Similar Posts

Editor’s Note: This article is a revised and expanded version of the talk with the same title given at the symposium, Living Tradition: Painting Sacred Icons in the 21st Century, organized by the Orthodox Arts Journal and which took place on May 23, 2015, at Holy Ascension Orthodox Church, Mt. Pleasant, SC. This post is the first of a series.

First Day of Creation, by Michael Wohlgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, from

the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicles.

…Each one of us has his own peculiar way of expression…The capable artist is by no means a mechanical copier, but a creator in the true sense of the term. Unfortunately, even among iconographers there are some who have the idea that…iconography is an art of copying. Such artists, by saying this reveal quite clearly that they have understood nothing with regard to this art, and that they are incapable of probing its mystical depth, but occupy themselves only with the surface.

– Photis Kontoglou, The Orthodox Tradition of Iconography[i]

Icons are a requirement of our nature. Can our nature do without an image? Can we call to mind an absent person without representing or imagining him to ourselves? Has not God Himself given us the capacity of representation and imagination? Icons are the Church’s answer to a crying necessity of our nature.

– St. John of Kronstadt, My Life in Christ[ii]

It has become axiomatic in most texts articulating the differences between the traditional icon and secular art to stress that icon painting has nothing to do with the painter’s imagination. The inordinate importance placed on the latter, as embodied in the works of post-Renaissance religious art, along with the erosive effects of secularism, are generally acknowledged as some of the main culprits behind the gradual estrangement and eventual forgetting of the traditional understanding of the icon within Orthodoxy since the 17th century.[iii] Moreover, the discipline of icon painting as a sacred art is often contrasted to the modernist notion of “self-expression,” since what is to guide the hand and determine the composition is not the painter’s ego, but rather the Holy Spirit and Tradition. The painter is to supply only his skill, his craftsmanship. He must get out of the way.

Thus “style,” the individual’s manner of expression, appears to be of no ultimate consequence. What matters is what is being said, the revealed doctrine, rather than who says it. Therefore, icon painting as exemplary of the “traditional doctrine of art,” can be described, in the words of the preeminent scholar of Medieval and Oriental art, A. K. Coomaraswamy, as a “constant and normal” art, whereas post-Renaissance art can be seen as “variable and individualistic,” modernist painting being one of the culminating examples of this tendency.[iv] In other words, if for in the former, stylistic variation hardly if at all changes, since its pictorial form has been acknowledged as best suited in embodying theological truth and manifesting the Sacred; for the latter, on the other hand, stylistic change is inevitable and encouraged, treated as an exhibitionism of solipsistic exploration and pursued in the name of “originality,” a must in keeping up with the zeitgeist. In short, our contemporary fixation on “style” is a mistaking of the accidental for the essential and betrays our culture’s preference for the contingent over immutable principles.[v]

This assessment is generally undeniable and has contributed to rid us of many prejudices held against the icon and other forms of sacred art. We often find parallels in the writings of the pioneers of the of 20th century icon revival: Photis Kontoglou (1895-1965), Leonid Ouspensky (1902-1987) and Pavel Florensky (1882-1937).[vi] Yet, there are some nuances that have been overlooked and need some reconsideration, if we are to avoid ideological oversimplification. I’m afraid that in an attempt to thwart the corrosive influences of Modernism we have at times distorted the understanding of the iconographic creative act. It could be said that in this way of viewing things, if we are not cautious, the icon painter can become solely a passive agent, lacking creative participation in his task, an unthinking tool, nothing more. Craftsmanship then truly becomes merely a “servile” act.[vii] So in an attempt to cautiously guard Tradition we are left with a stifling fear of innovation, the notion that icon painting is nothing more than the mechanical reproduction of old formulas. It then begins to resemble modern industry, in which the de-humanizing “anonymity” of the worker considered as a mere numerical “unit,” a cog in the production belt machine, replaces the transformative and qualitative anonymity of the traditional craftsman.[viii]

In what follows I will be looking at some aspects of these areas which have suffered from oversimplification and mischaracterization, mainly the roles that imagination and expression play in the creative act of icon painting and how these should not be shunned as contradictory to Tradition. This will contribute to dispel the misconception that authentic iconography mainly consists of duplicating a monolithic “Byzantine style,” a notion that contradicts how varieties of styles have always existed within Tradition as a manifestation of “unity in diversity” inspired by the Holy Spirit. This will in turn help us gather a better understanding of what is meant when we call icon painting a witness to living Tradition.

