Similar Posts

Occasionally Jonathan Pageau and I like to experiment with our work – to skirt the boundaries of historical precedent, to revive forgotten and archaic techniques, or to juxtapose ideas in new ways. This project, an elaborate mixed-media icon of Archangel Gabriel, is such an instance. It was not a commissioned project, but rather something we decided to begin to see where it went, to find out which aesthetic paths it might lead us down.

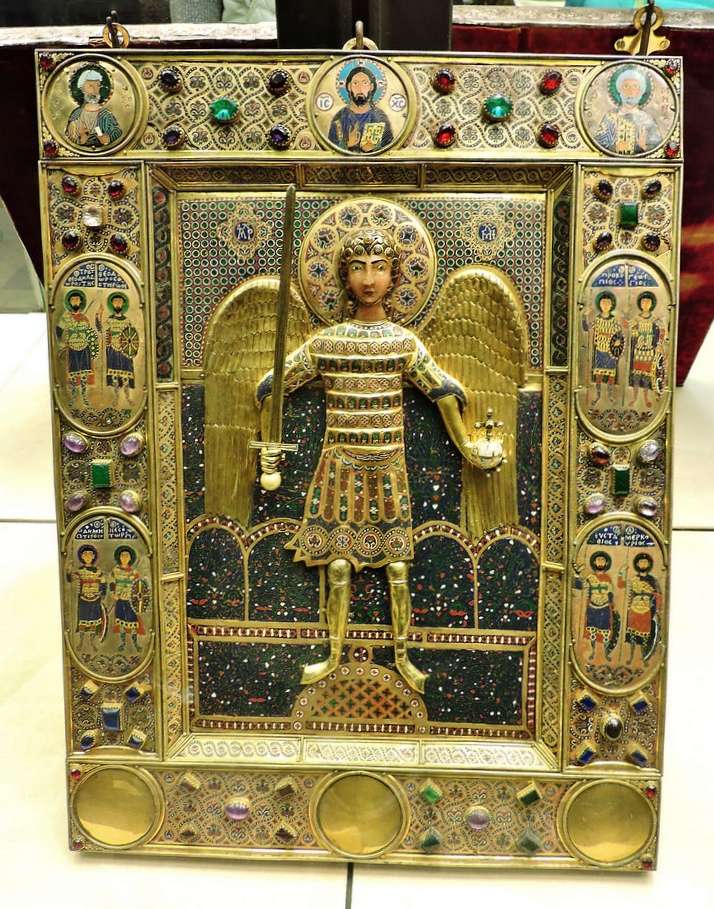

We chose St. Gabriel as our subject for several reasons. With his elaborate vestments, attributes, and wings, his icon has unique complexities. And as an archangel, it is traditional that his image would be rendered especially richly, as he is a direct representative of the splendor of God. There are the famous gold and enamel icons of Archangel Michael in the treasury of St. Mark’s, Venice, for instance, and we decided to conceive an icon of St. Gabriel that would likewise push the boundaries of material and craftsmanship.

