Similar Posts

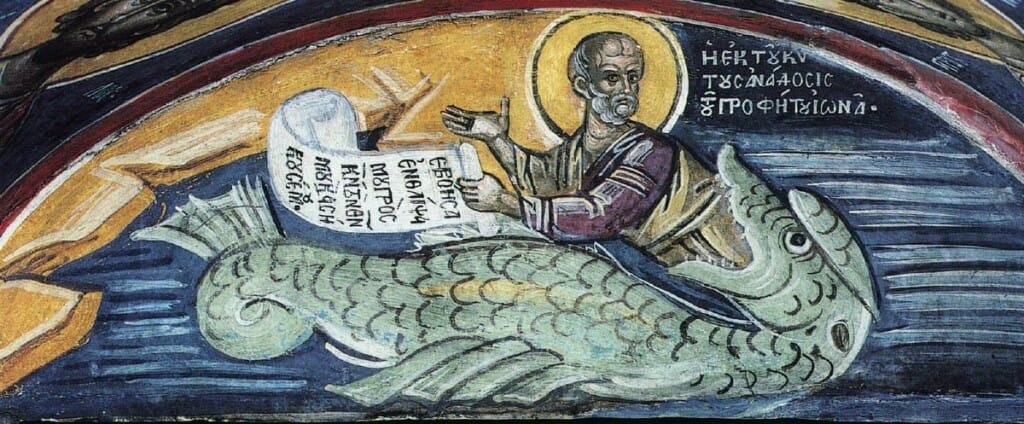

The icon of the Holy Prophet Jonah is one of the the most ancient images of Christianity. Like the story of this prophet, his image is a powerful symbol of death and resurrection. I want to look closely at the story of Jonah and its iconography because it brings together almost all the elements I have been pointing to in my articles for OAJ, elements relating to death and glory, linked closely to the body and to the arts. I have heretofore presented these symbolic elements under a basic leitmotiv, how the paradox of death is a moving away from a center into an always further periphery. I have constantly alluded to the primordial image of the garments of skin added by God to Adam’s nature at the Fall and how they both show his exile from the Garden and protect him within that exile.

The structure of Jonah’s story is based on a few key elements, and most of these have to do with inversion, a surprise or a “switch” happening at the very “end” which turns life into death and death into life. I have explained elsewhere how in our liturgical tradition, Christ’s harrowing of hell is presented as a trick played on Hades, a surprise and inversion where Hades having brought the author of life into death created the opposite effect of what was intended. Like trying to capture light by bringing it into darkness, Christ filled death with life as he entered the pit. With Jonah, one of these switches is of course basic repentance which plays a strong role in the story, but we must be careful not to limit our vision simply to a moral change, because to do so will blind us to some of the more ontological aspects of the “metanoia” which underlies the story.

The very tone of Jonah’s story exemplifies the inversions seen within as it is really the closest thing to a comedy found in the Bible. The comic aspect is not a detail, for as Jonah goes to his extremes he in fact reproduces (or rather anticipates) the movement of Christ down into Hades, then back up and then ascending to Heaven, but he does so almost despite himself, whining and complaining as a parody of the actual meaning. Yet in the story, like a pearl hidden in a shell (or like a prophet hidden in a fish), is Jonah’s prayer, one of the most powerful poetic expressions of death and resurrection found anywhere.

The first sign of the inversion in the text is that God asks Jonah to go East to Nineveh, the Capital city of the Assyrian empire, the current enemy of Israel, but Jonah goes West towards Tarshish to flee God. This is very interesting already, because the West is usually associated with darkness, death and the edge of the world, and this is where he will end up, at the “bottom” of the world. With Jonah asleep in the bottom of the boat, we have the first image of death, of the body and of the arts brought together. Jonah asleep in the bottom of the boat is already his being “dead” yet protected through the water by a “shell”.(1) It is of course an image which refers to Noah, the flood and the animals at the bottom of the ark. This relationship was also made by early Christian artists by linking Jonah to Noah (or even to Daniel) in the catacombs, those caves where the dead were buried.

- Jonah’s fish from the catacombs

- Noah’s ark from the Catacombs

- Daniel in the lion’s den from the catacombs

The pagan foreigners on the boat find out through lots that Jonah is the cause of their suffering such a horrible storm, but when Jonah tells them to throw him in the water, they do not want to do it, they hesitate. This situation is of course a mirror image, an inversion of how Jonah will later be angry that God will not destroy Nineveh, which is the cause of Israel’s suffering. Also, unlike Nineveh which repents before being destroyed because of Jonah’s warning, Jonah does not heed the foreign mariners’ request to invoke his god, so Jonah does not repent until he is “dead”, at the bottom of the water.

