Similar Posts

(Editor’s note: this article was written by Martin Earle, Aidan Hart’s studio assistant who worked to create a commission they received for a statue of the Hodogetria. Martin can be contacted at mart_earle@yahoo.co.uk. )

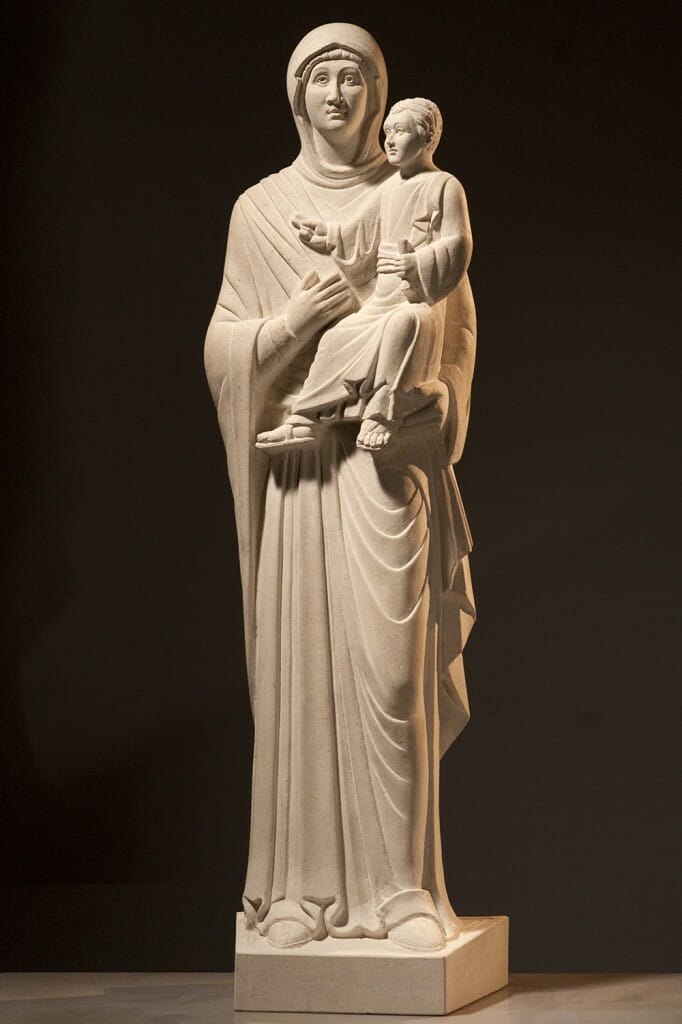

Theotokos Hodegetria, carved in limestone by the author, 2016, 37 x 8 x 7 inches (95 x 20 x 18 cm). Photography by Hugh Gordon.

I always brace myself for a bit of anti-Catholic sentiment when meeting an Orthodox Christian for the first time. A convert myself, I know that converts can be the worst. But this was something else.

I’d invited myself into the home of a celebrated iconographer only to find a very large and brilliantly rendered portrait of Henry VIII, legs astride, dominating the kitchen. Had Orthodox animosity towards Catholics hardened so much that they’d adopted Henry VIII as some kind of a hero, a saint even? Had they forgiven him his iconoclasm on account of his Catholic-bashing? Was I safe?

But the man sitting opposite me sipping tea from a large mug seemed utterly benign, a model of courteous welcome. He asked me about myself with a kind interest and didn’t even flinch when I came clean with my Catholicism. I told him about my studies at the Royal College of Art and my love of the Romanesque, which he shared. He noticed me looking nervously at the portrait looming over us.

‘It’s my son’s’, he said. ‘He’s studying the Tudors at school. Not bad for a nine-year-old, don’t you think?’

It happened that I had walked into Aidan Hart’s kitchen, three and a half years ago, at the perfect moment. He was snowed under with work and looking for help. I have been privileged to call myself his apprentice and assistant ever since.

A frequent theme of our conversations in the studio—in the midst of carving, painting, and making mosaics—is the need for Christians in the West to digest and interpret Byzantine art rather than merely copy it. Our worship is not the meeting of a historical recreation society. It is the here-and-now source of our life. Despite my passion for the icon, I’m sometimes put off by the obsequious way that some British Catholics treat Orthodox iconography, especially icon painting. There are examples of peerless liturgical beauty from our own Western culture that were created during the very same period that today’s icon revival often draws on for its models. But they are mostly overlooked.