Ambiguous Imagination

In the context of Orthodox spirituality we often encounter calls for caution and watchfulness against the enticements of the imagination, the subtle, slippery and murky realm through which the demons, who use it as a playground, exert their psychic influence by inflaming the passions.[ix] This negative diagnosis is commonplace in ascetic writings on pure prayer, as can be found in the classic text on Orthodox hesychastic spirituality, The Philokalia. It is therefore quite natural to find the use of the imagination also discouraged in texts dealing with iconography. However, St. John of Kronstadt, as can be seen in the passage quoted above, appears to run counter to the norm. While, on the one hand, the ascetic tradition speaks of the imagination as detrimental and deceptive, on the other hand, St. John sees it as a gift from God. So is there a contradiction here?

No, not at all. St. John does not contradict the ascetic tradition, but rather augments and complements it, thereby helping us arrive at a more nuanced and complete understanding. He is definitely not to be interpreted as encouraging the cultivation of imaginative fantasies, which lead to delusion, as a method of prayer. Rather, he gives us the other side of the coin.[x] Instead of focusing on the dangers surrounding the misuse of the imagination, he points out its indispensable, edifying and profitable side – its undeniable link to the icon. The two are inseparable; the one presupposes the other, since the imagination involves nothing other than mental images, that is, mental icons. To deprecate one is to deprecate the other. Therefore, he finds in the imagination a defense for the icon. But St. John is not alone. He in fact echoes St. Theodore the Studite who says:

Imagination is one of the powers of the soul. It is itself a kind of image, as both are depictions. The image, therefore, that resembles the imagination cannot be useless…If imagination were useless, it would be an utterly futile part of human nature. But then the other powers of the soul would also be useless: the senses, memory, intellect [nous], and reason. Thus a reasoned and sober consideration of human nature shows how nonsensical it is to despise the image and the imagination.[xi]

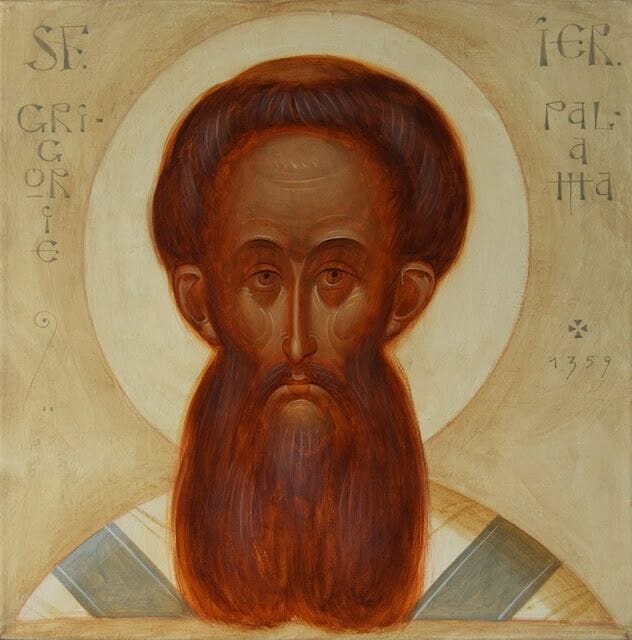

Likewise, St. Gregory Palamas, in Homily 26, does not hesitate to acknowledge the imagination as a God given and positive faculty, an inherent part of our consubstantial human nature. Thus in describing man’s excellence as microcosm, the “summing up” of “all Creation in one creature,” he points at how the visible and invisible worlds, the sensible and noetic, are indescribably bound together in him partly through the imaginative faculty.

God made man in a mysterious way, gathering together, so to speak, summing up all Creation in one small creature. That is why he was last to be created, belonging to both the visible and invisible worlds and adorning them both. In man God united mind and senses in an indescribable manner, using imagination, judgement and reason to bind them truly together… Man and the world are both the work of the same Craftsman, and have much in common, but whereas the world is larger in size, man is more excellently constructed.[xii]

Thus a different kind of imagination begins to emerge, quite different from the one we’re used to hearing about. Not only does it play a crucial role in binding together man’s microcosmic constitution, but according to St. Gregory it also serves a mediatory role in the acquisition of knowledge. As Fr. Demetrios Harper notes, in the Natural Chapters, “…Palamas divides the parts of the human power-triad into noetic, rational, and sensory capacities, (62-3) defining the various kinds of knowledge of which the human being is capable. The intellect [nous] is ultimately involved in the attainment of the three forms of knowledge, interfacing with senses and the sensory world through mankind’s φανταστικόν[xiii], or faculty of imagination.”[xiv] Hence, “Despite the frequency with which thought-images are described as dangerous by ascetic literature, including Palamas himself, it is evident that St. Gregory considers the imagination to have a κατά φύσιν [according to nature] function.”[xv] In other words, the faculty of imagination is an integral part of our nature, not just a superfluous post-lapsarian anomaly. A distinction must be drawn between the faculty itself and its impure, impassioned use, dangerous “thought-images” and other symptoms of its state of illness. As with other aspects of our soul, such as the insensive and desiring aspects, it is to be purified and used not contrary, but rather according to nature, in a dispassionate manner, guided by the illumined nous.

