Similar Posts

Introduction

Blessed is He who has appeared to our human race under so many metaphors![i]

Asked to reflect on the relationship between poetry and theology, I always reach for the above lines of Ephrem the Syrian’s. In some respects, all my thoughts on this matter are circular, starting from and returning to the 31st of Ephrem’s Hymns (or Teaching Songs) on the Faith, of which the above words are the refrain. The core affirmation of the hymn, as of Ephrem’s entire poetic-theological outlook, is this: “He clothed Himself in our language, so that He might clothe us in His mode of life.”[ii] These are tantalizing lines, not only evoking the dynamics of divine incarnation and human deification in a beautiful way, but suggesting the centrality of language to our participation in that process of mutual transfiguration.

A ‘weak’ reading of this claim is that we have been enabled to talk about (and to) God using the multifarious words and images that He himself makes use of in Scripture and Incarnation. A ‘stronger’ reading would be that language itself is infused and leavened with divine presence, liberating our creative and imaginative use of language to make new analogies and metaphors, new images and linguistic artefacts, with the potential to manifest divine reality.

In line with this stronger interpretation, my modest aim in these few pages is to suggest how Ephrem’s example may open possibilities for embracing poetry as a sacred art, and the expression of a broader liturgical disposition, also beyond the immediate context of the church and beyond explicit theological reflection.

Poetry, theology, and the heresy of paraphrase

While it would be unwise to aim to define poetry, certainly for the purposes of this essay, it should be unproblematic to stress that a poem is a linguistic artefact that generates meaning through the indivisibility of form and content, meter and matter, intention and expression. Hence the so-called ‘heresy of paraphrase’, initially articulated by Cleanth Brooks but denoting a widely shared intuition. Paraphrase, while perhaps not necessarily impossible, is inimical to the reading of poetry as poetry: the value of which is largely to be found in the appreciation of the particularities of its form and surface-language, its images and structure, and in the dynamic relations between these, not in the extraction of some abstract or general meaning from that complex integrity.

On a broadly Orthodox understanding of theology, poetic modes of apprehension and expression are germane to theology because of the predominantly apophatic nature of our knowledge of God and, at the same time, because of theology’s primary embodiment or realization in liturgy, hymnody and prayer. Andrew Louth characterizes the formative history of Christian theology as “the efforts by the Church to avoid a series of misunderstandings of a faith expressed primarily in worship and prayer, but easily misconceived in concepts and philosophical categories”.[iii] It is a faith, not least as enshrined within the Orthodox tradition, which lends itself to poetic language, to the use of image, metaphor and paradox. From a poet’s perspective, the most troubling passages in the Gospels are those where his disciples press Jesus to explain the meaning of his parables. We would like to stay with the raw, radiant and often elusive poetic utterance. Religion too often departs from the metaphor and the paradox, settling instead for the paraphrase and making that the basis both of metaphysical speculation and reductive moralization. Thus Christianity, no less than the secular world, falls victim to what David Jones has called ‘utile infiltration’, forgetting the polysemy and the generative possibilities of world and words alike.

The worry about an overly rationalistic approach to theology is nowhere more evident than in Ephrem’s work. While God in his mercy has called us humans gods, Ephrem tells us, we humans in our investigations have delimited God as though he were a man. He asks: “How can the servant, who does not properly know himself, pry into the nature of his Maker?”[iv]

Ephrem’s intuition that certain modes of language and thought may fundamentally misapprehend and misrepresent reality, reducing it by objectifying and circumscribing it, is presciently suggestive of some key contemporary debates. Thus Malcolm Guite rightly cautions against the creeping scientism within the humanities; specifically, when it comes to theology, the over-reliance on “a logical and syllogistic method”, the abstract language of which “pretends to a precision, a finality that it cannot deliver” and which therefore is “potentially more idolatrous than the images of which it is suspicious”.[v]

Kees den Biesen, in his outstanding study of Ephrem’s symbolic thought, affirms this and notes the value of the alternative approach exemplified by Ephrem. “With respect to contemporary Christian thought,” den Biesen argues, “Ephrem’s particular importance and topical interest lie in the fact that he shows how a symbolical discourse honours the mystery of reality much more than a rational discourse, which runs the risk of idolizing the conceptual and annihilating the mystery for the sake of a rationalistic form of intellectual clarity.”[vi]

The paradoxical relations between the hidden and the revealed, and between the uncreated and the created, are the heart of Christian theology and the key themes of the best theological poetry from Ephrem’s time to our own. “It is in fact only the paradox that can begin to describe the indescribable,” writes Sebastian Brock, suggesting that “St. Ephrem could very aptly be called ‘the poet of the Christian paradox’”.[vii] The same point is developed by den Biesen, arguing that “polar or antithetical structures are the only appropriate means to express the symbolical nature of reality, that is, the mystery of God as it presents itself through the mediation of all creation”.[viii]

Similar convictions surely underpin the playful use of language in the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Here is the second stanza of “Pied Beauty”:

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.[ix]

Just as, in a metaphor, two things meet to mutually engender something yet more and other, so, for Hopkins, couplings of contraries become signs of God’s abundant and boundary-breaking glory. We see also how the poem joyfully adopts an apophatic stance in celebrating the wonder and gratuity of that which surpasses human comprehension.