Jonah is thrown in the water, and after three days in the fish, the big flip occurs, the great repentance, and we will see the rest of the story like an almost perfect mirror image of the first part. It is very important to notice that Jonah’s fish is traditionally a Sea Monster. The monster, as I have explained elsewhere, is the perfect image of the limit, the place where categories fall apart through a hybridization which is the death of identity and particulars.

- JOnah being vomited by the monster

- Jonah going into the monster

- Paleochristian sarcophagus with the story of Noah

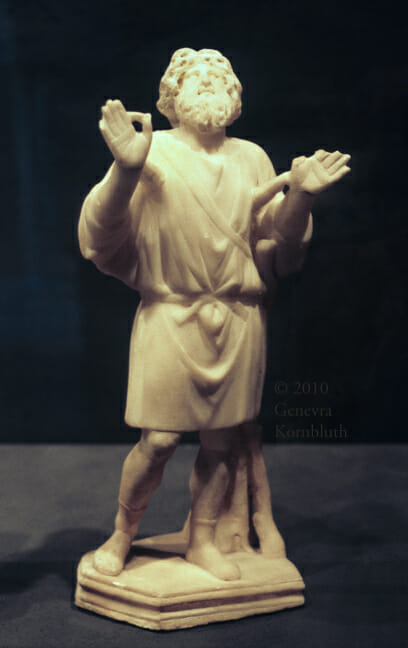

As well as several sarcophagi with the image of Jonah, there are small ivory statues of Jonah dated as early as the 3rd century. In this series of statues, one sees the major elements of the story, Jonah going into the fish, coming out, Jonah praying and Jonah sleeping under the vine.

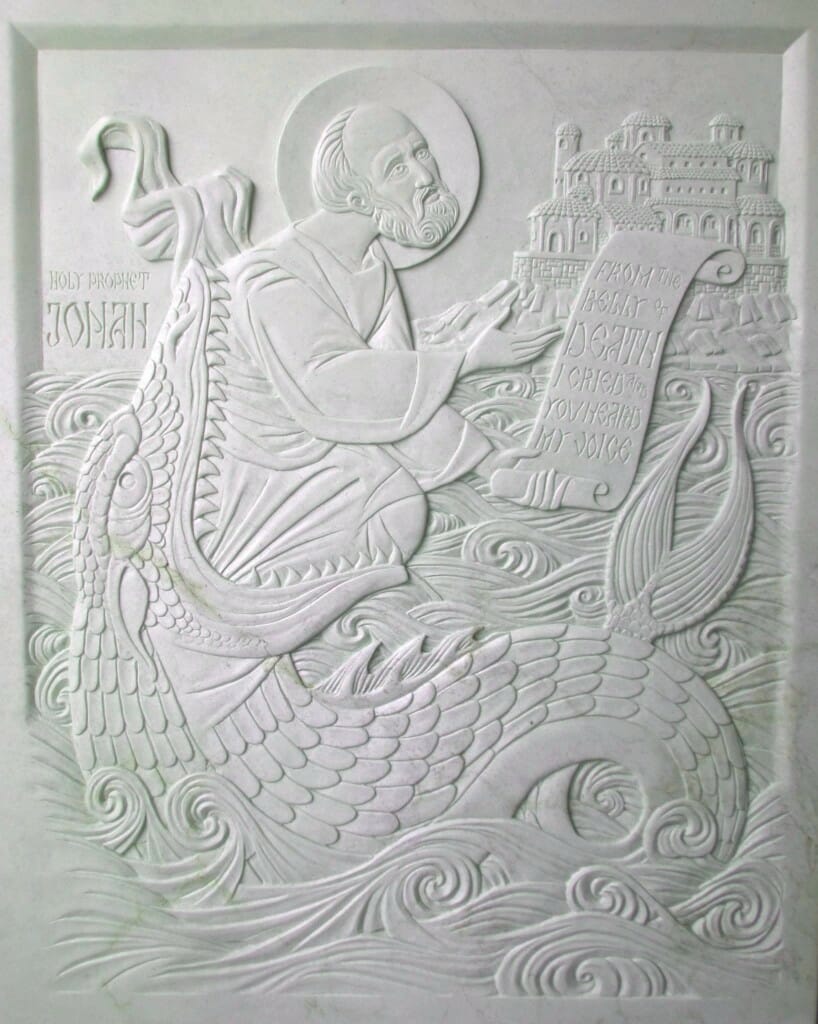

The mouth of the Monster becomes a strong image of Hades in iconography. It appears in Western images of the Harrowing of Hell as well as in later Orthodox images of he Last Judgement or of the Divine Ladder. We need to see these elements as supporting each other in their meaning. So in Jonah’s iconography, the sea-monster is something which has persisted from the very early centuries until now (2).

