Similar Posts

Interviewed by Natalia Gorenok

Translated by Vladimir Morosan

The art of Church singing as an integral part of the life of the Church, like the Church itself [in Russia], is experiencing a period of revival. Along the way, there are still many difficulties, because many of the traditional practices among choirmasters and church singers were either lost or forgotten [during the Soviet period]. How has the situation changed over the past twenty years? How can one learn to sing with the heart, so that the church choir would become an open liturgical book for the congregation? We discuss these questions with Vladimir Gorbik—chief choirmaster of the Moscow Representation (Podvorye) of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, professor at the Moscow State Conservatory, and Rector of the Patriarch Tikhon Russian-American Music Institute.

To Sing with the Heart

NG: Vladimir, in preparing for this interview, I discovered that this year you are celebrating a milestone—the twentieth anniversary of your work as a church choirmaster.

VG: Yes, indeed, I have been at the Podvorye since November 1995. In August 1996, the rector of the Podvorye, now Vladyka [Metropolitan] Longin [1], blessed me to become the choirmaster of the monastic choir.

NG: One gets the feeling that you became fully captivated by this work, in which you continue to be involved to this very day. How did this happen?

VG: I would describe my becoming involved in directing a church choir as something of a miracle. If someone had told me twenty years ago that I would be a professional church choir director, I simply would not have believed it. Similarly, however, I would not have believed it if someone had told me that I would have ten children. Life is an unpredictable thing.

As for how this came to pass, I must mention, first of all, Vladyka Longin, because it is his energy and self-sacrifice and his desire to serve the Church that affected me very deeply. When I came to realize that at the Holy Trinity-Sergius Podvorye in Moscow men learn to save their souls in a manner similar to the way students at the Moscow Conservatory learn to be outstanding professional musicians, this process caught my attention.

I was and still remain basically a worldly person, though I try to live the life of the Church and to pray according to the measure of my abilities. Some people picture me as being virtually a monk, but this is not the case. I have a large family, and I am deeply integrated into the surrounding society, but I derive great satisfaction from the idea that I am helping the Church. I’ll tell you why.

One day Vladyka Longin said to me: “Volodya [a diminutive of Vladimir], I understand that you want to be a symphony conductor.” “Yes, I do,” I replied. He said: “Crowds of people line up and wait a long time for the opportunity to get up on a podium in front of a symphony orchestra, and they continue to compete in offering the best performances of classical works, which have long been performed numerous times by various world-class conductors. In the meantime, the Church is experiencing a dire lack of professional choirmasters.” For me, this was a turning point. His words caused me to recall the experience of Holy Archbishop Luke (Voyno-Yasenetsky) [known as the “Blessed Surgeon”]: just as his medical career was taking off, he suddenly decided to go to a village and simply treat sick people. This image still stands before me, and I get goose bumps from merely recalling the life experience of this saint. If it had not been for the personal, profound interest of Vladyka Longin and his desire to attract professionals to the work of the Church, I cannot even imagine where I would be today. I think my fate would have been pretty miserable. Generally, Vladyka Longin is a man who knows how to articulate the gist of things in a nutshell. He spoke the words—and lit a fire within me. And from there, a number of other people became enthused: my singers at the Podvorye, and now also my students and singers in America, in Australia, and so forth. The process continues, as they say. And I am very glad that this is happening.

The Male Choir of the Moscow Representation of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius in concert at the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory—recorded on the disc Today All Nations Beheld Glorious Things, May 11, 2010

NG: Perhaps the greatest event in the life of every Orthodox believer is the moment one comes to know God. While the second most important event, I would suggest, is becoming familiar with the world of monasticism. When you conducted the monastic choir, what did you learn from them, and what did they learn from you?