The resonances with the Syriac and Byzantine Fathers are many. Here are some lines from Ephrem’s first Hymn on the Resurrection:

Whom have we Lord, like You –

The Great One who became small, the Wakeful who slept,

The Pure One who was baptised, the Living One who died,

The King who abased himself to ensure honour for all!

Blessed is Your honour![x]

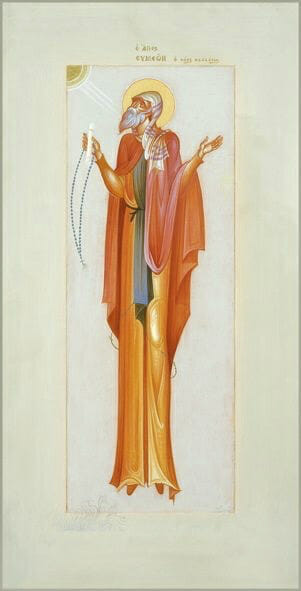

“In theology, as in poetry, the boundaries of language expand,”[xi] C.A. Tsakiridou writes; especially so, she argues, in the existential and dynamic theology of the Orthodox world. Commenting on Symeon the New Theologian’s encounters with the divine light, Tsakiridou observes: “Pairs like visible invisibility, formless form, immeasurable measure etc. are everywhere in [his] verse. They are not only rhetorical tropes. They are also the liminal forms of a reality that language cannot contain”.[xii]

Against the alienating and restricting language of definitions, then, we have the relational language of praise and address, as well as the language of image and metaphor; and this is as should be, seeing as we are image-making beings made in the image of God, creative beings called to union with the uncreated. This use of language can be understood as liturgical, both in the sense of initiation into a mystical and symbolic reality, and in the sense of us creatively and prayerfully making an offering to God of what he has originally given us. Freed from its utile trappings, language is liberated to make a gift of itself and of the world. At its best, in its liturgical and poetic modes, religion is rescued from explication and restored to experience of the divine.

In these remarkable lines, from his Hymns on Virginity, Ephrem characteristically draws on a Gospel episode to both evoke the symbolic fabric of the world we inhabit and suggest our liturgical participation in it:

In the alabaster vase that she poured over Him,

she emptied out over Him a treasury of types:

At that moment the symbols of oil found their home in Christ,

and oil, that treasurer of symbols, handed over the symbols to

the Lord of Symbols.[xiii]

Poetic contemplation of nature and language

The object of theology is not simply God in himself, but also the theological fabric of existence, the created as participating in the uncreated, God as manifested in the world. We are here in the realm of what is often called natural contemplation of the divine. Drawing on strands of theology from Gregory Palamas and Maximos the Confessor, Louth writes that “the whole created order is to be seen as a theophany, a manifestation of God, indeed a manifestation of God’s beauty.”[xiv]

We know that poetry is exceptionally equipped to kindle our appreciation of the beauties of nature. But, what is more, in the very act of doing so, it also makes us attend to the glories of language itself. I, for one, in reading Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty”, delight as much in the play of the language as in the vision of the world it gives; and it is in this language, no less than in the phenomena there re-presented, that I may apprehend the sacred fabric of beauty and form, of paradoxical relations and irreducible particularities. Here is the first stanza:

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.[xv]