It then becomes clear that we should be cautious not to cast the imagination away as completely useless and evil, based on our misunderstandings and misapplication of hesychastic texts. Our conception of it cannot be solely defined in light of its illness and misuse, as described in the latter. Indeed, we are not to cultivate fantasies during prayer, but, as briefly shown, the imagination is more than fantasy or illusory allurements. So what I want to focus on is not the complexities surrounding methods of prayer, but rather on how, as a God given faculty, the imagination can be used properly and play a profitable role in other areas, in particular, craftsmanship.

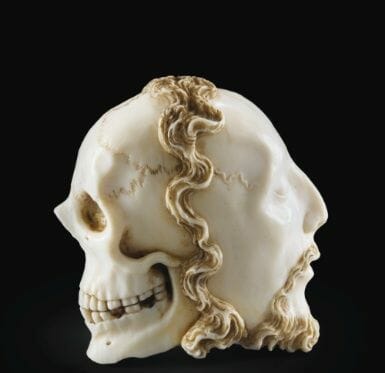

Page from the sketchbook of the medieval craftsman Villard de Honnecourt. Dating about c. 1225-1235.

We can then say that the imagination, as a receptacle of images and sensations, is a neutral faculty of the soul, closely related to memory. It is “more refined than sense perception, but more coarse” than the nous, man’s highest faculty. [xvi] As an intermediary region, an “isthmus,” bordering between the senses and the nous, it serves a mediating function which makes it ambiguous; like Janus, the deity of transitions, being neither here nor there, as if having two faces.[xvii] It can look up, towards the intelligible light of divine Truth, and thereby become luminous; or it can look down, towards the enticements of the senses in hedonism, and become darkened.[xviii] In its receptivity to impressions it resembles soft and pliable wax.[xix] It can also be compared to a mirror. So what is it reflecting? How is it being impressed, inscribed and directed? In what direction is it looking? It can be steered by the purified nous, inspired by the Holy Spirit, or by the passions, manipulated by demons. Therefore, “As Palamas affirms…in the Natural Chapters, the thoughts formed through the φανταστικόν [imagination] can be either used for the cultivation of virtue or vice, depending on the way in which they are used.”[xx] In short, in its neutrality the imagination can either lead us to delusion or aid us in our ascent towards deification.[xxi]

***

But this clarification brings us to yet another ambiguity pertaining the term imagination. The word immediately conjures up many associations and implications, based on contemporary presuppositions about art, which run contrary to the traditional practice of icon painting. This further complicates matters, especially since most discussions about the icon tend to center around its doctrinal import, its theology, rather than on the complexities of its creative act. Consequently it often goes unnoticed, bypassed or ignored, that the latter inevitably involves imagination and expression, inextricable aspects of traditional craftsmanship. A fact that also touches on the general confusion that exists surrounding the term “art.”

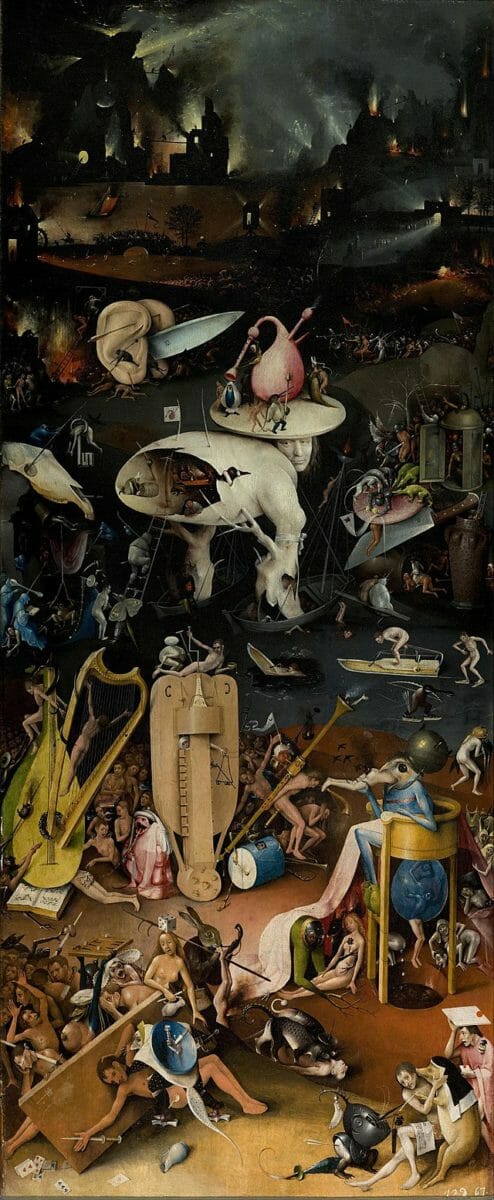

The Garden of Earthly Delights (detail), by Hieronymus Bosch, 1490-1510.

