Similar Posts

Dr. Davor Džalto is professor of Religion, Art and Democracy at Saint Ignatios College in Sweden. His research focuses primarily on the exploration of human freedom and creativity, as metaphysical, political, as well as aesthetic concepts. All of these concerns come together in his book, The Human Work of Art: A Theological Appraisal of Creativity and the Death of the Artist, which engages aspects of conceptual art through the lens of Orthodox theology. Among the artists interpreted in this appraisal we find Marcel Duchamp, Yves Klein and Andy Warhol. Also discussed are the commonly held assumptions regarding the modern paradigm of Fine Art, including its social and ideological function. Going beyond these assumptions, Džalto shows how creativity is not to be limited to the manufacturing of objects or art as a commodity product but rather bears anthropological significance, touching on soteriological, eschatological and ecclesial dimensions.

To some, Džalto’s work might seem unrelated to the general focus and aesthetic orientation of OAJ. In my view, however, it is quite pertinent although challenging, suggesting ways in which we can expand the discourse concerning the question of “Art” from an Orthodox theological perspective, beyond the limited perimeters of liturgical art. In the Orthodox anglophone world studies focusing on the topic of contemporary art and its theological significance are almost nonexistent. Džalto’s work thus offers a very important contribution, helping to close the gap between the seemingly unrelated fields of theology and contemporary art. As I’ve mentioned previously, not every artistically inclined Orthodox Christian will necessarily have a vocation as a liturgical artist. Some will choose to navigate the challenges of contemporary art. This fact raises many questions that cannot be dismissed as irrelevant. The answers are not to be found in an insular approach, in disdainful retreat and disregard for the sphere of non-liturgical art. The Sacred is to be found in places where we least expect it. With these issues in mind, what follows is an interview I had the pleasure to conduct with Dr. Davor Džalto, in which we explore some aspects of his work and art theory.

***

Fr. Silouan: Prior to embarking on your academic career at the University of Belgrade you actually attended the School of Art in Niš. Tell us about your early years in art school and how you gradually became more actively involved in the contemporary art world. What precipitated your interest in art in the first place?

Davor Džalto: First of all, thanks for your kind invitation to speak for the Orthodox Arts Journal. I’ve always been interested in art, and have been drawing and painting since I can remember. I’ve also been interested in all sorts of other things, primarily literature and philosophy. I was lucky to have an extraordinary art teacher in primary school – Branko Nikolov – one of the greatest printmaking artists I’ve ever met. He supported me in my intention to try to enroll into the School of Art, giving me additional classes, providing also the necessary materials, such as charcoal, paper, brushes… At that time, it was very difficult to pass the entrance exam, and the competition was very strong. During the preparations for the entrance exam, and then, through my work within the School, I discovered those very tactile, aesthetic dimensions of an artistic process – when you smell tempera or oil paint, turpentine, when you discover how pleasurable it is to use different textures, what a joy it is when you draw and paint for many hours, forgetting to eat and sleep.

I very much enjoyed the fact that many – if not most – of the School’s teachers and students were genuinely interested and passionate about art. We used to spend many hours, apart from official classes, working on our projects, discussing ideas, reading about different periods from art history and about the artists we liked. At that time, I also started participating in many artists–in–residence programs, which helped me meet many interesting people, explore the boundaries of my own artistic interests, and make friends among fellow students and teachers of art and literature. In many ways, those years were formative and defining for my future work. In addition to lectures, discussions, studio work and events in public spaces, partying properly was an indispensable aspect of life/work – and ever since I’ve been convinced that partying is an indispensable part of any serious academic endeavor.

During those years, I started exploring alternative media as well; apart from painting, drawing and printmaking, I started doing performances, installations and interventions in space, I became familiar with Conceptual Art and read art history, philosophy and religion books. I also started experimenting with haiku poetry, and even published a couple of poems in haiku poetry journals. I still have about a hundred poems from that time. My first book, on calligraphy and typography, was also published back then. I took a course in traditional icon painting, and got interested in the work of Nikolai Berdyaev. I have a feeling that everything I’ve been doing ever since, everything that is really important to me – above all, the love of love, freedom and creativity – has its roots in those years, during my stay in Niš, where I ended up more or less by chance, as a refugee, escaping the ongoing war in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

FS: It could be said that, from the very beginning, you have followed parallel paths as both a scholar and contemporary artist. How has your Orthodox faith shaped your approach to artistic practice? And how has your artistic practice in turn impacted your scholarship?