VG: As I said earlier, when I became involved with the Podvorye, I saw people who were learning how to save their souls and who approached this matter very seriously—studying of the Holy Fathers, participating in worship both as members of the congregation and as clergy, and so forth. This really captured my attention, particularly on a professional level, if one can put it that way. Despite the fact that deep in my family tree, going back from my great-grandfather, there were priests in every generation, this [realm of the Church and the spiritual life] was an area that was completely unknown to me in my childhood and adolescence. One of my grandfathers was an electrician, and the other, who was killed in World War II, was a simple peasant. My mom and dad were engineers. So when, thanks to Vladyka Longin’s efforts and through carrying out my duties at the Podvorye, I discovered the existence of such a world, this opened up great inner horizons for me.

As the director of the Brotherhood Choir, I participated in monastic tonsures, and attended the monastic evening devotions, during which the brothers read their prayer rules and akathists after All-Night Vigil had ended. I visited Mt. Athos twice. In general, I beheld and I continue to experience this hidden, inner world, and, I have to say, it is very captivating. Out of it develops a deep understanding—that a person is born and lives, first of all, in order to obtain salvation of his or her soul and, second, to influence others as much as circumstances permit, so that they, too, would ponder the meaning of life. This does not mean preaching salvation to anyone directly, but entails following the admonition of St. Seraphim of Sarov: “Save yourself, and thousands around you will be saved.”

With regard to professional skills, in the beginning monks typically do not know how to read music, but this can be learned, which they eventually do. And, taken together with the spiritual component, this brings about very good results. By the grace of God, after two years of my work with them, the choir began to sound like a professional choir, that is to say, [they began to sing] in tune. Oftentimes professional choirs sound as if they lack virility, “sterile, like a pharmacy”—as the saying goes. All the notes appear to be in place, but for some reason one has no desire to listen to them. Whereas in other cases, the singing is not only clean and in tune, but has soul. It is the monks who have the ability to sing in this manner. And by the way, our professional choir, seeing how the monks give it their all, and how they sing with their hearts, also get caught up in this process, and afterwards, making use of their professional skills, they end up following suit in the professional choir. So here we see a process that is profound, comprehensive, and very engaging. And, one might add, very professional, because the professional singers experience growth when they begin to sing with the heart, and, consequently, end up singing soulfully.

NG: In the mid-1990s the conditions [in the realm of church singing] were probably not like today, where we have a wealth of resources: back then there was a shortage of sheet music, of recordings, etc. How and from whom did you learn when you were first discovering the world of sacred music?

VG: Shortages of sheet music and recordings may have existed elsewhere, but not here, thanks to Vladyka Longin. I am absolutely convinced that here at the Podvorye, I received a third conservatory diploma [after graduating with Conservatory degrees in conducting and composition]. In addition, Bishop Longin introduced me to Father Matfey (Mormyl), whom I also consider to be my teacher. More than half of our library consists of sheet music from the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery [where Father Matfey was choir director]. Vladyka Longin had also brought back a lot of music from Bulgaria—for the most part Bulgarian ecclesiastical chants arranged by Petr Dinev. He had a huge library of both music and recordings. Sometimes I would spend several hours per day in Vladyka’s cell, where he would play recordings of church music and talk about his understanding of it, nourishing me both spiritually and musically. I can say with all assurance that the amount of knowledge about sacred music that I received from Vladyka Longin, and then later from Father Matfey—specifically as it pertains to the art of church singing—I certainly would not have obtained anywhere else. Of this I am totally certain.

As far as the present day is concerned, yes, it might appear that everything is as it should be. But at the same time, when you look around more closely, a feeling of sadness sets in. It seems to me that the art of church singing is nowadays moving in two opposite directions. The first direction involves the pursuit of purely musical achievements, together with self-promotion in all the four corners of the world, while forsaking the prayerful labor of singing in church. It’s the same as, when a person is satiated, he begins looking for extraordinary and special delicacies. By contrast, the second direction—that of sobriety and prayer—lies in developing, through practice, an understanding of what is true spiritual music. But the number of such choirs is incrementally smaller than the first kind. I’m not going to mention any names here: we have a professional code of ethics, just as in medicine, science, and any other form of art. We try not to discuss the activities of others in public, even if is it only to avoid criticizing anyone.

