Similar Posts

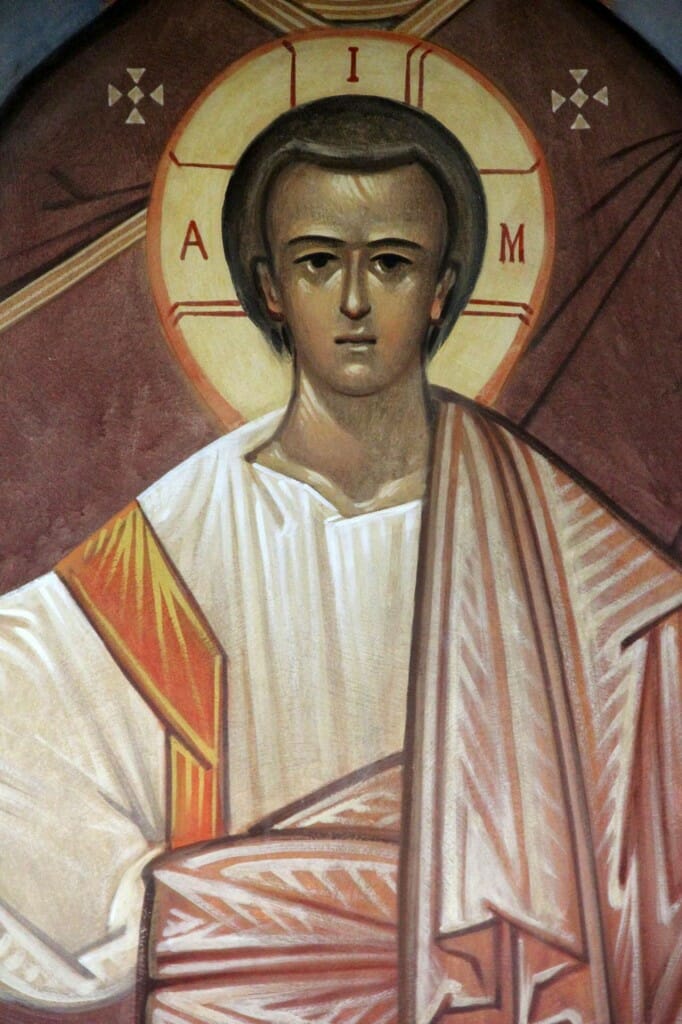

Editor’s Note: Seraphim O’Keefe is a promising young iconographer who has already done some remarkable work. We are pleased to feature his very interesting life story here, as well as images of his most recent major project – wall paintings at St. Cyprian Orthodox Church in Midlothian, Virginia. It is clear from the quality of this painting that Seraphim is one of the most talented up-and-coming iconographers in the USA.

A. Gould: Seraphim, tell us about your background as an artist. You studied painting in the Republic of Georgia. How did you wind up so far from home, and what was that experience like?

O’Keefe: My desire to be an artist was inspired first of all by my dad. From his childhood, my father had a talent and zeal for drawing, which he followed through study at Parsons School of Design, at Cooper Union in New York City, and into his career in marketing. Growing up, my three brothers and I were all inspired to identify with visual art, and we are all still pursuing it in various ways. In my teenage years, art became the central way I related to life and explored who I was. My work at that time was experimental, postmodern, and often quite dark.

In my eleventh grade year, I met a man named John Wurdeman, from my hometown of Richmond Virginia, who lived as an artist in the Republic of Georgia. He had gone from MICA in Baltimore to the Surikov Institute in Moscow seeking the most intensive classical art education he could find. He studied in the studio of the master Vyacheslav Nikolaievich Zabelin, becoming the first American to complete the institute, and then moved to the village of Sighnaghi in Georgia where he married Ketevan Mindorashvili, the leader of a Georgian sacred/folk ensemble. He invited me to join a group of five painters from America for a summer painting practicum in Georgia led by him and his classmate, Ilya Yatsenko. I was the youngest in the group; the other four were professional artists.

None of us anticipated the wondrous land that awaited us in Georgia. Sighnaghi is a mountaintop village overlooking the fertile Alazani valley where wine has been made for thousands of years, which stretches out towards the snow-capped Caucus Mountains. We put in long hours painting and drawing from life, but the summer was also saturated with amazing characters, Georgian song, dance, feasting, and spiritual activity. I had never seen such a rich and adventurous culture. My teachers saw that I was eager to learn, and they invited me to return as their apprentice after high school. I chose this apprenticeship over college because it promised a more intensive classical education, but also because I had come to love and admire my teachers and their families, and I was enchanted by their way of life.

As an apprentice, I lived at my teachers’ side, usually in Sighnaghi with John, but sometimes for a season with Ilya in a log cabin in a remote Russian village. We worked long hours painting and drawing portraits, still lifes, and landscapes, and I had various drawing exercises to do on my own. Throughout every task I was in dialogue with my teachers; they corrected and guided me, and I watched their ways of approaching our subjects. We spent time looking at the works of masters and discussing our work in this context. The aim was always to train my eye to see things in relationship, and to express them as proportions. For the final year of my studies, I went to Moscow where I rented a studio and studied under Ilya’s teacher, Nikolai Ilarionevich Kozlov, who gave me a very rigorous schedule of academic drawing work.

For me, the advantage of apprenticeship was the opportunity to develop such a bond with my teachers. I became like a member of their families, ate with them, travelled with them, exhibited art, danced, sang, celebrated, and went through many adventures with them. They helped me through many of my most difficult times, and to this day I still feel I am proceeding under their guidance, though I rarely get to see them in person.

A. Gould: And did you discover the Orthodox faith in Georgia as well?

O’Keefe: Indeed. I was an atheist growing up, but by the time I went to Georgia, I was very hungry spiritually. Both John and Ilya, along with their families, are serious seekers, so I joined their search, soon joining them in the Orthodox Church. This led to many adventures and trials.

