Similar Posts

Introduction

This article is the second in a series documenting the mural project at St John of the Ladder Orthodox Church in Greenville, South Carolina. This beautiful temple was designed by Andrew Gould. The previous article presented the murals in the two smaller rooms adjacent to the church’s sanctuary. Here, I will present the recently completed murals in the narthex.

Narthex Iconography

The narthex is a foyer on the western end of the church. It acts as a transitional space between the outside and the main worship space. On the most basic level, this space allows us to ‘land’ in the building. Our eyes adjust, families regroup, we remove coats and hats, buy candles to light in the church, and so on. The lighting is generally dimmer here, and people quiet down and gain focus before entering the nave.

Liturgically, the narthex is where baptisms and funerals historically took place – services marking major life transitions. Blessings of water take place here, as well as exorcisms, betrothals, and other transitional moments.

Spiritually the narthex marks the passage from the chaos of worldly cares inward towards the kingdom of God.

All of this informs the subject matter of narthex iconography, which carries themes of transitions, preparation, and purification. Now we will look at how these themes work in the narthex at St John of the Ladder.

The East Wall

For the narthex at St John of the Ladder, we chose the theme of Baptism to guide the mural program. Baptism is the sacramental action by which those outside enter the church. In a sense, we reenact this each time we enter the church building for worship.

