has nothing to do with the imagination, which is mainly seen as detrimental “fantasy.” Would you say that there is a positive role the imagination plays in the creative act of iconography?

Markos Kampanis: It depends what one is imagining about. If by imagination one understands the freedom to make up with purely personal criteria the image of St. Peter or a great Christian feast for example, then yes icon painting has nothing to do with imagination, since any innovation should adhere to the Christian community’s belief and the Church’s teaching. That is, if someone is after creating liturgical art and not art with a religious subject matter. However, if imagination is considered to be linked with the creative process of the act of painting, then there is no contradiction at all. The act of painting whether liturgical or not, is a creative act, and thus imaginative, by definition. After all the church fathers during the Icon restoration stressed the fact that the artistic part, the craft belonged to the artist himself. Even in technical texts about the art of icons, like the “Hermeneia” of Dionysius of Fourna, which is of course post byzantine, there is not even one mention suggesting the style that one should paint in. This was naturally left to the creator’s aesthetics, sensibility, ability; in other words to his creative imagination. Dionysius himself declared that the best master to copy from, the one he admired, was Panselinos and advocated in favor of his style, only that the icons he painted himself have nothing to do whatsoever with the master.

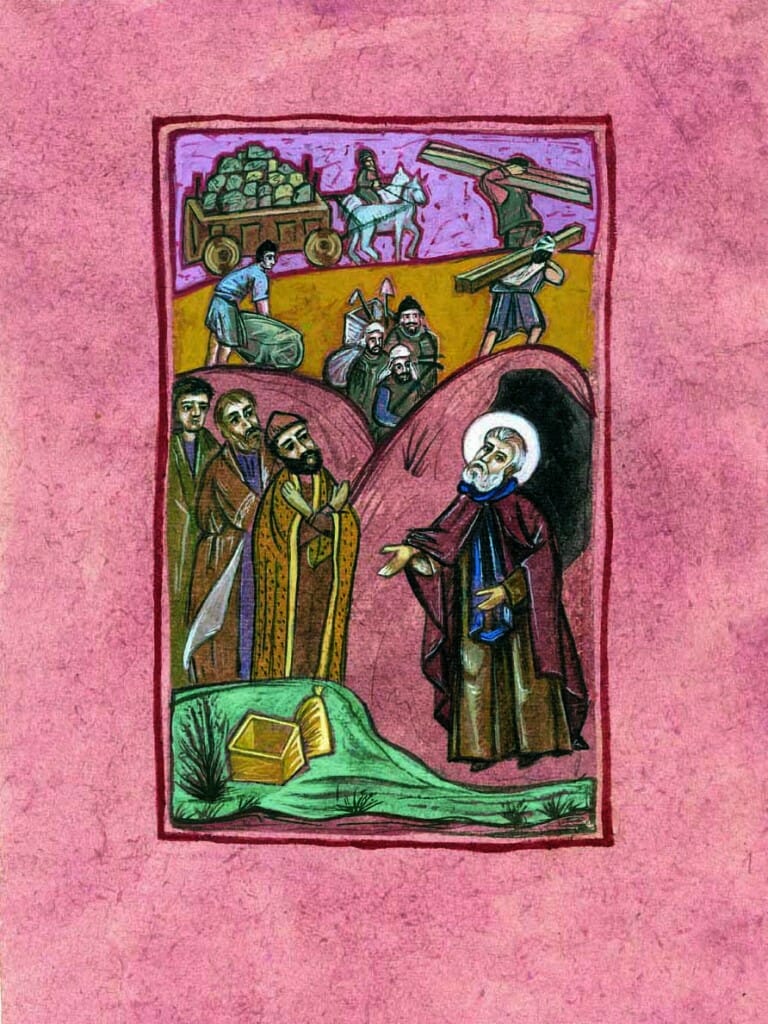

Markos Kampanis, Illustration from “The life of St. Simon the Athonite,” Simonos Petra publishers, 2000. Acrylic on paper.

Fr. Silouan: Much of your work is centered on Mt. Athos, which has resulted in a major retrospective in the Byzantine Museum, in Athens. Can you please tell us how Mt. Athos has impacted your work and what role you play in the Mt. Athos Art Archives, which functions under the auspices of Simonos Petra Monastery?

