Similar Posts

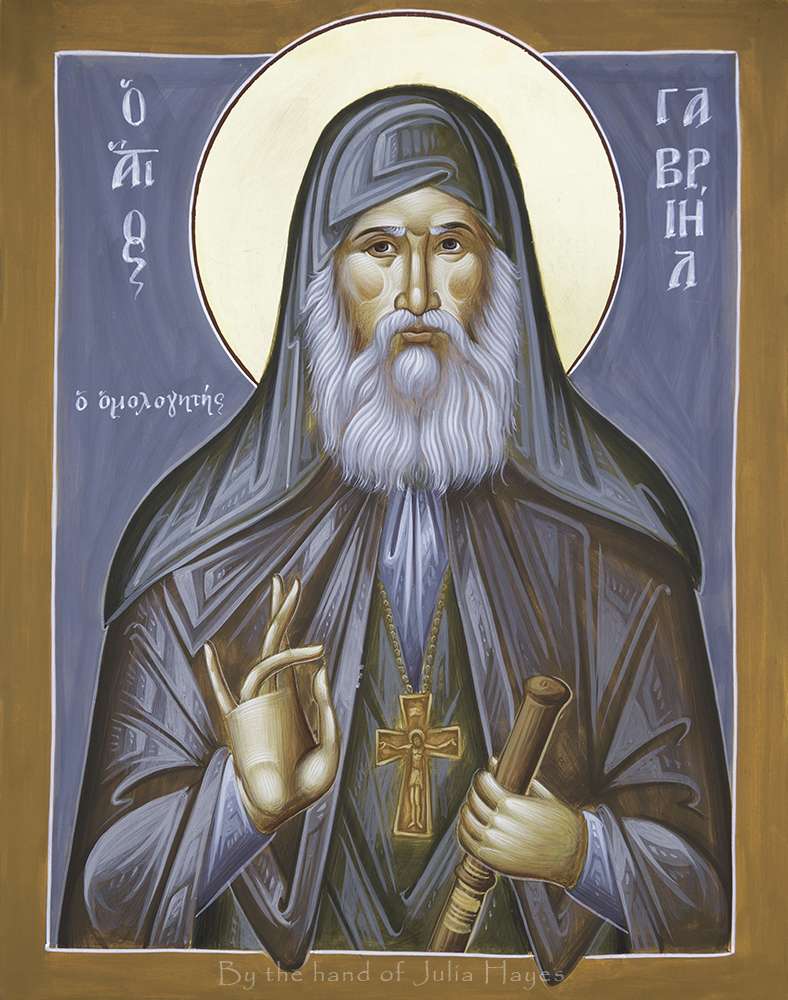

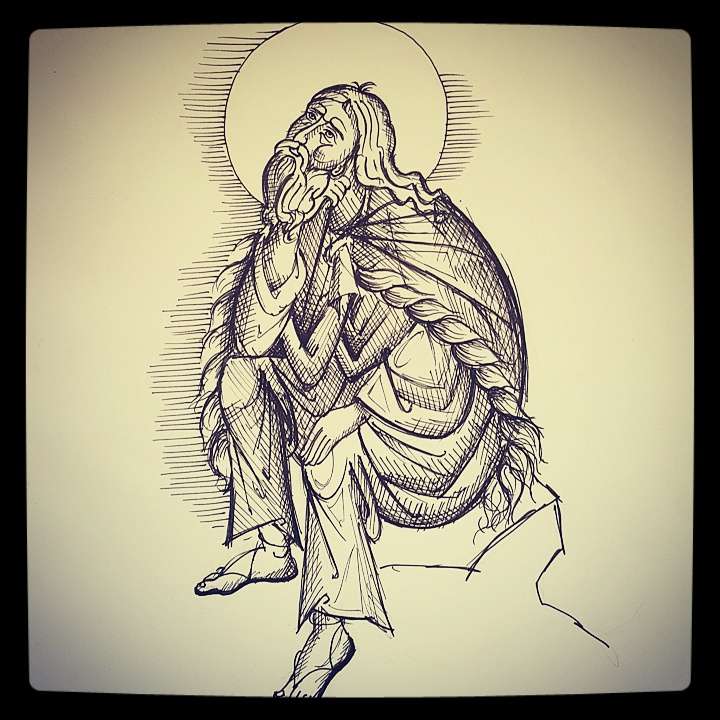

Julia Bridget Hayes is a talented iconographer working in Greece. Her work is a truly wonderful example of creativity within tradition. We asked to interview her and to share these images of her work that she might become better known to our readers.

