Similar Posts

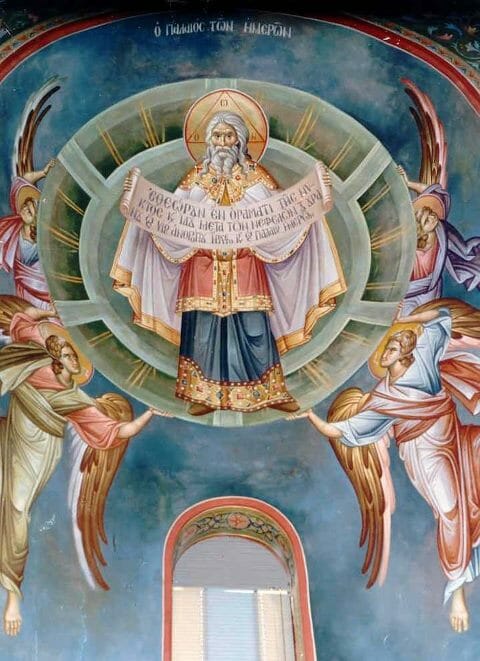

Sometime ago, a friend sent me an image of the Ancient of Days that is being painted in a Greek Orthodox parish in Montréal, Québec, Canada. He wanted to know what I thought of it. The first image was not yet finished and the seond one is finished. I wrote him back the following comments.

Second version of the Ancient of Days

Hello Angelo,Reference : Daniel 7: 9-22

The essential questions in this passage and for the image of the Ancient of Days are these: Who is the Ancient of Days? And who is the Son of Man who comes close to him to receive a kingdom? This passage from Daniel has historically been used to theologically justify images of God the Father, alone or in various forms of what is called the New Testament Trinity as opposed to the Old Testament Trinity that is the Hospitality of Abraham. The so-called New Testament Trinity has various forms but always shows an old man with a white beard, an adult man or a boy, and a dove. According to this interpretation, the old man, the Ancient of Days, is the Father; the man, the Son; and the dove, the Holy Spirit. These images and their theological justification have become so common in the Orthodox world that nobody, almost nobody, questions them. But I, being impertinent, rebellious, and–imagine Orthodox, I hope–wish to rise up and challenge both the image and the theological explanation as being contrary to the Holy Tradition.

We know from historical and iconological studies that both the image of the Ancient of Days as God the Father, alone or in the so-called New Testament Trinity, and its theological justification based on Daniel do not come from the Orthodox Church’s tradition. It is only around the late Middle Ages that the image and its justification make their appearance in the Orthodox world, and the source is the Latin Catholic West. For several centuries, western painters had been painting various forms of the Trinity, which were eventually justified by an appeal to Daniel and his vision of the Ancient of Days. During the period of what is called the Western Captivity, when Orthodox all over the world swallowed nearly everything that came from the Latin West as “better” than the “old-fashioned” Orthodox images and theology, this image and its justification made great inroads into the Orthodox consciousness. And this to such an extent, that people forgot the real and genuine Holy Tradition of the Fathers. And what is that Tradition?

Briefly, it is that the Logos of God the Father, the Son, who became incarnate in the historical Jesus of Nazareth, is the one, the Person, who reveals himself, imperfectly, vaguely, as through a mirror, just a little bit, in the Old Testament. Who spoke to Moses on Mount Sinai? Who spoke to him in the burning bush? Who is the creator that Genesis talks about? With whom did Adam and Eve walk and talk in the Garden of Eden? Whom did the prophets see and hear in their visions? The unanimous Holy Tradition of the Orthodox Church says that it was the Divine Logos, the Son, the second Person of the Trinity, not the Father. The Son reveals the Father and the Spirit both in the Old Testament, “darkly” and openly in the New Testament. “And he taught us how the Law and the Prophets spoke about him.” So the question is this: Whom did the prophets, and particularly Daniel, see in their visions? The general answer from the Fathers is that they heard and saw the Son and not the Father. Therefore, this general principal of interpretation–the Son reveals himself darkly in the Old Testament–should be enough to answer the question as to the identity of the Ancient of Days.

But then, those who want to justify the images of God the Father say,

But look at the passage of Daniel 7: 9-22, and you’ll see that the Ancient of Days, despite the general principle of interpretation mentioned above, is not the Son, the Logos, but the Father, and therefore since the Father made himself visible, we can paint his image.