A. Gould: Tell us how you decided to pursue iconography as a serious vocation.

O’Keefe: After my conversion to Orthodoxy, I began to intersperse my studies with monastery visits. Eventually, I wanted to try monasticism, and I went to a monastery in Georgia, where I lived for about fourteen months as a novice. Since I was trained as a painter, the abbot brought in teachers so that I could learn iconography. When I left the monastery, I returned to my teachers and to painting from life, but gradually my interest in icon painting grew. After my studies in Moscow, I returned to America, and vacillated between painting and exhibiting fine art, graphic novel type work, and iconography. I was discouraged with the current culture of selling fine art, which usually involves presenting oneself as a sort of exotic breed of person, the “artist”, and convincing wealthy people to want your work.

The summer before we were married, my wife Ilaria and I spent two months in Alaska, in a community where Ilaria’s talent for singing and teaching music, and my talent for iconography, were called upon. The experience of working on songs and images in a community whose dynamic life called out for expression through each member’s talents, inspired us both. As we left at the end of the summer, the priest said to me with inspired joy; “You HAVE to learn iconography!” His words resonated. I went to spend two months at Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, where they generously instructed me in egg tempera technique. Thereafter I consulted Fr. Andrew Tregubov whose guidance has been important to me, as well as other iconographers. After our wedding in 2010, Ilaria and I went back to Georgia, where our expenses were very low, and I was able to begin painting icons full-time.

A. Gould: Which historical icons and iconographers do you feel drawn to emulate?

O’Keefe: I eagerly study everything that I can get hands on. Recently, the masters who have inspired my wall paintings the most are probably Theophanes the Greek and the Master of Volotovo Polye, both of whom worked in thirteenth century Russia, and are closely connected. Most of their work is lost now, but their frescoes from Novgorod have been well photographed. I suspect they are the same person, but I think most art historians say otherwise. In any case, these frescoes are painted with stunning spontaneity, and depicted people full of expressive immediacy. Their compositions are simplified to the essence of the subject, emphasizing the personal character of the encounter of man and God. Their freedom and playfulness somehow strengthen the subject’s solemnity. Their lines sing. I think these qualities are particularly appealing to the modern eye.

I also lean on the work of Father Gregory Krug and Leonid Ouspensky. Here too, simplicity, spontaneity, and human expression are emphasized. The creativity with which they express the tradition reminds us that the faith is not to be preserved as in a museum, but incarnated. These two have been a bridge for me to the old masters. My teacher John, and his teacher, V.N. Zabelin, are both especially masters of color, and Fr. Gregory’s work has helped me to see how their sense of intuitive, living color can be brought into iconography.

Most recently, living near the Cloisters museum in New York, I have been interested in studying Romanesque iconography. I find the bold colors and the rhythmic patterns of drapery exciting.

A. Gould: Was Holy Cross Church in Linthicum, Maryland your first major commission? How did you end up with such a substantial first project?

O’Keefe: By the prayers of St. Boniface. Holy Cross was indeed my first wall painting commission. I had been friends with the parish community for seven or eight years prior to the commission. About a year after our wedding, my wife and I visited Holy Cross on a road trip. They had recently been given a relic of St. Boniface, and the priest there, Fr. Gregory Mathewes-Green asked me to paint an icon for it. I was eager for commissions. The next day, we visited St. Vladimir’s seminary, and in an unrelated incident, someone there commissioned me to paint another icon of St. Boniface. Getting two commissions in two days was enough of a special coincidence at that time – and for both to be for St. Boniface meant for me that the Saint was at work in my life. I read his biography and painted the icons.

When I brought the finished icon to Holy Cross, they were well pleased, and Fr. Gregory asked right then about my availability to do the wall paintings they were planning for the twentieth anniversary of the parish. I was willing, but I think Fr. Gregory took a big risk in hiring me, so inexperienced. The parish supported me through their prayers and enthusiasm, and good came of it. You can certainly see me learning as I go in those wall paintings, but you can also see the holy adventure it was. Most importantly, the parish community’s walk with God comes through in the images.

St. Boniface was included in the final image of the two-year project, in a group of missionary saints, and his image came forth especially strikingly, again signaling his role in the whole thing. The risk the parish took on me, and the help of the saints allowed me to take the unlikely step into painting churches professionally.

A. Gould: Seraphim, you’ve recently completed your second major work – painting the chancel of St. Cyprian Orthodox Church in Midlothian, Virginia, and it is photos of that project that we are featuring in this article. Tell us how you came to work at this church, and what challenges and opportunities it presented.

O’Keefe: Midlothian is a suburb of Richmond Virginia, my hometown, and I had known this parish for about twelve years leading up to this commission. I had often discussed the possibilities for wall paintings at St. Cyprian’s with their priest, Fr. David Arnold, in the years before they were ready to begin this work. A group from the parish came up to see the wall paintings at Holy Cross as I was finishing them, and they decided to commission me for their chancel imagery. The change of dynamic between the two parishes taught my wife and I a lot about the nature of our vocation. More and more I see this work as a ministry of listening for and giving voice to the particular conversation that exists between God and the community.

The first challenge here was our desire to make the wall paintings as permanent as possible. With your advice, Andrew, we decided to essentially build a wall, overtop the existing latex-painted drywall, consisting of fiber cement board onto which plaster was applied. This entailed a considerable expense for the parish, but we all felt it was worth it – the plaster itself interacts pleasingly with light and sound, and it makes a permanent surface for the images. This part of the project also bought me extra time to develop my preliminary drawings before starting work on the walls. To work from these drawings on that beautiful plaster wall was a great pleasure.

The unusual shape of the chancel wall at St. Cyprian’s was another challenge. It is much wider than it is tall, and it has a flat rather than a half-dome ceiling. The top of the iconostasis is a straight line across at about half the floor-to-ceiling height. All of these factors made zones with horizontal dividing lines seem especially undesirable. This made the question of how to compose the Theotokos – the central image of the apse, which embodies its incarnational purpose – especially challenging. The solution of depicting her in a mandorla allowed the other elements to come together in an arrangement that draws all of the imagery, and thereby the whole dynamic of the liturgical services, in towards the moment of communion, the union of God and man.