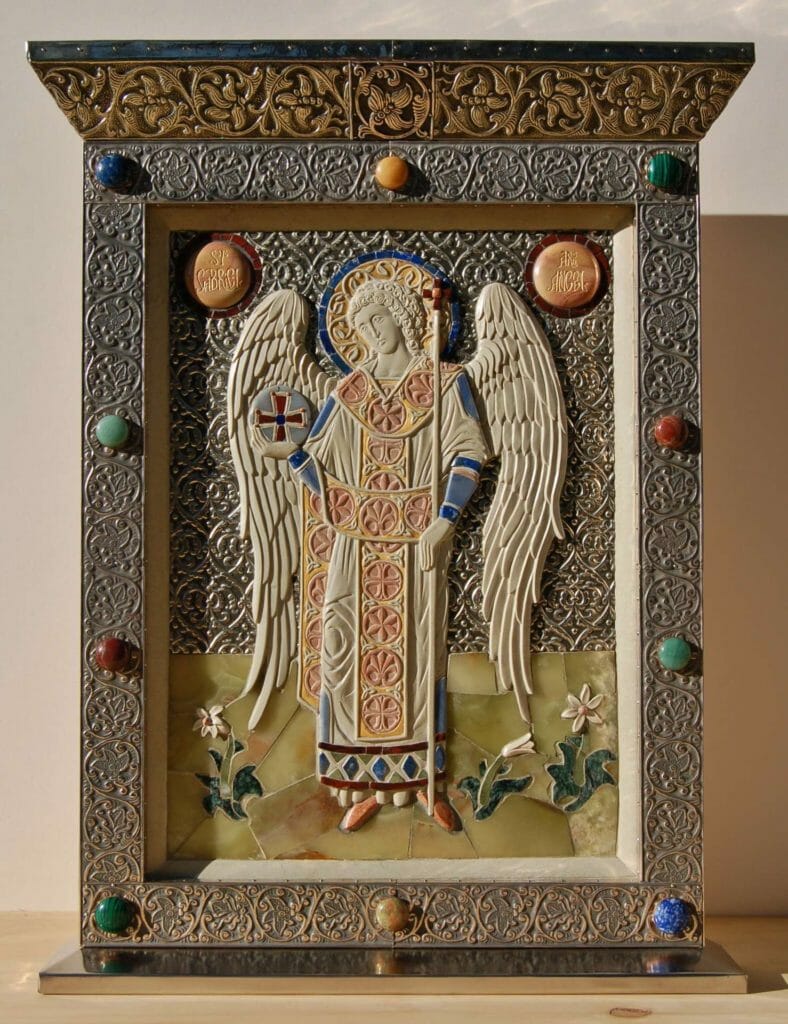

Jonathan based his carving upon a 12th-century Byzantine steatite with gilded details. But while this carving was carved from a single white stone, we decided to add color by means of inlaying other stones into the carving. This technique, known as opus sectile in ancient times, was never used together with relief carving, so far as we can see from surviving examples. (See article about opus sectile work here). However, carved images were sometimes painted, so use of multi-colored stones certainly seems compatible with iconographic tradition in that sense.

Jonathan created the icon from a single slab of white Kenyan steatite. He carved out the areas to receive the other stones – pink steatite, lapis lazuli, blue quartzite, red jasper, green onyx, and jade. These were ultimately epoxied into place and grouted. He then gilded certain details, and also the entire background.

When I received the carving from Jonathan, I felt that it was not entirely successful. Both the gilding and the inlaid lapidary details seemed in some ways to detract from the carving rather than support it. It was immediately clear to me that the problem with the inlaid details was one of scale. They did not have enough detail compared to the finely carved drapery and face. So I proceeded to refine those details, inlaying additional elements at the orb and cross, at the flowers, and elsewhere, making sure that each ‘focal point’ of the composition had detail worthy of attracting attention.