Oil on oak panels, 87 in × 153 in. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

This, I’m sure, sounds dangerous to those of us who have been repeatedly told that the icon is not to be confused with “art.” Which amounts to saying that it has nothing to do with the pursuit of dubious creativity, vain self-expression and reckless fantasy, works of “irrational impulses that yearn for innovation.” For some this is perhaps best exemplified by the Gothic nightmares of Hieronymus Bosch and the kind of religious painting that deforms the sacred into the voluptuous and extravagant. But then again, some might recall with apprehension the elevation of irrationality under the banner of the imagination, above stifling and deadening reason, in Romanticism; others of its connection to the lugubrious subconscious in Surrealism; and still others will blame it for all the aberrations we see today in contemporary galleries and museums. But, needless to say, when it comes to the creative act, this is not the “imagination” we have in mind.

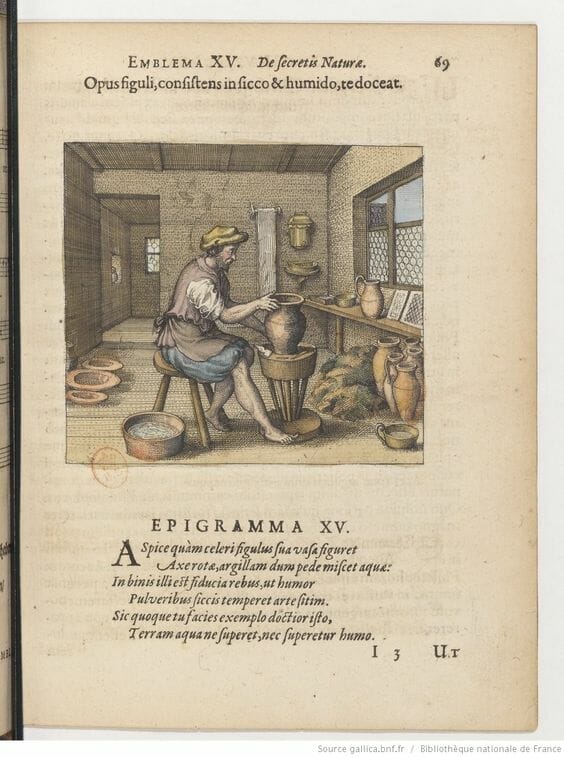

Rather, when we speak of the imagination, or the imaginative act, we mean the mental imaging process that precedes any making or manufacturing.[xxii] We articulate within ourselves an idea or form as a mental image before we ex-press, that is, create the work and bring it to actuality.[xxiii] Thus the imagination in this sense serves as an aid in problem solving. Using Aristotle’s “four causes”[xxiv] terminology, we can call the idea the formal cause in contrast to the final cause, that is, the end or purpose towards which the work is directed; the craftsman himself and his tools, through which the work is realized, being the efficient cause; the raw material to be shaped by the imagined idea, the material cause.[xxv] This hylemorphic formula can be abbreviated to its two main poles, formal (eidos) and material (hyle), which were pretty much taken for granted in medieval thought surrounding the work of art. [xxvi] Therefore, there is no question that in this traditional understanding of craftsmanship, the imaginative act, as the conception of the idea (eidos)[xxvii] in solving artistic problems, plays a crucial and inevitable role, hence the need for us to understand its implications, valuable and positive connection to iconography.

Potter at work shaping formless matter according to his imagined idea.

Engraving by Michael Maier in the Atalanta Fugiens, 1618. Emblem XV.

But, it should be stressed, that what the iconographer imagines or “recalls to mind,” as St. John puts it, are not his own illusory inventions, but rather revealed Truth, real deified persons and sacred events, as noetically known within the mystery of ecclesial life. In other words, the content of his formal cause is not his own, but rather the resplendence of Orthodox Tradition. The imagination is to be purified, directed towards the light of these divine archetypes, in order to clearly reflect them as on a polished and luminous bronze mirror. In this way his use of the imagination will in no wise be running contrary to the Acts of the Seventh Ecumenical Council held in Nicaea in 787, which reads: “The making of icons is not an innovation of painters but [it is] a tradition of the Church…It is a notion and tradition of the Fathers and not of the painter. The art alone is the painter’s.”[xxviii]

This statement is usually referred to when emphasizing that the painting of icons did not arise from and therefore is not to rely on “innovation”, that is, inventions of the imagination. However, implicit in this extract we find a distinction being made between the negative and efficacious use of the imagination. The first corresponds to private “innovation,” the painter’s invention of images divorced from and running contrary to the consensus of the Church; whereas the second is contained in the acknowledgement of the painter’s art, his craftsmanship, that by which the patristic Tradition is symbolically embodied.[xxix] But, as we have alluded to and will elaborate further on, this dependence on Tradition does not mean that the act of craftsmanship is merely “servile.” Rather, it presupposes the free contemplative act of “re-imagining” the prototypes to be re-presented, which allows for pictorial interpretation according to temperament. This brings us to the question of expression.

