Similar Posts

“The eye is, to be sure, a small organ in size, but it is more important than all the rest of the body. […] Actually, of course, everything in us is a proof of the wisdom of God, but the eye is so more than any other organ. In truth, it governs the entire body; it adorns the countenance; it is a lamp for all the members. What the sun does in the world, this the eye does in the body. If you should extinguish the sun, you would destroy everything and create chaos; if you should extinguish the light of the eyes, the feet would also be useless, and the hands, and even life. Now, if the eyes have been disabled, wisdom also departs, because by them we know God. […] Surely, then, the eye is the light not merely of the body, but also of the soul more than of the body.”[i]

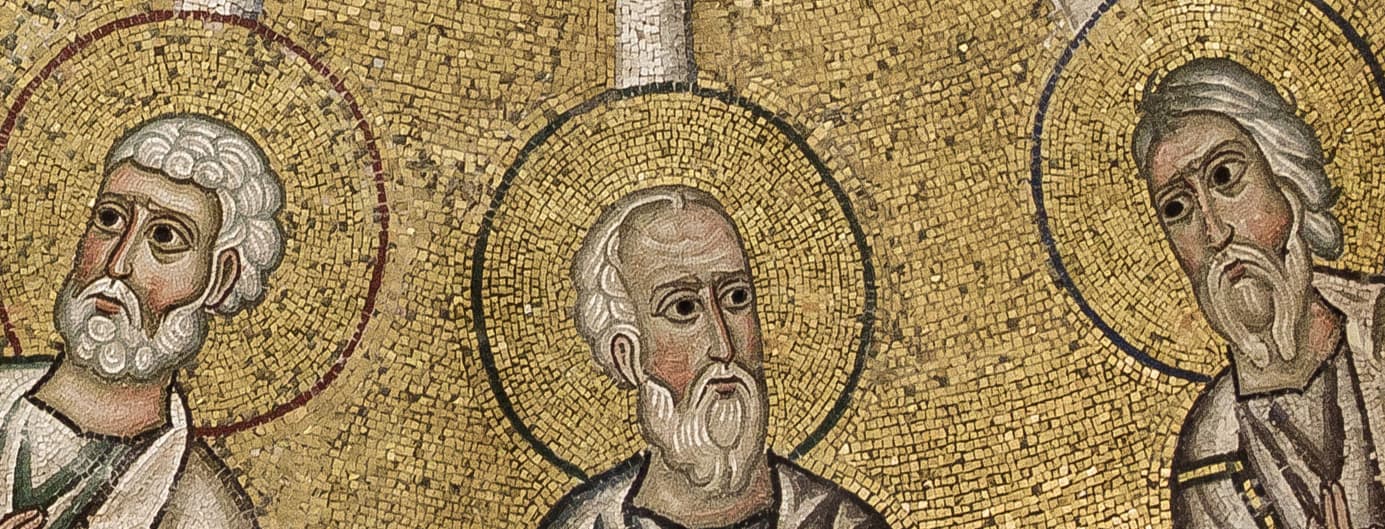

It could be said that this text from Saint John Chrysostom’s 56th homily on the Gospel of John (9:1–5) expresses an astonishing “praise of the eye,” but I would add that this level of praise is in keeping with the contemporary recognition of the highest cognitive importance of the sense of sight. Not unexpectedly, this kind of praise is based in the fact that the “small organ” of the eye is inseparably connected to the notion of light. Together with our daily experience, thus, this quote teaches us that the eye and light cannot be even conceived apart from one another: without light our eyes are useless, while without our eyes light means nothing to us. Furthermore, since we know that the notion of light was essential in almost every aspect of human religious life, then it is not surprising that its receptor was so highly prized in such a context. Consequently, the “small organ” of the eye was very often given special prominence in religious arts. For Christian art, specifically, we can say that it accepted this not merely as a convention, but embraced it most emphatically. Inasmuch as Christian culture was captivated by metaphor, metaphysics and the mysticism of light – which meant uplifting light to the highest cognitive spheres – the eyes in representations of Christ, the Virgin and the saints naturally became the focal points of Christian imagery. To put it simply: the meeting of the eyes of the beholder and the eyes of the saints represented on icons was surely one of the primary goals of authentic Christian art.