A. Gould: Julia, you were born in South Africa, but now you work in Greece. Did you discover the Orthodox faith there?

J.B. Hayes: Andrew, I was already Orthodox when I came to Greece. My family was Anglican but we left the Anglican Church back in 1985 and entered the Orthodox Church in 1987. So I’ve been Orthodox for most of my life.

A. Gould: How did you come to live and study there and how did you decide to pursue iconography as a serious vocation.

J.B. Hayes: The thought of coming to Greece and studying here, let alone becoming an iconographer had actually never crossed my mind, and how all those things came about was nothing short of a miracle. I had always drawn since I was a child. When I finished high school I studied photography which was my dream, but during my second year I had to stop my studies for economic reasons. In every spare moment I had I painted and about a year after leaving Photography school, I’d reached rock bottom and didn’t know what to do with my life. In my despair I asked God why I could paint, why it was the thing I do best and what I was meant to do with it. And that is where the adventure began! Just two days later a priest saw something I had drawn and said he’d send me to Greece for 6 months to learn iconography!

It was a year before I eventually arrived in Greece, and during that time I did a lot of soul searching reading up about the Orthodox Faith. And a crazy thought came to me – that I’d like to study theology, but that was impossible. Where and how would a girl from South Africa study Orthodox Theology? I put the idea aside and forgot about it. But nearly a year after the priest had told me he would send me to Greece, he told me once again, but this time he said that I would be going for 5 years…to university… and I had one night to decide what I would study! There was only one thing that I had ever contemplated studying at university – theology! So I came to Greece in 1997 with a bursary and studied theology at the University of Athens. I returned to South Africa for two years where I worked as an iconographer and also presented talks on Orthodox Iconography and did catechetical work. In 2005 I returned to Greece again for post-graduate studies in Liturgics.

A. Gould: What was it like studying with George Kordis? Though your work is quite distinctively your own, I can nevertheless see a lot of Kordis’ influence in it. What do you consider the most important things you have learned from him?

J.B. Hayes: I met George Kordis in 2008 when I was doing post graduate studies at the University of Athens where I attended both his practical classes and some of his theoretical classes on Theology of the Icon and Aesthetics of the Byzantine Icon. He also generously invited me to attend classes at the Centre of Orthodox Icon Painting Studies and Research Eikonourgia, where we were taught by a team of qualified and talented iconographers, led by Kordis himself. Before meeting him I’d had very little formal training in iconography, despite that being the original purpose of my coming to Greece. Due to the pressure of studies, I didn’t have the time to dedicate to learning iconography. I did attend a few lessons at a parish, but they didn’t even teach the basics of sketching. We were just shown the technique for painting an icon in the Cretan style, so I took what I could from there and worked on it myself with the help of books. I also later experimented with the Macedonian style. I had never really been satisfied with the idea of simply making “photocopies” of old icons which is pretty much the standard practice and has unfortunately been dubbed “tradition”, although, in fact it never was the tradition until the 20th century. Throughout the history of Byzantine iconography there was a continual creative development of certain aspects of painting, while others remained unchanged. So studying iconography under Kordis was liberating because he doesn’t simply teach one to mechanically copy old icons. Rather, he teaches the methods and principles of Byzantine painting and the visual theology and logos or rationale that lies behind it, which have remained unchanged despite the numerous stylistic changes that have occurred from one school or period of iconography to another. On the one hand, the way that line and colour function in the icon and the rules of composition and perspective are unchangeable elements, but style, on the other, is something that changes, not only between periods and schools such as the Comnenian period, or the Macedonian and Cretan schools, but also between one iconographer and another. So learning how to use these elements allows the iconographer the freedom to create within tradition.

A. Gould: As a foreigner in Greece, are there any difficulties studying iconography compared to Greek students? Does it give you more freedom, or do people question if your work is ‘Greek’ enough?