They say that this person, the Ancient of Days, appeared in glory, and then someone like a Son of Man came up to the Ancient of Days and received an eternal kingdom. Since the title Son of Man is obviously a designation for Jesus, the incarnate Logos, who “approaches”, comes up to, moves toward, the Ancient of Days, there are obviously two persons here: one, the Son, the Logos, the Son of Man, and the other must therefore be the Father. They say, “There, you see, the image of God the Father, shown as the Ancient of Days, is biblical, OK, and Orthodox.”

I must admit that that sounds pretty convincing, doesn’t it? It is so convincing that for several centuries Orthodox people simply accepted it without question. But let’s take a look first of all at Daniel 7: 9-22. What is the scene? What is Daniel talking about? What is his dream a vision of? It is quite clear from reading carefully the passage that we have a vision of the final judgment, when all the bad guys, the beasts, will be destroyed and the saints of God will be established in peace. Verse 9: 7 starts out “The thrones were set up and the Ancient of Days sat down.” Where and in which capacity? As judge at the final judgment: “until the Ancient of Days comes and the judgment is given in favor of the saints of the Most High.” Now from the Orthodox point of view–I would even say from the general Christian point of view–who is the Judge who will judge all people at the Last Judgment? There is no question that it is Christ, the Son, the Logos of God, the second Person of the Holy Trinity. “The Father has given all judgment to the Son…” So right from the beginning, even before the Son of Man appears, we have to identify the eschatological Judge sitting on his throne of judgment as the Son.

But then what do we do with the Son of Man who approaches the Ancient of Days to receive the eternal Kingdom? Isn’t it obvious that he is a different person from the Ancient of Days? Well, is it so obvious? Let’s not forget that we are dealing with a vision and a dream, so we are already in a realm where the logic of our waking world doesn’t really apply. Second of all, we’re dealing with a dream about an event that has not yet happened and one that will take place after the general resurrection, events that we can even now only talk about in symbolic, poetic language, a language that doesn’t obey the logical laws that govern our life here and now. So it is not obvious that we are dealing with two distinct persons here, one the Father and the other the Son. It is completely possible, according to the logic of dreams and eschatological visions, that two figures can represent the same Person, in different aspects of his being, or even that one figure can represent two or more persons, again following the logic of symbols and dreams. I would say that from the very beginning of the passage in Daniel, the Ancient of Days is the eschatological judge–and from the Orthodox perspective, that must be Christ–and the Son of Man can also be seen as the Son, Christ. We have here then two figures who represent two aspects of the same person. The Ancient of Days on his throne of glory, judging the beasts, and the Son of Man in his humility as incarnate who receives the eternal Kingdom. “But Father,” you may say, “the Ancient of Days then is giving the eternal kingdom to himself.” Well, that is alright. The language and the imagery are simply those which the prophet chose to express his vision. We know that there are two aspects to the Incarnation: the Lord of glory and the humble servant. Putting ourselves into the mind set of dreams and visions, we should not be surprised that two figures symbolically represent two aspects of the same reality, the same Person.

So then, it is not necessary to interpret Daniel’s vision as two distinct Persons: the Father and the Son. It is completely consistent with our theological principles and dream language, to see that two aspects of the same person are “dramatically” represented. This interpretation also avoids a gross violation of the accepted rule that the Son reveals himself in the Old Testament. There is no other passage in the Old Testament in which it is said, by the Orthodox, that the Father became visible. And we know also that no other Biblical passage is sited by those who want to see the Ancient of Days as the Father to justify direct images of the Trinity.