The Choir Must Be Like an Open Liturgical Book

A Male Chorus Master Class, comprised of singers from the U.S. and Canada, organized by PaTRAM (The Patriarch Tikhon Russian-American Music Institute). Jordanville, New York, February 2014

NG: One of your main creative vehicles at the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Podvorye is the men’s choir. What do you like about it? What are its particular strengths?

VG: I believe that the male choir offers the quintessence of prayerful singing, and not only in the Orthodox tradition. In the West as well, there are still well-known choirs that consist exclusively of men and boys. Today, I already have several “vehicles,” as you put it: a mixed choir, the choirs of boys and girls of the Choir School at our Podvorye, and the Patriarch Tikhon Mixed Choir in America. But here is why I like to work with the male choir at the Podvorye, and why I would never want to relinquish it: the male choir, speaking generally, is a special state of mind. It possesses a special kind of blend— both in the spiritual sense of the word, and in a musical sense. In fact, if one is going to sing “with one heart and one voice,” to quote the words of the Liturgy, this single focus, or more precisely, conciliarity, of hearts and souls is, in the end, what brings about a very high degree of musical and timbral blend.

When our Patriarch Tikhon Choir gave several concerts in America, I brought a recording back to Russia and played it for my colleague Jaroslav Filipsonov (who has made a number of outstanding male chorus arrangements for us, highly acclaimed by Professors Vladislav Agafonnikov and Roman Ledenev of the Moscow Conservatory Department of Composition). For me, the highest compliment was when he said: “Volodya, do you know what I like most about the sound of your mixed choir in America? It is the fact that they sound very similar to your male choir at the Podvorye.” What did he mean by this? — That, the women’s contingent of the Patriarch Tikhon Choir sang “with humility” in the deepest sense of that word. For it is with the female voices that one very often has problems for various reasons. After all, the whole phenomenon of a mixed-gender choir, in which the treble parts are performed by women, rather than by boys, is relatively recent, dating from only a little more than a hundred years ago in Russia. And one must have the ability to convince the women’s sections to sing so that certain individual voices do not sing louder than others, so that the sopranos do not overwhelm with their sound but sing with a bright, clear and beautiful tone—like a pale blue sky—and so forth. Thanks be to God, the American singers responded to these admonitions and sang as is customary in our Russian tradition.

When people ask me: “What makes your singing different from that of all the others?” I answer, “I do not know how it differs. But I can tell you to what [traditions] it is connected.” And here I am talking about two things. First of all—the tradition of the Moscow Synodal Choir. This comes from the [pre-1917] Synodal School of Church Singing through the Moscow Conservatory. Many professors of the Synodal School ended up teaching at the Moscow Conservatory and thus were able to transmit certain aspects of church-singing practice through the twentieth century. Among the most famous names are the composer-conductors Nikolai Danilin, Alexander Kastalsky, Pavel Chesnokov, and Alexander Nikolsky. To this lineup one can also add Alexander Sveshnikov. So, through the labors of these individuals, this tradition has been conveyed to the present day.

And the second tradition is the singing of the Choir of the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery under the direction of Archimandrite Matfey (Mormyl). This man came from four generations of church singers, which means he absorbed the practice of singing in a church choir with his mother’s milk, as the saying goes. In fact, he created his own school and approach to singing, which reflected both the tradition of the Synodal School and the monastic style. This second direction—that of monastery singing—is particularly crucial. If we may liken the singing of the Synodal Choir to the singing of ordinary secular people who have been taught to perform church music in a spiritually uplifted manner, in the case of Father Matfey, he directed singing performed by monks and seminarians, [which added a spiritual dimension]. Both of these branches become directly linked in the work of our Men’s Choir of the Moscow Representation of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery.