J.B. Hayes: I don’t think there are any difficulties, other than perhaps an initial language barrier for someone who doesn’t know Greek. When I first came to Greece the first book I bought was The Technique of Iconography by Ioannis Vranos. I would sit with a dictionary learning Greek and iconography together! Perhaps not being Greek does give me more freedom and in many ways I’m a mixture of many Orthodox traditions. I grew up in the multicultural Orthodox parish of St Nicholas of Japan in South Africa where I was exposed to Russian, Greek, Serbian, Lebanese, Romanian and other Orthodox cultures. I also sang in the choir of the Russian Church in Athens for 13 years, but having lived in Greece for nearly half my life and having a Greek theological education, I do feel more Greek than anything else. No one has ever told me they feel my work isn’t “Greek” enough, but I think that no matter what you do, some people will like it and others won’t, just as some people may prefer the Russian style to the Greek and vice versa. But in general I’ve had a very positive response to my work.

A. Gould: Your work has a style I don’t believe I ever seen before. It combines the lively sketchy brushwork seen in many modern Greek icons with the extreme transparency of medieval Russian icons. I can see how one might see this as the best of both worlds. But it must take great confidence to paint like this – with every brushstroke completely on display, no delicate overpainting to hide it. How did you develop this style, and what are your thoughts on its merits and its relationship to historical work?

J.B. Hayes: My style has developed by combining elements from iconographers I admire or techniques from different schools of iconography. Certainly my drawing style has been influenced by George Kordis and I will occasionally also use his underpainting techniques, but I usually come back to working with a semi-transparent proplasmos. Although others have also compared the transparency in my work to medieval Russian icons, that aspect of my style has been influenced more by the contemporary Athonite iconographer, Fr Loukas of Xenophontos Monastery. I believe that it gives a vitality and luminosity to the icon that I find lacking in icons that are very opaque. I have also been influenced by him in terms of the “sketchy” style of painting the faces in particular, because it helps to create rhythm in the icon. Rhythm is one of the most important aspects of the icon in that it gives the sense of movement that energises the icon and “brings it to life” and into communion with the viewer.

As for whether my style has any merits, perhaps that would be for others to judge. In terms of its relation to historical work, what I strive to do is use the same Byzantine system used throughout all periods and schools of Byzantine painting, that is, the use of line, colour, composition and perspective to create icons that fulfil the ecclesiastical and liturgical function of the icon which is to bring the viewer into communion with the person depicted here and now.

A. Gould: There seems to be something especially fresh and modern about your icons: the cheerful pastel colors, the sketchy illustrative drawing, and the friendly approachable faces on the saints. There is something a little childlike about your icons, in the good and Christian sense, and I like that very much. Do you suppose that we modern people with our distracted spiritual vision benefit from this straightforward simplicity?

J.B. Hayes: Yes, I do think we can benefit from simplicity, as very often we can get lost in the details. And in icons, in particular, often we can get distracted from communing with the person depicted, because of all the details in the icon. St Photios the Great even said that icons should be painted “in manner befitting holiness” and the forms should be purified of all elements of “material indecency and human curiosity”. Even modern Byzantine and Russian icons can become so full of detail, that we lose touch with the person. So I think the immediacy of simplicity allows us to focus.

A. Gould: Tell us about your materials and painting techniques. What pigments and varnishes, do you favor, for instance? Is there anything unusual about how you work with egg tempera to get that dry transparent texture in your painting?

J.B. Hayes: I work in egg tempera, in the ancient Greek tetrachromy, that is, using only four pigments: black, white, terra ercolano (red) and ochre. All the colours can be mixed using just those four and the limited pallet creates chromatic harmony that is often lacking in many modern icons. I usually work on prepared linden wood panels and use a spray varnish. I don’t think there is anything particularly unusual about my technique. I use a fairly dry brush and will paint two or three thing layers of colour to create the proplasmos. Then I build up the layers using diluted and condensed layers of colour, again with an almost dry brush.

A. Gould: It looks like you have done a considerable body of work painting panel icons. Have you had the opportunity to do any mural work in a church? Is this something you’d like to do?

J.B. Hayes: Yes, most of my icons are miniatures. I haven’t yet had the opportunity to do mural work, but I would be interested in doing it on a small scale.

A. Gould: What other plans do you have for the future?

J.B. Hayes: I was once told by a Gerontissa, the Abbess of a monastery, not to plan my future, but to leave it in God’s hands and that has usually worked out for the best. Aside from working on my iconography I hope to finish and publish an Orthodox Catechism I’m working on, God willing.

A. Gould: Can you share your thoughts on the state of iconography in Greece in general? Is really good work in any sense mainstream there, or becoming more so? And do many of the clergy and faithful recognize it when they see it?