- Western image of the Harrowing of Hell, 12th century st-Alban’s psalter

- 17th century icon of the Lat Judgement

In the deep, in the bottom of the waters, Jonah utters his prayer. Jonah’s prayer is a powerful bringing together of so many aspects of the Christian symbolism of death and the solution to death. In the first part of the prayer Jonah speaks of his state, of being surrounded by the waters. This surrounding is the very image of periphery for death comes from the outside, the “outer darkness” . He compares death to the “belly” of the fish, to a prison with bars, to a cave or pit, he also speaks of the “lowliness”, of the depths, of his being at the bottom of the world, the root of the mountains. He says that he has been “banished” from the sight of God, and in this he is using the same Hebrew word as Adam and Eve being banished from the Garden. We need to remember that he is using all these images as he has been swallowed by a fish, trapped yet covered by an animal “garment”.

And in that final moment he gives us the solution:

“When my life was ebbing away,

I remembered you, Lord,

and my prayer rose to you,

to your holy temple. (Jonah 2:7)

This is the key, the key to all of it. This is the key to how all human action, all human art and culture can be transformed. It is memory and humility- knowing we are dead and remembering God. As Ilias the Presbiter tells us in the Philokalia:

There is nothing more fearful than the thought of death, or more wonderful than remembrance of God. For the first induces the grief that leads us to salvation, and the second bestows gladness. ‘I remembered God,’ says the prophet, ‘and I rejoiced’ (Ps. 77:3. LXX). And Sirach says: ‘Be mindful of your death and you will not sin’ (Eccles. 7:36). You cannot possess the remembrance of God until you have experienced the astringency of the thought of death.(3)