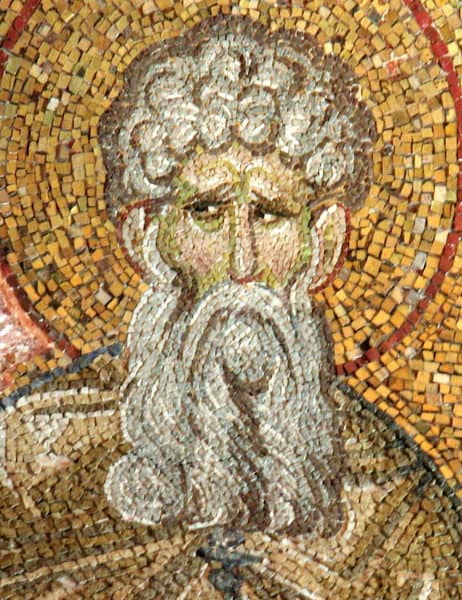

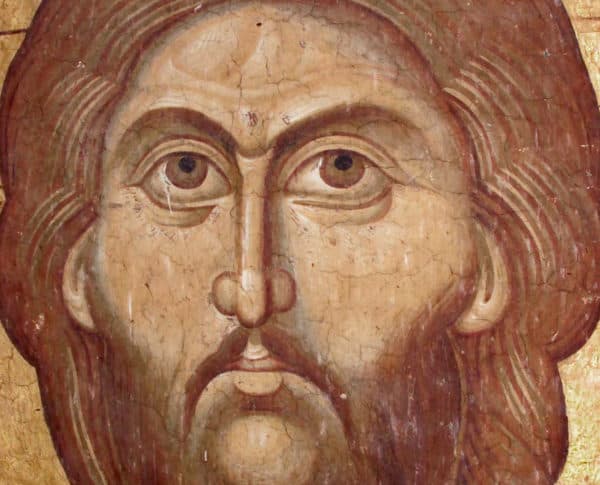

Nevertheless, one simple experience in painting – equally recognizable for a trained artist and for any art enthusiast – raises a set of interesting questions. Namely, the eyes on a painted portrait start “watching” the observer only after their pupils are painted – in black. Of course, these specific brush-stroke(s) need not be literally black, but they must be very, very dark. Especially in medieval icons, the pupil of the eye is the darkest point on the face of the saint and, as it were, totally black – a total absence of light. I am not speaking about some kind of artistic extravagance here. Everyday experience tells us – as to any painter in any culture – that pupils of the eyes are truly black. Nevertheless, specifically in a Byzantine artistic context, this element of the portrait in an icon can raise some intriguing questions.

Inside an ecclesiastical culture obsessed by the notion of light, the art of the icon was surely not an opposition. Not only through the special prominence given to the eyes of saints, but almost every artistic means was used to emphasize light on these images: elimination of shadows, golden background, the use of luminous pigments, the modeling of form with light colors on a darker undercoat… It is difficult to escape the impression that light is a key notion in this specific artistic system.[ii] Reciprocally, darkness had a negative cognitive value. From a painter’s perspective, the correlative of darkness could be nothing other than the color black. Of course, black pigments have been used to make color mixtures of different kinds, or for contour lines in draperies and other objects, but pure black surfaces are rarely seen in Byzantine art. More precisely, almost as though it were a rule, surfaces covered by pure black color represent the symbolically negative parts of icon compositions.