J.B. Hayes: I think there is a long was to go before good, creative work becomes mainstream, because the pervasive mentality amongst both clergy and laity is that you either make copies of Panselinos or Theophanis of Crete because that is “tradition”. But I do think a change is beginning to happen here and there are iconographers doing creative work within the Byzantine tradition.

A. Gould: And what about your home country of South Africa? Do you have an interest in developing a South African school of iconography, painting African saints, or anything like that?

J.B. Hayes: I don’t really see myself starting a South African school of iconography. When I was there 11 years ago it was very difficult to work as an iconographer as just getting the basic materials was nearly impossible, but I don’t know if that has changed, and being in Greece hasn’t prevented me from painting African saints. I’ve done a few.

A. Gould: Is there anything else you’d like to share?

J.B. Hayes: I think that it is very important that besides reviving the creative tradition of Byzantine iconography that we also revive the Patristic Theology and Byzantine understanding of the icon. The very people who led us out of the Western captivity of the icon in terms of technique and style led us into the captivity of a modern Western philosophical understanding of the icon. By giving dogmatic and “theological” content to the Byzantine-Russian style and technique of icon painting, something the Church Fathers never did, Florensky, Ouspensky and others, who were highly influenced by the philosophical climate of their time, changed the very definition of the icon. The Byzantine-Russian style became the definition of the icon. If it isn’t painted in this manner, then it is not an icon. This ignores the fact that there are miraculous icons painted in a western naturalistic manner, for example, the Jerusalem icon of the Theotokos that is not-made-by-hands. The style became something that portrays the very essence of the persons depicted, their spirituality, their deified transfigured human nature. This, of course ignores the fact that bad people, like Judas, are depicted in the same manner or the fact that the Byzantine style was also used in secular art. Icons became “windows to heaven” that lead us out of this world and are full of complex symbolism. The very question “What does the icon mean?” is a Western question. All this bears no relation to the Patristic understanding of the icon. For the Fathers the icon is the external form of the hypostasis or person depicted. St Theodore the Studite makes it clear that the icon depicts the hypostasis, not the essence, not his inner being or spiritual state. The purpose of the icon is not to lead us out of this world, but to make Christ and the Saints present with us here and now in our own time and space, the very thing that happens in the Divine Liturgy. This is the liturgical and ecclesiastic function of the icon. Just as the architecture of the Church with the Pantokrator in the dome shows us that “God is with us”, so does the Byzantine icon. The Byzantine technique has no theological or symbolic meaning. Its purpose is through line, colour and rhythm, to make the person depicted present and bring him into communion with the viewer. Byzantine iconography is realistic. The Byzantines would not ask the question “What does it mean?”, but “Who is it?” It’s Christ, and He is in our midst.

Additional work of Julia Bridget Hayes can be found at her website and online gallery.

![MGGlykophilousa[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135909/MGGlykophilousa1.jpg)

![StGerasimosJordan[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135844/StGerasimosJordan1.jpg)

![MGKardiotissa2a[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135905/MGKardiotissa2a1.jpg)

![StXeniaStPb[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135820/StXeniaStPb1.jpg)

![IMGP9678[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135913/IMGP96781.jpg)

![StMosesEthiopian[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135836/StMosesEthiopian1.jpg)

![ICXC5[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135950/ICXC51.jpg)

![StPorphyrios2[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135824/StPorphyrios21.jpg)

![StNicholasMyra4[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135828/StNicholasMyra41.jpg)

![StNicholasAlmaAta[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135832/StNicholasAlmaAta1.jpg)

![StKassiani[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135840/StKassiani1.jpg)

![St Efraim[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135853/St-Efraim1.jpg)

![Prophet Elias[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135901/Prophet-Elias1.jpg)

![ICXCSamaritanWoman[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02135946/ICXCSamaritanWoman1.jpg)

![Dormition (1 of 1)[1]](https://s3.us-east-2.wasabisys.com/media-oaj/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/02140004/Dormition-1-of-11.jpg)

I loved this article and the work is lovely…thank you.

m

Thank you for this article – most inspiring. Please may the BRITISH ASSOCIATION OF ICONOGRAPHERS” include 3 samples of Julia’s work in their Review plus the last paragraph of her interview as this would inspire readers and members of the Association in their icon painting. We would give full acknowledgement as to where this is taken from and may even lead others to subscribe to your valuable web-site.

