Similar Posts

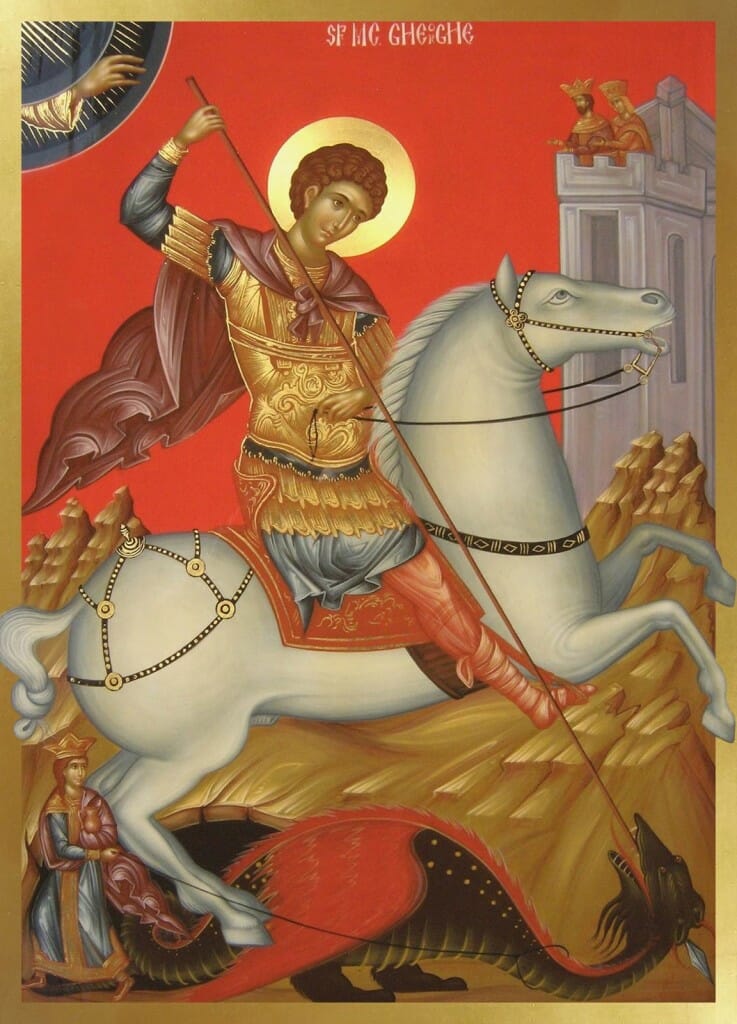

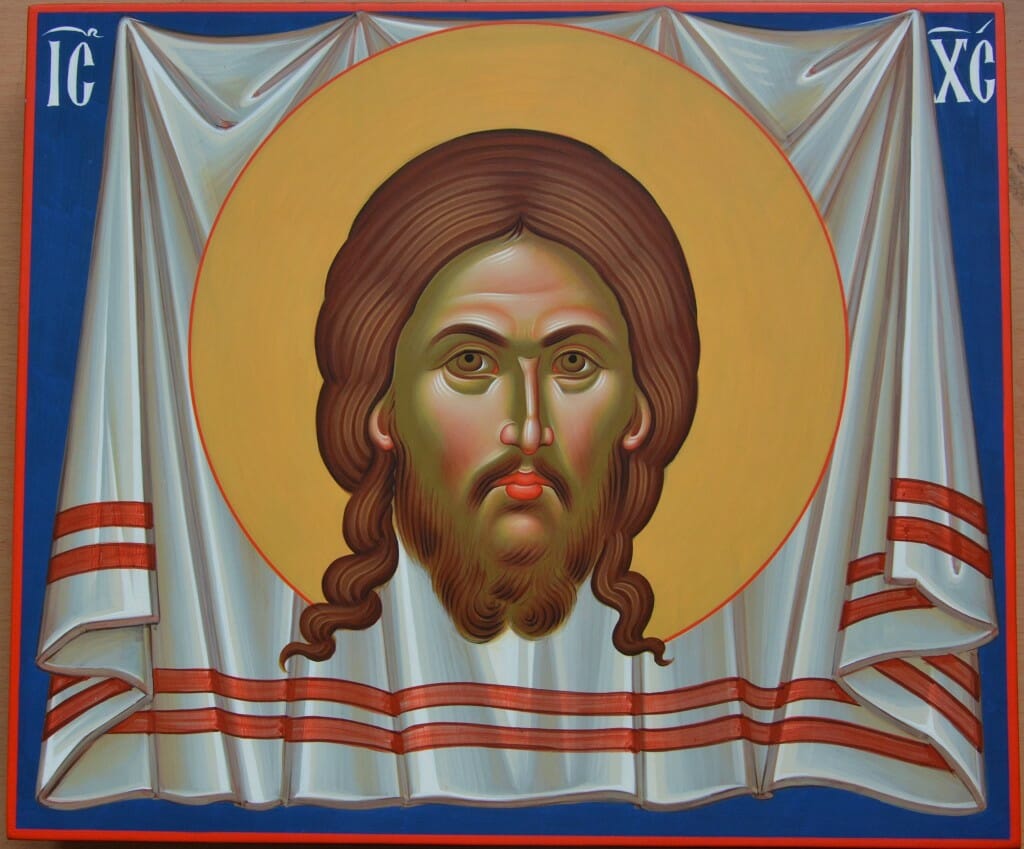

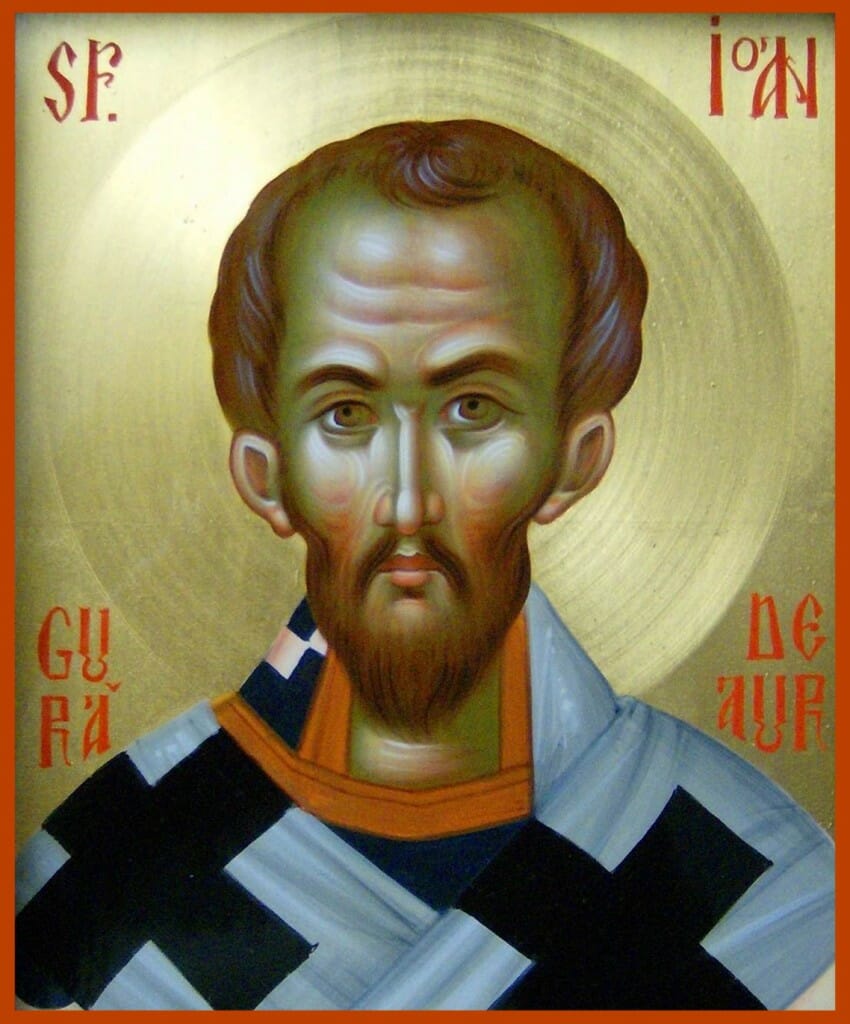

(Editor’s note: A few years ago we introduced our readers to the luscious work of Daniel Neculae, a Romanian iconographer now living in Luxembourg. Last year Daniel gave his first workshop in the US which was attended Marek Czarnecki, veteran American iconographer and teacher himself who agreed to conduct and edit this interview for us.)

On Teaching and Learning Iconography

An Interview With Daniel Neculae

Czarnecki – How were you educated as an iconographer?

Neculae – Before starting University, I learned to draw and paint on my own. I was interested in very realistic drawing and classical painting. I used general subjects at that time, I wasn’t interested in making icons. My only critics were my family. My grandfather was a theologian with a deep love of beauty; he especially encouraged my efforts, but his deepest wish was I become a priest. He taught me how to pray, how to work honestly, to always strive for perfection and absolute beauty. Later, I found all this in Byzantine art.