DD: As I said, I was lucky to realize, at an early stage, that freedom and creativity, together with personal relationships with other people (that can be even more creative and liberating than particular practices, such as painting or writing) – is “my cup of tea.” Parallel to my interest in artistic practice and art theory, I was discovering philosophical and religious ideas and practices. In the work of Nikolai Berdyaev, I found a way of relating all of these things, of sensing something “greater than life” as it were. Berdyaev also helped me bridge the gap between “theory” and “practice,” which I found very problematic. I realized that in everything I was attracted to, in everything I was doing, I was actually interested in the same issues – freedom, creativity, and love. That is how I found a way to relate activities that may appear as very different. I have remained a “captive of freedom” ever since.

FS: When you speak of freedom, of course, we should not confuse the term with the exercise of egocentric and irresponsible license. Am I understanding you correctly?

DD: Yes. “Freedom” is normally understood nowadays as a possibility to satisfy our egocentric drives to do “whatever we want” or to be “whoever we want to be.” However, it is actually a special kind of slavery. What appears to us as “freedom” is, in actual reality, a very codified system of desires and wants that are shaped by social/ideological imperatives (imposed by, for instance, the corporate sector). Our “spontaneous” desires to be this or that, to do this or that, are rarely authentic. Most of the time, what we desire is what we have been told to desire, which then becomes internalized and starts to appear to us as our “own” desires. The urge (necessity) to satisfy those desires – often imposing them in an aggressive way unto others – is what we, then, call “freedom.”

FS: Did you ever encounter a sense of disillusionment or worldview conflict in your involvement with the art world that has led you to disengage from pursuing a career as a professional artist?

DD: I haven’t been disillusioned, but I did learn quite a bit more, over the course of my later studies, about the actual system of contemporary art. I learned that it is, like almost everything else nowadays, much more about capitalist profit- and agenda-making than about creation. I am happy that my interests led me to art history, philosophy and eventually, to theology and political theory. This helped me understand that creativity and art (as a system and social institution) do not need to go hand in hand, and that the issue of creativity should actually be disentangled from the issue of art. This realization can lead to much more freedom. One can see that human creative capacities are universal, and that one does not need to be an “artist” to be a creator.

FS: It could be said that, in most people’s minds, Orthodoxy and contemporary art are completely antithetical to each other in principle. How do you approach this apparent dilemma? Should there be more of an exchange between Orthodoxy and contemporary art?

DD: Yes – as I have argued in some of my papers and books. There is a lot that Orthodoxy/Orthodox theology can learn and even use from modern/contemporary art, and there is, I think, a lot that contemporary artists can learn from Orthodoxy. Here, in Stockholm, we are about to launch a course in theology for studio art students. In my book The Human Work of Art, I tried to show how some of the most important twenty–century art practices can be relevant for an Orthodox theology of creativity. A dialogue between these two spheres could help contemporary art (in some of its manifestations at least) to get out of the “Babylonian slavery” to capitalism, and could, at the same time, help Orthodox theology rethink the issue of human creative capacities. There is, of course, a risk that such a dialogue can turn into an uncritical theological embrace of everything and anything that seems “in” or “cool,” and such tendencies can be seen among many theologians, including Orthodox. We need a serious and critical engagement with many aspects of contemporary culture – including art – but this needs to be done in a theologically sound way, and not merely because it can make us look “cool.”

FS: Throughout the years, you have worked in a variety of media, including painting, printmaking, performance, video and installations. What role has the icon, as a liturgical art, played throughout the years in your thinking about these various aspects of your artistic practice?

DD: On the one hand, I’ve always thought of icons primarily in liturgical and sacramental terms. “Art,” the way this concept works in the history of modernity, lacks “iconicity” in some important aspects, which also means that it lacks a liturgical or sacramental dimension, at least the way the Orthodox understand these terms. However, and this is where things get interesting, one cannot deny many different attempts at exploring a variety of “spiritual” (often secular-spiritual) qualities in modern and contemporary art. One also needs to consider that an exchange between modern art and icon painting (both traditional and modern) has been a very fruitful one. Orthodox understanding of icons enables us to think of the aesthetic (even very formal) qualities of painting outside the formalist and, in a broader sense, artistic paradigm. However, formal properties and the insistence in modern art on the qualities of materials used for artistic purposes, can be very helpful in rethinking the status and meaning of aesthetic/material properties of icons in return. Finally, when creativity is understood as a communitarian dimension of human existence, many manifestations of modern art reveal their potential for “iconicity.”