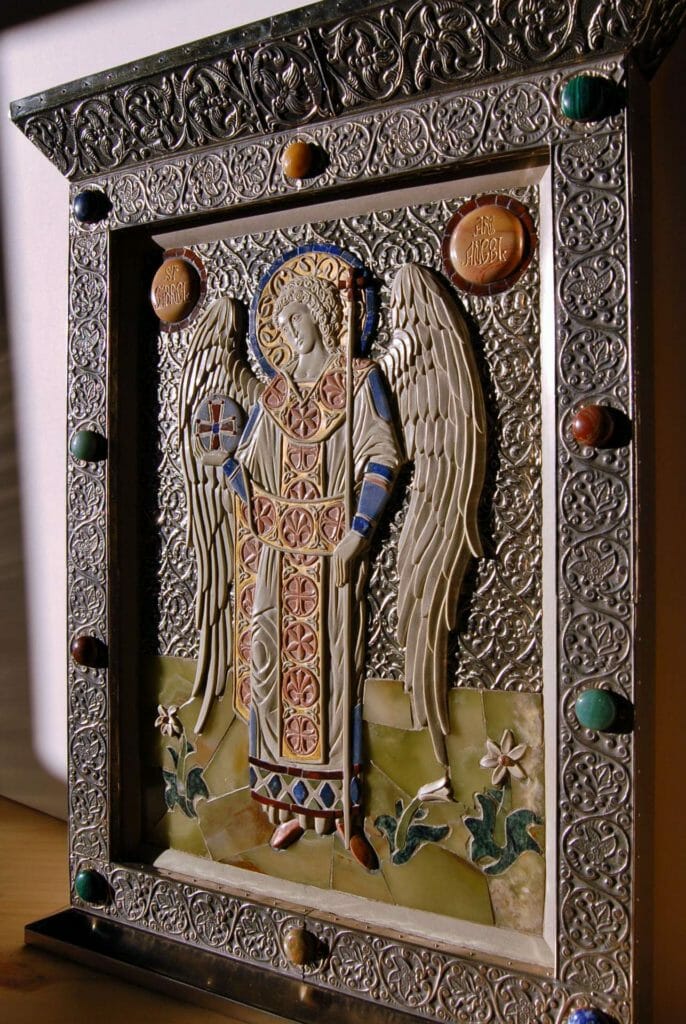

The gilded background was a bit of a quandary. Gilding is, of course, immensely flattering on a painted icon. But I realized that on a carved icon, a gilded background works to optical cross-purposes with the carving. The carving looks good only when the light is raking across the image, casting shadows. But the background looks good only when the light is face-on, lighting up the gold. Thus they are ever in tension, and there is no lighting condition in which the icon looks right.

So we decided to remove the most of the gold, and considered what to replace it with. Fortuitously, I had recently been to Moscow and had brought back some samples of basma – the embossed metal strips with which russian icons are sometimes clad. This proved to be the perfect material for both the background and the frame of our stone icon. It combines the optical qualities of both carving and gilding – it reflects the light like a gilded background, but it does so even when the light is at a raking angle.