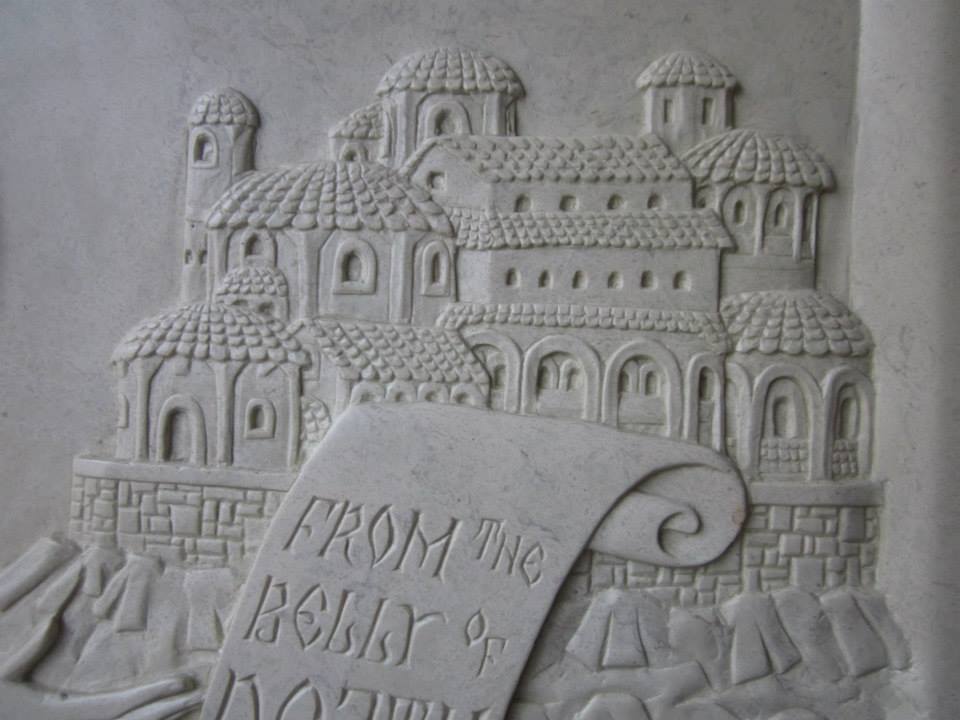

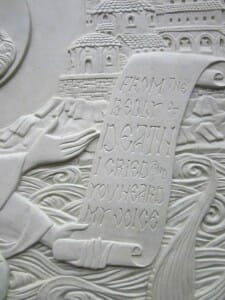

Starting with the Eucharist itself, memory is that attachment to our origin within distance from that origin, it is the link which changes periphery from death into glory. Memory can be expressed as both our remembering God or God remembering us. Just as in the Fish, Jonah remembers God before being ejected from the water, so too in the Ark it is said that God remembered Noah before he was freed from the waters(Gen. 8:1). But just as Ilias the Presbiter tells us, we cannot remember God without the thought or the awareness of death. It is indeed humility, the knowledge of how low we are in relation to God, coupled with our remembering of God which creates the true ontological link between the highest and lowest and which permits us to be transformed. Memory “anchors” us to the Divine Ladder and the level we find ourselves on the ladder does not matter as much as being anchored to it, looking up to God’s “divine Temple”. This is true repentance, and this is what we see Jonah praying, both knowing his death and remembering God, so that when he cries “From the Belly of Death I called upon the Lord”(Jonah 2:2), he could also say: “and my prayer rose to you, to to your holy temple.”(Jonah 2:7)

All of this is also the point of baptism, for baptism is not only dying, a sinking to the bottom of the deep, but in that sinking is operated that double movement which can be summed up in the “Memory of God”, the Memory which operates the inversion between death and glory(4).

As we return to Jonah, we will begin to see how the inversion, the flip which happened at the bottom of the water will begin to play itself out in the rest of the story. Jonah goes East to Nineveh and announces that God will destroy the city in 40 days. The city is made to be yet another image of death for the text gives us the detail that Nineveh takes 3 days to cross, and is therefore analogical to Jonah’s descent into the waters. The city is also made an image of death in two other ways. First it is a foreign city, the city of the enemy, and I have explained in other articles the relationship made in the Bible between the city and the arts with Cain and the foreigner. Secondly, twice the text gives us a very strange detail about animals, in fact this is the only place I know of in the Bible where it is said that animals fast. The fasting of animality is the very image of the conversion of flesh while at the same time continuing the inversion of the story, for unlike the fish that swallowed Jonah the Israelite in the deep, the “foreign animals” fast in the city. Of course God no longer intends to destroy the city once the foreigners have repented, and because the city is made akin to the fish and to Jonah’s tree days, it is almost as if the prayer Jonah made becomes the prayer of the city itself by which it is saved. As I said earlier, the inversion here is that unlike the foreigners in the boat who wanted to save Jonah who would not repent, now Jonah wants God to destroy the foreign city despite the fact that it has repented.

The excess of Jonah is seen powerfully in his now moving out of the city to the East where the inversion of the story will reach its extreme. Jonah was once at the far “West” and now we could say that he has come to the far “East”, instead of being in the bottom of the ship built by men to be protected by the water he is now covered with a plant that God grows next to him so that he is protected from the sun and the wind (read spirit). The moving East and being protected by leaves of a plant is like a kind of rewind of Jonah and Man in general, moving out of the deep pit, through the city and into the garden of Eden where Adam and Eve had made garments of fig leaves to protect themselves.

But those coverings are shown by God to be inadequate, and unlike when Jonah was in the bottom of death and wanted to live, now he is in the glory of the sun and the spirit and wants to die! And this is where God reminds Jonah of the city, of its population and its animals and how God could not destroy such a great city where “they do not know their right from their left”, a very mysterious statement that certainly refers to a kind of innocence in regards to the Tree of Knowledge. And so the city is seen as the “middle” place, not the “naked” facing of God, not the impossible vision of the invisible Father, but rather the glorified body, the Church, the New Jerusalem anchored in the vision of the incarnate Christ. And so this is the hope of human activity, the joy of of the liturgical artist and any artist who wishes to participate through the building of a glorious city, a city that can hopefully both remember death and remember God all at once.