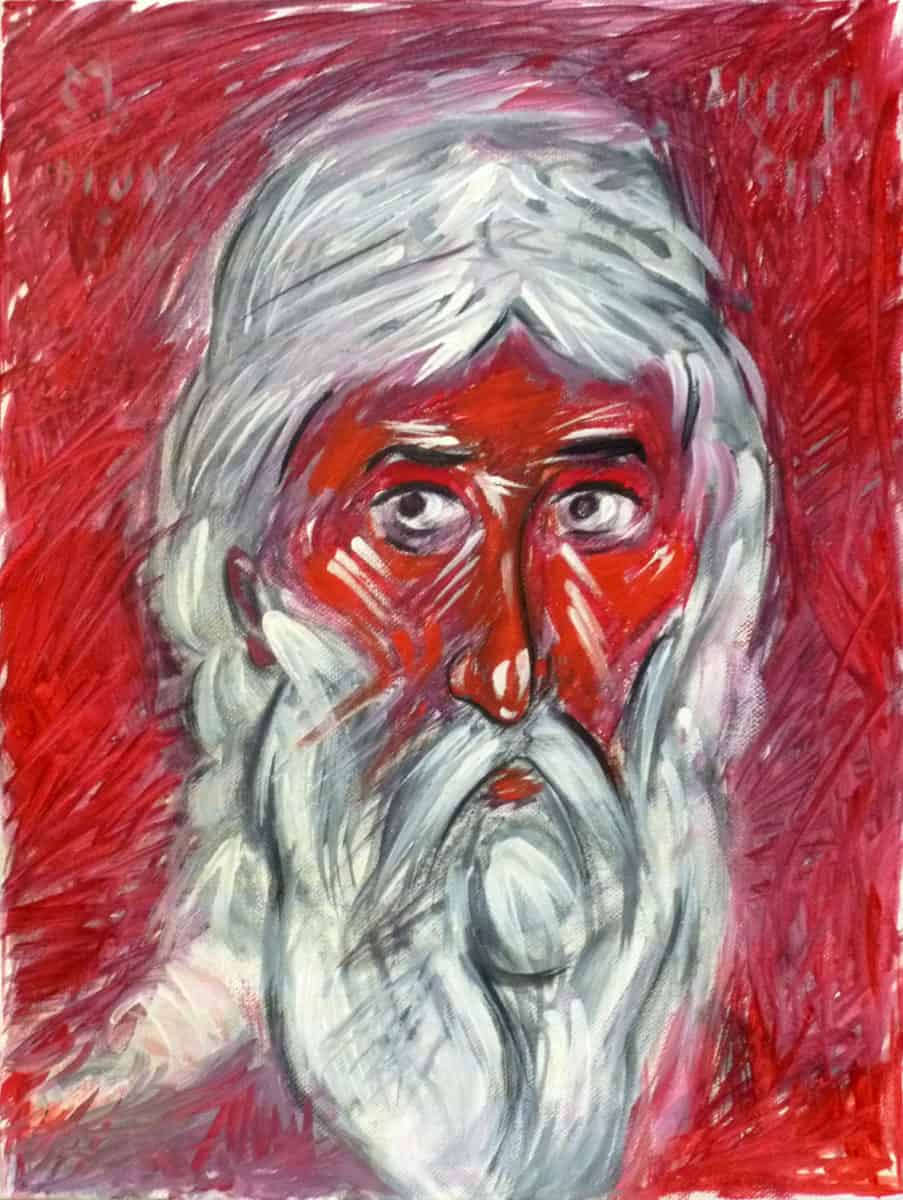

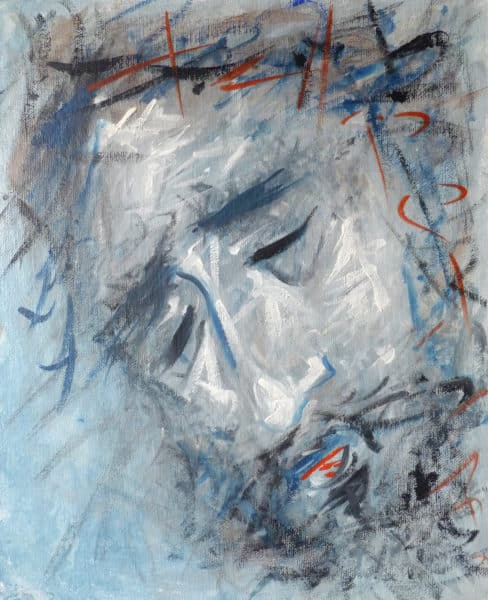

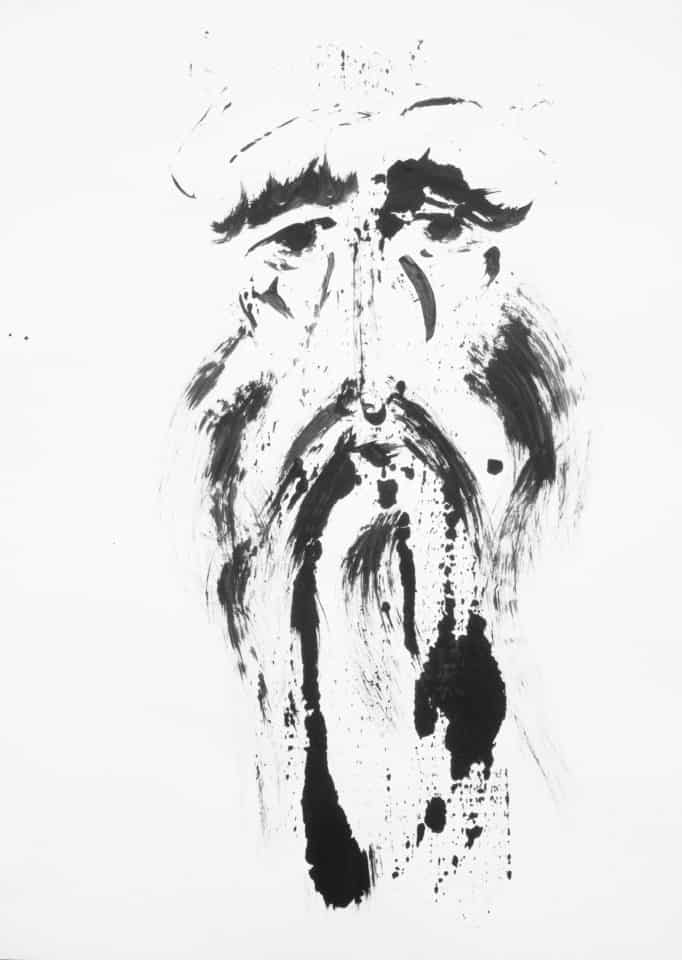

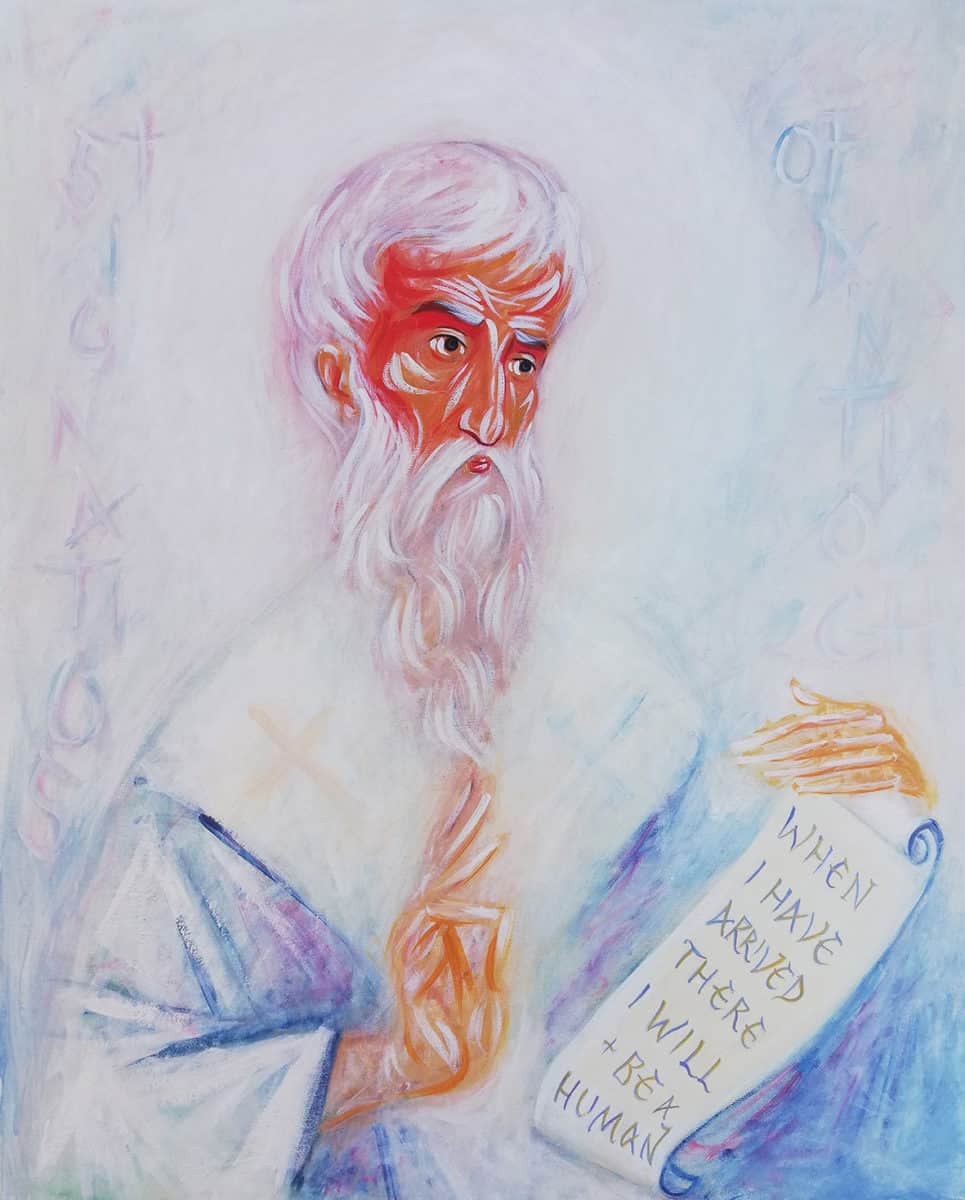

FS: Your icon-like paintings are clearly not intended for liturgical use. So it would be rash to critique them based on that function. They are based on some aspects of traditional types but go further into a very personal domain of interpretation, straddling a border zone between an ecclesial and modern art ambiance. The figures seem to emerge from an active field of potentiality, pulsating with intense energy. There is also a casual way in the handling of the image, with a kind of “anti-aesthetic” expressionism. How do you position these works in light of the icon painting tradition and the domain of contemporary art? To me they seem to resist both traditional and contemporary art strictures.

DD: I would say that they are not necessarily painted for liturgical use (narrowly taken), but many of them are not necessarily a-liturgical either. I call them “icon-like” precisely to preserve that ambiguity, to resist “both traditional and contemporary art strictures” (thanks for that qualification!), and to keep open the possibility that people may look at them, or use them, in the context of liturgy. As we know, there is not one “canonical” style in the tradition of icon painting. Early Christians used the “style” (or, rather, styles) of ancient Roman painting. Later on, we find many other approaches that have become part of the icon painting tradition. My experiments with “icon-like” paintings grew organically from traditional icon painting that I had initially practiced. Then I tried to experiment with the boundaries of what is liturgical art, as different from, say, Church art, what can be non-liturgical but still Christian art, and so on. Another interesting question I’ve been interested in is how the more traditional elements of icon painting can be merged with different painterly poetics to also express something of a personal approach, and a particular worldview.