Markos Kampanis: I first visited Mt. Athos about 25 years ago and have since been there very often, either as a pilgrim or as an artist. Apart from my own work, paintings, drawings, prints, I have mainly worked and executed commissions for Simonos Petra, Iveron and Vatopedi monasteries. The exhibition at the Byzantine Museum in Athens was a very important event in my career. The exhibition included all of my paintings done there, book illustrations, prints as well as reproductions from murals all executed between 1990 and 2008, so it was a kind of Mt. Athos retrospective.

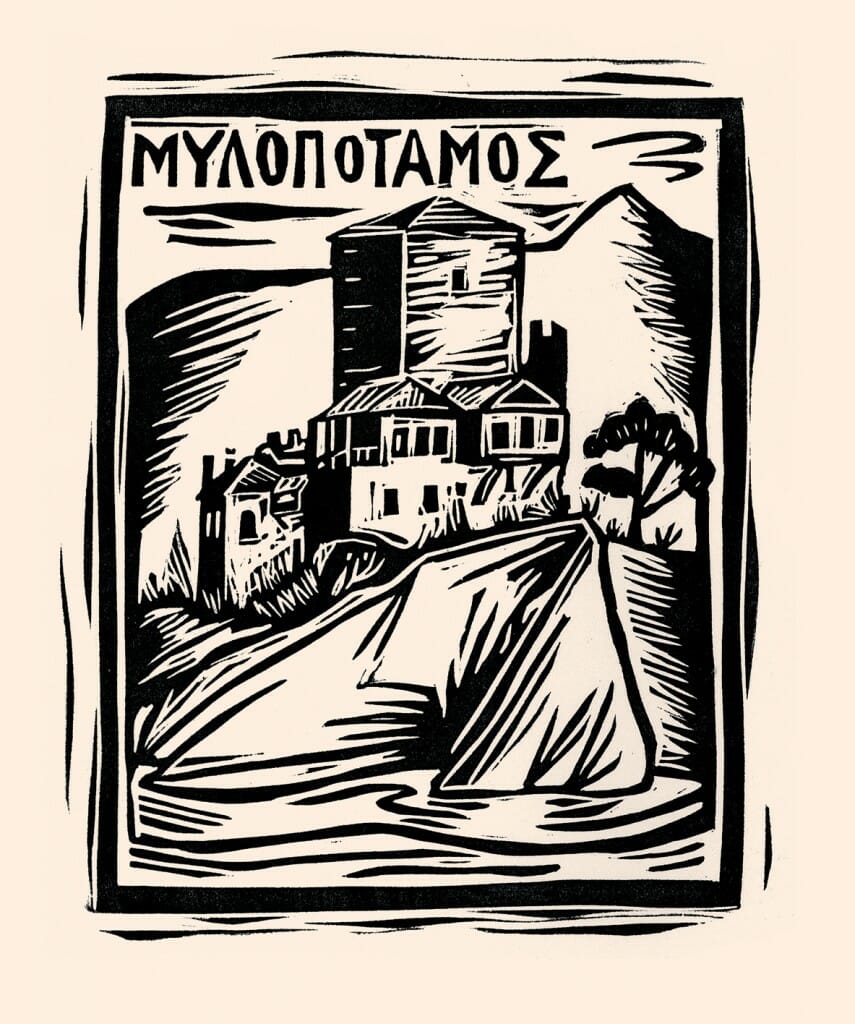

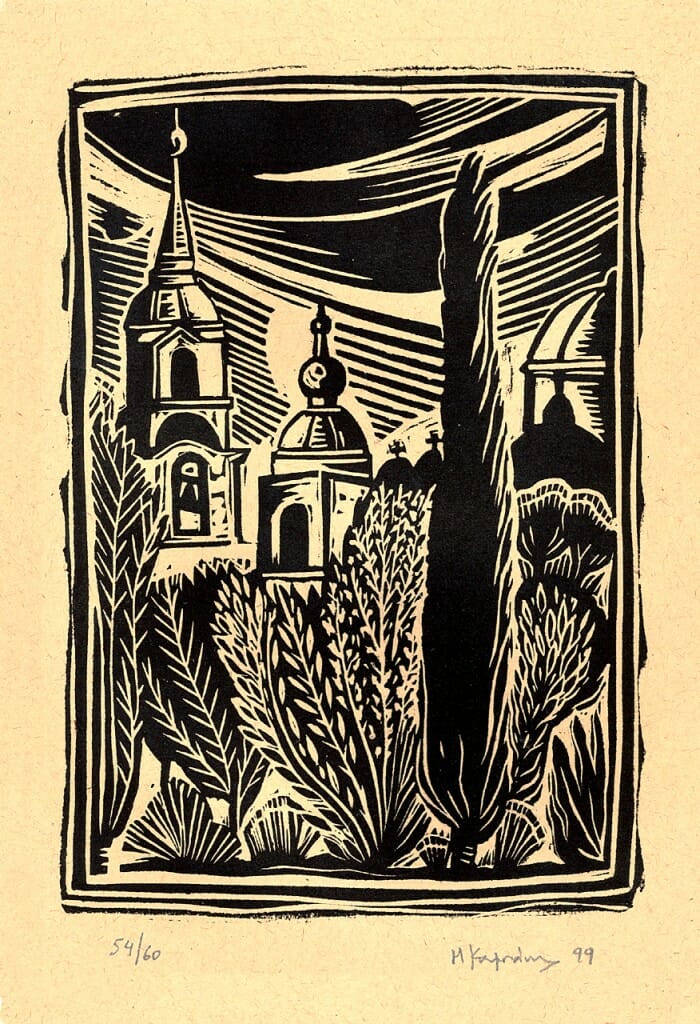

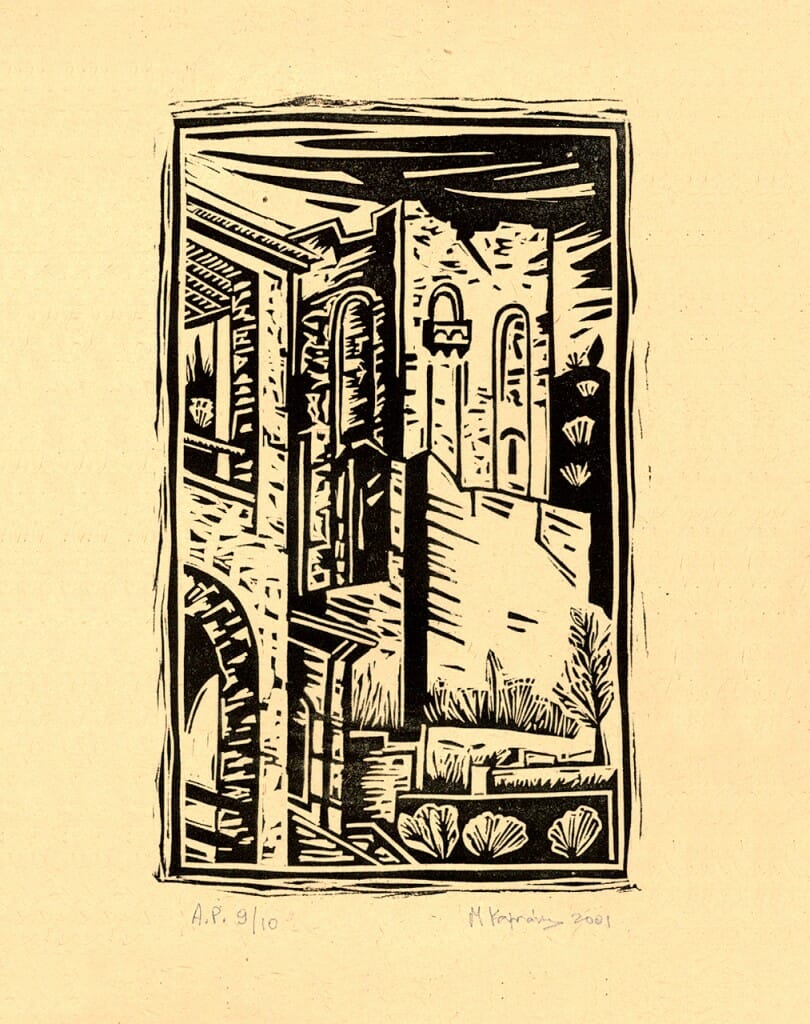

The Mount Athos Art Archives is an organization conceived by the Monastery of Simonos Petra and in particular by Fr. Ioustinos. The Archives do not yet have a physical presence in the form of a gallery; its main interest is studying, publicizing, exhibiting and to a lesser degree collecting art work that is in any way related to Athos. We are trying to make known to the broader public, art forms not usually associated with the monastic society of Athos, but that have nevertheless played an important part in the history of Athonite art