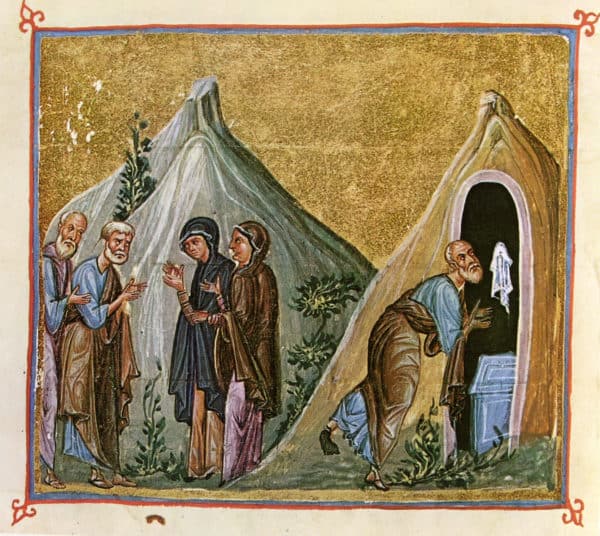

The “figures” of demons or dragons’ caves are the clearest examples of this kind of symbolic logic. Furthermore, the caves appearing in more elaborate theological contexts, in compositions from the cycle of the Great Feasts, are also represented as symbolically “active” spaces of darkness – a kind of metaphysical absence of light. Thus, inside the iconography of the Crucifixion, we can typically find a small cave below the Cross, hiding Adam’s skull in its darkness. During his descent to this same lightless realm, in compositions of the Anastasis, Christ is always raising Adam and Eve above a huge black cave, which represents hell itself. Finally, the darkness of the tomb left behind by the resurrected Christ (or Lazarus) is appropriately shown as black or lightless. From such a perspective, even the cave represented in compositions of the Birth of Christ can be easily understood as a symbol of darkness of the world, where birth in human nature is the first step of kenotic descent of God’s Son towards death. Finally, the caves belonging to scenes from the lives of great monks are not at all like the romantic dwelling places of the hobbits, but rather symbols of the desert, where the most advanced among ascetics have entered the very “frontline” of the war against the demons and the dark forces of human nature. In any of these cases, thus, the representations of dark chthonic spaces are the marks of light-less, being-less and – in the end – the lethal forces of our earthly existence, from which only the light of Christ’s resurrection can save human beings.

It is important to add here that – since we are speaking about ways of artistic expression – there is no need to hypostatize some kind of the ‘ideology’ which would be expected to govern the use of black color in Byzantine art. In accordance with artistic poetics and expressive needs, black occasionally could be used to cover some semantically neutral spaces, such as openings of windows or opened doors, for example. But these exceptions are neither frequent nor systematic enough to be comparable to the systematic and constant use of black in negative symbolic contexts. If, additionally, we consider that the Byzantines inherited from antiquity theories which classified colors on a linear scale – between light/white and dark/black poles – and that they appreciated color hues primarily for their light-bearing qualities,[iii] then we have reason enough to believe that negativity was firmly attached to the darkest among colors in Byzantine visual culture.

This brings us to the focal point of the discussion. Namely, how it happened that the same color was used for the most positive and most negative semantic points inside this artistic system? Or, more precisely, why did the art of icons – understood as theology in colors – accept this dictum from nature? It is well known that Byzantine art was not akin to a literal, slavish, imitation of natural phenomena. Moreover, Byzantine artists were masters of stylization – the painting technique that integrates an arbitrary structuring of the optical information from nature – in an attempt to represent the transformed world, or at least a theologically structured pictorial interpretation of experiences from nature and history. From such a perspective, my question can be posed more precisely: why was this kind of skill not used to make less apparent the relation of the natural color of the pupil of the eye with other spaces of darkness? Furthermore, why have Byzantine artists actually painted in a totally opposite way (as we will see below)?

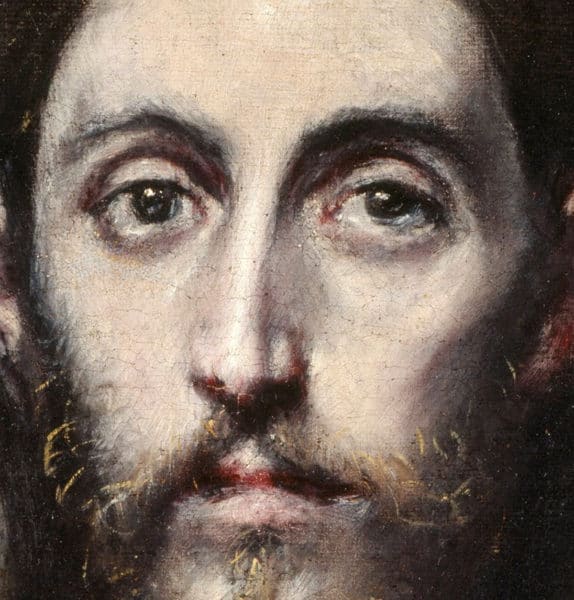

Namely, if this kind of problem existed in their minds, it could have been resolved very simply. Any painter can find this kind of resolution merely by observing nature – as Western painters did during and after the Renaissance: by representing the light that is almost always reflected by the wet surface of the eye. These reflections usually cover the pupil and representing these reflections makes the pupil’s darkness less apparent. In other words, when it is ‘broken up’ by the reflection of light, the darkness of the pupil simply becomes less conspicuous and loses its clear painterly form – the form that could make it symbolically comparable to the other dark components in icons we’ve mentioned. One could say that – in art and in nature as well – the light reflections “protect” the beholder from directly perceiving the deep darkness hidden inside the pupil of the eye. It is as though the light is “masking” the total absence of light that “belongs” to the most important spot(s) on the human face.

