Similar Posts

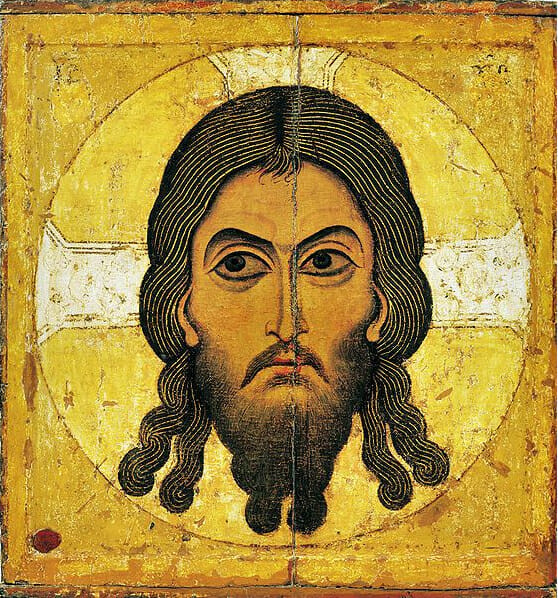

Acheiropoietos Icon (Not Made by Human Hands). Kiev, Russia, 12th century.

Conclusion: Towards Fullness of Iconicity

Perhaps the Acheiropoietos is the most lucid “mirror reflection” of the Logos and as such the ideal icon, the lucidity or “iconicity” toward which all icons aspire. In it we encounter the principle of “direct imprinting” of the image of the Person of the incarnate Logos by means of His uncreated glory. In this image “not made by human hands” some might see a kind of “photographic” or “mechanical reproduction.” However, paradoxically, in order for the icon to acquire lucidity of expression, it must inevitably involve personal involvement, “human hands,” artistic creativity and skill guided by the Holy Spirit, the transformation of the iconographer through his initiation into the life of the Church. Thereby the glory of the Logos then shines through and is manifested, being reflected, imprinted or embodied in matter through craftsmanship. In this divine-human craftsmanship can be seen an analogy to the Great Work of Art, the Incarnation itself. It goes without saying that this principle is lacking in the products of machine manufacture.

We can clarify the meaning of “iconicity” by comparing the icon to a mirror. The optimum level of iconicity of a mirror, which is its capacity to reflect an image the most clearly, takes place when its surface is seamless and cleanest. Any crack or build–up of dust will reduce visibility or blur the reflection, thereby degrading its iconicity. Likewise, the icon “reflects” the incarnational mystery most clearly when it avails itself of the methods and materials that have been tried and tested for centuries and handed down to us by tradition. In addition, lack or mastery of artistic skill plays a crucial factor. Both extremes can degrade iconicity. Lack of concern for traditional methods or command of basic formal principles can distort the prototype, mistaking disfiguring for transfiguration. Conversely, an overemphasis on artifice and academic repetition of old models can strip the icon of spirit or expressive power. The ideal balance resides in artistic mastery and creativity informed by spiritual vision. Optimum iconicity is not to be found in the superficial copying of ancient styles. This might be an initial stage, but this attitude undermines the continuation of the Holy Spirit in the life of the Church. At Pentecost, the apostles spoke in different tongues, attesting to the importance of diversity in unity. In tradition we can find the “multiplicity of tongues” of various styles. Even though we do not speak of willful individualism in icon painting, this does not mean that the unique personality of the painter or national temperament is erased by the tradition.The personality in fact flourishes in a unique mode of expression as it cooperates with the Spirit, thereby contributing to the edification and adornment of the body of Christ. In the history of the icon we find an organic development of the canon that is full of vitality. Its Hellenic artistic heritage is enriched and informed by other cultural forms of expression. The challenge is to internalize the prototype and express it with spiritual vision according to tradition, without denying our historical moment. This doesn’t happen without taking risks.59

The descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles at Pentecost.

Interior of a dome at the 9th-century Basilica of St. Mark, Venice.

