Similar Posts

One of the exciting aspects of the renewal in icon carving we have seen in the last few decades is how this renewal is in a constant dialogue with painted icons. One of the visible goals, one of my own goals, is a search to infuse into the carved image some of the visual aspects of great painted icons. How to render clothing, hands, noses, eyes, mouths in a way that evokes the balanced hieratic and classical beauty of the best icons without betraying the carved medium? I recently had the chance to copy a famous icon of St-Anne and the Theotokos and so I thought I would take the reader through my decision making process in adapting it.

The original icon was painted in the 17th century by Emmanuel Tzanes, a Cretan iconographer who worked mostly from Venice. The painted image is rather striking, for example in its joining of a bold transcendent appearance of St-Anne with the soft gesture offered by the Theotokos as she holds up a lily. Another aspect I have always loved of this icon is the delicate way St-Anne holds her child, and how the folds of the Holy Virgin’s clothing are pulled back slightly by the touch. This is something I wanted to make apparent. Also, I wanted to capture the intensity of St-Anne’s stare, but soften it a bit, and the same for the Theotokos. I wanted to add a touch of tenderness in their expression.

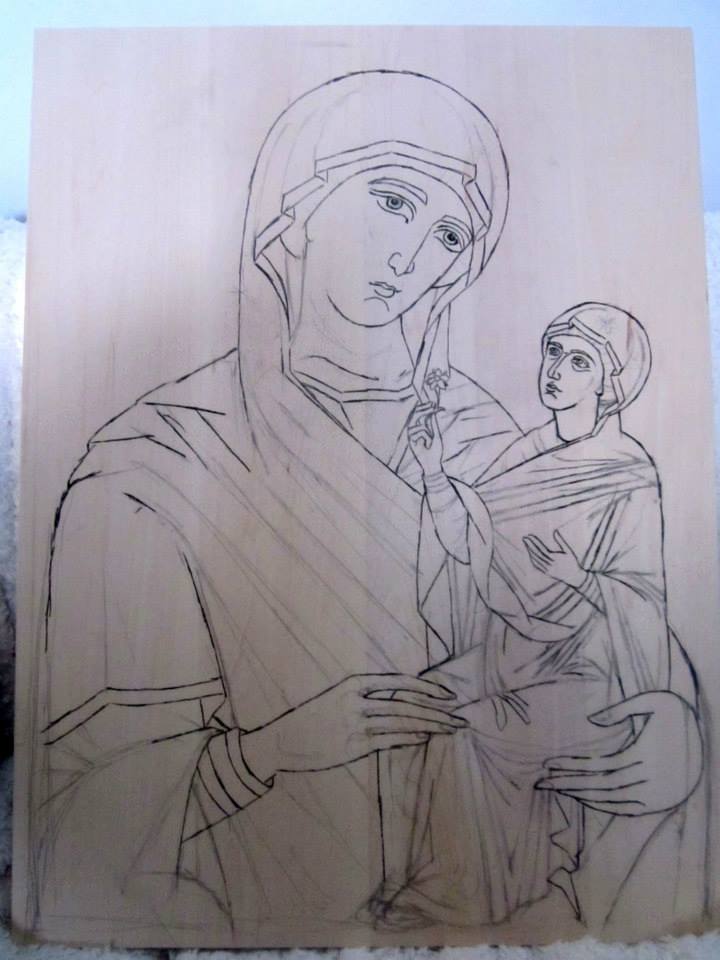

Drawing

In the drawing, one can see already many of the decisions I was going to make. The faces are softer. I also worked out the clothing. In the reproduction of the original, it is difficult to see some of the clothing, much of it is also quite abstract. I organized a basic structure with what I could see. But my drawing for the clothing will change as I come to the actual carving.

Depth

I usually carve quite shallow, but because of the boldness of the image and size of the carving, I decided to make it much deeper. Despite this, I didn’t want to have a excessively deep border and so the entire border of the carving is slanted when you look at it from the side, that is the lower part is thicker than the top part. The figures are actually protruding from the border , it becomes “high-relief”, something which never happens in my usual carvings. In this I wanted to capture a bit some of the later Russian high relief icons which use this technique.

Clothing

Clothing in Byzantine style iconography grew highly abstract in succeeding centuries. What in the 10th century were reinterpreted classical forms became far more stylized by the 17th century. We see this in Tzanes’ icon, where folds are concerned with streaking light and lines across the figure, something which is very beautiful, but loses its efficacy when done in carving.

What I usually try to do is find some balance. I interpret the drawing by balancing it out with influence from the well-worked out clothing of 10th-11th century Constantinople ivories. I tell every icon carver who asks me for advice to look intently at these images, for they work out the folds with both a great “physical” logic of movement and iconographic abstraction.

One of the aspects of the 10th-11th century style is that it avoids using parallel lines in clothing. This is also a rule I try to follow because parallel lines in carvings just look like stiff “bars”. And so even if in the drawing I did of the Theotokos I kept some of the parallel lines form Tzanes’ icon, in the final carving these were nearly all broken up and rounded out.

I also decided to add the detail of the St-Anne’s veil being draped between her arms. Without this it seemed as though the lines of her garment were “dropping” out, and the veil is a powerful way to visually hold the image in the frame. It is near impossible to see what was there in the original icon from the reproduction I had.

Faces

Just like in clothing, there are many later Byzantine practices regarding faces which are very difficult to render in carving, especially the way light is used.

In the Tzanes icon, there is a high level of abstraction in the light, which swerves from the cheek to move under the eye, or there are lines streaking on the the forehead or on the side of the nose. These uses of light are immensely beautiful and show us in visible form a hint of uncreated transfiguring light. This is something which when attempted in carving, gives strange shapes and gouges.

Russian attempt to create these abstract lines in a carving. Because this is St-John the Forerunner, it is strangely appropriate and gives a stern, rough expression, but I would not attempt this on a youth or a woman.

I also made some changes to the face, rounding out the chin, changing the shape of the nose, adding a subtle smile and bringing in a curve at the eye socket where in Tzanes it is almost a straight line.

Conclusion

Carving is a medium that has its own reality, its own visual and tactile presence. Just as in the painted icon, the subtle play of shades and levels intertwining, meeting and coming apart can be a powerful vehicle for the sacred. I always say that in North America we have many obstacles to our Orthodox faith, but being less tied to cultural identity we also have an opportunity. I believe our approach to icon carving can seek its inspiration in the best painted and carved icons. Through a synthetic approach, we can look to our entire Tradition, pulling the best from Byzantine, Russian, Georgian, Coptic and Medieval Western imagery, thoughtfully and prayerfully looking for ways to make Christ and his Saints present to the modern world through their carved image.

Thank you, Jonathan, for this very interesting side-by-side comparison. It’s great how you recognize the limitations of carving, and thus leave out certain things that can only be painted. But you also recognize the potential strengths of a wood carving, and add a tenderness and femininity that is usually lacking in Byzantine icons. The result is very successful indeed.