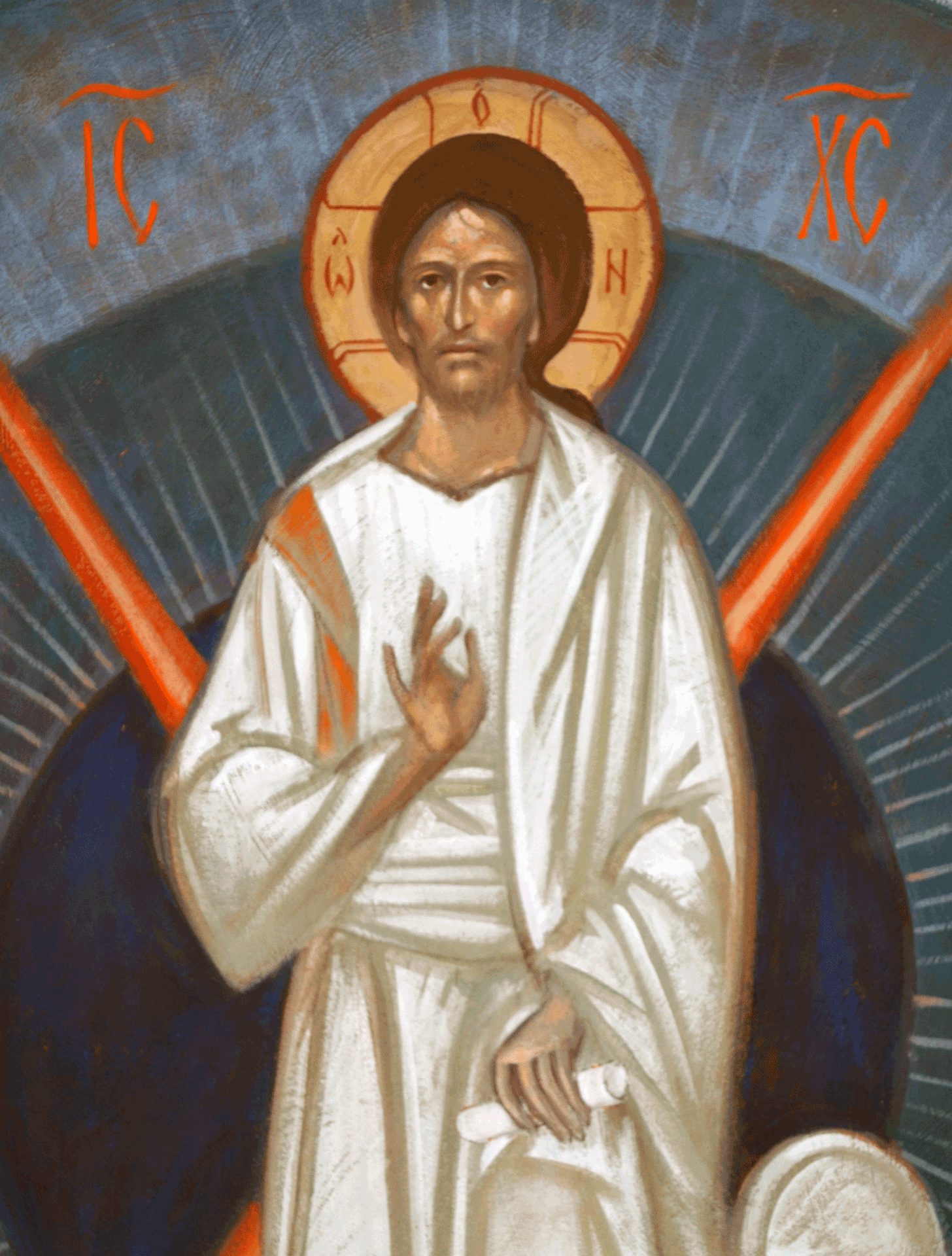

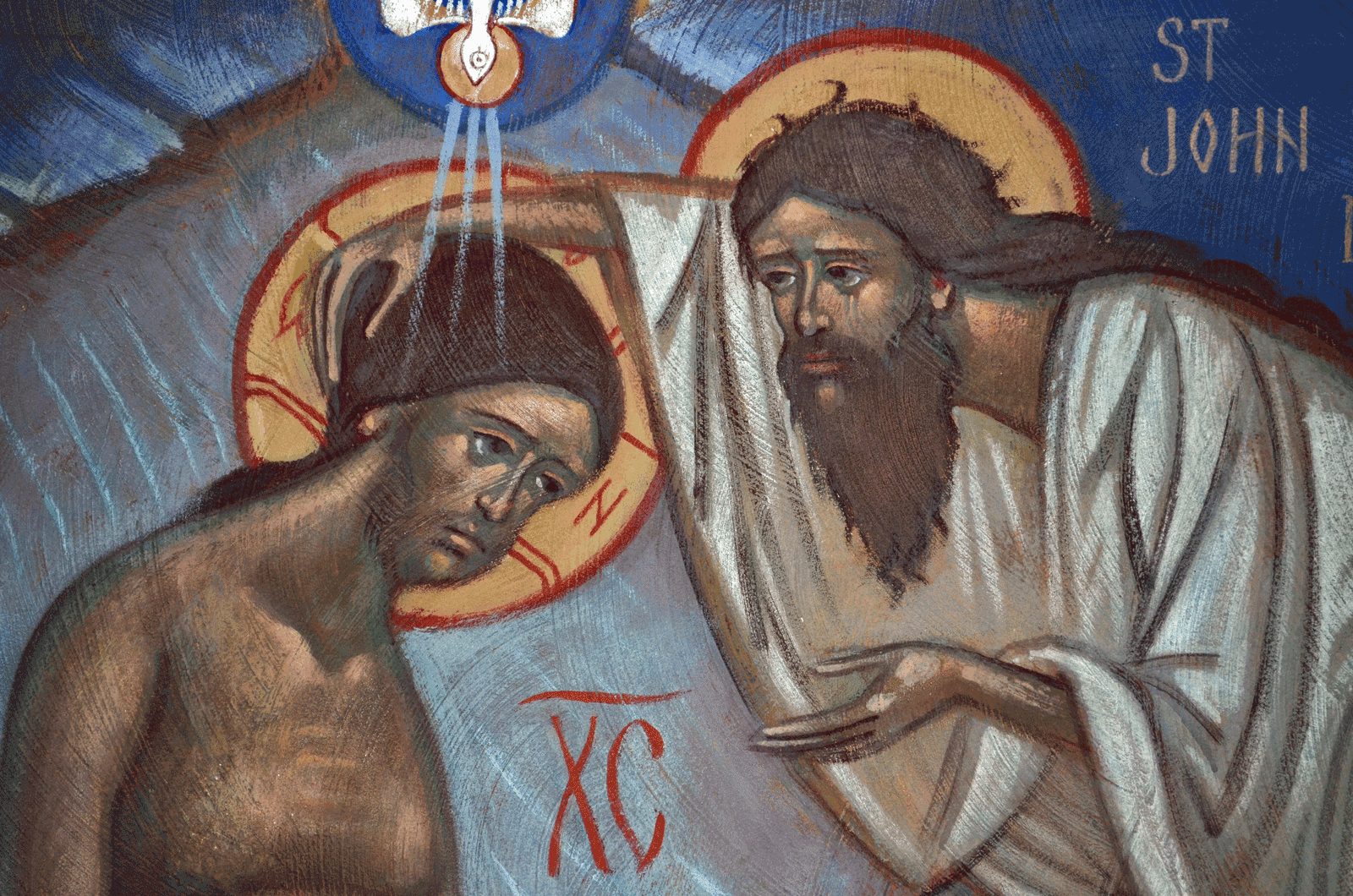

We chose the icon of Theophany to go on the east wall, directly above the doorway into the nave. This is the first mural to meet your eyes upon entering the building, and it beckons you forward. Christ’s descent into the water directly interprets our act of entrance. His figure exemplifies this act. His nakedness indicates purification from any baggage, and signifies death to the old, worldly way of life and rebirth to the new, heavenly life. He shows volition as he strides towards John the Baptist, and submission as he bows his head. His hand blesses the water, and those who with him pass underneath.

The depiction of Theophany is closely based on the Gospel text. The semicircular ‘glory’ at the top indicates the presence of the Father. The Holy Spirit in the form of a dove hovers over Jesus’ head. This image of the Spirit hovering over the water resonates both with the Genesis creation story (Genesis 1: 2), and the dove from the story of Noah (Genesis 8: 6-12). It is an image of God initiating a new beginning.

St John the Baptist’s figure also shows us the way as we enter. He is reluctant to approach because of his unworthiness. But, in obedience to Jesus’ call, he comes forward to participate in God’s plan. We follow his example as we approach the sacred space, and especially as we approach the chalice for Communion.

On one side, a group of angels attends the Baptism. The Theophany service texts frequently speak of their presence. On the other side, a group of people prepares for Baptism by John in the Jordan. They look on as they remove shoes and garments in preparation. This scene occasionally appears in Theophany icons, especially where the composition is strongly horizontal.

Group of people preparing for Baptism. Apostles Andrew and Peter appear also, as described in the Gospel.

Finally, two small figures appear by Jesus’ feet. A quote from Ouspensky’s The Meaning of Icons explains their presence:

These details illustrate the Old Testament texts, which enter into the divine service of the festival, and are a prophetic prefiguration of Baptism. “The sea saw and fled: Jordan turned back” (PS.cxiii, 3). The male figure—an allegory of Jordan—is explained by the following text: “Elisha turned back the river Jordan with the mantle, when Elijah had been taken up, and the waters were divided hither and thither; and the bed of the river was to Elisha a dry pathway, as a true type of Baptism, by which we pass through the changing course of life.” The female figure is an allegory of the sea and refers to the other prefiguration of Baptism‑the crossing of the Red Sea by the Jews. 1