As just mentioned, the imagination is to function as a polished bronze mirror. However, no two mirrors are the same, inevitably the reflection of each, depending on polish, nuances of surface quality and luminosity, will have peculiar characteristics. Hence, from the positive use of the imagination just described arises what Photis Kontoglou calls a “peculiar way of expression,” an indispensable feature of the authentic icon as an embodiment of living Tradition. I believe that looking at this often overlooked side of the creative act can help us avoid the approach that makes of iconography mere slavish repetition, the superficial and mechanical copying of old works and nothing more, arising from fear of “artistic license,” and often accompanied by a simplistic notion of what it means to adhere to Tradition. Indeed, this superficial approach, which can be described as “academic conservatism,” will always be encountered as a stumbling block to avoid in the practice of any traditional sacred art. How then are we to overcome this tendency?

The alternative I would propose is an approach to icon painting that reclaims the positive use of the imagination, in which the prototype is engaged not merely as an external sketch, but also internally, as a mental image to contemplate noetically, with the eye of the heart, and interpreted in the painting process. The highest ideal in the application of this approach is to be seen in the iconographer who does not rely on external sketches at all but works directly from his heart. It seems clear to me that the diversity of styles in the history of icon painting attests to this act of re-imagining throughout the centuries, in which personal and cultural temperaments are not stifled but rather flourish in freedom, as they express the ecclesiastical experience of the incarnate Logos in unique ways, yet in full harmony and conformity to Tradition.

To be continued….

[i] Photis Kontoglou, “The Orthodox Tradition of Iconography,” in Fine Arts and Tradition: A Presentation of Kontoglou’s Teaching, C. Cavarnos (ed.), The Institute for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, Belmont, 2004, pp. 63;66.

[ii] S. John of Kronstadt, My Life in Christ, E. E. Goulaeff (trans.), Cassell and Comp. Ltd., London, p.430.

[iii] On the imagination and its detrimental influence in icon painting see: L. Ouspensky, “Art in the Russian Church During the Symodal Period,” in: Theology of the Icon, Vol. II, A. Gythiel (trans.), SVS Press, Crestwood, 1992, pp. 435-436; idem, “The Icon in the Modern World,” ibid., pp. 473-474; P. Kontoglou, op. cit., p.30; P. Evdokimov, “The Canons and Creative Liberty,” in The Art of the Icon: A Theology of Beauty, Oakwood Publications, Redondo Beach, 1996, p.216; M. Quenot, The Icon: Window on the Kingdom, SVS Press, Crestwood, 1991, p. 66-79; P. Florensky, Iconostasis, SVS Press, Crestwood, 1996, pp.78-82; C. Cavarnos, Guide to Byzantine Iconography, Vol. II, Holy Transfiguration Monastery, Boston, 2001, p. 145; A. Louth, “Tradition and the Icon,” in: The Way, 44/4, October, 2005, p. 149; I. Yazykova, Hidden and Triumphant: The Underground Struggle to Save Russian Iconography, Paraclete Press, Brewster, 2010, p. 143.

[iv] A. K. Coomaraswamy, On the Traditional Doctrine of Art, Golgonooza Press, Ipswich, 1977, p. 5.

[v] As Coomaraswamy puts it, “Styles are the accident and by no means the essence of art…” A. K. Coomaraswamy, Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. 1972, p. 39.

[vi] We are greatly indebted to these men and they should be honored for their monumental work in bringing about a change within the Church, from the predominance of naturalistic religious painting, to a rediscovery of the theological significance of the traditional icon. Yet unfortunately, the stark either/or rhetorical tone used in their polemics in defense of the icon have often been misinterpreted. Whatever they have said which serves to balance their exaggerated statements has for the most part gone unnoticed, leading to the dissemination of many misconceptions. Hence, some regard their mystagogical hermeneutic as faulty since, in their opinion, it “dogmatized” the icon’s traditional “style,” or “painting mode,” something that had never been done before. Moreover, it is felt that this has led to the notion that the icon’s “style” is unalterable, which denies the historical fact that stylistic variation, vitality and freedom, has existed within the Tradition throughout the centuries. In this paper we aim to contribute towards a corrective to this problem of stylistic “dogmatism” without, however, claiming that the icon’s pictorial principles are void of doctrinal significance. Indeed, it is clear and undeniable that the variety of traditional “styles” that have existed, and continue to exist, all attest to the common goal of pictorially expressing Orthodox theology, of embodying the Church’s spiritual vision in “rendering” the Sacred. Those pictorial principles that have been acknowledged as effectively accomplishing this task and tie together all of the schools of icon painting within the Tradition is what we prefer to call the “traditional style,” rather than the “Byzantine style.” See: Dn. Evan Freeman: George Kordis Interview for the Sacred Arts Initiative. https://vimeo.com/190603732, 2016, (accessed 16 November 2016).