My preparation began in the church with my spiritual education. Then I studied the techniques of the classical Renaissance painters who attracted me the most. I reproduced their artworks. I think that there is a huge difference between a young man who learns how to draw by studying Da Vinci’s artworks and one who studies drawing after Picasso. In secondary school my teachers were encouraging, but did not have artistic knowledge. I am sure God is always guiding my steps in life, so I see this positively. It motivated me to study more on my own.

It’s important for an iconographer to be an active member of the church and to know its theology very well. I attended an Orthodox theological seminary for 5 years and studied portraiture in my free time. In my first year, God arranged for me to meet an important Romanian iconographer who, after the fall of communism, revived the authentic Byzantine legacy in Romania. I remember seeing one of his icons. I truly felt the presence of Christ right then and there. With joy and fascination, I finally discovered the icon.

After the Seminary, I studied sacred art at the University of Bucharest, within its Department of Theology. I learned all I could from my teachers and wonderful colleagues even though the situation there was far from ideal. To delve deeper on my own, I made copies of historical icons painted by the greatest iconographers.

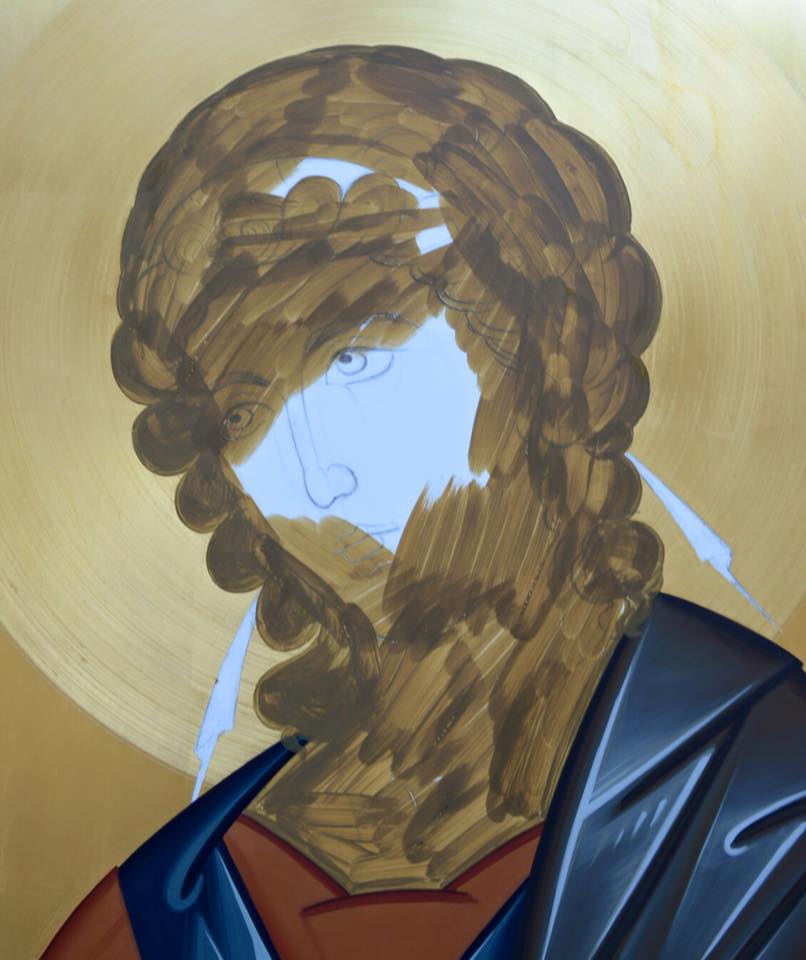

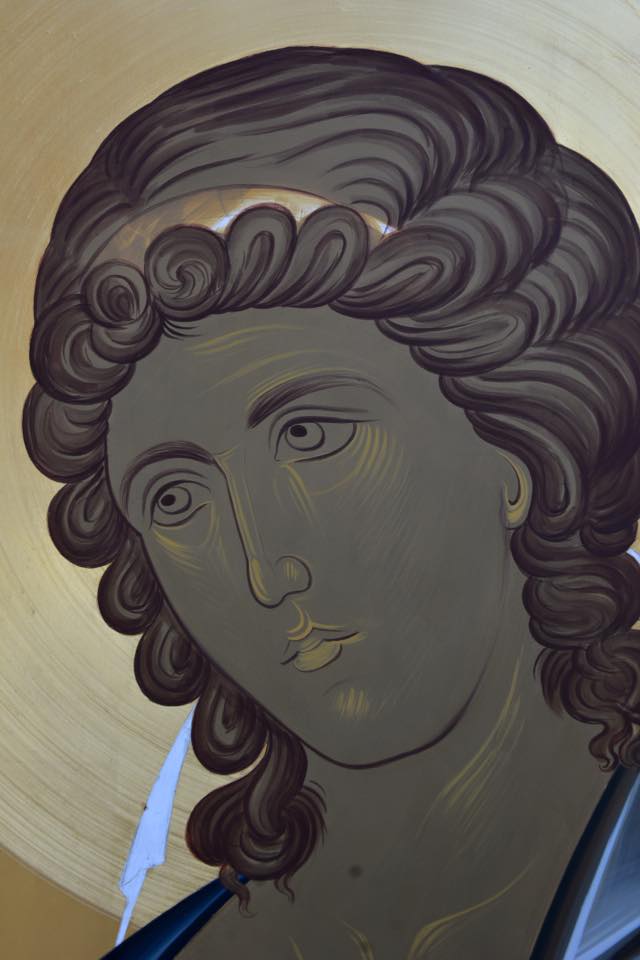

At the early beginnings everything was difficult. At some point I remember copying without any understanding what was there, looking for the internal logic. By the grace of the Holy Spirit, the one who inspired the ancient iconographers, I could slowly uncover one aspect of the icon at a time. I felt humble and knew I would always be a few steps behind these master iconographers. What is important though, is that we follow them.

During holidays, students could work with their teachers or other painters in egg tempera and fresco. Since most newly built Romanian churches are painted in fresco, after college many of us worked in this medium as part of a team. During the winter, all the work was done inside their ateliers, making icons for that church interior or other commissions. Some students spent more time as apprentices while others preferred their independence. I preferred a three-year apprenticeship with a fresco painter. It was a lot of hard work. In the beginning, I rarely touched a brush, but this was a way for me to learn to be humble.