So then are all images of the Ancient of Days to be banned as contrary to Holy Tradition? No, indeed, but they must be clearly identified as the Son so that the principle is preserved that it is the Son who reveals himself in the Old Testament. There are many examples of this kind of image in the Orthodox Tradition: an old man with a white beard with a halo around his head with a cross in the halo and the Greek words, HO ON, meaning the existing one, Yahweh. This is what the speaker said to Moses when Moses asked what his name was: Yahweh in Hebrew and Ho On in Greek. “I am the existing One” or something like that. Why is Ho On in the halo of nearly all icons of Christ? Those words tell us that the Church says that this man, Christ, is also the One who spoke to Moses and the other prophets including Daniel. Now when we look at the image that has been/will be painted in the Montreal parish, we see that indeed there is a halo with Ho On in it but there is no cross, which is another way for the Church to say that this man, Jesus, really died on a cross. So there is one good point, Ho On, and one bad point, no cross, for this particular image. Another thing, the triangle in the halo. That sign is not rooted in Holy Tradition but is a masonic symbol that was also imported into the Orthodox tradition, but has no place. Sometimes you also see “the all seeing eye” as on American dollar bills, but that has no place in Orthodox iconography. Another point against this image. So the word I would use to characterize this image is ambiguous and as such it should be redone so as to clearly show the Church’s teaching about who the Ancient of Days is. If the triangle were removed and a cross put in its place and maybe even IC XC put by his head, that would remove all ambiguity and would be very good. As is, however, I would not accept it as being faithful to Holy Tradition.

Well, Angelo, I’ll bet you didn’t expect to get such a long answer to your question, but you have to realize that our iconography is not just pretty pictures on the wall, like a museum, but icons, canonical icons, express in lines and colors, the Church’s teaching. We must therefore be vigilant so as not to support “heretical” or ambiguous icons that will only confuse people instead of teaching them properly. Now I’m now going to read the paper. Have a nice day.

In Christ,

fr.Stephen Bigham

PS. Since I received the first image of the Ancient of Days and wrote the above, I received the second image which has IC XC. That is a significant addition and eliminates the ambiguity as to the identity of the figure. It is therefore now acceptable, even though I still don’t like the triangle, but I can live with that.

[…] https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/letter-to-an-iconographer-on-the-ancient-of-days/Monday, Mar 4th 9:00 amclick to expand… […]

The only problem with interpreting the Ancient of Days in Daniel 7 as being Christ is that this has no basis in the Fathers or the Services of the Church, which say quite the opposite, for example:

“The Son of Man shall come to the Father, according to the Scripture which was just now read, “on the clouds of heaven,” [Daniel 7:9] drawn by a stream of fire [Daniel 7:10], which is to make trial of men. Then if any man’s works are of gold, he shall be made brighter; if any man’s course of life be like stubble, and unsubstantial, it shall be burnt up by the fire. And the Father “shall sit, having His garment white as snow, and the hair of His head like pure wool” [Daniel 7:9]. But this is spoken after the manner of men; wherefore? Because He is the King of those who have not been defiled with sins; for, He says, I will make your sins white as snow, and as wool, which is an emblem of forgiveness of sins, or of sinlessness itself. But the Lord who shall come from heaven on the clouds, is He who ascended on the clouds; for He Himself hath said, And they shall see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven, with power and great glory (Catechetical Lectures, Lecture XV, NPNF2, Vol 7, page 110).

“Let us, however, resume once more our theme. The Lord said to my Lord, Sit at my right hand. Do you see the equality of status? Where there is a throne, you see, there is a symbol of kingship; where there is one throne, the equality of status comes from the same kingship. Hence Paul also said, “He made his angels winds, and his servants flames of fire. But of the Son: Your throne, O God, is forever.” Thus, too, Daniel sees all creation in attendance, both angels and archangels, by contrast with the Son of Man coming on the clouds and advancing to the Ancient of Days. If our speaking in these terms is a problem for some, however, let them hear that he is seated at his right hand, and be free of the problem. I mean, as we do not claim he is greater than the Father for having the most honorable seat at his right hand, so you for your part do not say he is inferior and less honorable, but of equal status and honor. This, in fact, is indicated by the sharing of the seat.” St. John Chrysostom, Commentary on Psalm 110

The Octoechos, Tone 5, Midnight Office Canon to the Holy and Life Creating Trinity, Ode 4, first troparion:

“Daniel was initiated into the mystery of the threefold splendour of the one Dominion when he beheld Christ the Judge going unto the Father while the Spirit revealed the vision.” HTM Pentecostarion (which includes this text from the Octoechos), p. 270

“Μυείται τής μιάς Κυριότητος, τό τριφαές ο Δανιήλ, Χριστόν κριτήν θεασάμενος, πρός τόν Πατέρα ιόντα, καί Πνεύμα τό προφαίνον τήν όρασιν.” Ωδή δ’ πλ. α’, ΤΟ ΜΕΣΟΝΥΚΤΙΚΟΝ

And there is a lot more where they came from.