The North and South Walls

The two scenes indicated by Ouspensky’s quote here adorn the two side walls of the narthex, north and south. On the north wall, Elijah and Elisha cross the Jordan river, and Elijah goes up in the fiery chariot. On the south wall, Moses leads the Israelites through the Red Sea, as Pharaoh and his men are deluged. The water in each scene continues into the Jordan in the Theophany mural.

We found these two scenes to have wonderful potential as parallel images. Both involve chariots and horses; here ascending in fire, there descending in water. Each scene has a strong forward motion, as is appropriate for north and south walls. This motion resonates with our eastward movement into the worship space.

In the middle of each scene, the main character moves forward, towards east. However, each looks back towards the center of action, and towards us, leading the way forward with their hand. The very center of each composition shows an action of transition. Elijah passes his mantle to Elisha, passing on his ministry. Likewise, Moses strikes the sea with his staff to part the water, making a way through.

The angel in Elijah’s scene leads visually into the group of angels attending Christ’s Baptism on the east wall. Likewise the group of Israelites lead into the group of people preparing for Baptism.

West Wall

In general, west-facing iconography in a church relates to the act of departing from the liturgical space. Dismissal and departure are key dynamics in liturgical services, and the iconography we encounter as we leave guides and interprets this action.

We chose the Lord’s Transfiguration for the west wall of the narthex, directly above the doorway leading to the outside. The Transfiguration is unusual for a west wall, but it works surprisingly well in this program.

With scenes of Moses and Elijah on the adjoining walls, the Transfiguration brings the program together nicely. As in the Gospel account, Moses and Elijah appear on either side of Christ. Moreover, the Transfiguration answers to the Theophany in meaningful ways, particularly in view of the baptismal function of the Narthex.