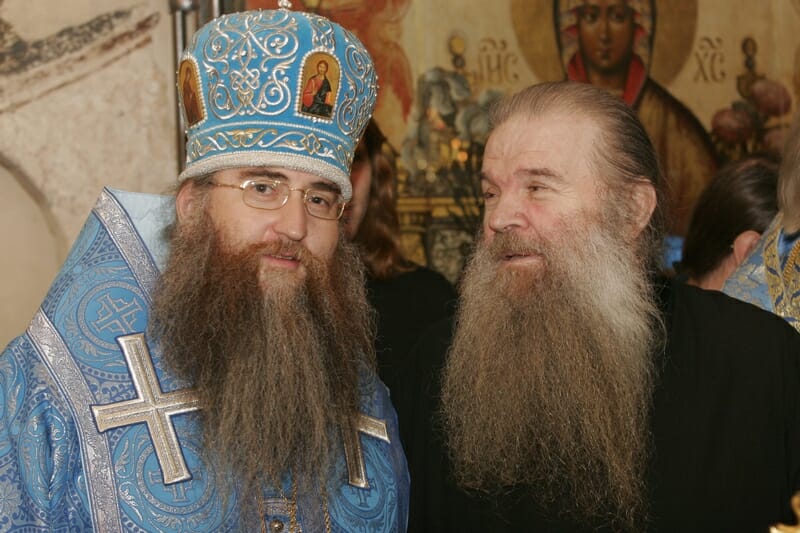

Bishop (now Metropolitan) Longin, of Saratov and Volsk and Archimandrite Matfey (Mormyl). Photo from 2005.

NG: How do you explain to your singers what you want to achieve? Do you first explain to them the spiritual meaning of a work, or set a creative task before them? How did Father Matfey go about this?

VG: Indeed, I try to do exactly as Father Matfey often did: he spent a lot of time talking about images that are at once spiritual and musical. It’s not as if I don’t talk about such technical things as tone, diction, and so forth, but one has to take a special approach, especially with people who may be hearing me for the first time, as in America, for instance. Following Father Matfey’s example, I devote a lot of attention to various images related to singing, I may cite some examples from everyday life, using what may be called the language of allegory. This is a language that is understandable to everyone.

This, of course, is something one spends an entire lifetime learning how to do. I started off with a chorus of monks at the Podvorye. These were, for the most part, common people. They did not understand what “dolce” (gently) meant in Italian, or what is a musical climax—the highest, most intense moment in a musical form. Or what is “staggered or chain breathing.” I had to explain all these things in the most simple of terms. These are some of the same things with which Father Matfey had to deal, so we had many similarities.

Once I asked him: “Father, how does one sing with proper vocal breathing? How do you understand a properly established singer’s breath?” (By the way, this was a conversation over the phone.) And here, this monk, an archimandrite of one of the most prestigious monasteries in the land, spent fifty minutes explaining to me how to sing, and he did this on more than one occasion.

He says: “Do you remember seeing a cow in a meadow?”

I was taken aback: here I am sitting at home, surrounded by walls, furniture, computer monitors, children, and all of a sudden—a cow in a meadow! I said, “Give me a moment, Father, let me recall a cow in a meadow. I saw one about twenty years ago… OK, I remember, and now what?”

“Do you remember how there’s something moving at her rear end before she says ‘moo’?”

I had to think back a while longer, and then replied: “Something in the region of her spine, if I recall, right?”

“Yes, there are two triangles there.”

And even though I could not see him at that moment, I could feel as if he was showing me with his hands exactly where these two triangles began to expand and widen.

“And so,” he says,” while taking in a breath with the full depth of its lungs, the cow expands them in volume, and then lets out a ‘moo’ that’s heard for miles around. Do you agree?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Well, there you are—an example of how the singer should properly take a breath.”

Thus, you see, the language of allegory and examples from everyday life is very helpful. It is much simpler and more understandable than using professional terms, because we live our lives in the midst of these very images. It’s a different matter that sometimes one has difficulty connecting stories from everyday life to the meaning and content of a given liturgical hymn. But in such cases God comes to one’s aid. I never prepare what to say in advance, but at the moment when I have to explain something, clarity comes into my heart, telling me what I have to say.

NG: How do you work on variable (proper) hymns?