I strongly prefer to execute wall paintings on-site, because it is so important for me that every shape and color interact with the different lighting conditions throughout the day, and I pay attention to the dynamics of the community during worship, so that in every way the images can grow out of the particular relationship of God with the people. Little is so inspiring for a community as seeing its own life and vision expressed.

The founding priest of St. Cyprian’s, Fr. George Detrana, invested in a wonderful series of icons by the hand of Mme. Maria Struve, a student of Leonid Ouspensky. The parish identifies strongly with these icons; they have interesting stories about how they were chosen and how parishioners would travel to France to pick them up to bring home to the house-church in which the parish was originally located. This series includes the four large icons on their iconostasis. Fr. George was a devoted student of Fr. Alexander Schmemann, who was a friend of Mme. Struve; the current priest, Fr. David Arnold, also identifies with this lineage through his education at St. Vladimir’s seminary, and he had this in mind when he chose the architect, Fr. Alexis Vinogradov, who is closely tied to that community as well. All of this set a precedent for me to pay close attention to the Paris school of iconography primarily defined by the work of Leonid Ouspensky and Fr. Gregory Krug; the very thing which I myself was eager to do.

A. Gould: There are several features of the chancel painting that are somewhat unusual – especially the white background and the borderless compositions. The figures float together in this light-saturated space. It is so different from the dark blue with rigid red borders that we typically see. Why did you choose to paint with this delicate use of light and compositional space? Do you suppose there is something particularly modern or American about this bright simplicity?

O’Keefe: Bright backgrounds and simplicity of composition are very characteristic of the Paris school of iconography, and I notice these tendencies appearing in the works of contemporary iconographers around the world. I think that bright and open spaces, and bold, simple compositions are especially welcoming to the modern eye, including my own. In my experience, people more readily respond with openness to the other than they do when entering a dark or densely adorned space. But each place calls for its own aesthetic.

A. Gould: Can you explain the rationale behind the compositions you chose, and where you placed them?

O’Keefe: The overall theme could be expressed in the famous phrase, “God became man so that man might become God”, from St. Athanasius’s “On the Incarnation.” The program of icons is designed to interact with and interpret the church’s liturgical services, reminding the gathered faithful that this theme directly involves us.

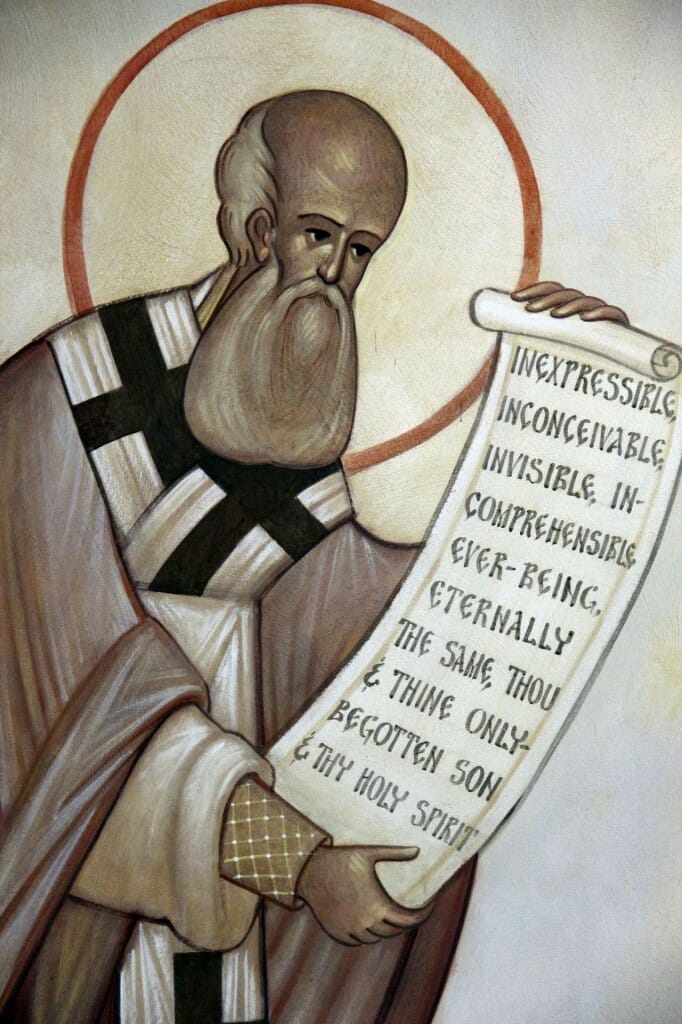

The ceiling features the etimasia, the prepared throne of God. This is not easily visible from the nave, and to see it from within the sanctuary requires looking directly up, so that in usual practice, this image plays the role of “something happening above”, which is appropriate to its meaning. The etimasia represents the place of the transcendent God, “inconceivable, ineffable, invisible, incomprehensible…” to Whom we have access through the cross of Christ. This is the God Who became incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and these two images are related here by the similarity of their presentation in mandorlas. The etimasia here is directly above the physical altar table, and interprets its meaning. The dove perched on the throne represents the Holy Spirit, Who we call down upon the gifts during liturgy.