Look forward to hearing from you.

Commending our Association to your prayer.

Sister Esther

Sister Esther, I don’t mind if you use three icons and the last paragraph, if you don’t mind including a link to my website http://www.ikonographics.net.

Julia

[…] For the last few years our daughter Julia Bridget Hayes has been an ikonographer living in Athens, Greece. Now she has been interviewed by the Orthodox Arts Journal, and explains in her own words how she came to be an ikonographer, and what her work is like An Interview with Iconographer Julia Bridget Hayes – Orthodox Arts Journal: […]

Relevant to the questions being raised in the very last paragraph of the interview:

“We have, therefore, to run counter to mass prejudice, and we must make the holy journey to the heart of the sacred symbols. And we must certainly not disdain them, for they are the descendants and bear the mark of the divine stamps. They are the manifest images of unspeakable and marvelous sights.”

— St Dionysios the Areopagite, Letter 9, To Titus the Hierarch

Forgive me for the delay in responding. I’m very ill at the moment. I will respond when I’m able.

We have to be very careful of applying quotes of Areopagite writings (and other Fathers) that mention “image” and “symbol” to the to the icon, especially when as in the case of this quote he is not talking about icons. To make matters more confusing is the fact that the fathers often use the word “symbol” when they are talking about “signs” and there is a huge difference between the two. A symbol is univocal and refers directly and uniquely to the other object revealing what it is is essence. The bread and wine of the Holy Eucharist are a symbol of the Body and Blood of Christ in that they truly are the Body and Blood of Christ. The Cross on the other hand is a sign. It doesn’t have a univocal meaning but means different things to different people in different circumstances. For the Christian it signifies Christ’s crucifixion, for a non Christian is may just be a decoration. And even if a Christian sees a cross in the context of a maths equation he knows that it is a plus sign and not the Cross of Christ. If we say, for example, that Christ’s red tunic symbolises divinity then red can only be used in that context and no other person (or thing) can be depicted wearing red. The notion of colour symbolism is a western phenomenon that has unfortunately infiltrated into the modern “theology” of the icon. It is completely foreign and contrary to the patristic and Byzantine understanding of the icon. And let us not forget that the 82nd canon of the council of Trullo forbade symbolism.

If we want to understand the Orthodox theology of the icon and the rationale behind the byzantine manner of painting the starting point and criterion has to be the Fathers and Councils who defended and defined what the icon is and the iconography that developed in the period after the iconoclastic controversy. Anything that comes before or after has to be in agreement with them to be Orthodox.

Unfortunately today the “theology” of the icon that dominates in the Orthodox Church is based on a Western understanding of what an image is and how it functions and even the writings of the Fathers are mistakenly interpreted based on these assumptions. Ironically it is based on the same neo-platonic foundation that the iconoclasts used against the icon. The Areopagite writings were highly influential on the Western aesthetics and understanding of the image, but not on the Orthodox understanding of the icon. In the West the image is not a thing in itself but a medium that conveys meanings, ideas, feelings etc it is a symbol that reveals the essence. It answers the question, “What does it mean? This is the complete opposite of the Patristic/Byzantine understanding of the icon. The icon quite simply *shows* the external form of the person depicted. It does not reveal his sanctity, his transfiguration or some otherworldly reality. It simply shows (but does not describe) the person. When a byzantine saw an icon he wouldn’t ask “what does it mean?” but “who is it?”, “what is it?”. It is Christ, it is Peter, it is the nativity. This blunt reality of the byzantine icon is very difficult if not almost impossible for western minds to comprehend so they keep trying to create hidden layers of meaning that aren’t there.

The modern theology of the icon was created in opposition to western art but is founded on the neoplatonic and romantic assumptions of Western art . The Byzantine icon did not develop in opposition to Western art, and therefore needs to be understood in its own terms.

Julia, first I want to say that I appreciate your work very much, your icons are beautiful and lively and there is much warmth in the execution. I was happy to see them and read your interview for OAJ. I have to say though that a few of your pronouncements, especially those regarding Ouspenski and Kontoglou and this last comment to the quote by St Dionysios the Areopagite are difficult for some of us to understand.