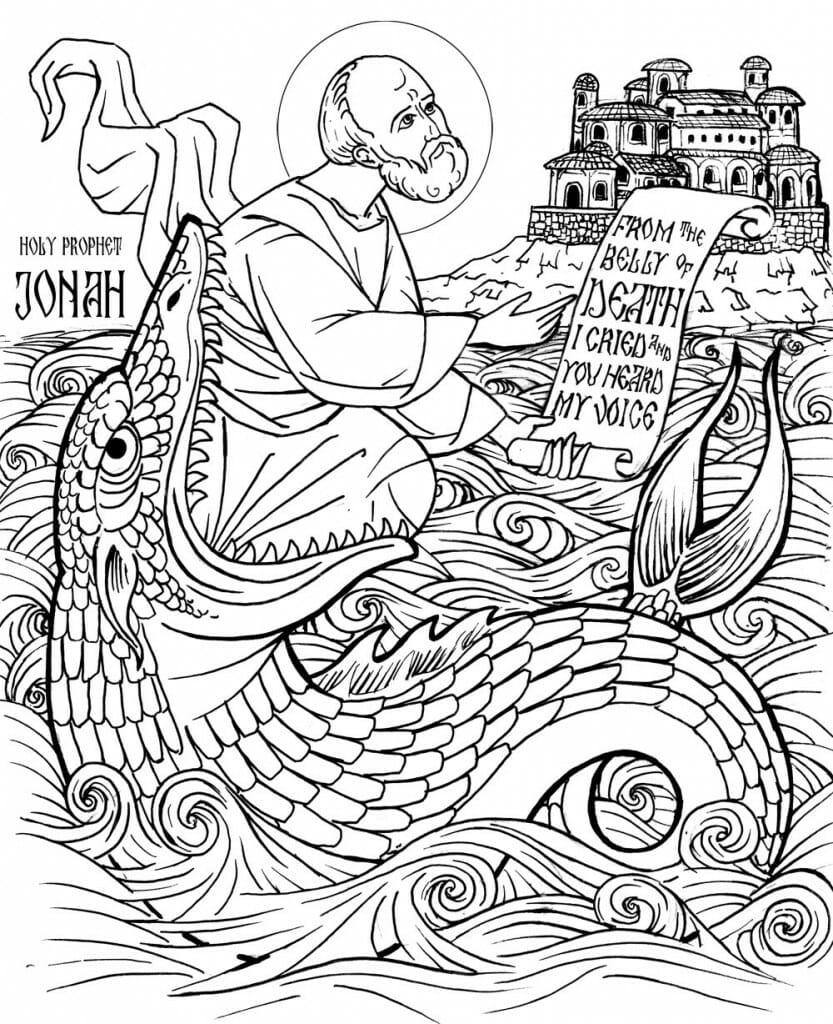

The city often seen in the icon of Jonah is the transformed, saved City and so is an image of the New Jerusalem

___________________________

1. There are many references to Jonah in the New Testament. Besides the comment of Christ promising his resurrection as the “sign of Jonah”, most of the time these reference rather want to oppose or contrast Christ with Jonah. One sees of course in the story of Christ calming the storm the same structure as in the Jonah story, but when Christ rises from his slumber at the bottom of the boat, we see this rising as an image of his power over death by his calming the storm. We see such a contrast again in the story of the walking on water, where Christ is contrasted to St-Peter, Son of Jonah, who cannot by himself dominate death but must rely on his Lord to walk on the waters.

2. Later interpretations try to make Jonah’s fish a “whale”. Of course, though this was attempted in order to make the Jonah story more plausible in regards to modern scientific categories, it is ironic that in doing so it perpetuates the “monster” theme, for a whale is truly a monster. This is true not only because of its gargantuan size, but by the very fact that the whale is a liminal creature, that it can live neither fully out or in water but must constantly “bridge” those two realities.

3. Ilias the Presbyter in the Philokalia, Gnomic Anthology, part 3, section 12

4. In this light, we can see St-Peter’s walking out into the waters we have mentions in note.1 as a microcosm of the history of salvation. St-Peter, like Adam, reaches out to “be like God” and walk on the water, but in doing so he falls, sinks into the deep. Just as Jonah he “remembers” and “calls unto the Lord”, upon which Christ pulls him out and lets St-Peter stand with him above the waters.

Beautiful article! Thank you. I love the way you weave the connections to Adam and Noah as well as your selections of art for the article. The paradoxes, reversals and inversions you walk us through really captured my attention. Very well done – I really enjoyed this piece. And Jonathan, your carved icon… whoa…beautiful and inspiring.

Thank you Michael.

Jonathan, very lovely.

I like that in your composition you used a more intuitive left-to-right composition for Jonah emerging from the mouth of the monster and bringing his prayer/prophecy to the city. This is an improved arrangement compared to the fresco you cite, which has Jonah basically emerging in the center, towards us the viewer. Your monster propels Jonah towards the city while the fresco’s monster is simply being shed off like a skin, leaving Jonah on the beach and recoiling back into the water. I find your composition more meaningful and inspiring.