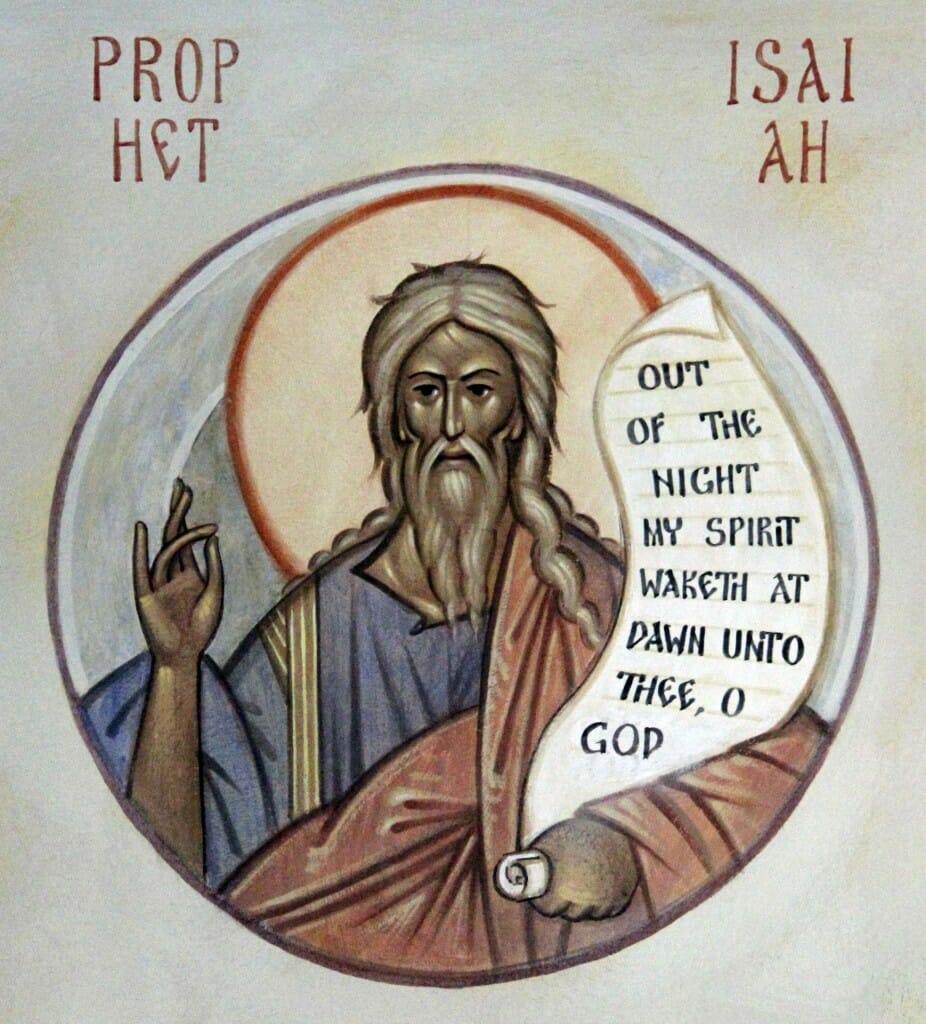

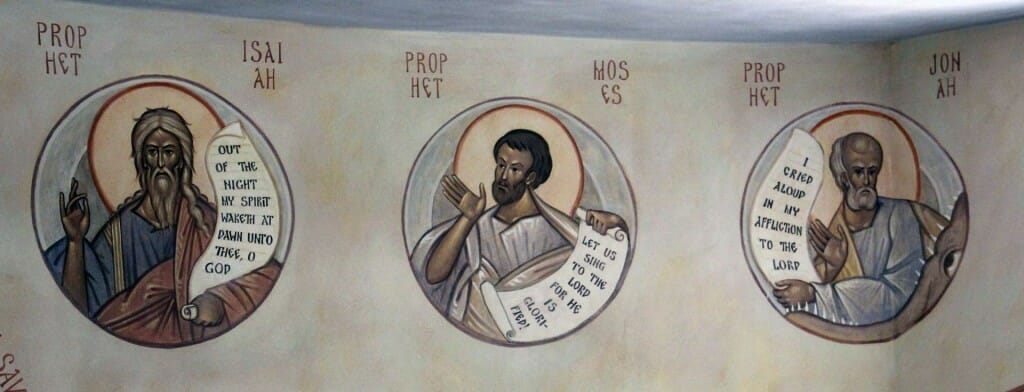

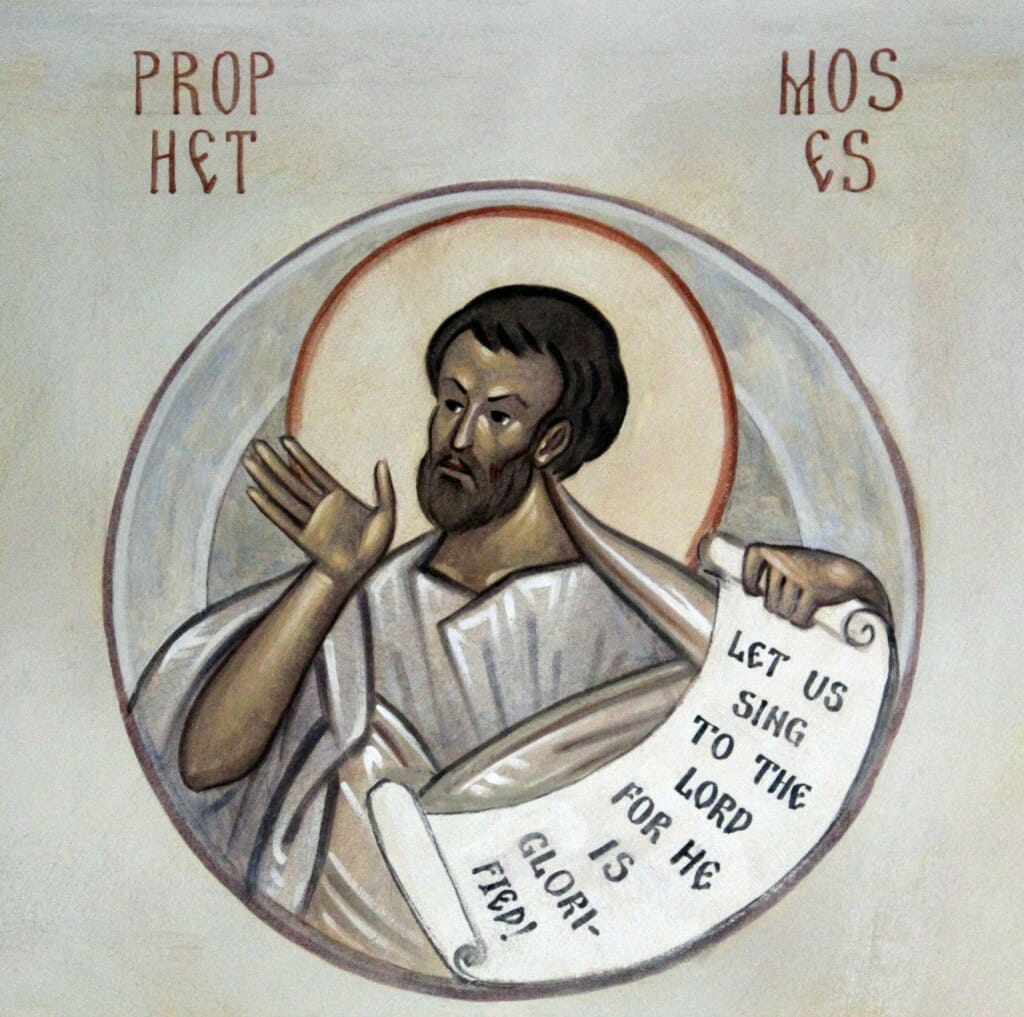

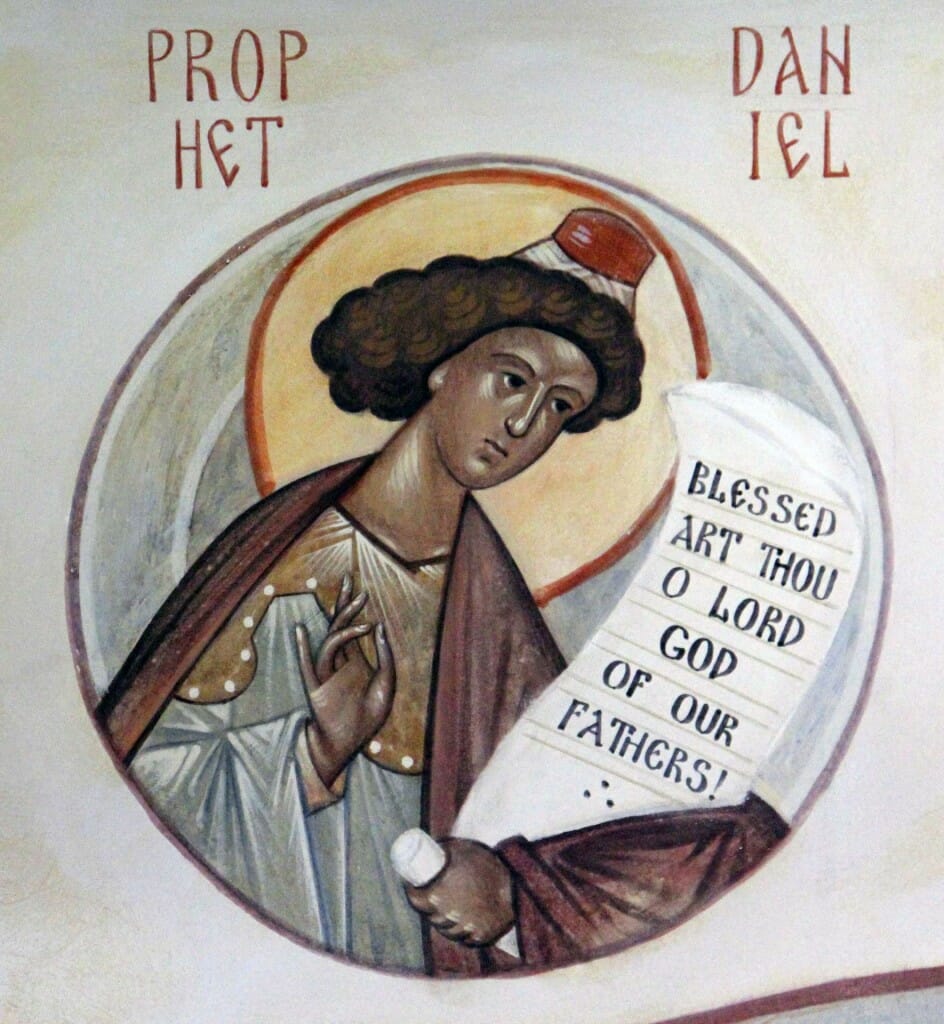

The eight smaller mandorlas around the top of the apse wall, close to the ceiling, depict prophets, four on either side of the Theotokos. Together, these nine mandorlas present the nine odes of the canon hymns which make up a prevalent part of Matins and other daily services. The prophets here are the authors of the nine canticles on which these odes are based, and they hold scrolls bearing the first lines of their canticles, each suggesting a certain attitude towards the Lord. The transcendent God suggested by the etimasia above is the One the prophets longed to see. As with the hymnographic order of the nine odes, the prophets’ gestures anticipate the time when this longing would be answered – in the ninth ode – whose author is the Virgin herself. The first words of her canticle, “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior,” proclaims the attitude of mankind’s acceptance of God’s coming in the flesh.

The Mother of God is the central image, which interprets the sanctuary as the womb-like space wherein God comes to be incarnate through the Eucharist, uniting the faithful as the body of Christ. Jesus’ presence is emphasized as the center of the circle, and the outward movement of His blessing, as well as His mother’s upward supplicatory gesture, carries into the surrounding shapes and lines. Archangels Michael and Gabriel flank her on either side with fans that might also call to mind the coal bearing tongs From Isaiah 6. All this forms a cross-shaped movement, which is brought out by the diamond-shaped element of the mandorla. Horizontally, it caries Christ’s blessing gesture outwards. Vertically, it relates to the etimasia above and to the chalice on the altar table depicted below.

The Mother of God is the central image, which interprets the sanctuary as the womb-like space wherein God comes to be incarnate through the Eucharist, uniting the faithful as the body of Christ. Jesus’ presence is emphasized as the center of the circle, and the outward movement of His blessing, as well as His mother’s upward supplicatory gesture, carries into the surrounding shapes and lines. Archangels Michael and Gabriel flank her on either side with fans that might also call to mind the coal bearing tongs From Isaiah 6. All this forms a cross-shaped movement, which is brought out by the diamond-shaped element of the mandorla. Horizontally, it caries Christ’s blessing gesture outwards. Vertically, it relates to the etimasia above and to the chalice on the altar table depicted below.