VG: In the Orthodox Church, worship is impossible without variable [proper] hymns. It is the variable hymns—troparions, stichera, prokeimena—that constitute the essence of worship, which is why the Typikon or ordo of the Church is unique and complex. To be sure, we address God in the fixed, unchanging hymns as well, but the very essence of each service is to be found in the variable hymns.

Naturally, I explain the texts. Let us take, as an example, the preparation for the Matins of Great and Holy Friday. This service contains many stichera, which are very beautiful, but it would be impossible to sing this service prayerfully without explaining to the choir singers in the most basic terms what the texts mean. Unfortunately, not everyone is able to understand the Church Slavonic language in the same way I learned it at the Podvorye. But, nevertheless, we are all learning, and people are drawn to knowledge. In the midst of the rehearsal, we take a little break: I say: “This is what is being sung here. Look at the text, read it carefully. Still unclear? Then let me explain to you.”

A service at the Moscow Representation of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery with the participation of American singers who took part in the master class, organized by the Patriarch TIkhon Russian-American Music Institute (PaTRAM). July 2015

NG: It can be very disconcerting when the singing of a church choir seems decent enough, but one cannot understand the words of the changeable hymns such as stichera. Is there some secret solution to this?

VG: Once Vladyka Longin told me: “Volodya, a while back I invited a visitor—Eugene Tugarinov [2], a former teacher at the Moscow Conservatory. He came to one of our services and said to me: ‘Your singing is very good, but I could not understand a single word.’” And this is from a man with great experience in directing church choirs. Vladyka said: “Something must be done so that the words are clearly understood.” I then spent a few years (years!) studying this question—how to make sure that the words are clearly audible.

So, in answer to your question, I will share with you a small portion of this science. One must learn to project consonants (not vowels, but consonants) through all the obstacles (lips, teeth) that are involved in forming them, and once you do that, the consonant sound will clearly manifest itself. Generally, the better the resonance in the church, the worse it is for the parishioners. That is, the acoustics may be good for singing in general, for the vowels, but this destroys the consonants. The choir loves it: the singers let out just a little bit of volume, and the sound soars on its own accord. But to the congregation the words become incomprehensible. This is why I always teach my singers to “punch through” the resonant acoustics, so to speak, by exaggerating their consonants. As a result, one begins to hear good diction, and the people who are standing in the church are no longer merely listening to musical sounds, but for them the choir becomes like an open liturgical book, which they are able to read. I simply do not understand how one can come to a service and not understand what the choir is singing. This, in my opinion, is just horrible.

NG: In one of your interviews you cited Father Matfey’s words: “One must sing the service in such a way so as not to be ashamed before God and the saints.” This undoubtedly implies great concentration, yet people by nature tend to become distracted. How do you strive to preserve a focused attention, your own, and that of your choir?

VG: If one constantly focuses only on Father Matfey’s saying, while, at the same time, the tension in the choir keeps rising, it is useful to recall St. Anthony the Great’s example of a bowstring: if you just continually pull it tighter, it will eventually snap. [To prevent this from happening], the saint would occasionally amuse his spiritual children, so that they would also have joy in their hearts. In the choir there needs to be a balance between discipline on the one hand, and on the other hand, rejoicing in the fact that we are assembled together, singing to God, and that it is well with us. I strive by various means, using good humor when appropriate, to cheer the singers up and to carefully preserve a cheerful spirit in their hearts. Because, if one succumbs to either one of these extremes, the choir will sing poorly. There needs to be a middle ground, a good balance of discipline. And first and foremost, of course, the discipline must be applied to oneself. It does not matter whether one is standing in the choir at church or at home, praying before the icons. When my children are praying at home, and someone is standing there with their arms folded on their chest or propping their cheek up on an elbow, I always admonish them: “In the army, when one is in the honor guard, you stand at attention for hours, guarding the flag, but here you can’t stand up straight for ten or fifteen minutes before the icons…” Only when you stand consciously before God, being watchful over your feelings and thoughts, can you think properly about the content of the words. This is just a start. And then, once the words have become situated in your mind, and their meaning has become clear, only then—over time, not immediately—will the prayer move to the level of the emotions and the heart. St. Theophan the Recluse teaches us to repeat slowly and carefully, and many times throughout the day, the text of the prayers that we read in the morning and evening, so that the prayer becomes heartfelt.