Some of the most expressive and profound representations of this phenomenon can be found in the art of El Greco, for example, as one of many signs of his departure from (post)Byzantine artistic conventions. This brings us to the key proposition of the present research: Byzantine painters totally ignored this specific phenomenon, virtually never deciding to represent such a conspicuous optical observation from nature in their art. It cannot be assumed that they did not notice it, since they very meticulously noticed and painted less apparent reflections on other parts of the face – the nose, the forehead, the cheekbones… But, apart from the whiteness of the sclera, light reflections almost never appear in the eyes of portraits belonging to Byzantine visual culture, while the pupils are always invariably apparent, rounded and dark. Moreover, this kind of convention persists throughout almost every developmental phase of Byzantine art. Now icons themselves are posing the initial question of this research: why did something as important as the pupil need to be so dark, in such an intense, resolute and systematic way? Whether on the intuitive or conceptual level, some kind of strict convention obviously existed in this aspect of Byzantine art, so we have every reason to try to explain it – if not its meaning (which might not have been rationally structured), then at least the reasons behind its unambiguous adoption.

While Byzantine intellectuals occasionally debated the ancient – Platonic or Aristotelian, extromissionism or intromissionism – theories of vision,[iv] painters have been obviously focused on carefully observing humans and have recognized that the only absolutely persistent color on the human face is exactly the color of the pupils. And this “color” was actually the absence of color, or – more precisely – the absence of light. The reason for this is well known today: the darkness of the pupil is the entrance to the camera obscura, where light enters but never leaves. In a more poetic manner, one could say that all the light rays that enter this “small organ” are entirely swallowed up and transformed into the images in our minds. In order to become “a lamp for all the members,” the eye must, so to say, capture all the light that enters it. Thus, no matter how we have approached it – whether from an intuitive or a scientific perspective – this organ can be recognized as a kind of cognitive “black hole” which can hardly leave us indifferent, despite – or exactly because of – its persistent darkness. The moment our gaze “enters” the pupil of another human being, this is definitely the most dramatic and the most sophisticated aspect of every human encounter, which opens the doors to intimacy, while – at the same time – reveals one important and insurmountable cognitive restriction. In my opinion, this sort of restriction hides not only the answers to the questions posed, but can become an inspiring interpretative intersection where theology, psychology, physiology and art can meet.

The intimate darkness of our most precious cognitive organ constantly reminds us – whether we like it or not – that the “inner” content of any human is never absolutely available to our cognitive powers. The most powerful among the senses, thus, recognizes the deepest human cognitive powerlessness precisely during the encounter with the most powerful sense organ of another human being. However carefully we approach or analyze it, the unique personal existence of every human always stays partly hidden in the darkness of the unknowing. And this is most expressively manifested when we encounter the small black dot that is the pupil of the eye. At this place we truly do “enter into the human soul,” but at the same time –confusingly and paradoxically – we realize that we cannot enter it. In this kind of darkness, we can get lost and go crazy, or feel warm and safe – for the same reason: because we cannot possess what it reveals/hides. This darkness can be scary or the most welcoming place in the world for the very same reason: because, herein, we recognize the utmost freedom of the human being. Through the encounter with the pupil of another human being, we fall directly into the other’s personal infinity, which can never be fully attained – even if our faces are only a few centimeters from each other. Experiencing this kind of infinity, finally, becomes the cognition of the utmost human freedom – freedom that does not depend even on itself.

Due to this kind of darkness, due to this kind of paradoxical cognitive openness/restriction, every encounter with another is always unique and mystical at the same time. This is why the small dark spot of the eye pupil – in my opinion – becomes the most prominent site for an encounter with mystical apophatic knowledge/experience in our daily lives as Christians. Are we not speaking about something crucially congruent to the apophatic (mystical, negative, paradoxical…) theological motifs such as: “mysterious darkness of unknowing,” the “brilliant darkness of a hidden silence” or the “darkness that is beyond intellect” and “far above light”?[v] Is it not possible to find in the darkness of our eyes the most emphatic icon of the very “intangible and invisible darkness of that Light which is unapproachable because it so far exceeds the “visible light”?[vi] While these images from the Corpus Areopagiticum are the most prominent medieval theological expressions of the ultimate Divine transcendence,[vii] medieval art might be bringing the subject of the ultimate personal freedom of a human being – granted by its iconic relation with the very transcendent One – into this specific cognitive context. The way the mystical Divine darkness protects us from the unbearable brightness of the full knowledge of the Godhead, the mystical darkness of the pupil protects us from the unbearable brightness of the unclouded knowledge of any person who is the icon of the very Godhead. Of course, this kind of ‘protection’ is twofold: no matter how one’s personal (cognitive) powers have been directed, we can recognize the apophatic darkness as a sign of power restriction that keeps one person from possessing the other, or from being possessed by the other person. This kind of power-weakening is what makes the brilliance of the enlightening darkness that connects God and humans – the brilliance of freedom that does not depend even on itself. Thus, the apophatic brilliance of the “ray of the divine shadow which is above everything that is”[viii] – in my opinion – can be experienced every day, only if we are aware of the heights, freedom and infinity which are hidden within any of our friends and neighbors. In short: only if we are aware of God’s iconic presence in any human person.