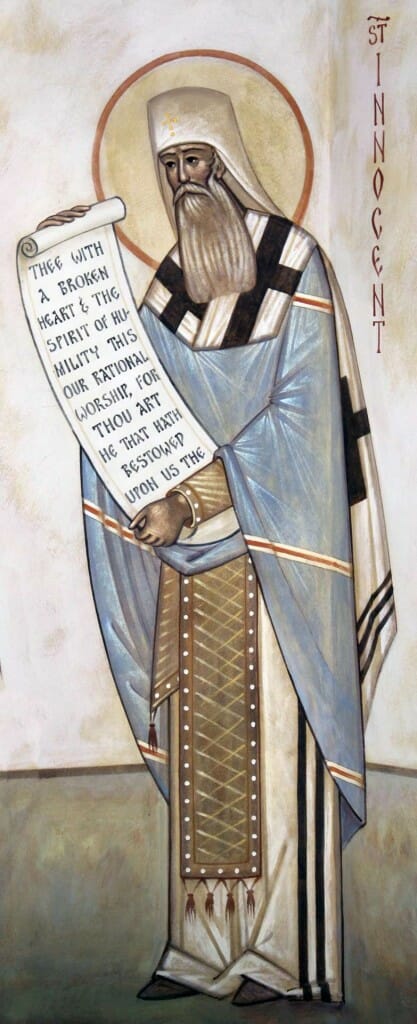

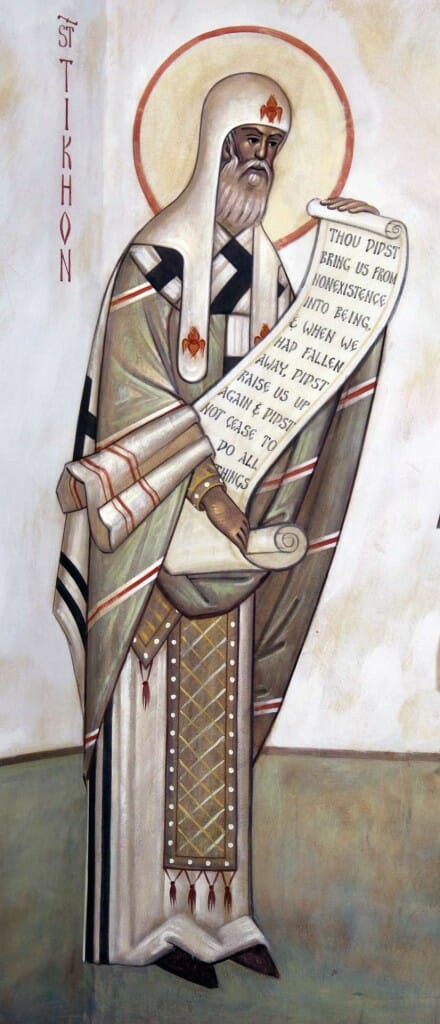

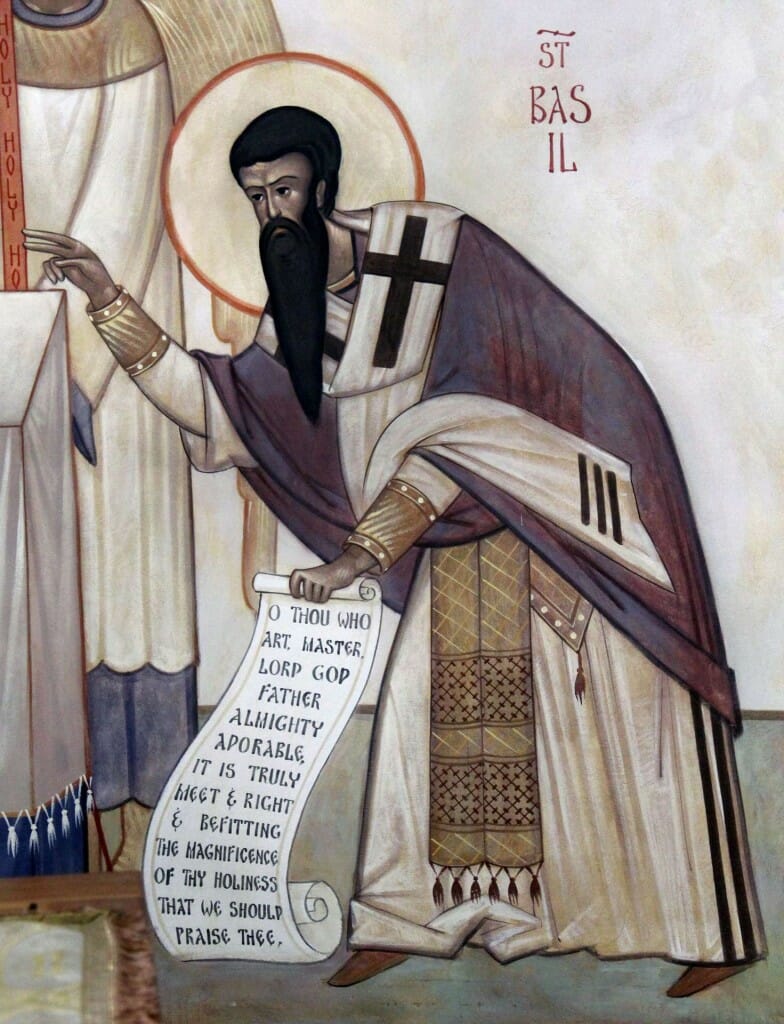

If the movement from the throne of the transcendent God to the incarnation represents “God became man”, the movement towards the chalice on the altar table in the lower zone of iconography represents “so that man might become God.” Here, St. John Chrysostom and St. Basil the Great, to whom are attributed the two most commonly used arrangements of the Divine Liturgy texts, are serving at an altar also attended by angels. They hold scrolls bearing the epiclesis found in each of their liturgies, and this text continues into the scrolls of the bishops standing behind them, emphasizing the continuity of worship across time and geographical distance. Behind them stand St. Gregory the Theologian of 4th century Cappadocia, St. Cyprian of Carthage from 3rd century Africa, and following them, Saints Tikhon and Innocent, who both served in America in the 20th century. This image continues into our own liturgy, when the faithful hear the same words read during the epiclesis, reminding us that as we worship, we join with the whole Body of Christ from all times and places, and with the angelic hosts. That is why these figures are shown life-size and standing on ground level amongst the faithful – their movement reflects the stance of the people gathered in worship.