Dear Father John

Thus the Person of the Father can be depicted in icons?

Yup. That which can be seen can be depicted. The vision which Daniel saw, was seen.

“The painting of holy images we take over not only from the holy fathers, but also from the holy Apostles and even from the person of Christ our only God… We therefore depict Christ on an icon as a man, since he came into the world and had dealings with men, becoming in the end a man like us except in sin. Likewise we also depict the Timeless Father as an old man, as Daniel saw him clearly….” (The Painters Manual. 87 (This is a standard Orthodox text on Iconography “compiled on Mt. Athos, Greece from 1730-1734 from ancient sources by Dionysius of Fourna)) Dionysius of Fourna (ca. 1734).

“We must note that since the present Council [the Seventh] in the letter it is sending to the church of the Alexandrians pronounces blissful, or blesses, those who know and admit and recognize, and consequently also iconize and honor the visions and theophaniae of the Prophets, just as God Himself formed these and impressed them upon their mind, but anathematizes on the contrary those who refuse to accept and admit the pictorial representations of such visions before the incarnation of the divine Logos (p. 905 of Vol. II of the Conciliar Records) it is to be inferred that even the beginningless Father ought to have His picture painted just as He appeared to Daniel the prophet as the Ancient of Days. Even though it be admitted as a fact that Pope Gregory in his letter to Leo the Isaurian (p. 712 of the second volume of the Concilliar Records) says that we do not blazon the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, yet it must be noted that he said this not simply, but in the sense that we do not paint Him in accordance with the divine nature; since it is impossible, he says, to blazon or paint God’s nature. That is what the present council is doing, and the entire Catholic Church; and not that we do not paint Him as He appeared to the Prophet. For if we did not paint Him at all or portray Him in any manner at all to the eye, why should we be painting the Father as well as the Holy Spirit in the shape of Angels, of young men, just as they appeared to Abraham? Besides even if it be supposed that Gregory does say this, yet the opinion of a single Ecumenical Council attended and represented by a large number of individual men is to be preferred to the opinion of a single individual man. Then again, if it be considered that even the Holy Spirit ought to be painted in the shape of a dove, just as it actually appeared, we say that, in view of the fact that a certain Persian by the name of Xanaeus used to assert, among other things, that it is a matter of infantile knowledge (i.e., that it is a piece of infantile mentality or an act of childishness) for the Holy Spirit to be painted in a picture just as It appeared in the semblance of a dove, whereas, on the other hand, the holy and Ecumenical Seventh Council (Act 5, p. 819 of the second volume of the Conciliar Records) anathematized him along with other iconomachs from this it may be concluded as a logical inference that according to the Seventh Ecum. Council It ought to be painted or depicted in icons and other pictures in the shape of a dove, as it appeared… As for the fact that the Holy Spirit is to be painted in the shape of a dove, that is proven even by this, to wit, the fact that the Fathers of this Council admitted the doves hung over baptismal founts and sacrificial altars to be all right to serve as a type of the Holy Spirit (Act 5, p. 830). As for the assertion made in the Sacred Trumpet (in the Enconium of the Three Hierarchs) to the effect that the Father out not to be depicted in paintings and like, according to Acts 4, 5, and 6 of the 7th Ecum. Council, we have read these particular Acts searchingly, but have found nothing of the kind, except only the statement that the nature of the Holy Trinity cannot be exhibited pictorially because of its being shapeless and invisible” (St. Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain, The Rudder, pp 420-421 (this is from the admittedly awkward and somewhat flawed translation of D. Cummings, but there is no other translation that is available in English to my knowledge).

