Similar Posts

Many thanks to Mary Lowell for initiating a discussion of American Orthodox terminology – especially the problematic phrase “to write an icon.” Her article describes the technical problems with this translation very clearly, while acknowledging its appeal to many English speakers.

I have a slightly different perspective on this matter. I am an intensely visual person. I like to look at pictures or make them all day long, but am exhausted by reading, writing, or talking. I am unusual in that I find visual art richer and more meaningful than books or poems. When I read the news, what I really want to see is a press photo, as it tells the story to me better than the written words.

I know that this is unusual because I observe a bias towards text all around me. People would say “read an icon as though it is visual text.” But they would not say “look at a book as though it as textual picture”. Why not? The two statements are equally sensible, or equally absurd. (In fact, though, we do occasionally say the latter. I have heard people say, for instance, that a certain magazine article about some country “paints a picture of a society rife with poverty and corruption”. This phrase makes a lot of sense to me, as it accurately reflects the strength of pictures, which is that they show a lot all at once, in contrast to the weakness of text, which is that it says only one thing at a time.)

In reality, of course, we do not need to refer to one thing as another in order to understand that it has content and meaning. Pictures and texts each convey meaning in their own way. Each is equally capable of manifesting truth or lies. People seem to have forgotten this. Nowadays, written text is still universally understood to hold specific objective meaning, whereas many people treat visual images as though the content (and the beauty) is merely in the eye of the beholder.

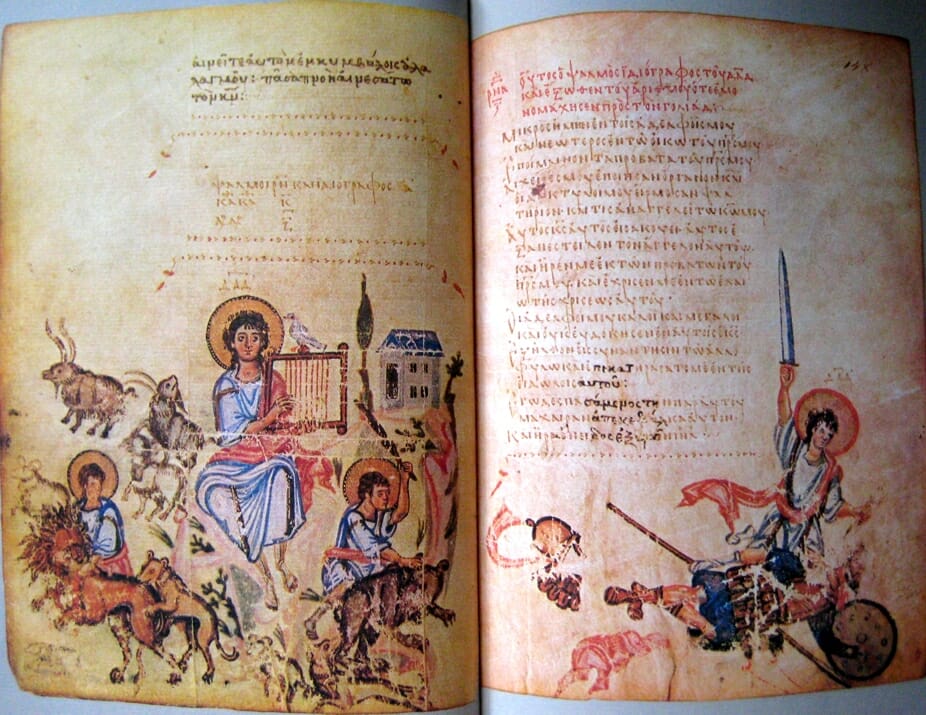

In the Middle Ages, the arts of writing and picture-making were treated with real balance. The Church valued written scriptures and painted icons equally. Illuminated books contained both in equal measure. There was even recognition that icons had a special honor in that they could be understood by all, whereas only the educated could read books. Hence icons held great importance even to the Russian state. They were on the banners that led armies into battle, and on the kremlin gates to show the authority of the czar. Written texts could not wield such power over the masses in those days.