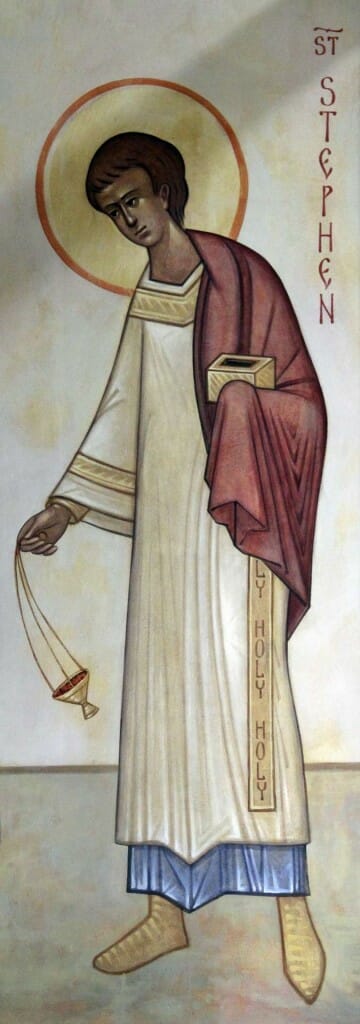

Following the American bishops, from the north and south walls, are a priest and then a deacon on either side, which is an unusual addition to this subject. The priests, St. John of Chicago and St. Jacob of Alaska are both martyrs who served in America; St. Jacob is the first American-born Orthodox priest, and St. John is the first martyr of the Bolshevik revolution. The deacons are just inside the “deacon doors” of the iconostasis; St. Stephen, the deacon whose martyrdom is told in the book of Acts, and St. Olympia, a fourth century monastic and friend of St. John Chrysostom.

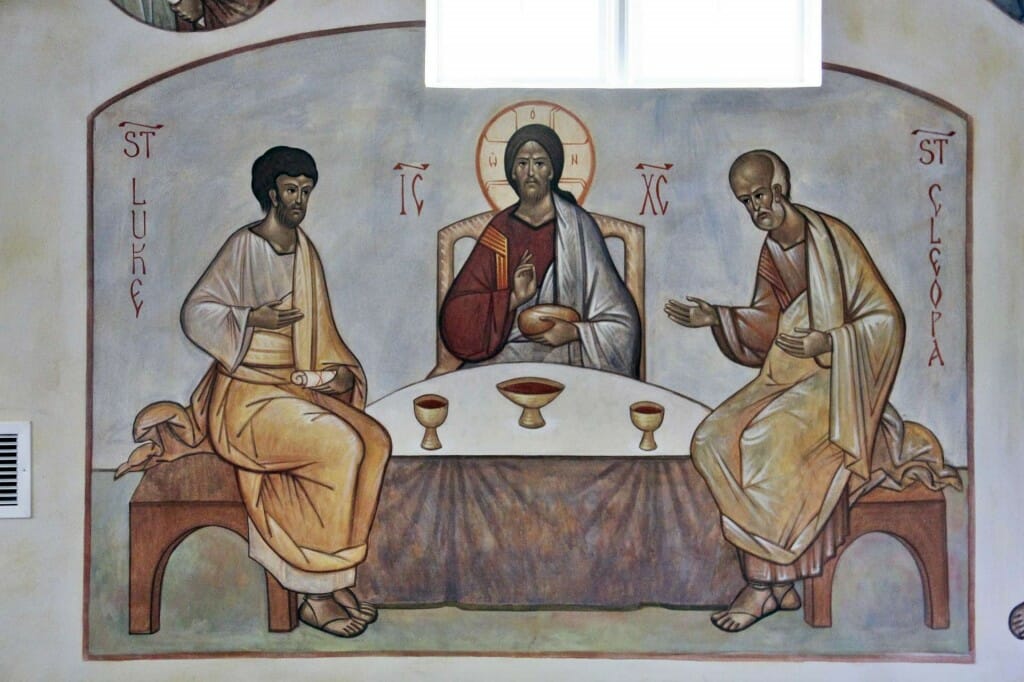

Above these figures on the north and south walls are two resurrectional scenes. The appearance of the risen Christ to Luke and Cleopas at Emmaus interprets our Eucharist by the disciples’ recognition of Christ in the moment that he breaks the bread. Jesus’ appearance to the disciples at the sea of Tiberias reminds us of reconciliation as preparation for communion, as Peter dives into the water to swim to Jesus Whom he had denied three times, to be reconciled through his response to Jesus’ thrice-asked question: “Do you love Me?”

Above these figures on the north and south walls are two resurrectional scenes. The appearance of the risen Christ to Luke and Cleopas at Emmaus interprets our Eucharist by the disciples’ recognition of Christ in the moment that he breaks the bread. Jesus’ appearance to the disciples at the sea of Tiberias reminds us of reconciliation as preparation for communion, as Peter dives into the water to swim to Jesus Whom he had denied three times, to be reconciled through his response to Jesus’ thrice-asked question: “Do you love Me?”

A. Gould: There is one icon I don’t remember ever seeing before: Saint Olympia the Deaconess. She is portrayed like a deacon in the modern sense, holding a censer. Is there precedent for this image?

O’Keefe: I think so. We do not know just what a female deacon would have worn in the fourth century, but I saw these vestments as a simple way to indicate her diaconal service, as well as to relate the service of the deacons to the service of the angels standing at the altar, who here wear identical vestments. As I understand it, women deacons in the early Church primarily assisted with women’s baptisms, a role which eventually became unnecessary. However, it is not uncommon for nuns to have duties in the altar, and in the monasteries where I have seen this, the nuns routinely cense during services. I went about designing this image with advice from my mentors.