[vii] Speaking of the distinction to be made between the “free” and “servile” aspects of craftsmanship, Coomaraswamy notes: “The artist is given the commission and is expected to practice his art. It is by this art that he knows both what the thing should be like and how to impress this form upon the available material, so that it may be informed with what is actually alive in himself. His operation will be twofold, ‘free’ and ‘servile,’ theoretical and operative, inventive and imitative. It is in terms of the freely invented formal cause that we can best explain how the pattern of the thing to be made or arranged, this essay or this house, for example, is known.” A. K. Coomaraswamy, “Art, Man and Manufacture,” in: Our Emergent Civilization, R. N. Ashen (ed.), Harper and Brothers, NY, 1947, p.158-9.

[viii] On aspects of anonymity see: Todor Mitrovic, “Icon, Production, Perfection: Reconsidering the Influence of Collective Authorship Startegy on Contemporary Church Art,” in: International Journal for Philosophy and Theology, Vol. 14, 2014, pp. 337- 351; R. Guenon, “The Two-Fold Significance of Anonymity,” in: The Reign of Quantity & The Signs of the Times, Sopphia Perennis et Universalis, Ghent, 1995, pp. 78- 84.

[ix] On the negative aspects of the imagination, especially as it bears on the ascetical life and prayer see: Nicodemos of the Holy Mountain, “Guarding the Imagination,” in: Nicodemos of the Holy Mountain: A Handbook of Spiritual Counsel, Paulist Press, Mahwah, 1989, pp.146-152; Archimandrite Sophrony, “The Struggle with the Imagination,” in: The Undistorted Image: Staretz Silouan 1866-1938, R. Edmonds (trans.), The Faith Press, London, 1958, pp.85-96; Igumen Chariton of Valamo, The Art of Parayer: An Orthodox Anthology, E. Kadloubovsky and E. M. Palmer (transs.), T. Ware (ed.), Faber and Faber, London, 1997, pp. 24-25; Hieromonk Damascene Christensen, Father Saraphim (Rose): His life and Works, St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2003, p. 805.

[x] While hesychastic literature mainly treats prayer from an apophatic perspective, St. John is focusing on the cataphatic dimension, which involves the use of visual, written and verbal forms of symbolic representation. The two approaches are inseparable and complementary of each other, both in the domain of theological discourse and the overall liturgical life of the Church. Speaking of this complementary interaction, Bishop Kallistos notes: “In Scripture, in the liturgical texts, and in nature, we are presented with innumerable words, images and symbols of God; and we are taught to give full value to these words, images and symbols, dwelling upon them in our prayer. But, since these things can never express the entire truth about the living God, we are encouraged also to balance this affirmative or cataphatic prayer by apophatic prayer.” And speaking of hesychia, the way of stillness, he adds: “…The hesychast, as well as entering into the prayer of stillness, uses other forms of prayer as well, sharing in corporate liturgical worship, reading Scripture, receiving the sacraments. Apophatic prayer coexists with cataphatic, and each strengthens the other. The way of negation and the way of affirmation are not alternatives; they are complementary.” Bishop Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Way, SVS Press, Crestwood, 1995, pp. 121-22.

[xi] Epistolarum Liber, II.36 (PG 99 1213 CD); Both St. John of Kronstadt and St. Theodore the Studite echo Aristotle who says, “To the thinking soul images serve as if they were contents of perception and when it asserts or denies them to be good or bad it avoids or pursues them). That is why the soul never thinks without an image.” De Anima, 431a 15-16; Speaking of St. John of Damascus, A. Louth notes, “John’s approach also involves a positive attitude towards the imagination […] for it is the imagination that receives images in the human mind (Imag. I. II).This appreciation of the imagination remained part of iconophile theology.” A. Louth, St. John Damascene: Tradition and Originality in Byzantine Theology, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004, pp. 217-18; For a summary on the role imagination in Byzantine iconophile theology also see: G. Mathew, Byzantine Aesthetics, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, 1971, pp.115-119; Nicholas Constas, “Icons and the imagination,” in Logos, 1.1, 1997, pp. 114-27.