One of the most exciting things about the Romanesque is its habit of drawing on and reinterpreting Byzantium. The Romanesque was not very Roman; the art of the High Middle Ages was an energetic collision between the Northern European and Byzantine styles. What is left of it in Britain alone shows that it could produce works that are as full of meaning and power as the Byzantine models it drew on, but suffused with their own unique spirit. Take, for example, the remains of a carved wooden crucifix discovered a century ago in the wall of a small church in Gloucestershire. These two little fragments, Christ’s head and foot, are the sole survivors from all the pre-Reformation rood crosses in Britain. Yet despite their size and incompleteness they beautifully express the mystery of Christ’s death: the face full of an inexpressible peace, the toes bent in anguish.

South Cerney Crucifix, polychromed gessoed wood,1130 (circa), 6 x 2.5 x 3 inches (15.5 x 7 x 8cm), British Museum, London.

As well as providing a link between Byzantium and Western Christendom, such iconographic works demonstrate that carvings—even carvings in the round—can be just as theologically expressive as painted icon panels. They need not be naturalistic. They can express the paradoxical form of Christianity, its simultaneous humanity and divinity, just as effectively as a painted icon. It is true that the panel icon allows for greater freedom in the rendering of space and use of multiple perspectives and that, in a certain sense, a carving in the round can seem flatter than a well-executed painted icon. The genius of the festal icon is that rather than placing a feast within a space it places space itself within the feast. It is also true that statues tend to have the problematic feature of a back as well as a front. They can be seen from behind and possibly treated as objects, rather than being encountered in face-to-face contemplation. Yet the more dogmatic Orthodox objections to three-dimensional carving seem unreasonable to me. If God chose to manifest Himself in three dimensions, how could it be wrong to depict Him in three dimensions? If God chose to be circumscribed by a human form, how could it be wrong to depict that form as a form? Could it be that statuary has something unique to offer, its own particular emphasis?

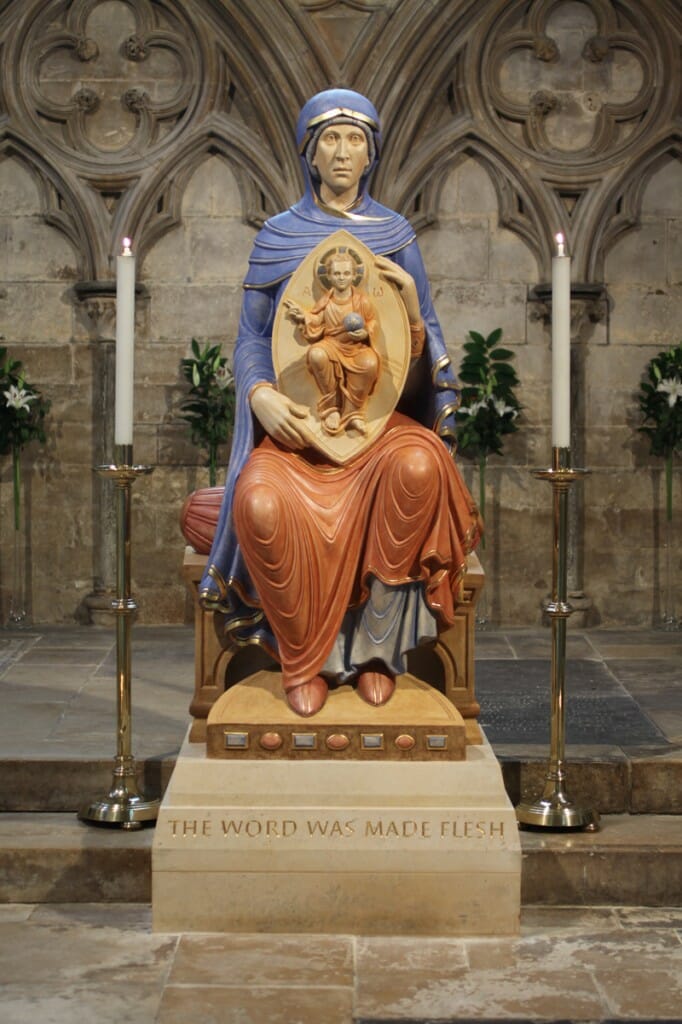

Our Lady of Lincoln, Aidan Hart, polychromed and gilded limestone, 2014, height 7′ x 6″ (2.3 metres), Lincoln Cathedral, Lincoln.