A. Gould: You paint your murals, and even some panel icons, using silicate paint on lime plaster. I use this same plaster and paint in the churches that I design, and I was asked to write the construction specifications for the application of the plaster in St. Cyprian church. So I have a special interest in this medium.

I am especially pleased to see how fluently you work in silicate paint. Some iconographers, accustomed to acrylic, find it frustrating to use and fight against its characteristics. But your work has amazing economy of brushstrokes. It is clear that you use silicate paint to great advantage and efficiency. Your technique is completely exposed – no moves appear concealed by later brushstrokes. You must have great confidence in your command of the medium. Can you tell us, as an artist, how it handles, and what advantages it gives you?

O’Keefe: I am so glad that you promote the use of silicate paint for church wall paintings – I think it is the best option in most cases. It is designed to be more permanent even than fresco, and it has the same visual qualities that make fresco ideal for church wall paintings: brightness, transparency, and a mineral matte finish. Unlike acrylic paint, it allows the plaster substrate to retain its luminosity and warm, solid appearance. But unlike fresco, silicate paint is applied to dry plaster, so it does not require the painter to apply plaster section by section, completing the painting of each section before the plaster dries. The church can complete the plaster work all at once, as far in advance of the iconography project as desired, and all that remains to do is paint. For me, this meant that I could build up the entire program of chancel imagery simultaneously.

I use the “Design Lasur” system of silicate paint from the Keim company, which was recommended to me by Vladimir Grigorenko for its transparency and relative ease of use. The paint comes ready to use, the colors are made of mineral pigments and can be mixed freely. I keep the colors in squeeze bottles, and I put them out on ceramic palettes to mix as I paint. There is a special dilution liquid for thinning the paint. As with any medium, the color range and paint behavior take some getting used to. Having worked in watercolor, egg tempera, oil, and various other media over the years, I found silicate paint relatively simple to learn. I think of acrylic as the least instructive medium, because it is inert and opaque, and it requires little visualization before action. Silicate paint requires this visualization because, as wet plaster looks darker than dry, this paint lightens as it dries. It dries and becomes permanent very quickly.

The color range also requires some practice initially; it can feel limited at first, but over time I have learned how to obtain a wide range of colors from it. After four years of using this paint, I am still often surprised at new effects I can produce. Only very rarely do I use the colors at their full brightness potential.

A. Gould: How do you find people react to your style of painting? Does anyone object that it is too austere? Or do people find they can connect with the icons better due to their straightforward simplicity?

O’Keefe: I do find that simplicity and readability help people connect with the image. In the churches I have painted thus far, I have had the blessing to be part of the community, along with my family, throughout the project. This has allowed me to learn about giving voice to the life of the community through the iconography. To me, this does not entail working out what image will go where with the parish council; primarily, I work closely with the priest to make decisions. Rather, it entails a certain kind of watching and listening, and dependence on the prayers and energy of the community. There is no formula to make this work, but when it happens, the community recognizes the images as their own. Sometimes people tell me that they feel as though the images were always on the wall, but hidden, and that as they progress it is like a fog is clearing, or something to that effect. It often feels that way for me, too.

A. Gould: Last year you enrolled at Saint Vladimir’s Seminary. What are you studying there, and what do you envision as your future career path?

O’Keefe: I am doing the three-year Masters of Divinity degree. This is the same course of study one takes to prepare for ordination to priesthood, but I am not seeking ordination, or any particular career change. The opportunity for study arose, and my family decided to go for it. Of course, the theological education will inform my work as an iconographer. But also, as we have progressed, my family has found that our work brings many opportunities for ministry. My wife has been able to minister through her musical skills, and in other ways as well. We seek ways of building and strengthening community in the Church, especially through the arts. If this eventually involves teaching or taking on apprentices, I want to be able to responsibly present the art within the context of the life and theology of the Orthodox Christian Church.

A. Gould: Do you have any thoughts on the state of iconography in America in general? What are your hopes for the future?

O’Keefe: I think iconography has a special role amongst the visual arts in our times. It is art made for a community, to express its life, values, and aspirations. And it is art that a community lives with and interacts with, day after day and year after year. It is part of a whole symphony; it organically interacts with the architecture, the liturgical objects and actions, the poetry and music of the services, all the sounds, scents, and motions. But even more, it interacts with the deep parts of people’s lives; on a daily basis, they are trying to live the life that icons express. People come to the church during their hard, dark times, in their times of joy and celebration, and through times of transition and growth. As they encounter the images during these times they will see them in new ways, and the meaning of images will develop for them. Not many artists have this kind of opportunity. For this reason I think we should try to make iconography that expresses the great dignity and worth of human life, and our high calling. I see you striving for this in the churches you design, Andrew. We should walk in to the space and sense our high calling. The vast majority of images that we see around us in our culture are calling us anywhere but higher and deeper.

On a practical level, for iconographers, I think that this means that we need to learn how to draw. This is a matter of respect. I am preaching this to myself, first of all. We need a full set of tools in our toolbox. It takes courage to learn how to love spending time with a pencil, but it is very much worthwhile.

A. Gould: Thank you, Seraphim, for this most interesting interview.

Seraphim O’keefe’s website can be viewed here.

I wish every blessing on this work and the thought behind it, and the man behind the thought, and the wife and family behind the man, and the parish communities who have and will collaborate with them; and bless God for these precious vessels.

Thank you to Seraphim for speaking so eloquently about the participatory role of the commissioners of the icon in the icon’s creation and the interconnectedness of the church artist in the church community.

The topic of what is needed pastorally by the American viewers of iconography is an immensely fascinating and important topic, and I thank Seraphim for bringing up this pastoral dimension in which the particularities of the viewing audience is of consequence. I feel that the pastoral ministry of iconography not to the worldwide Orthodox audience but rather to a particular family or parish often is painfully absent in discussions of church art.

Andrew, to your question of the depiction of a deaconess – I have always assumed that the famous mosaic of St. Empress Theodora with Attendants in the San Vitale Basilica in Ravenna depicted her with a deaconess at her left hand followed by the empress’ own sister, and then by other lower attendants. Does anybody know if this is a plausible interpretation of that composition?

with your prayers,

baker