12th century mosaic of gold, bronze and other precious materials

Some oppose classifying iconography as art since it should not be considered as art for art‘s sake. They rather prefer to call it a form of “writing.” This might apply to the icon figuratively as “theology in color,” venerating it as we do the Gospel. Nevertheless, it is a liturgical art, the aesthetic expression of Revelation that transcends arbitrary choices and the artist’s individualism. Iconography is not an end, but a means. It inclines us to prayer, leading to doxology, repentance, and the purification of the heart. The “art” of the portable icon we have been discussing is that of painting, with inherent principles of line, tone, form, plasticity, color, composition, and rhythm.60 From these have arisen a unique mode of anagogic expression that required centuries of arduous effort, in cooperation with the Holy Spirit and shaped by spiritual vision.61 Herein is found the timeless representational principles that unify all the local schools and historical periods of iconography.That is why we speak of icon painting rather than icon writing.62

There is diversity in unity among schools of icon painting, as can be seen in the various depictions of Pentecost shown above . One school can not claim monopoly of “true” interpretation of the Tradition. It is important to remember, and emphasize, that in icon painting local and personal temperaments are not obliterated, but flourish in adherence to its timeless pictorial principles.

Does a portable icon, through its symbolic language, fulfill its function according to tradition?63 Is it an effective mirror that clearly manifests the mystery to which it is linked? The theological and aesthetic dimensions of these questions have been considered above. Concern with the icon’s materiality is not to be confused with aestheticism,a desire to be moved or get lost merely on an emotional or phenomenal level.64 These are not matters of taste.65 Nevertheless, canonical aesthetic forms “move in order to convince,”66 uplifting us to see with the eyes of the heart. This involves a departure from the senses, passing through psychic effect into noetic vision.The material qualities of the icon and their meaning are essential to that dynamic, determining the degree of “iconicity”– how it shapes or “colours” us spiritually, as St. Peter of Damascus says.Reproductions lessen the icon‘s power since they distort its material symbolism. In the distortion of the symbol, iconicity is reduced.

Fullness of iconicity can be met when the canonical image and the properties of its medium embody the Tradition. Both are necessary and depend on each other. The tension between them must be maintained. The icon is an “energetico–material bearer,”67 manifesting the energies of both the prototype and the materials that embody it. Paradoxically, the ontological status of the icon is both transparent and opaque. It is transparent in that, like a glass, we look beyond its matter and encounter the prototype. It is opaque in that the energies of its material properties are unavoidable and essential, subtly affecting our ascent to spiritual vision. This is the fullness of the icon that reproductions simulate.

Insofar as a reproduction is matter imprinted with the prototype, it is an icon, albeit inferior. Its artificial materials manifest mass production, the endlessly repeatable uniformity of consumer products, and, in short, the desacralized world of machines. Lacking craftsmanship, it is deficient in conveying the sacramental role of matter and its liturgical dimension, which presupposes the cooperation of human and divine energies. Its material energy, in discord with that of the traditionally hand painted icon, degrades symbolic power (i.e., iconicity). The discerning heart, encountering an icon imprinted by artificial forms rather than the real thing, remains malnourished, spiritually unsatisfied, and hindered in its ascent towards Beauty.68

Some would like to think that “what defined the icon in Byzantium was neither medium nor style, but rather how the image was used and especially,what it was believed to be.”69 Many saints have prayed before reproductions. This does not make their prayers less authentic and acceptable to God, nor does their holiness make the reproduction more real or liturgically efficient. Reproductions remain surrogate icons, lacking iconicity. Then again, many miraculous and weeping icons happen to be reproductions, attesting to the fact that God is not confined. Neither subjective feeling, nor experience, nor miracles change the ontological status of the icon.

While icon reproductions have advantages,we should not forget their deficiency as liturgical objects. They distort the theology of the icon. Exceptions resulting from circumstance should not be taken as the norm. Better to have one hand painted icon than ten reproductions, to encourage icons produced by a hand guided by the Spirit rather than products of a spiritless machine – less is more. This involves a challenge for patrons and benefactors in the Church. The faithful may need to change their approach in how much they are willing to invest for the glory of God and what they should expect from the art of iconography. The challenge for the iconographer is to continue the advancement of the revival of icon painting, respecting and retaining the traditional methods not merely as a copyist, but as a creative artist of spiritual vision. Having said this,the goal is not to encourage a formalist mentality, but rather an awareness of these significant concerns. The more we ignore seemingly inconsequential compromises, the more we compromise the Tradition.