Today, the situation is quite different. Almost everyone can read, and the arts of writing are practiced with a high level of professionalism and in quantities never before dreamed of. Visual art, on the other hand, has decayed. Professional visual artists either hide in the esoteric world of modern gallery art, or serve prosaic ends for the merchants and media. Our culture almost wholly lacks profound visual art that moves the hearts and minds of the people. This is probably one reason that our society has developed a bias in which we believe text to convey meaning better than pictures.

Another reason has to do with modern academia. In the Middle Ages, academics were expected to be proficient in all arts and sciences. Educated men could draw, paint, compose music, interpret the stars, as well as read and write. An ancient university was a creative paradise in which the arts worked together to express all human knowledge of Earth of Heaven. Modern academia has lost this. Through the influence of the so-called Enlightenment and of 19th-century professionalism, the visual arts have been demoted and the study of letters has been exalted.

This bias is especially true in our seminaries. Men who become priests are mostly men who like to read, who can stand to learn ancient Greek, and who have a memory to quote scripture. Like most academic degrees, the Master of Divinity is designed for those who learn through words. A visual person likely would find it tedious in the extreme. The accreditors would hardly be pleased if a student asked to pass his exams by drawing pictures instead of writing essays!

It was in this textually biased atmosphere that the modern field of Iconology arose. Iconology is talking about icons, not painting them. It is a way of deconstructing icons and reducing them to words. In the hands of iconologists, an icon is a semiotic puzzle to be taken apart, reduced to figures, colors, and props. Each component is a symbol, a stand-in for a word, and the icon can be translated into its textual meaning. Iconology does serve a useful purpose – it is a way of introducing icons to the visually blind. It shows modern people who are not accustomed to meaningful images that there is in fact, meaning in images. Ultimately, it provides an academic framework for studying icons in a way that can be reduced to essay questions on an exam – an absolute requirement in modern universities. (After all, the obvious way to test seminarians on the knowledge of icons would simply be to ask them to draw them! But such a test would not suit academia).

It is not surprising then, that seminaries find the idea of ‘reading and writing’ icons appealing. In fact, probably most Americans find it attractive. It particularly appeals to converts from Protestantism. After all, Protestantism has always been rife with a text bias mixed with iconoclasm; if you say it’s written and not painted, then it’s not quite so much like the Catholic paintings that you always feared as a protestant. Of course, some people are attracted to Orthodoxy for more exotic reasons – the mysticism of Eastern religion, for instance. The term will appeal to them as well, because it implies gnostic secrets locked into the icons – an ancient language accessible only to the iniated.

I believe that all these affectations are ultimately harmful. Iconography was not contrived as an academic or mystical image-language. When Byzantine iconography arose, it was the natural style of painting used for all purposes in late Rome. It was as immediate and accessible to all people as cell-phone photos are to people today. We should not play up the exoticism or sophistication of icons. To do so may seem to exalt them in a romantic or academic sort of way, but in fact, it undermines their effectiveness as liturgical art. We should emphasize that icons are straightforward portraits of holy people and biblical events, painted in a way that makes them immediately accessible to our hearts and minds during prayer. If modern people have a hard time looking at them clearly, then we do not need to deconstruct the icons (and we certainly don’t need to replace them with a new style of painting) – rather, we need to teach people to see truth in beautiful images the way everyone once could. This is a matter of changing our culture, and it is not something that can be taught in school. A sensitivity to beauty can be acquired only by exposure to beauty. The church can gradually teach modern people to see by surrounding them with intense beauty, until the beauty of good icons and the truth of God’s kingdom become inseparable in our hearts and memories.

Before ending, I wish to address one very specific way in which the text-biased study of icons has been harmful. It has enabled a vast number of badly painted icons. The notion of ‘writing’ an icon has led many artistically inept people to attempt to make them. If icons are just a language of symbols, then anyone who can learn the language ought to be able to ‘write’ them. And so, we have had several decades now where people with some theological knowledge go and take a weekend class in ‘icon writing’, and declare themselves iconographers. After all, it’s pretty easy to copy the colors and robes and inscriptions in the prototype. What else is there to do? Well, there is the problem of making them beautiful paintings. This is not taught at the weekend workshops. It requires a lifetime of study and a good bit of artistic intuition. Only a talented student apprenticed for years to a master has any real hope of becoming an icon painter. But the idea of being an ‘icon writer’ – that is much more alluring, as it seems so easy, yet so sophisticated. And the opaque awkward icons that result will be immediately accepted by priests and converts the church over, because they too have learned to see icons by ‘reading’ them rather than by gazing upon their beauty.