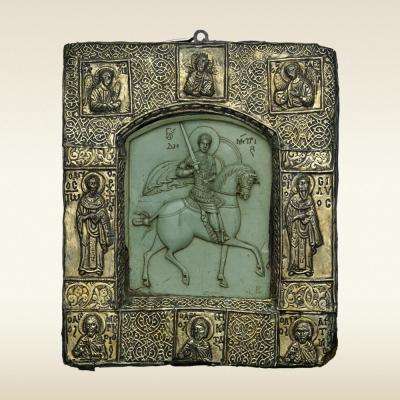

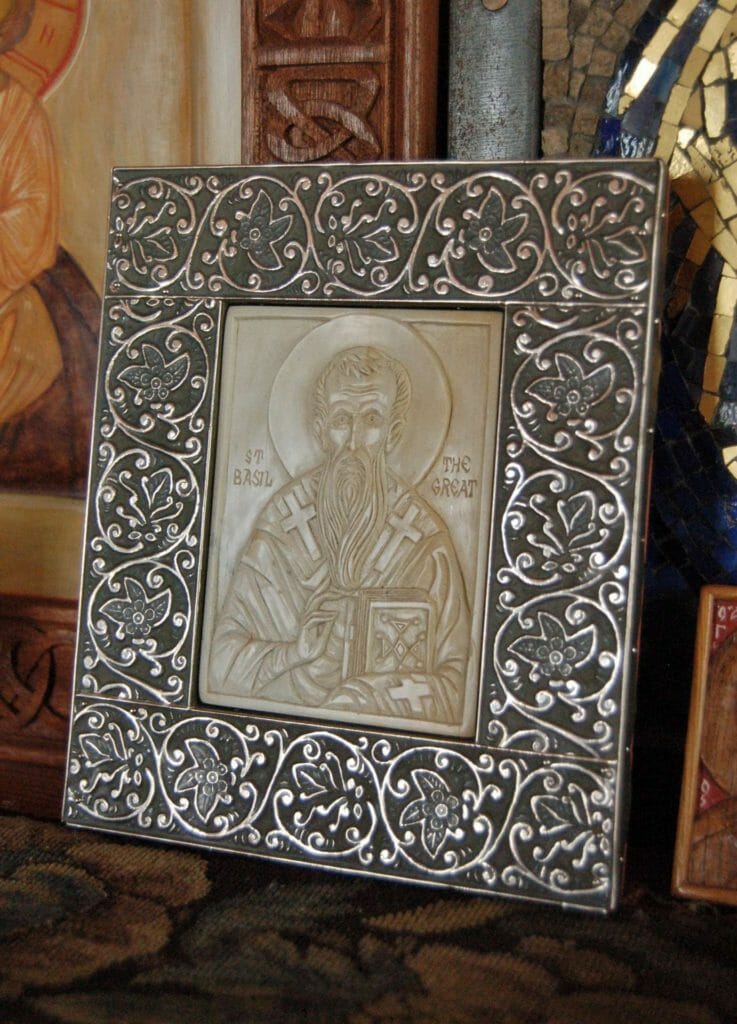

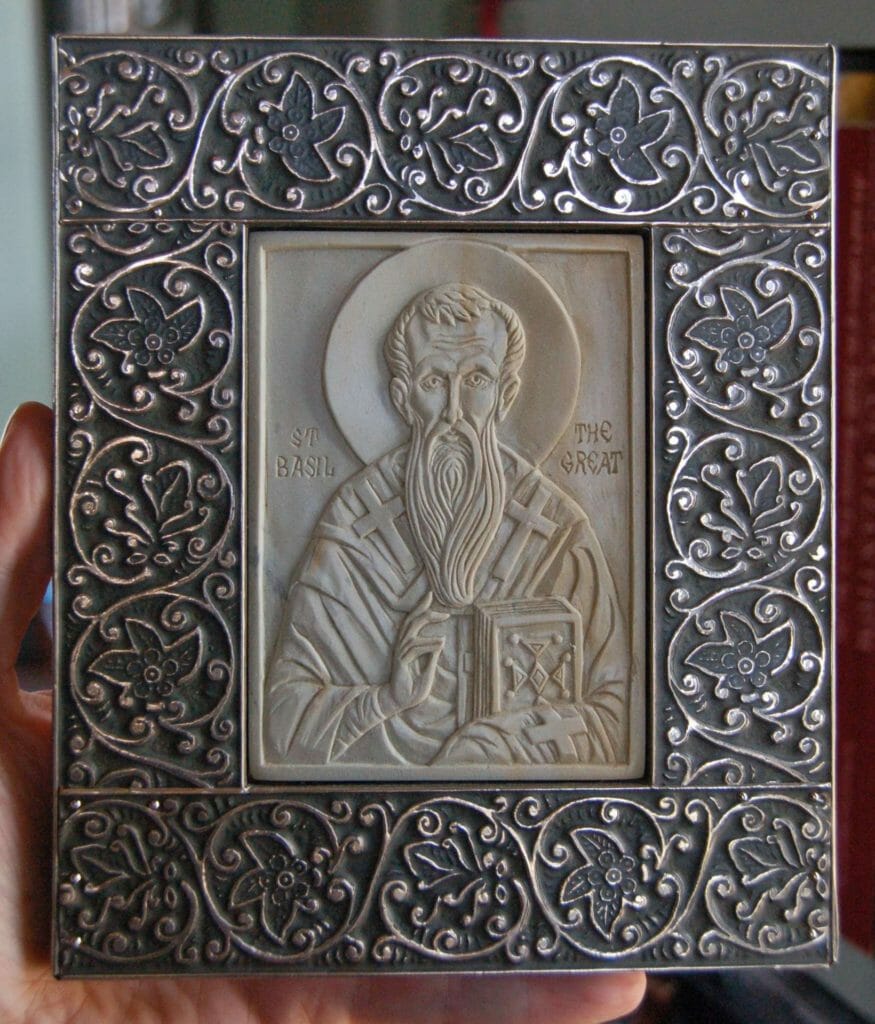

In retrospect, it should have occurred to us far sooner that embossed metal was ideal for framing Jonathan’s carvings. After all, many of the surviving steatite icons of the Byzantine era are framed in exactly that way – overlaid with embossed silver foil.

Before tackling St. Gabriel, I tried framing some of Jonathan’s smaller carvings with basma, and found the result more than satisfying.