“Lord, I have loved the beauty of Thy house and the place where Thy glory dwells.”(Ps.26:8)

Notes:

59 A. Hart, Diversity Within Iconography”: An Artistic Pentecost, unpublished.

60 Coomaraswamynotes:“Art, from the Medieval point of view, was a kind of knowledge in accordance with which the artist imagined the form or design of the work to be done, and by which he reproduced this form in the required or available material. The product was not called “art,” but an“artifact,” a thing “made by art”; the art remains in the artist. Nor was there any distinction of “fine” from “applied”or “pure”from “decorative”art. All art was for “good use” and “adapted to condition.”Art could be applied either to noble or to common uses, but was no more or less art in the one case than the other.” A. Coomaraswamy, op. cit.,p.174.

61 Ibid.“The adequacy of the symbols being intrinsic, and not a matter of convention, the symbols correctly employed transmit from generation to generation a knowledge of cosmic analogies: as above so below. Some of us still repeat the prayer, Thy will be done on earth as in heaven.”Ibid., p.166.

62 Chrysostomos notes: “Eikonographia … refers not only to descriptive writing, but also to symbolism and symbolic illustration. Neither is the word solely associated with writing, nor is it correct to translate it as “writing of Icons” when it properly refers to iconographic illustration or painting. And finally, need we point out to the competent scholar of the Greek language that a zographos is not a writer, but is, of course, a painter.” (Archbishop Chrysostomos of Etna, Iconography and the Inner Life:Holy Icons and Spiritual Vision Reified, Orthodox Tradition, Vol. XXIX, Num. 1,p.6.

63 A. Coomaraswamy,op. cit., p.166.

64 Ibid. “The collector who owns a crucifix of the finest period and workmanship, and merely enjoys its “beauty,”is in a very different position from that of the equally sensitive worshiper, who also feels its power, and is actually moved to take up his own cross; only the latter can be said to have understood the work in its entirety, only the former can be called a fetishist.”Ibid., pp.167–68.

65 Ibid. “Medieval…men whose view of art was quite a different one, men who held that “Art has to do with cognition” and apart from knowledge amounts to nothing, men who could say that “the educated understand the rationale of art, the uneducated knowing only what they like,” men for whom art was not an end, but a means to present ends of use and enjoyment and to the final end of beatitude equated with the vision of God whose essence is the cause of beauty in all things.This must not be misunderstood to mean that Medieval art was “unfelt”orshould not evoke an emotion, especially of that sort that we speak of as admiration or wonder. On the contrary, it was the business of this art not only to “teach”but also to “move, in order to convince”: and no eloquence can move unless the speaker himself has been moved. But whereas we make an aesthetic emotion the first and final end of art, Medieval man was moved far more by the meaning that illuminated the forms than by the forms themselves…For the Middle Ages, nothing could be understood that had not been experienced, or loved… .”Ibid., pp.173-74.

66 Ibid.,p.174.

67 A term used by Victor Bychkov to describe Fr. Pavel Florensky‘s understanding of symbol, which “has ‘two thresholds of receptivity,‘ an upper and lower, within which it still remains a symbol. The upper threshold preserves the symbol from ‘the exaggeration of the natural mysticism of matter,’ from ‘naturalism,’ in which the symbol is wholly identified with the archetype. This extremity was characteristic of ancient times. The Modern Age tends to go beyondthe lower limit, in which case the material connection between symbol and archetype is broken, their common matter is ignored, and energy and symbol perceived only as signs of the archetype, not as its energetico–material bearer.” V. Bychkov,“The Aesthetic Face of Being”,Art in the Theology of Pavel Florensky,SVS Press, Crestwood,NY, 1993, p.71.