during the last two centuries, such as photography and printmaking. As the art curator of the Archives I have set up a printmaking studio in Karyes for the printing of original Athonite copper engravings (see The Printmaking Tradition of Mount Athos), I have edited a book on the Athonite landscapes by the Greek painter Spyros Papaloukas, and curated a major exhibition of paintings regarding 20th c. Greek painting inspired by Mount Athos. The Archives are particularly interested in contemporary art that is related in any way to the Holy Mountain. The Archives have also published a book on the Greek restorer and artist, Fotis Zachariou as well as numerous books and leaflets concerning the history of Athonite photography.

Markos Kampanis, Mylopotamos, from the series “Towers of Mt. Athos,” 1988. Linocut print, 16 x 13 cm.

Fr. Silouan: Did you apprentice under a master iconographer or have you mainly taken an independent course of development as a professional iconographer? What course of study do you think is applicable today for an aspiring iconographer, given that apprenticeship seems to be more and more inaccessible to most?

Markos Kampanis: I have mainly worked independently. My painting studies at art school provided much of what I know together with studying and seeing paintings and icons in museums or churches. This is particularly important for an aspiring artist or iconographer: seeing and studying what others do. I did not apprentice under an iconographer, however I attended the fine art restoration studio of Stavros Mihalarias in London for a few months during 1979 where for the first time I came in real, physical, contact with icons and traditional materials such as egg tempera. Later on I worked with a master of fresco painting in Greece, S. Sergiadis who introduced me to the wonders of mural painting.

As for the ideal course of study, apprenticeship is rather inaccessible today as you said yourself. I believe that a good art course is absolutely necessary, even if focused on teaching a way of perceiving things totally different to Byzantine iconography. Painting knowledge and ability are necessary to any kind of painting. This study should be further enriched by closely studying works of art, icons and murals, from reality, not through books or the internet, on an almost daily basis. Finally, working alongside an accomplished iconographer or muralist should be encouraged, but not taken as an alternative to the initial art studies.