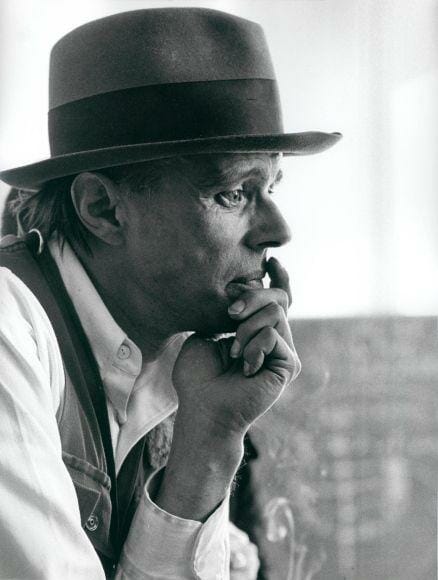

FS: In 2006 you defended your thesis at the University of Freiburg, Germany. If I’m not mistaken, your thesis dealt with the work of Joseph Beuys, and the idea that there are certain Christian implications to his work. Beuys used the phrase, “Every man is an artist.” This reminds me of a parallel statement, often uttered by the historian of medieval and Indian art, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy: “The artist is not a special kind of man, but every man is a special kind of artist.” These statements tend to go against the grain of the elitist, modernist conception of the artist as a prophetic genius and art as the manufacturing of aestheticized commodities. Why was Beuys so important to you at the time? Does he still exert influence on your work today?

DD: Beuys was very important to me since I found many parallels between his work and the way I understood the method and (potential) goals of art. First of all, he also tried to overcome the boundary between art “theory” and “practice,” merging one with the other on multiple levels. Second, he saw the artistic (i.e. creative) potential as part of who we are as human beings, not something exclusive, reserved for certain individuals. Moreover, he saw the realization of this potential as a communitarian practice, in a double sense: as something that happens in-between individual human beings (where there are no spectators but only participants, collaborators in a creative practice), and as something that is ultimately directed at society as a whole. That is Beuys’s famous concept of the “social artwork” (sozialle Plastik/Skulptur). He also placed himself within the Christian tradition and, one can argue, his own understanding of the communitarian/social dimension of human existence has been to a great degree influenced by that tradition. So, the universal (and emancipatory) character of human creative capacities – that every human being is a creator (although not necessarily an “artist” in a more conventional sense), the communitarian dimension of artistic/creative work (which can then lead us also into the perception of the ecclesial character of human creative capacities), and the political dimension to such creative practices – all of these were the points of my dialogue with Beuys. Aided by Berdyaev, of course.

FS: Is our inherent capacity as creators to be understood as the means by which we actualize our theosis, uniquely and dynamically, in each one of us? The way through which we partake of the eschaton here and now, yet something to be fully realized in the Kingdom of God?

DD: Yes, that is how it can be understood from an Orthodox theological perspective.

FS: This inevitably brings us to the topic of our received assumptions concerning art and artistic practice. Thus, as you often point out in your writings, the notion of “Fine Art” is a recent invention, formulated as recently as the 18th century. Can you please summarize for us the development of the modern conception of “Art” and how this is often taken for granted as the “correct” way of evaluating a creative act, irrespective of its historical or cultural context?

DD: “Art,” the way we intuitively understand this concept nowadays, is both an ideological and social-institutional construct. The word is not new – art, from Latin ars (or Greek τέχνη), has been used in a variety of ways. Its primary meanings are not those that we nowadays use when we speak of “fine” or “creative arts.” Art/ars/τέχνη primarily referred to “skill,” “craft” and “knowledge.” Only over the course of early Modernity, through a long and complicated process, have we arrived at the idea that there are “fine” as opposed to “liberal” and “mechanical” arts. Since the nineteenth century, it became common to use “art” to refer to those “autonomous” and “fine” arts (i.e. those “arts” that are based on aesthetic qualities), while other “arts” obtained different names – “sciences,” “crafts,” etc. Parallel to this process, there was the development of an entire set of institutions that had not existed before – museums, galleries, art academies (as opposed to guilds), as well as new disciplines, such as aesthetics or art history. With Romanticism the new concept of art was finally inaugurated as a uniquely modern Western concept, which, of course, became globalized in the meantime. Through Western imperialism, both the socio-economic and the mental-ideological, the modern Western concept of “art” was retroactively applied to the newly invented “Western history,” and was also applied to the rest of non-Western artifacts, when Westerners would codify a variety of things according to their own conceptual apparatus, only include them into one “universal” (but in actual reality particular modern Western) history of art and, for that matter, history of the world. Of course, Westerners remained, for a long time, the sole codifiers and interpreters of these histories.

FS: Where does the icon fit into the ideological developments you have just delineated? How does it stand apart from the fine art paradigm and what alternative conception of artistic practice does it offer?