I would like to offer something if I may, something that takes a birds eye view if you will. Although I appreciate fr.Steven’s argument here, I do not doubt that the vision of Daniel was interpreted in trinitarian terms (although the fact that Christ is represented with white hair in the book of Revelations makes a muddle of too much explicit interpretation). Now whether the possibility of a trinitarian interpretation of the vision leads to the capacity to represent the Ancient of Days in iconography and identify him explicitly with God the Father is in my view another question altogether. If we look at the general movement of Orthodox art, we can see several things in how it developed. First off, we need to see the deep relation between the notion of incarnation and image and how these two things are bound up. Because the incarnation is the cause of image making and veneration of images then the icon must be seen through the lens of the incarnation. We see this in st-John Damascene’s argument, the 7th ecumenical council, but also in the quinisext council, which pronounced that we represent and identify the Logos as the incarnate person of Jesus Christ and not as he appeared in visions or in Old Testament prefigurations. Now this was followed by the East (but not by the West), which explains why although we see images of the Lamb of God (with haloes) before the quinisext council (in Ravenna for example), these disappear from Eastern art. Like I said, the quinisext council was never accepted by the west, and so a more allegorical type of imagery continued to develop there, coupled with a perception of art which was less attached to the incarnation and veneration, but rather more attached to instruction. Despite this tendency in the west, because its art was very much the child of Constantinople, because it deliberately modeled itself to the art of the East it nonetheless avoided excessive allegory and except for very very exceptional images, the type of God the Father really appears in post-schism western art. This image of God the Father then slowly filters back into Orthodox art. It is not a coincidence that images of God the Father begin to seep into Orthodox art at the same time as images of Sophia which then leads to all the fantastical icons of 17th-18th century Russia. Now the vision of Daniel, as a prefiguration, creates a big confusion when it is thrown into a context of the incarnational theology of icons, when we understand that an icon is ultimately an image of a person. So when you have an image of the Lord Sabaoth, especially when he is represented outside that vision of Daniel, when he is represented as the person of God the Father at the top of an icon or in the western type of him sitting to the left of Christ on a Throne, you will invariably create confusion in Theology and in Worship. That is why the “hospitality of Abraham” icon was preferred by the Moscow councils, because although it is a prefiguration, it avoids the more dangerous confusions by not assigning inscriptions to the angels and by not placing a cross in the halo of the central angel. That is, although this event was seen by Abraham, it is represented as a prefiguration and not as the persons themselves. With the Ancient of Days, this confusion is more difficult to avoid. When we ask: Who is that an image of? The answer is inevitably: It is an image of God the Father, and that is a dangerous thing which leads to deep misunderstandings of what an icon is, of how it relates to the incarnation and in my opinion leads to a dangerous interpretation of the Trinity itself.

The Holy Spirit was not incarnate as dove, and yet we depict him in that way, because that is how he was seen. The “Hospitality of Abraham” icon was decreed by the council of 1666-7 to be an icon of the Trinity, and it decreed that it should be inscribed with the words “Holy Trinity”. It is clear from that Icon, which angel represent which person of the Trinity, but we know that none of the persons of the Trinity were incarnate as angels, but they were symbolically seen as such, and the canons to the Holy Trinity at the Midnight Office make that clear repeatedly.

The Icon of the “New Testament Trinity” is not taking the image of the Ancient of Days out of context, that icon is really an Icon of the vision Daniel saw in Daniel 7. That is why both the Ancient of Days and the Son are always seated in judgment in that icon.

And the icon of the Ancient of Days symbolically representing the Father was used for many centuries, and venerated by many saints, and until about 1950, there was no controversy about it. There is not a single saint that speaks out against this icon.

Father, I have great sympathy for your position in a way and I don’t think anyone who venerates icons with the Ancient of Days to be seen as heretical or less holy for doing so. Although the question was somehow open before as the proliferation of these images in the 16th-17th century attest to, in the very Moscow Council that adressed this issue explicitely, the one you cite as allowing the representation of the Hospitality of Abraham as the proper Trinity icon, the representation of the Ancient of Days is strictly forbidden. Also forbiden is the representation of the Holy Spirit as a Dove outside of the icon of Baptism. This is done with no mincing of words in chapter 45 of the council, in which it is said: “it is completely absurd and inconveniant to paint on icons the Lord Sabaoth”, continuing on to condemn this representation on theological terms.

The Council of 1666-1667 is a very much discredited Council. Among other things, it anathematized the Old Rite. I mentioned it because even that Council decreed that the Old Testament Trinity Icon was a legitimate icon of the Trinity, and decreed that it be inscribed as such. There is no logical reason why the Father can be depicted as an Angel, but not as the Ancient of Days. And if you go to Russia, you will not find any Church of note that does not have the icon of the Father as the Ancient of Days.