A crucial step in my path was to stay on Mount Athos.

My goal was to understand historical icons and paint as our ancestral iconographers did. It was not easy; there were moments when it felt like I was on the edge of a cliff and would fall. Our temptations and responsibilities are great because the role of the icon in the salvation of mankind cannot be overlooked

Iconographers fly with two wings: good technique married to a healthy spiritual life within the church. The Holy Spirit helps if we fly in the right direction. God is the best teacher and arranges the right people to meet in the right places at the right time. I trusted Him to guide all my steps. I used everything that life offered to become a better iconographer.

Czarnecki – How do you recommend Americans study iconography?

Neculae –

The week-long workshops are really useful. Students can choose a teacher from any country in the world who best suits their needs. Workshops allow one to choose the style which is personally most resonant. In a condensed period of time, you can mine all the information and knowledge gained through their years of study and work.

An important aspect of a workshop is the possibility of meeting other students interested in icons, which is also helpful in terms of our spiritual and technical evolution. Working in a group setting confirms your level of experience; you benefit from critical and informed opinions of your work. Any student’s level of experience or age should have no bearing on their participation. As you can imagine, these criteria cannot be easily fulfilled by any educational institution. Working with only one or two students is ideal. But in a larger group, you learn from contact with your colleagues as well. If you can honestly admit you are not the best student in a group, your modesty will allow the Holy Spirit to work within you. Finally, the potential for the best improvements can begin.