Because of all this I was overjoyed to be given the opportunity to help Aidan carve a statue of The Mother of God for Lincoln Cathedral. For three happy months we carved outdoors, gradually revealing and refining the form as winter turned into spring. I learnt a tremendous amount. Our conversations, interspersed with periods of concentrated silence and occasional blasts of John Coltrane, often turned back to Henry VIII. Lincoln Cathedral, for a time the tallest building in the world, had been without a statue of the Virgin Mary since the English Reformation. Aidan’s statue now sits at the cathedral’s eastern end. In a language entirely iconographic, it speaks to the space—its architecture, its history, and its present—as no painted icon could.

I was able to apply much of what I had learned from the Lincoln commission to another carving I recently completed. Soon after Our Lady was installed and painted, Aidan asked if I would make a statue based on the famous Theotokos Hodegetria ivory for Joseph Gleason, an Orthodox priest at Christ the King Parish in Omaha, Illinois. I was to carve most of the piece, but Aidan was to help with the fine-tuning, especially of the faces.

The original Theotokos Hodegetria, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, is something of an anomaly. Although there are a handful of other historic liturgical statues carved in the round in the Orthodox world, this is the only extant example from Byzantium itself. It is small—just over a foot high—but the carving is exquisite and intricate. Ironically, the rarity of three-dimensional carving in Byzantium is underlined by the fact that the Theotokos Hodegetria ivory is perhaps no such thing. From the front or back, it resembles ivory reliefs from about the same period, but when viewed from the side it seems thin and insubstantial, almost as if two relief carvings have been metaphorically stuck together.

Theotokos Hodegetria, ivory, late 10th century to early 11th century, 12.5 x 3.5 x 2 inches (32.7 x 9.2 x 5.2 cm)

Father Joseph asked that we be as faithful as possible to the original when carving the work. I sometimes wonder whether the carvers of the Romanesque cathedrals were given a similar brief. Whether, in an age when mechanized replication was unheard of, they really were trying to copy as closely as possible some model they had received or caught a glimpse of, perhaps a relief icon on a Byzantine ampulla carried back from Holy Land. Yet the iconography that emerged, full of reverence and humour, is unique. Inevitably, even copies reveal something of their makers.

Last week, I watched as my completed carving of the Hodegetria was bundled unceremoniously into a delivery van. Working in Aidan’s studio has made such slightly surreal scenes familiar to me: The Virgin in the back of the van, the broom handle resting on a mosaic of Christ crucified, the bulging folders labeled ‘Angels’ and ‘Archangels’. These sights are a reminder that the work of the icon is the work of incarnation: the mingling of heaven into our daily life. Despite having worked on the statue on and off for a year, it was not difficult to part with it. It was never mine to start with. It was a copy in more senses than one: not only of one particular Byzantine ivory, but of God’s own work in the world.

Congratulations on your completed statue. I had the privilege of visiting the atelier in Nov 2013 with Dick Temple, when you two were making all that marble dust, and I was very impressed by the final result in Lincoln Cathedral.

It’s nice to hear the background on your coming to your current position. May you have many years in this artistic endeavor.

Michael

I remember your visit to the dusty studio well. I trust that you are well, and that the icon hunting is continuing successfully! Martin

I am Orthodox ( a convert as well) and I have admired that Byzantine statue from the first time I saw it on line. When I saw the statue in Lincoln I was hoping to purchase a small home version of that statue but have not seen this available from the church store. The new statue that you have carved is even more beautifull. How can these be purchased for my home or icon corner?

I’m really glad you enjoy the statue, though I can’t say it competes with Our Lady of Lincoln! I have made a silicon rubber mould, so it is possible to make casts of the Hodegetria – although, at 3ft (92cm) high, it may be a little large for most home icon corners? Just get in touch if you are interested.

Thank you for your beautifully written article and for its insightfulness. Your statue is very beautiful. I am a newly received Orthodox and have been journeying towards it for 40 years as long as I have been a painter. I am so enjoying the contributions to this Orthodox Arts Journal. Thank you very much

Btw, Fr. Gleason, ordained as a Western Orthodox Priest, serves in Omaha, Illinois, not Nebraska.