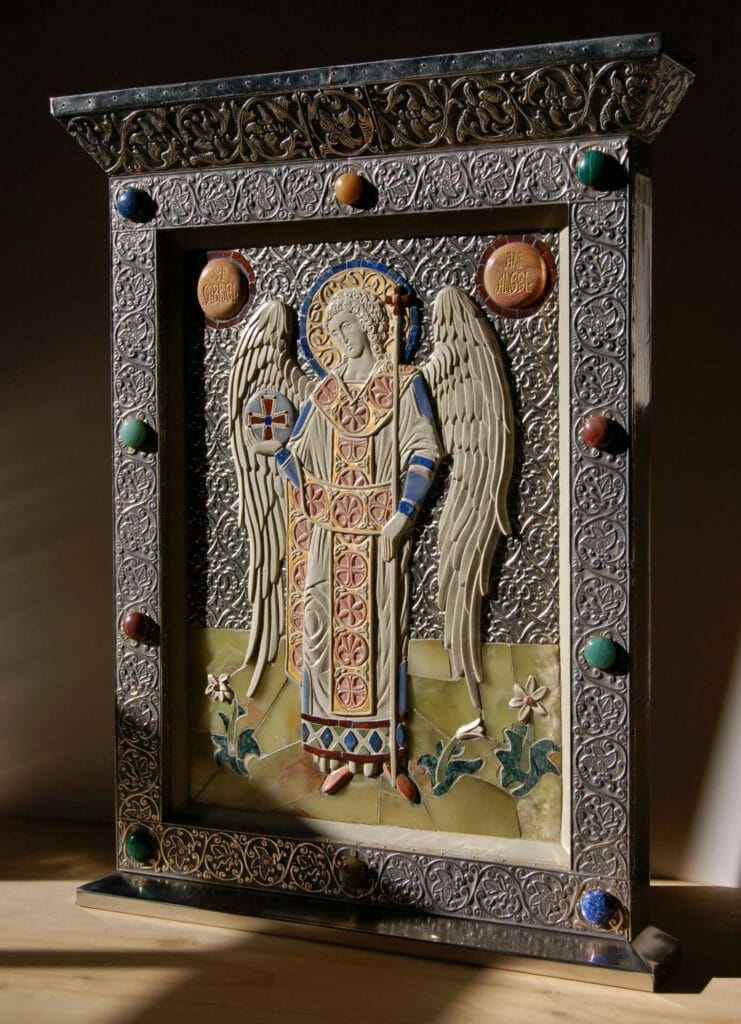

In completing the St. Gabriel icon, I used basma obtained from two Moscow workshops – Basm-Art (Maxim Lavdansky) and Artel Novo-Simonovskaya. It is made of nickel-silver. I applied the basma to the stone background using epoxy, and to the wooden frame using the traditional nails. I further ornamented the frame with cabochon gemstones in settings soldered to the basma – lapis, malachite, unakite, jasper, and green and yellow aventurine. The total size of the frame is 16 x 20 inches.

The finished work is a successful experiment. The several materials complement and support one another, adding richness without compromising clarity. In the right lighting, the icon has moments of remarkable scintillating richness, yet the face of the archangel always remains central and unobscured. I look forward to pursuing these techniques further in future projects, and am currently working to design my own patterns for basma, and to find better ways to integrate gemstones with the other materials.

This icon is breathtaking. Congratulations on creating a most beautiful work of art, worthy of spiritual contemplation for generations to come.

Maravilhoso. Muito lindo! Parabéns l

This was an amazing project and the final product is astonishing. The face is wonderful – very subtle work. The frame and the background are perfect. I have a couple of comments. It was a huge undertaking and the first, I hope of many of these. In my opinion, the changes to the folds on the lower part of the tunic – especially below the knee – were not successful. Also, I think the ornament on the stoles would have been better if it was a little flatter, more engraved like a fabric or embroidery. I think this is true of the flowers in the ‘grass’, too. These Byzantine flowers are notoriously difficult to get right in modern iconography.

I love the Byzantine work — and it is so sad that that contemporary patronage/art is at a place where a) this was NOT commissioned, and b) such a collaboration was an experiment, not something that you regularly do or is regularly required. Well done, thank you for your work.

Really wonderful. Thanks for the pictures of the process !

Great work! I’m glad you’re experimenting with basma. It complements the carving very well. I’ve seen basma used very effectively by some contemporary iconographers in Russia, but it seems to be a terrain unexplored in the U.S. So I’m pleased to see that you’re serving as a bridge to bring the technique here. I would love to see how you inmplement it on painted icons. Thanks for sharing the wonderful record of the process.

Fr. Silouan

Great work Jonathan and Andrew. The basma is a great success. It offers enough detail to create a worthy setting for the Archangel without being so fancy that it draws attention away from him.