So, back to your question—one must set oneself consciously before God, thinking about the content of the words, trying to throw off all extraneous thoughts and feelings—of which there are certainly a lot! This, of course, is the task of a lifetime. I cannot say today that I have achieved something in this regard. On the contrary, if I were to say that, it would be very foolish. But we need to move in this direction.

NG: We can hear this balance between an inner sobriety and an inner joyousness, can’t we?

VG: Of course, it is expressed in sound. I would say that when singing possesses meaningful substance and has the proper balance between restraint and joy, this manifests itself in the appropriate sound.

Students of the Choral School at the Moscow Podvorye of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra singing at a service

“Praise the Lord …”

NG: These days there are several choirs at the Moscow Podvorye of the Holy Trinity-Sergius Monastery…

VG: About ten.

NG: This seems to be quite a unique situation. How did it come to pass?

VG: Yes, this is indeed a unique situation. I think there is nothing quite like this, and not only in Russia, but elsewhere in the world as well. When Americans find out how many choirs we have, they say: “Volodya, please give us the charter of your Podvorye, of your choir school, anything that would help us establish something similar.”

This all began back in the days of Vladyka Longin, when our Sunday School achieved great success. It was a kind of foundational system for all those groups that now sing in worship services, both individually and as part of the composite mixed choir of the Podvorye.

Let me simply list our choirs: the men’s professional choir, the monastic brotherhood choir, the men’s amateur choir, the women’s amateur choir, the children’s choir of the Sunday school (from five years of age and up—the little ones), a boys’ choir and a girls’ choir of the Choir School, and a mixed youth choir. The amateur choir alone has three contingents: a preparatory group, to which parishioners come whenever they can and sing together, without the strict attendance policy as in the other choirs; and two others, which are directly under my direction, whose members are my students in voice and ear training, harmony, polyphony, conducting technique, and church choir leadership. My student Michael Shoshin also leads a choral class for two groups of the amateur choir—one group of, shall we say, medium ability and another group of higher achievers. The group of high achievers is integrated into our professional choir and even takes part in Patriarchal services and public concerts.

When we first started all this, I had before me as an example my alma mater, the Moscow Conservatory, where choral singing is very well represented. Plus the experience of Father Matfey at the Holy Trinity Monastery, where there are also many choirs: a choir of seminarians, a choir of the Choir Directors’ School, and a mixed amateur choir that also includes professionals—a fairly extensive network. Taken together, our combined choirs at the Podvorye number up to eighty singers. At our concerts of sacred music, we often present all the different choirs one by one, performing their individual programs, after which they all come on stage and sing one or two numbers together under my direction, demonstrating that we are able not only to sing separately, but also as a group. The image is one of little brooks, larger streams, and then—a big river.

NG: And they all sing at divine services?

VG: Yes. The parishioners like this very much, and they are glad that they have such an opportunity. But we have the strictest, I would say, army-like discipline in the choirs conducted directly by me and my assistants Michael Shoshin and Daria Dovgan. Only in the preparatory group of amateur men singers, which is led by my student Andrei Istomin, are people allowed to come whenever they can, as I mentioned earlier.

NG: You have mentioned your Russian-American project and the Patriarch Tikhon Choir several times. How and why were these groups established?

VG: This happened in September of 2013, in the following fashion. A gentleman from the United States, the servant of God Alexis Lukianov, came to Moscow with a proposition: “Volodya, I have an idea for you,” he said. “In our country Orthodoxy is divided into seemingly isolated islands, and I would really like to bring people together somehow [in the area of church singing].” Up until that time, I had already been to America and Canada several times and had occasion to speak about the work of our Podvorye in the realm of church singing. And then it happened that the Lord sent Alex to me—a person who not only has the faith and the mind to serve God, but also had the financial means to do something, since he was a successful businessman. Thus, he became the co-founder and Chairman of the Board of the Patriarch Tikhon Russian-American Musical Institute (PaTRAM) and a singer in the Patriarch Tikhon Choir. Incidentally, he has a wonderful voice—a basso profundo with a very low range.