By taking care that the darkness of the pupil of the eye was always clearly, roundly and conspicuously represented, Byzantine artists clearly recognized that this kind of darkness is something extremely important for our (visual) encounter with Divinity that became human and with humanity that was the true icon of Divinity. The careful removal of the transitory obstacles that could interfere with this encounter is, as it seems, the consequence (and the proof) of this specific recognition. I would say that they have found – probably more intuitively than consciously – the way to represent the very icon of the ‘divine darkness’ inside every single one of their iconic representations. In apophatic theology – so peculiarly prominent in Byzantine light-obsessed culture – the negativity of the darkness was transformed to the mark of the highest knowledge which is “made perfect in weakness.” Thus, the color that was used for the most negative semantic aspects of church art is transformed into the mark of the highest knowledge when it was applied to depict the pupils of the eyes of the saints. The gaze of their widely opened eyes, thus, becomes the true epiphanic center of the icon – from which the entire narration and all of its symbolic and aesthetic layers derive their sense. Or, in negative terms, without the beholder’s encounter with this specific apophatic epiphanic spot, the art of the icon no longer makes sense. Finally, once painters have opened our eyes to the deepest knowledge available to our powerful and powerless sense of sight, then the theology of the icon can start its true life – precisely after our gaze leaves the painted surface. True theology starts at the moment we realize that every day, in every encounter with our friends and neighbors – even with persons we see for the first time – we may be faced with the highest, mystical and epiphanic experience, where infinity is made present and condensed into one spot, while the borders between the Divine archetype and its human icons are erased in most paradoxical and most inexplicable ways.

Notes:

[i] Saint John Chrysostom, Commentary on Saint John the Apostle and Evangelist, Homilies 48-88, transl. Sister Thomas Aquinas Goggin (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2000), 90–91.

[ii] Cf. for example, in: Pavel Florensky, Iconostasis, trans. Donald Sheehan and Olga Andrejev (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1996), 136–159; Liz James, Light and Colour in Byzantine Art (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 91–109; Stamatis Skliris, “Aesthetic Light and Ontological Light in the Art of Painting,” in In the Mirror: A Collection of Iconographic Essays and Illustrations (Alhambra: Western American Diocese of the Serbian Orthodox Church, 2007), 15–32; Slobodan Ćurčić, “Divine Light: Constructing the Immaterial in Byzantine Art and Architecture,” in Architecture of the Sacred, ed. Bonna D. Wescoat, Robert G. Ousterhout (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 307–337; Fabio Barry, “The House of the Rising Sun: Luminosity and Sacrality from Domus to Ecclesia,” in Hierotopy of Light and Fire in the Culture of the Byzantine World, ed. A. M. Lidov (Moscow: Theoria, 2013), 82–104.

[iii] Liz James, “Color and Meaning in Byzantium,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 11, 127.2, (Summer 2003): 223–233; idem, Light and Colour in Byzantine Art, 53–80, 125–127.

[iv] Latest researches on this topic, together with detailed bibliography, can be found in: Roland Betancourt, Sight, Touch, and Imagination in Byzantium (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), especially on pp. 29–50.

[v] Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works, trans. Colm Luibheid and Paul Rorem (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 135–139

[vi] Ibid., 107.

[vii] On apophatic theological traditions and on writings of Pseudo Dionysius Areopagite in this context, cf. for example: George A. Maloney, A Theology of “Uncreated Energies” (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1978), 29–42; Andrew Louth, Denys The Areopagite (New York: Continuum, 2001), 78–129; Paul Rorem, The Dionysian Mystical Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015).

[viii] Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works, 135.

I think you mean the colour of the irides (plural of iris), not the colour of the pupils. The pupil is the aperture in the centre of the iris and is always black, unless the person has a dense cataract. The colour of the iris varies according to the amount of pigment present (blue – little pigment; brown – a lot of pigment).