I sincerely feel that the Orthodox Church has a serious problem with blindness to art (and also deafness to music – but that is another story). We benefit greatly from the cultural inheritance we received from the Middle Ages, but almost none among us can even imitate it, let alone build upon it. For the most part, churches are indifferent to beauty. They want things to ‘look Byzantine’, but will accept the worst imitations of Byzantine art as though an ugly icon or an ugly church is no worse than a bible printed in an ugly font – a minor technicality compared to the real meaning of the thing. The term “write an icon” is a symptom of this imbalance. The term itself is problematic, but the blindness that makes it attractive is a grave sickness for a church as ‘visual’ as ours.

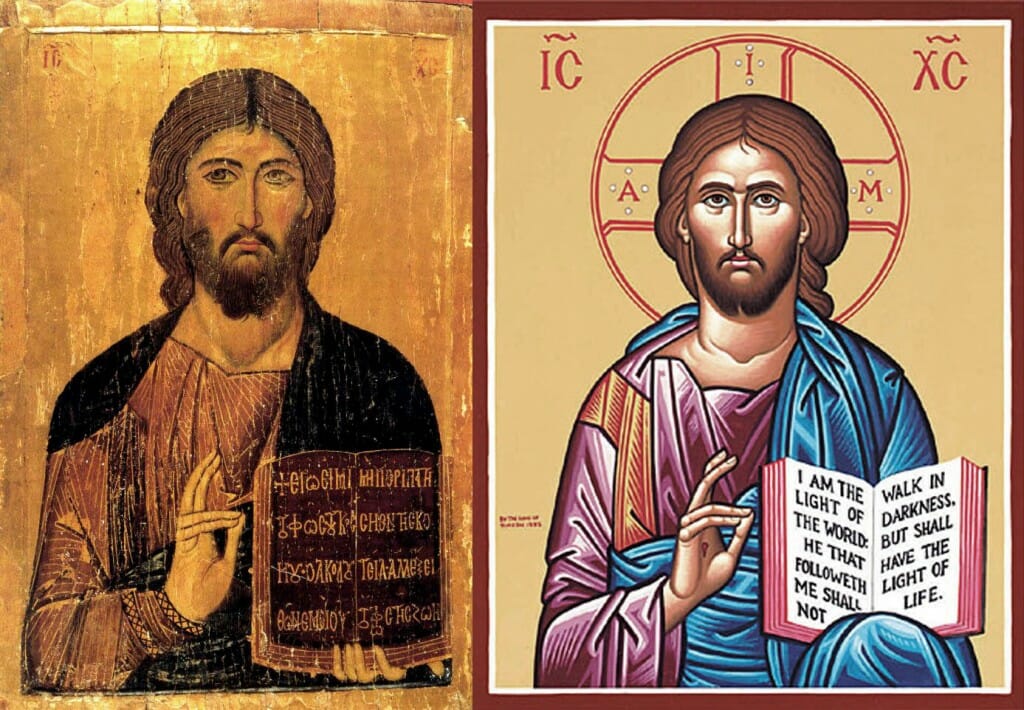

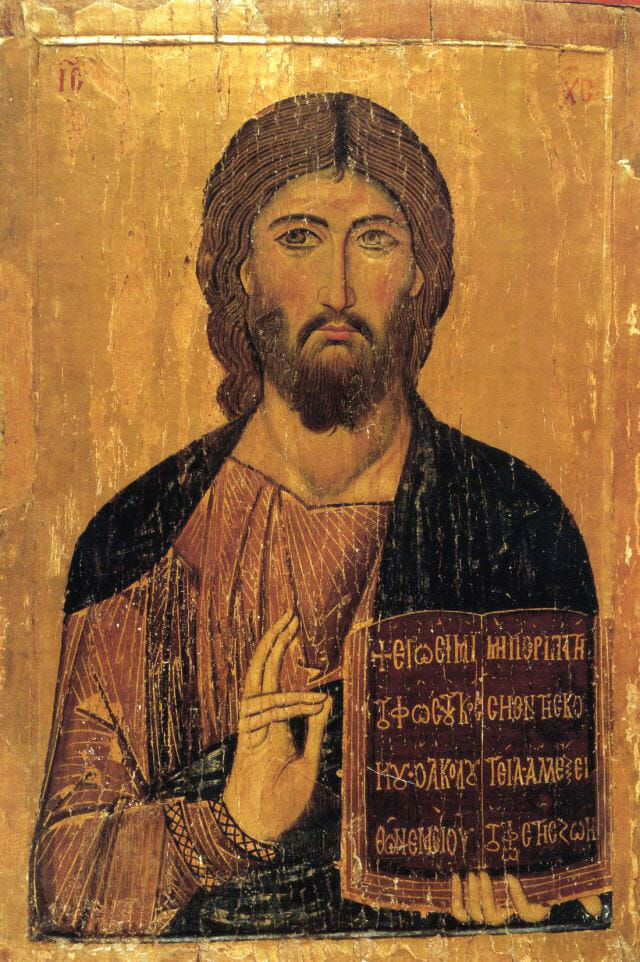

A Byzantine Christ Pantocrator juxtaposed with an example in the simplistic opaque style frequently practiced nowadays. Can anyone really not see the difference here? One is a portrait that breathes the very life and soul of Christ Himself, as though He were standing before us in the flesh. The other is nothing more than a hieratic symbol of Christ, as cold and lifeless as a plastic figurine. But an iconologist might say that the modern icon is correct, because the colors and inscriptions follow the ‘language’ of the canonical prototypes.

i find reading icons fascinating and feel “writing” an icon is an appropriate term to use! when you know how to read them, you can learn all about them. the colors of the robes denote the temperament and their spiritual leanings. which fingers are raised or what they are holding tell us something else. the curls in the hair, the styling of the beard…all are clues as to the nature of the saint depicted and tell us far more than the naming alone does.

the process of writing an icon, even after only a weekend class, is not about what it looks like when completed, and frankly some of my favorite ancient icons are “poorly” rendered in terms of artistic merit. it is a process of deep meditation and prayer for the person writing the icon, with the goal to be about “letting go and letting God”. truly, this deeply prayerful practice can be as life changing as the person who might have a deep meditation practice, for example. it is the action of doing it, not the focus on making it “beautiful” that it is all about, in my opinion.