The essence of our project is that we offer distance learning via Skype to choir directors in choral leadership, conducting technique, ear training, and vocal technique —all the subjects that are necessary for the professional training of any church choirmaster. Initially, our goal was to improve the situation with regard to church singing and choir directing on the North American continent. But now the Institute is doing its work virtually over the entire globe, because the situation with professional church choir directors is disastrous both outside of Russia, and in Russia itself, in its more remote corners. After a course of individual training, they gather in groups, and either I come to America, or they come here, so that we can engage in live, face-to-face communication. For example, in July of 2015, my first master-class at the Podvorye under the auspices of this Institute took place, which was attended by thirty-five Americans. And afterwards, we again begin working on the fundamentals [with a new contingent of students].

In September 2013, the Patriarch Tikhon Choir was launched, which performed three amazing and memorable concerts (judging from the reactions of both audiences and New York Times reviewer) in New York, Pittsburgh and Washington, DC. The singers learned their parts in advance, sent me recordings via the Internet to review, while others I reviewed via Skype. Then we came together and prepared the program in two days. Listeners were delighted and rewarded us with standing ovations, demanding five encores in New York, and they would have called for more, if I had not asked to let us go, because the choir was tired. Then, after another period of training activity, the choir reassembled in December 2014 to record a CD, Praise the Lord, All Ye Nations, which came out a year later, in late 2015.

Now we are preparing another major project: in early July, three choirs will come together in Saratov—an American men’s choir, our choir from the Podvorye and the Archdiocesan Choir of the Saratov Cathedral. Our goal will be to record a CD of Pavel Chesnokov’s works. Altogether there will be between forty and forty-five singers—a sizeable men’s choir.

Let me return to our Russian-American Institute. As Alex Lukianov was presenting his thoughts about this project to me, I was already having certain thoughts of my own, along the following lines—right now in the world there’s a very strong smell of gunpowder. Politicians are moving in opposing directions, and the situation seems to be the harbinger of some major catastrophe, possibly a war. And I, as the father of many children, am thinking to myself—I have to do something, recalling Christ’s words, “Where two or three are gathered together in My Name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matthew 18, 20). And this is indeed what has come to pass—we have people from different nations, from all corners of the earth, assembling and praising God together.

=================

[1] Hieromonk Longin (Korchagin) was appointed rector of the Moscow Representation (Podvorye) of the Holy Trinity-Sergius Lavra in December 1992. His labor began with the renewal of liturgical and monastic life at the Podvorye and the return and restoration of the churches and other monastery buildings. To learn more about this, see: “Kazhdyi razorennyi khram byl moei bol’yu” [Each ruined temple was my pain] (http://www.eparhia-saratov.ru/Articles/kazhdyjj-razorennyjj-khram-byl-moejj-bolyu)

[2] Eugene Tugarinov (b. 1958). A 1982 graduate of the Moscow Conservatory, he worked with amateur and professional church choirs in Moscow, London, and Amsterdam. From 1992 to 2001, he was a member of the Choir Directing Faculty at the St. Tikhon Orthodox University of the Humanities. From 1993 to 2000 – a teacher of conducting on the choral faculty of the Moscow Conservatory. Since 2001, the choirmaster of the Russian Orthodox Cathedral Choir in London. Now he is the chief choirmaster of the Epiphany Cathedral (Yelokhovsky Sobor) in Moscow.

Pravoslavie i sovremennost, Journal of the Saratov Diocese, Russia № 37 (53)

A truly dedicated churchmen and force of nature in Church music is the conductor Vladimir Gorbik. Certain aspects of church singing only became clearer when the choral lens of church music I inherited was cleared of its obscurities under his direction. Nothing compares with studying the sources by those who who continue an unbroken chain of sacred tradition—and one masterfully executed at that.