Father, I do not want to prolong this discussion as this is not meant to be a forum, and I also find myself in the uncomfortable situation of arguing with a priest, which my bishop might find problematic… I will just make one last remark about the Trinity icon and take my bow. There is a marked difference between the Trinity icon accepted by the council and the “New Testament Trinity”, the difference is that the angels are not identified, there are no inscriptions and there is no cross in the central halo. This means that it is an image in a way, a prefiguration of the Trinity without pretending to represent directly any of the persons, a practice which is grounded on an icon being an image+name as described by St-Theodore the Studite. It is tricky in a way, I admit, but I think it goes farther in avoiding possible confusion than representing images of the Father directly.

The Icon of the Old Testament Trinity unmistakably identifies which Angel is the Father, and which is the Son, and Which is the Holy Spirit. Hanging the case on the lack of inscription seems like a very thin reed to lean upon, because it is inscribed with the words “Holy Trinity”.

If I may reply to both Fr Stephen and Fr John, in a way that responds to the concerns of both and reconciles them, not only to each other, but both of them with the services:

We cannot depict “The Father” (ontological impossibility).

We can depict “The Image of the Father” (“If you have seen me, you have seen the Father”).

Asking your prayers,

Hierodeacon Parthenios

It is interesting to note that the icon of the Ancient of Days always is depicted as having the same face as Christ, but simply as an old man. So on one level you could say that it is an icon of Christ, but that it represents the Father symbolically.

Yes, Fr. John.

I would contend that the broad theological assumptions of your description and of Fr. Stephen’s position CAN be reconciled to one another by this manner of description, which is faithful to all aspects of the One Tradition.

Speaking very exactingly, I would say that this is made clear in the following:

1. The Iconographic Tradition, as actually lived and passed down universally in the Church, is to definitely depict the figure called by us “The Ancient of Days”;

2. The Hymnographic Tradition explicitly points, in some way and in some sense, to the Father as being “indicated in some manner” by “The Ancient of Days” figure in Daniel’s vision (of two figures), and that such depicting/seeing is done precisely “in a sacred and mystical manner”, according to the text of Sunday Midnight Office (Octoechos);

3. The Dogmatic Tradition explicitly denies any possibility of “depicting or seeing the Father”…EXCEPT in our “depicting or seeing of His Exact Image (Jesus Christ)”, who is YHWH or ‘o On’ Who revealed Himself to Moses in the Burning Bush, to Jacob at Bethel, to Isaiah in the Heavenly Temple, etc., as Fr. Stephen pointed out very clearly as being the Orthodox Exegetical Tradition.

So, the depicting of YHWH or “o On”, who appeared to all the patriarchs and prophets of old (see St. Nektarios of Aegina’s book, Christology, starting around page 84 in English), is the depiction, “exactingly speaking” of Christ, Who is HIMSELF “The Image of the Invisible Father”.

Only such a “Christological logic” of depicting “the Image of the Father” can explain all of the elements and aspects of the actual, lived Orthodox Tradition, while avoiding the extremes of “non-depiction/seeing” (which denies the Prophets and Iconographers), or “non-acknowledgement of the Father, in some sense, as present” (which denies the Hymns), or of crass “anthropomorphism” of the usual street-level variety (which routinely denies any sense of the Mystery of Christ or of the “sacred and mystical manner” of His Revelation of His Father).

Also, Fr. Stephen is right, for the very same reasons, that the “TRIANGLE” is a VERY, VERY bad choice to put in the halo of the “Ancient of Days”. That should never be there.

Preferably, the Nimbus should be the “Eight-pointed Blue/Red Star-Nimbus” (which indicates clearly the notion of depicting “in a sacred and mystical manner”), a Christologically and Theologically and Prophetically sound manner of depicting this Mystery.

Or, where appropriate, it could be the “Cruciform Halo w/ o On”(especially for the central figure of Christ in Red-and-Blue Robes in the Rublev Trinity icon).

Interestingly, St. Nectarios of Pentapolis had one of these icons of the Lord of Sabbaoth.

Yes, I think this could reconcile most of the two opposing views we have been discussing, and I agree with your preference for the 8 pointed nimbus, but the triangle image is also used widely. I have never seen the icon that St. Nectarios had (only read about it), but the chances are good it was of the triangle variety.

Thank you for the information, Fr John.