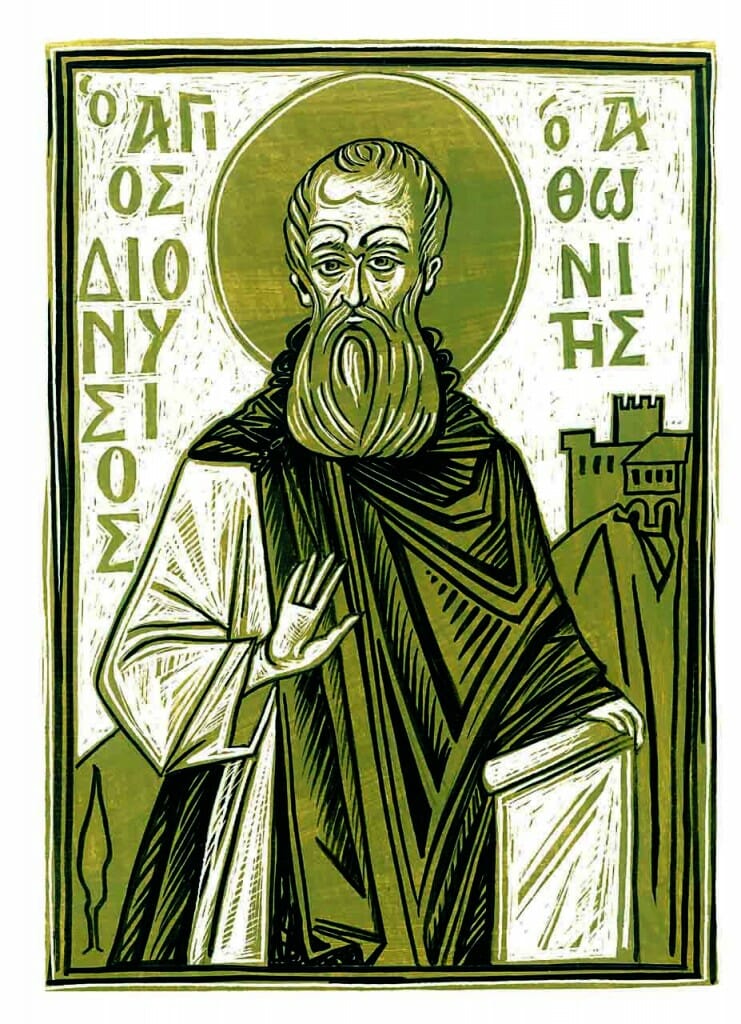

Markos Kampanis, St. Dionysios the Athonite, Illustration from the New Synaxaristis, Indikos publishers, 2006-2008. Two color scratch drawing.

Notes:

[1] See: Byzantine and Christian Museum, “Markos Kampanis, Painting in Mount Athos (1990-2008)”, http://www.byzantinemuseum.gr/en/temporary_exhibitions/older/?nid=1158, 2010 (accessed 8 May 2016).

Wow, what a great interview! I very much enjoy seeing these simple lively paintings, and I especially appreciate that they effortlessly transcend the artificial boundaries we have set up to compartmentalize iconography, decorative murals, and gallery art.

We so often remark that in the middle ages there was no difference in style between iconography and secular painting. But Kampanis seems to have achieved this blessed unity in his own work. One cannot clearly tell whether one of his paintings is liturgical, decorative, or made for an art show. There is little difference in style or subject, and apparently little difference in the artist’s mind. Kampanis is truly what I would call one who lives in the tradition!

Thank you Andrew! I am really glad you like it. It is an honour to have such a nice presentation here. My many thanks and appreciation to all at OAJ.

This man speaks with great authority and I mean both by his words and by his painting, pay attention to them. I would clarify the issue of the distinction between the arts “liturgical,” “religious,” and “secular.” They are useful terms and do have their place but in reality there is a continuum among them. Liturgical art is that which has its place in the liturgy of the church speaking inclusively (including the related decorative arts, architecture etc.). Of course there is religious art that is not liturgical. As a christian painter, my religious and spiritual sensibilities (“ethos”) inform all of my art in some degree whether, at first, it appears to be secular, religious, spiritual or liturgical. DAJ

I do not know if I have succeeded to transcend boundaries between secular and sacred art as Andrew Gould is suggesting. I believe I have not; it would be too much to believe so, although it is natural that such should be the goal of all religious oriented artists, especially practicing Christians. I have been thinking that one reason that unity of the arts was achieved during the Medieval period or in Byzantium and has not been the case during our own times is mainly due to the fact that societies in the past where “unified” in a way, to the fact that art was still a sacred activity and there had been no distinction between secular painting and the religious one. This can be seen when comparing let’s say palace mosaics and church ones, or even during the 15 c, when comparing the iconographic style of Theophanes the Cretan with landscape details seen in parts of his murals, but even much later during the 19thc: at least in Greece there is a very interesting link between folk secular art and Church decoration and iconographic depictions. So we may assume that the secularization of our society is mainly to blame for the gap between secular and liturgical art. But I wonder is this the only reason? What responsibilities do artists have towards this situation? What responsibilities does the church have towards it by trying to cultivate a specific notion of what constitutes tradition, and thus provide the basis for turning liturgical art from a living endeavor to a deadly copying act. The notion of a painterly “mother tongue” is I believe of paramount importance. Most of today’s iconographer’s paint the way they do by either imitating older examples or by interpreting them in a way. In most of the cases they have learned a certain “style” and work with it utilizing, let us say, in a painterly way, a language which is not their own, it is not native, it is a learned dialect which however well taught will still remain a foreign tongue. Part of the reason behind such a situation is the common well spread belief that somehow a so called “byzantine” style is a holy style; a style that by its mere historical usage is alone capable of producing images of “holy” persons or stories. One needs only to compare a Byzantine icon with the Byzantine portrait of Hippocrates or try to find differences between the way a saint’s life and the life of Alexander the Great are depicted during Byzantium : he will find none. These are some initial thoughts on some of the issues and are relevant I believe to the splendid article of Fr Silouan Justiniano, The Threshold, or the latest article by Aidan Hart on the important issue of training for future iconographers.