68 “… We see in the realm of the senses, … a number of selfless feelings,which arise completely apart from the gratification or non–gratification of requirements; they are feelings from the delight in the beautiful … .Works of fine art are delightful not just for the beauty of outward form, but more particularly for the beauty of inward composition, the intellectual- contemplative beauty, ideal beauty. Where do such phenomena come from in the soul? These are visitors from another realm, from the realm of the spirit [intellect, nous].The spirit, which knows God, naturally comprehends Divine beauty and seeks to delight in it alone. The spirit cannot definitely prove what Divine beauty is, but, by carrying within itself the design of it, it definitively proves what it is not, expressing this evidence by the fact thatit is not satisfied by anything which is created. To contemplate Divine beauty, to partake of it and delight in it, is a requirement of the spirit and is its life– the Paradisal life. Having received information about Divine beauty through its binding with the spirit, the soul too follows in its steps, and, comprehending Divine beauty by means of its own mental image, it leaps with joy because within its realm it is presented with the reflection of that Divine beauty (delights), then itself devises and manufactures things in which it hopes to reflect it as it is presented to it … . That is where these guests come from- delightful, estranged from everything sensual, elevating the soul up to the spirit and spiritualizing it! I would note that, concerning artistic works, I am including in this class only those works in which the Divine beauty of invisible divine things serves as the content, and not those works which, although they are beautiful, all the same represent ordinary, mental-corporeal life or those very things which constitute everyday circumstances of that life. The soul seeks not only what is beautiful, being guided by the spirit, but also the expression of the beautiful in beautiful forms of the invisible world, to where the spirit by its action beckons.” St. Theophan the Recluse, The Spiritual Life and How to be Attuned to It, St. Paisius Serbian Orthodox Monastery, Safford, AZ,2003, pp.55–56.

Dear Father Silouan

Thank you for your well written and compelling article “Towards Fullness of Iconicity.” You have visited and addressed an important matter — a matter which, I believe, touches upon the foundation of iconography itself: Holy Scripture. Given your thesis, can we then say that the authenticity (“iconicity”) of Holy Scripture only resides in the original manuscripts? And, if so, how does this impact the LXX and (for that matter) any adequate translation of Sacred Writ? — Donald+

Dear Fr. Donald,

I do not believe that the “original manuscripts only” idea is (at all) what Fr. Silouan had in mind.

I think, rather, that he is asserting “how” we can be “faithful to” the originals. He is not asserting its impossibility, for in fact he argues for “how” we can be “faithful to” this lucidity.

All of Fr. Silouan’s words are designed to draw out the “best”, the “clearest”, the most “lucid” ways of achieving (not failing at arriving at) a concord with “the original”.

Any word that is true is true.

Any translation that speaks truth and no error is true.

Any icon that speaks truth and no error is true.

While each may never be identical one with the other (why should they be, for they are not), nevertheless all “material” may bear the truth to the degree of its ontological capacity to do so.

So, even if ALL Bibles and ALL icons were destroyed, and ALL Patristic and Conciliar Writings, the Church and her saints could simply “WRITE THE TRUTH YET AGAIN”, from her actual and true and live experience of Christ.

What matters is the “Eidos”, which is Christ the Logos Himself, not the “original” in a chronological and purely material sense.

In Christ,

Hierodeacon Parthenios

Dear Donald,

In fact, the foundation of iconography is the incarnate Word of God, the hypostatic Truth.

Likewise, the Word is the foundation of Holy Scripture. The letters are shining garments, from which emanate the Lord’s life giving glory. Holy Scripture has authority precisely because it embodies the Truth, it is an icon in words, in fullness of iconicity. Some translations have been acknowledged by the Church as the most lucid mirrors of the Truth; through the radiance and inspiration of the Spirit, they clearly reflect the Truth. Yet, the uncreated Truth is not limited by the symbols that manifest it. These mirrors (symbols) are not to be mistaken to be the Truth itself although they participate in the Truth in a sacred and mystical manner. If all of Holy Scripture and the best of its translations where to be burned, the Holy Spirit will once again inspire the pure in heart and guide them to the best written expression of the Truth. Also bear in mind that Holy Scripture arises from life in the Spirit within the Church. Holy Scripture being one of the expressions of Holy Tradition, but not its determinant. In short, we shouldn’t just see the matter of authenticity of Holy Scripture as an archaeological search for the most ancient or original manuscripts. We should be careful not to fall into the trap of historicism or literary criticism in these matters. Yes there are translations more reliable than others, but not one language can claim monopoly of fullness of iconicity when it comes to the written expression of the Truth. This would imply a limitation to the ineffable works of the Spirit.

Fr. Silouan