The distinctions you make between concepts like “sign” and “symbol” seem difficult to follow and I struggle to understand where you get them from, especially when you say that one means the other in the Fathers at certain places that seem to disagree with your point. It seems also when you attribute an arbitrary or relativistic meaning to a cross rather than what you call ‘univocity’ that such an interpretation does not hold. A cross always has the same meaning at its base which is its very form, that is a union of a vertical and a horizontal line forming a central point, all subsequent meanings derive from this. In Christianity, the fullness of this symbol was revealed, that is the union of heaven and earth through the death of the incarnate Logos.

In my own research, I have found that the Byzantines were in fact quite interested in meaning and they even believed the material used to create an object participated in its meaning. I have written an article in which I quote many Byzantine poets relating the meaning of steatite which they called the “spotless stone” to icons of the Mother of God. There are also poems where the green color of the stone is used to make elaborate references to the Mother of God as a meadow out of which plants grow.

It is difficult to understand what you mean when stating that icons only “show” the external form of a saint and do not reveal the sanctity or do not have meaning in them. It seems like the iconographic convention of the halo is there precisely to show the holiness of the person depicted. And there are so many iconographic conventions that obviously have meaning, especially when we are aware that they are not simply a showing of a person or an event. For example, Christ never wore a Roman clavus. He or the Apostles didn’t carry a book or a scroll with them. Martyrs never walked around with crosses in their hands. It seems even more difficult to say that festal icons don’t have meaning and are just a “showing” of an event. I am certain the Byzantines knew that St-Paul was not at the Ascension or Pentecost or that there was not an old bearded man with a crown in the door during Pentecost. These inclusions in icons not only produce a “what?” but also produce a “why?”. Why is St-Paul in those icons? Why does Cosmos have scrolls in a cloth? It seems normal that the Byzantines didn’t go about “explaining” icons the way we do simply because they knew what they meant, it was the internal language of their culture. They knew it in a very deep, implicit and possibly non-discursive way, the same way we don’t have to explain a hand-shake or a necktie or an emoji icon because these are internal parts of our own culture. We just use them without asking questions. But to say that a hand-shake or an emoji “have no meaning” does not seem reasonable.

Everything in Creation has meaning, has a “logos”, has a reason for its existence or else it would not exist. This this is my reading of St-Maximos… It is possible that that the “reason” is implicit or unknown, or some people may even give erroneous or limited explanations of that meaning does, but this does not imply that meaning is not there.

Of course we both agree that Byzantine icon did not develop in opposition to Western art. Yet despite this, we do live in the context of Western art and so we cannot pretend to live in 8th century Constantinople. That is we can agree with the Fathers of the icons and also see that other formulations can be added when the need arises. Orthodoxy did not develop in opposition to Arianism, to Nestorianism, to Iconoclasm or any other challenge to itself, but once that challenge happened it had to explicitly answer it and that answer became an integral part of its external definitions. That is what “modern theology of icons” does, it answers the challenge of western/modern visions of art which viewed icons as primitive and naïvely misunderstood reproductions of visual reality. Because Western art has been so pervasive since the 17th century, The visual and iconological cues of icons are no longer the internal language of our culture. To approach them today, we NEED to start by attempting to point to their meanings, defend their style, their pictorial rules. Do we do it perfectly? No. Can we be corrected? Yes. Are there a large number of silly things said in the process? Certainly. It seems that attempting to brush modern theology of icons aside for a “pure” rediscovery of so called Patristic understanding is impossible and is rather akin to Evangelicals who ignore their own innovations with a call to Biblical purity.

I understand you want to emphasize “encounter”, a direct experience of a person through their image, I get it and there is definitely value in such an approach. Icons include this element. But what is difficult is that your point is formulated on an attack on meaning in icons, and this shows that once again we are opposing phenomenological approach of the icon to a structuralism approach (two modern visions of epistemology). We are playing out the same meaning war that has plagued the modern world for the last centuries. And in the end this is what is most difficult, that what could be a worthwhile emphasis on some particular aspects of the icon ends up creating heated resistance by the need oppose it to others.

Such exquisite work – a most interesting interview.

Try as I might, I cannot mix any color approaching the blue you obtain using only black and white. Are there particular black and white pigments you use and recommend?

Thank you for your help, and for sharing your incredible work!

John

John, the black and white will only appear as blue in contrast with warm tones. If you just mix black and white on a white background, it will appear grey, but once you start painting the warmer tones, it will appear blue! It’s like magic! It should work with any black, but I use iron oxide black.

[…] An Interview With Iconographer Julia Bridget Hayes […]