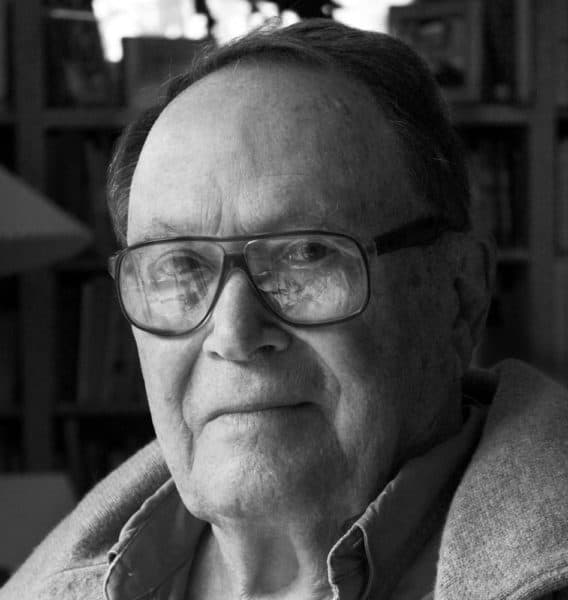

On one level, then, poetry can proclaim or point to the divinely energized fabric of creation. On another level, however, we encounter also its ability to make these divine energies palpable in aesthetic experience and creative practice. For a more contemporary example of how such a liturgical disposition can be played out in response to the beauty and gratuity of the natural world, let us turn to Richard Wilbur’s “Hamlen Brook”. Crucially, this is also a poem without apparent religious or theological preoccupations. The poem begins:

At the alder-darkened brink

Where the stream slows to a lucid jet

I lean to the water, dinting its top with sweat,

And see, before I can drink,

A startled inchling trout

Of spotted near-transparency,

Trawling a shadow solider than he.

Following this, the long sentence at the heart of the poem, strung out over four stanzas, is quite difficult to read: we experience the syntax struggling to keep up with the flowing phenomena, as a multi-layered vision of reality teasingly tugs both sense perception and language to the very cusp of their capacities for registering and representing the world. In the way the rhythm ripples over the supple iambic beats, and in the undulations of tri-, tetra- and pentameter lines, the poem achieves movement and variation as well as regularity, the enjambment of lines and stanzas more than mimicking the brimming and meandering brook. The sentence ends, significantly, with the world turned on its head, fully immersed in the water and transfigured in the process, as

birch-trees plunges down

Toward where the azures of the zenith drown.

After that long, breathless sentence, the verse is halted in wonder:

How shall I drink all this?

Joy’s trick is to supply

Dry lips with what can cool and slake,

Leaving them dumbstruck also with an ache

Nothing can satisfy.[xvi]

The speaker comes to drink, and gets more than he knowingly thirsted for. For those of us interested in the links between poetry and theology, the poem is irresistibly suggestive. The imagery is by turns baptismal and Eucharistic. The final line, meanwhile, is an apophatic masterstroke, allowing us to read ‘Nothing’ as ‘only God’ or, at least, as ‘no finite thing’.

The poem, like much of Wilbur’s work, affirms the goodness of creation itself and the meaningfulness of our imaginative being in the world. Wilbur has said that “the world is fundamentally a great wonder and a great order”.[xvii] “Hamlen Brook” is emblematic of such a view, and iconic of such a world. Crucially, the poem instantiates the order and wonder it celebrates. The poem does for us what the brook does for the speaker. It offers us enchantment and joy, relief and replenishment, but kindles in us also a thirst for more of that elusive plenitude which the poem partakes of but does not entirely possess, which we may drink of but not exhaust. There appears to be no distinction between nature and grace in Wilbur’s poetry: the natural, when seen aright, taken up in a poetic mode, is shown to be already graced. The suggestion is that world and language are not themselves fallen, but our perceptions and practices are; that language wielded rightly can cut through occlusion and alienation to restore a fresh apprehension of the world as it is (and as it is ever made new precisely by our creative engagement).

Implications and concluding thoughts

“A poem must not be about an event,” says the contemporary Orthodox poet Scott Cairns; “it must occasion an event of its own”.[xviii]

It is in seeing poems like “Hamlen Brook” as events and things in their own right that we may also discern their theological and theophanic potentials. This is key to an understanding of ‘sacred’ art or poetry in general: our creative works may be considered sacred, not simply for what they say, but for how they say it: indeed for what they are as instantiations of a transfigured world.

A point so obvious that it is often overlooked must be made: a poem like “Hamlen Brook” is an artefact, not an argument. We are dealing with a work of art. Thus, even though the poem may be seen to make a point, even an old and unoriginal point perhaps, the crucial thing is that a new thing is being made. A poem like this brings something new into the world, and in so doing renews the world as we know it.

In another notable poem by Wilbur, “Lying”, the speaker strikingly remarks how it is “odd that a thing is most itself when likened”[xix], suggesting that it takes metaphor and other poetic means to adequately re-present reality, and for reality to come to full articulation. We may learn from Wilbur, then, as from William Blake and other poets and artists, that to an insatiable imaginative engagement with the world, the world is truly inexhaustible. We can also learn something of how human creativity is implicated in the unfolding of such a reality.

Great works like these impress on us the need to consider how a thing made in a particular way can manifest the divine; and how our thing-making can manifest the divine in us. As also contemporary Christian artist-theologians like Davor Džalto and Makoto Fujimura may affirm, we are never more in the divine likeness than when freely making in and out of love. We come away from great art and poetry with a sense of human creativity as synergetic with the divine: as not only utilizing resources or potentials of the created world, but indeed drawing from a wellspring of divine creativity itself.