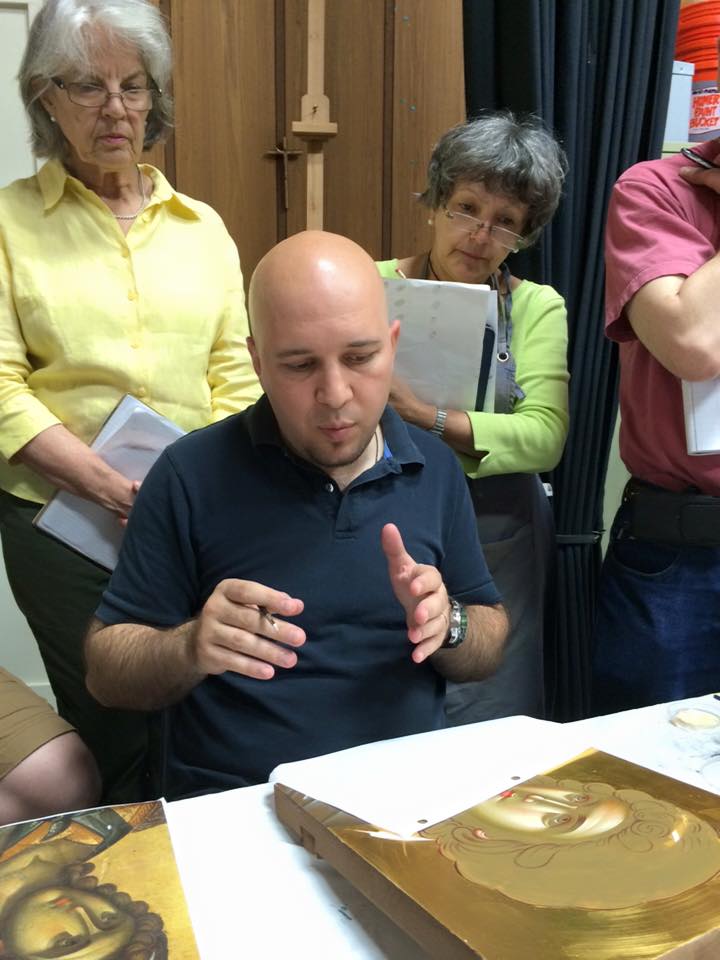

(Highlights video of Daniel’s 2015 workshop)

In addition to working with a teacher, students need to find inspiration in the most verdant periods of iconography within all regional traditions (Greek, Russian, Serbian, Romanian, Bulgarian etc.). I strongly recommend studying Byzantine iconography from its beginnings to the present, but focusing especially on the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. Pay attention to the old icons! Reproduce them as closely as possible. Use a clear reproduction of a historical icon which fascinates you. Copy it with precision, scrutinize all its details. Don’t be superficial!

I say this with urgency for all iconography students: be humble enough to learn from these master iconographers, whether they are famous or obscure. Don’t rush to be innovative or original! Let God decide when you are ready to do this. Petre Tutea, the Romanian Christian philosopher taught: “despise yourself constantly so that the void created in your heart may be filled by Christ.” In icons, we witness a true collaboration between man and the Holy Spirit. In order to receive all this iconographic inheritance, we must give ourselves up. God resists the proud, but gives grace to the humble.

The worst enemies an iconographer can have are pride, envy, ambition, superficiality and haste. Great artistic skill combined with pride will never create an authentic icon, but a person with great humility but with limited artistic skills may create miraculous icons. This may explain why there are so many wonder-working icons which aren’t perfectly executed, or have other shortcomings.

Czarnecki – There is a trend especially among contemporary Russian iconographers to work in a style that is earlier than the typically local schools- for example, Moscow iconographers working in 12th century Byzantine style. Do you see this same trend among the iconographers you know and work with?

Neculae – I don’t know if it’s a trend but there is a group of iconographers in Romania who are trying to innovate more.

Today, there are two kinds of iconographers in Romania.

One group follows an Athonite perspective and adheres to traditional, historical iconography. When it comes to innovating they are very, very careful. The other group feel they have enough knowledge of the traditional iconography and try to incorporate something new into the Byzantine canons. It is not my place to say whether either approach is good or bad; that is God’s work.

You find inspiration in icons from the first centuries to our days. May God give us the guidance to follow the best path for our salvation! At this point of my life I feel more attracted to the first category! I am most inspired from icons made between the XIIth and the XVIth centuries.

Czarnecki – Back to teaching, do you teach in Europe? The same way here, or do you take students on one at a time, or is there some routine to the lessons? Do you work alone or do you have help?

Neculae –

In Romania I had more time to train anyone who was eager to learn, with really good results. Some began drawing like children, but in time gained a very good understanding of Byzantine art. Now I have to be more selective accepting students and even dealing with clients. Students must convince me of their commitment. I make sure clients understand what they are buying.

I always had apprentices in my atelier, but at this point in my career I want full responsibility for my icons; I can’t let anyone else work on them. Maybe they can help with the preparation of the boards and even the gilding, but not the painting.

Czarnecki – What was it like for you to teach in the US? What was easy, what was problematic, what was a surprise?

Neculae – What convinced me to teach in the US was the enthusiasm for byzantine iconography, regardless of a student’s Christian denomination. In America, everyone was eager to learn and easy to communicate with. I saw on people’s faces a sort of holy joy. Painting an icon is more than just the act of painting, it is like a prayer, the same as when we are at Liturgy. It is a great gift from God but a great responsibility.

Daniel’s work can be seen on his website: http://www.danielneculae.com/