These are two of the great revelations of Christ’s identity, which prefigure the fulfillment of his work. In the Theophany we see Christ as naked, submitting himself to Baptism. He thus reveals himself as the one who would submit to death on the Cross. And in the Transfiguration we see the Christ who would rise from the dead. His death is revealed as voluntary as he is clothed in glorious light. Juxtaposing these two scenes brings out the resonance of Theophany with the baptisms that will take place in the narthex. After submersion in the water, we clothe the baptized in white robes.

Though it is unusual for a west wall, the Transfiguration also has rich potential for interpreting the act of departure. We understand the Transfiguration as a change, not of Jesus’ form itself, but of the disciples’ ability to see his true visage more clearly. If we could see with a pure heart, all creation would appear transfigured with the presence of God.

This is the change of vision which the liturgical life cultivates in us, gradually over time as we participate. At the liturgy, following Holy Communion we sing “we have seen the true light,” just before the dismissal. As we depart the building, just before our eyes meet the bright daylight again, the Transfiguration icon reminds us to see the people and circumstances we meet in this new light.

Door exiting the narthex to the outside. (This mural had to incorporate the exit sign, which may be fortuitous. The Gospel says that at the Transfiguration, Jesus spoke to Moses and Elijah of His “exodus” – a Greek word that can mean exit.)

Notes

I painted these and other mural projects with mineral silicate paints. These paints have the same desirable visual qualities as traditional fresco. They are, however, more durable for both interior and exterior applications. They are also much simpler to use. I believe this is the best option in most cases for church murals. For any readers whose parish may be considering iconography in the future – please learn about silicates before making major decisions! I am happy to share information about this kind of paint with those who have interest.

Wonderful and inspiring work! I would like to know more about the silicate paint, including how one might prepare a board for an icon on which to use it. Is it from the KEIM company? I wrote them for information, and am waiting to hear. Thank you.

Thanks, John! Contact me by email at seraphim.okeefe@gmail.com and I can send you some information.

Wonderful work, Seraphim! I look forward to seeing the completed work this summer while I’m doing my CPE at Prisma Health.

Beautiful work and beautiful words! Great work tying baptism to the prophets. Makes one want to glance at the frescoes at Dura Europos again.

Breathe taking, each and every one. What a gift to us Seraphim! I sincerely thank you and am grateful to have you in our lives.

Truly God-Inspired work, Seraphim! Thank you so much for your loving service!

Thank you for your service to the church Seraphim, and for sharing these marcellus works. What a lesson.

By putting the forerunner on Christ’s left and the other angels on His right you reversed the usual orientation of the theophany icon. Do you mind sharing why? As you enter the church this places Elijah on your left and Moses on your right, just as when you look west at the transfiguration. However this configuration breaks the continuity somewhat between the transfiguration and adjoining walls; Moses in the transfiguration is next to Elijah at the Jordan, Elijah next to the red sea. Just curious on your thought process, how it all came together.

This has opened up Elijah’s ascension for me in many ways. I love your use of color all around, and look forward to seeing the nave.

Thanks for your very attentive comment; yes, this arrangement is the product of a lot of consideration. Starting with the Transfiguration: this composition has been fixed since early on, wherein Moses appears on Christ’s left, and Elijah on His right. You will almost never see them switched. Iconography on a western wall is composed to be seen while facing west, while all the other walls are to be seen while facing generally eastward. Thus, as you noticed, the scenes of Elijah and Moses on the north and south walls are on the same side, right and left, as in the Transfiguration icon. While it is true, as you note, that this places each prophet at the Transfiguration closer to the other prophet’s scene; in effect this ends up being more conducive to continuity, because each prophet is facing his own scene, rather than having his back to it.

We also have a side chapel dedicated to Moses and the Burning Bush on the south side of the church, and we wanted the Moses scene to be on the same side.

As for the Theophany, this composition has a lot more variation in the tradition. Most place St John the Baptist on Christ’s right, but there are many exceptions. There are also many variations of the other elements, such as how many angels are attending. So, we wanted the continuity of the group of angels with the Elijah scene, and the group waiting for baptism with the Moses scene, as I described above. Also, having Christ approaching from our left towards our right reads more as forward motion to people who read from left to right, and this creates a more natural mimesis for the act of entering the doorway below.