[xii] Homily 26. 1, in: The Homilies of St. Gregory Palamas, C. Veniamin (ed.), St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press, South Canaan, 2004, p.46. Similarly, St. Gregory also states, “Man brings his mind [nous] and senses into unity with the higher wisdom of someone mingling elements that cannot be mixed, by using his imagination, opinion and thought as noble bonds linking opposites together.” In the same homily he also echoes Aristotle’s notion of the imagination as “passive nous”: “Imagination has its starting point in the senses, but exercises its abilities even in the absence of objects which can be perceived by the senses. It could perhaps also be called mind [nous], in so far as it can act without such objects; however, it is subject to feelings, and is not indivisible.” Homily “On the Entry into the Holy of Holies II,” in: Mary The Mother of God: Sermons by Saint Gregory Palamas, C. Veniamin (ed.), Mount Thabor Publishing, South Canaan, 2005, pp. 44-46.

[xiii] The Greek word φανταστικόν, here translated as “imagination,” can also bear the connotation of “imaginary” and is also closely related to the term φαντασία, in Latin phantasia, from which the English word “fantasy” is derived. Hence the confusion that arises when speaking of “imagination,” in which these terms are conflated and used interchangeably, causing it to be collapsed into and mainly relegated to the category of the “illusory.” However, the Greek terms are more rich and subtle, encompassing a broad set of connotations such as: “appearance,” “presentation,” “perception,” “impression,” “image” and even “light.” Thus we can interpret φανταστικόν as a faculty having to do with φαντασία, that is, “appearances” or that which “presents itself” as a mental image, whether in the act of perception or afterwards, when this is once again recalled in the mind. As Aristotle puts it in De Anima, ‘phantasia is the faculty by virtue of which we say that an image presents itself to us” (De Anima, III, 3, 6). He also ads, “Phantasia has derived even its name from light (phaos) because without light one cannot see” (Ibid., 3, 14). So the question is whether what “presents itself” in our imagination has become distorted into an illusion/fantasy, or if it can serve as a vehicle for the acquisition of true knowledge. This, of course, requires the exercise of noetic discernment. In short, not all that appears imprinted on the imagination, or that is willingly manipulated by us in the development of ideas in craftsmanship, is to be treated as a morally reprehensible illusion/fantasy per se, although it is not ontologically in the same level as “concrete”, or rather, corporeal reality. On φανταστικόν and φαντασία see: Aristotle, De Anima, R. D. Hicks (trans.), CUP, Cambridge, 1907, p.193.

[xiv] Fr. Demetrios Harper, “The Exemplar of Consubstantiality: St. Gregory Palamas’ Hesychast as an Expression of a Microcosmic Approach to Personhood,” pp. 7- 8. A paper delivered at the international conference, Understanding Person: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Perspectives from the Christian East, held at the School of Theology, Aristotle University, in Greece, on 14, May, 2014.

https://www.academia.edu/27647263/The_Exemplar_of_Consubstantiality_

St._Gregory_Palamas_s_Hesychast_as_an_Expression_of_a_Microcosmic_

Approach_to_Personhood (accessed 21 November 2016).

[xvi] St. Nicodemos, op. cit. p. 146.

[xvii] Ibn ‘Arabī’s view of the imagination as “isthmus” (barzakh) parallels to some degree the patristic perspective. This is evident in particular in regards to the imagination’s ambiguity as an intermediary “barrier” between, “two integral domains, the ‘two seas,’ that are at once related and separated” by it, as explained by Samer Akkach. For the Fathers these domains are the noetic and sensible realms, whereas for Ibn Arabi it pertains to Being and non-Being. Akkach continues: “Just as the borderline between light and shadow, the barrier through its unitive-separative nature brings together the two neighboring domains [Being and non-being] into a productive relationship.” See: S. Akkach, Cosmology and Architecture in Premodern Islam: As Architectural Reading of Mystical Ideas, SUNY Press, Albany, 2005, pp. 41- 42; According to Proclus the imagination’s ambiguity, because of its middle position between higher and lower forms of knowledge, led Aristotle to refer to it erroneously as the “passive Nous,” but the latter should be considered as impassible; Proclus, A Commentary on the First Book of Euclid’s Elements, G. R. Morrow (trans.), Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1992, p. 41; Likewise, in Ambigua 10.11, St. Maximos the Confessor, seems to echo Aristotle when mentioning that the nous has both active and passive aspects. St. Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, Vol. I, N. Constas (trans.), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2014, p. 167.

[xviii] See: Stratford Caldecott, “Faith Reason and Imagination,” in: All Things Made New, 22 Sept. 2011. http://thechristianmysteries.blogspot.com/2011/09/faith-reason-and-imagination.html (accessed 21 November 2016).