DD: It does and it doesn’t. It does not stand apart from this paradigm insofar as many Orthodox priests, artists and theologians use those modern concepts such as “art” or (autonomous) “aesthetics” in regard to icons, completely unaware of their long and complicated history. Icons are also part of this paradigm in the sense that many art historians and artists look at icons as just another manifestation of “art,” i.e. what we expect to see when we look at those paintings through the lenses of the modern Western paradigm of what “art” is. Part of icons’ being in the art world is also the very real presence of icons inside modern galleries, museums, educational programs, or art history books. Through this institutional presence, icons have been influencing the modern/contemporary art world, and the art world has been influencing icon painting. However, icons also do stand apart from this story as their meaning (qua icons), from the Orthodox theological perspective, is revealed only within the liturgical context, and not inside a museum or a gallery.

FS: Would it be fair to say that the rhetorical arguments in favor of beauty — e.g. “Beauty will save the world” — often advanced in support of “traditional art”, in opposition to the “aberrations” of modernism – is in fact ironically partly indebted to the modern paradigm which gave rise to the notion of “art for art’s sake” in the first place? In other words, perhaps what we have here is the inadvertent conflation of beauty as a theological category with Kant’s disinterested aesthetic contemplation.

DD: Indeed. Many of those theologians who cannot stand modernism and modern art for its “distortions” of “pure art” or “pure beauty,” are completely unaware that their very understanding of what “art” is/supposed to look like, is just a specific case of the modernist approach, virtually unthinkable outside the framework of modernist paradigms. That is one of the reasons why I felt it important to supplement the famed line you quoted from Dostoyevsky with another one – that “beauty” may “destroy the world” as much as it can “save” it.

FS: Of course, not all “beauty” is by default to be simplistically taken for granted as the manifestation of the Good and the True. What kind of beauty do you have in mind as a “destructive” agent in the world?

DD: I was actually just paraphrasing Dostoyevsky – in the same novel in which we find the famous line about beauty “saving the world,” there’s another line about beauty which can “turn the world upside down.” The way I use this concept is to point to the “beauty” which turns us into passive consumers (with our consent, to be sure), in which there is no depth, no room for freedom. Think, for instance, of the “beauty” we are presented with in TV commercials or through the very medium of social networks. This beauty captivates the gaze and provides a fantasy framework within which we interact with ourselves. An alternative approach to beauty (which I once called the “aesthetics of the cross”) stimulates us to get out of our self-centeredness, our autism, to open up for someone/something else.

FS: How can we best develop a sense of icon painting practice that is neither dispersive and corrosive in its permissiveness towards experimentation, nor insular and stultifying in its ideological stance, based on a misconstrued notion of ossified tradition?

DD: I don’t think there is a universal recipe, and I don’t think there should be one. It requires an active engagement of painters, priests, theologians, and church communities – the latter being particularly important. Icons are made primarily for liturgical communities, so it is important that, regardless of their formal properties, local communities perceive the paintings that decorate their church buildings as icons. An icon is not made by a painter, but by the function it performs within the Church and, ultimately, within the history of salvation. That is why an artist, or a “genius,” cannot produce an icon, even though he or she can produce artworks of admirable aesthetic properties. In this case, as in anything else concerning the Church and Christianity, more self-emptying love, more prayer, more knowledge, more freedom, creativity and responsibility, and less fear and (bad) dogmatism and fundamentalism – is the way to go.

FS: Is it possible to have an art that brings us to the threshold of the mystery of the Sacred within the framework of the contemporary art paradigm?

DD: I very much doubt it – if by the “framework of the contemporary art paradigm” we mean the currently existing capitalist art market. If by “contemporary art” we simply mean a variety of media that are used for a variety of creative practices – I think it is possible to create works that bring us to the threshold of the mystery of the sacred. Many buildings do so; so do many movies or books. All of those creative practices ultimately lead us toward other human beings and the rest of the creation, they lead us toward an ecstatic presence, toward a “human work of art.” This ecstatic “going out” of ourselves – that is what appears to me as the threshold of the mystery of the Sacred.

FS: Thank you very much, Davor, for such an engaging conversation.

For more information on Davor Džalto’s work visit his website.

astounding.

I am moved by this work! Truly amazing. Thank you.

The works of art shown in this article have touched me in deeper, inner places where words cannot immediately reach. The conversation was also very interesting, and lead me to a dimension of thinking not easily available to the us in the modern world.

simply incredible work