Poetry does not serve religion; poetry, at its best, serves a reality that religion, at its best, also serves. The poet or artist, in order to stay true to his or her creative vocation, no less than to a religious tradition, cannot but hold that creativity is a mode of continual revelation; not just commenting on antecedent doctrines or discoveries, but articulating an ever-unfolding reality. So that, in effect, we can know God and the world better after experiencing the poetry of Ephrem, Hopkins, Cairns or Wilbur, than we did before.

Poetry is thanks-giving, written in gratitude for a graced reality, but it is also itself grace-giving. And so, in joining again with Ephrem, we give thanks, not only for the gratuities of the created world, but for the gifts and possibilities of poetry itself:

Blessed is He who has appeared to our human race under so many metaphors!

Notes:

[i] S. Brock, The Harp of the Spirit: Poems of Saint Ephrem the Syrian. (Cambridge: Aquila Books,

2013), p.85.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] A. Louth, Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology (London: SPCK, 2013), p.22.

[iv] Ibid, p.8.

[v] M. Guite, Faith, Hope and Poetry: Theology and the Poetic Imagination. (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), p.11.

[vi] K. den Biesen, Simple and Bold: Ephrem’s Art of Symbolic Thought. (New Jersey: Gorgias Press,2006), p.322.

[vii] Brock, The Harp of the Spirit, p.17.

[viii] den Biesen, Simple and Bold, p.84.

[ix] G.M. Hopkins, Selected Poems. (London: Heinemann, 1961), p.24.

[x] Brock, The Harp of the Spirit, p.40.

[xi] C.A. Tsakiridou, Icons in Time, Persons in Eternity: Orthodox Thelogy and the Aesthetics of the Christian Image. (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), p.27.

[xii] Ibid, pp.252-3.

[xiii] Brock, The Harp of the Spirit, p.16.

[xiv] Louth, Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology, p.66.

[xv] Hopkins, Selected Poems, p.24.

[xvi] R. Wilbur, Collected Poems 1943-2004. (London: The Waywiser Press, 2005), p.137

[xvii] https://www.kwls.org/key-wests-life-of-letters/the_world_is_fundamentally_a_g/ [accessed Febraury 27, 2022]

[xviii] https://www.patheos.com/blogs/lookingcloser/the-event-of-poetry-a-conversation-with-poet-scott-cairns-about-reading-writing-and-responsibility/ [accessed February 27, 2022]

[xix] Wilbur, Collected Poems, p.106

Daniel Gustafsson is a poet and scholar originally from Sweden who now lives in York. He received a PhD in Philosophy from the University of York in 2015. Daniel’s PhD thesis, A Philosophy of Christian Art, offers an original approach to the understanding of Christian art.

Daniel’s poetry is represented in numerous journals and anthologies, including Black Bough Poetry’s Deep Time: Volume 1 (July, 2020). New poems appear in The North American Anglican, The Brazen Head, Trinity House Review, The York Journal, Ekstasis, Fare Forward, and Amethyst Review. His first Swedish-language collection, Karve, was named one of the best books of 2016 by Peter Nyberg, editor-in-chief of the magazine Populär Poesi.

Daniel’s scholarly work engages with philosophy, theology and the arts. He is particularly interested in William Blake, Roger Scruton, David Jones and the Eastern Orthodox tradition. He has written chapters for the following books: David Jones: Christian Modernist? (Brill, 2017); Looking at the Sun: New Writings in Modern Personalism (Vernon Press, 2017); Love and its objects (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); Religion and Art: Rethinking Aesthetic and Auratic Experiences in ‘Post-Secular’ Times (MDPI, 2019). Daniel is also a contributor to several journals, among them Religions, Religion and Literature, Religious Studies, Sobornost, Appraisal and the Russia-based journal Language. Philology. Culture.

For more information on the work of Daniel Gustafsson visit his website.

[…] March 22nd: New article, reflecting on poetry as theology, for the Orthodox Arts Journal: https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/poetry-as-theology-reflections-on-ephrem-the-syrian-and-richard-wilb… […]

I’ll add that many of our troparia and kondakia, composed by St. Roman the Melodist, reflect the Syriac tradition of writing theology as poetry.

My father knew Richard Wilbur. He said the most striking thing about him other than his intellect was his wonderful voice.

A wonderful article. Thanks for this.

[…] ИЗВОР: https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/poetry-as-theology-reflections-on-ephrem-the-syrian-and-richard-wilb… […]