[xix] Thus, in its malleability or plasticity, it can be seen as designating the passive principle (hyle), awaiting imprinting by the active principle (eidos). Therefore, if left unattended by the illumined nous, the egemonikon, as active principle which stabilizes it and “imprints” it from “above,” it becomes chaotic and darkened by impressions from “below.”

[xx] Fr. D. Harper, op. cit., p. 8.

[xxi] All of this presupposes the necessity of engagement in ascetic discipline and prayer, which leads to growth in discrimination. As Bishop Kallistos explains, “Growing in watchfulness and self-knowledge, the traveler upon the Way begins to acquire the power of discrimination or discernment (in Greek, diakrisis)… He learns the difference between the evil and the good, between the superfluous and meaningful, between the fantasies inspired by the devil and the images marked upon his creative imagination by celestial archetypes.” B. K. Ware, op. cit., p. 115.

[xxii] This fact of human making is unavoidable and undeniable. As Brian Keeble says, “What is in the imagination is the motivating raison d’être, is indeed the formal cause of every act of human making.” B. Keeble, “Notes on Art and Imagination.” in: Daily Bread: Art & Work in the Reign of Quantity, A. Frisardi (ed.), Angelico Press, Kettering, 2015, p. 16.

[xxiii] Speaking of the traditional and universal view of art A. K. Coomaraswamy explains: “The older view has been that the work of art is the demonstration of the invisible form that remains in the artist, whether human or divine…Imagination is the conception of the idea in an imitable form. Without a pattern (paradeigma, exemplar), indeed, nothing could be made except by mere chance.” A. K. Coomaraswamy, “Imitation, Expression, and Participation,” in: The Essential K. Coomaraswamy, Rama P. Coomaraswamy (ed.), World Wisdom, Inc., 2004, p.181; Cf. Exodus 25: 40; Hebrews 8: 5; St. John of Damascus, “First Apology,” 10, in: St. John of Damascus, On the Divine Images: Three Apologies Against Those Who Attack the Icons, David Anderson (trans.), SVS Press, Crestwood, 1980, pp. 19-20; Cf. Plato, Timaeus 29AB; Aristotle, Physics II.2.194a.20.

[xxiv] Physics II. 3; Metaphysics V. 2.

[xxv] “Art is the imposition of a Mental Image upon Material, by certain Means, for a given End.” John Howard Benson & Arthur Graham Carey, “The General Problem,” in: Every Man an Artist: Readings in the Traditional View of Art, Brian Keeble (ed.), World Wisdom, Inc., 2005, p. 108; C. Cavarnos notes: “Form (εἶδος, μορφή) and matter (ὕλη), basic notions in Aristotle’s Metaphysics and Physics, occur often in Patristic writings, not only in discussions of Nature, such as Basil’s Hexaemeron, but also in the treatment of ethical and even sacramental topics.” C. Cavarnos, “Basic Elements of Aristotle’s Philosophy in Patristic Orthodox Thought,” in: Orthodoxy and Philosophy: Lectures Delivered at St. Tickhon’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, Institute of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, Belmont, 2003, p.215; On the four-fold causality of a work of art in Byzantine thought, in particular as it relates to St. Nicephorus of Constantinople, see: G. Mathew, op. cit., pp.119-121; Also see: P. J. Alexander, The Patriarch Nicephorus of Constantinople: Ecclesiastical Policy and Image Worship in the Byzantine Empire, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1958, pp. 203-205.

[xxvi] For an overview of hylemorphism as it relates to craftsmanship see: Titus Burckhardt, Sacred Art in East and West: Its Principles and Methods, Lord Northbourne (trans.), Perennial Books LTD., Pates Manor, 1986, pp. 55-59.

[xxvii] On the definition of eidos as “coincident with idea” and the “‘art in the artist,’ to which he conforms his material,” see A. K. Coomaraswamy, “The Medieval Theory of Beauty,” in: Coomaraswamy Selected Papers Vol. 1, Traditional Art and Symbolism, R. Lipsey (ed.), Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1977, pp. 194-195.

[xxviii] Sacrorum Conciliorum Nova Et Amplissima Collectio, ed. By Mansi, 252BC; As cited in Sotiria Kordi, Byzantine Painting and Visual Communication, p.15.

http://www.academia.edu/1566573/Byzantine_Painting_and_Visual_

Communication (accessed 9 October 2017)

Thank you for doing this important and foundational work for the Church, Fr. Silouan. In my opinion the scarcity of comments in response simply underscores the incontrovertibility of thought presented. You’re like, *mic drop*.

Thanks for the feedback Baker. I’m glad you find the work helpful.

[…] This is part 2 of a series: Part 1 […]