also, these are not in any way supposed to be portraits of the people meant to really look like them. the well rendered ones are based upon the golden ratio, and can be measured in their lay out, including the placement of eyes and nose. special compasses for spacing everything properly can and should be used when making “new” icons so they are done properly. most people’s faces are not so perfectly aligned mathematically, proportioned specifically.

as to the difference in these two icons you have pictured here, one is egg tempera and one is acrylic. please, no offense to anyone, but many of us don’t consider acrylic icons to be true icons. when written in the traditional methods, with each step of the way being prescribed, the final outcome is much richer and much more beautiful, no matter the skill level, sort of the difference between watercolors and magic marker. when i took my three iconography classes, the focus was on the symbolism of each step of the writing of the icon… the making of the board, the laying of the cloth and the rest, and how this is a reflection of God, our relationship to him, etc. While these teachings may or may not have been traditionally taught, the reflection on all of these teaching with each icon I write at every step of the way transforms MY experience from one of just painting to one of deep prayer and meditation.

this is my limited understanding, but i am know there are others out there who are much better schooled in all of this than i am that can correct me.

Dear Marcee – It is good that the process of iconological analysis has helped you to understand the meaning of icons. I acknowledge that iconology is a useful discipline because modern people do not always intuitively understand Byzantine paintings the way ancient people could.

Nevertheless, understanding the symbolic language of icons is only the beginning of really understanding how to paint them. The technical aspects of pigments and layers and fluid expressive brushstrokes are what differentiates a good icon from a poor one, and these things take many years of serious study to master. So ultimately, I do believe there is far more ‘painting’ that goes into making an icon, than there is anything that could be called ‘writing’.

Also, I feel compelled to point out that your notion of icon making as primarily a personal meditative discipline is not traditional. It sounds like you consider icon making to be a kind of art therapy. Perhaps it is therapeutic for you, and if so, best of luck with that. But this is not the concern of the church. To the church, iconography is liturgical art, and what matters is that the icons are edifying to those who look upon them in church, not to those who paint them in the workshop. Traditionally, it is considered appropriate to begin icon painting with a prayer, and maybe pray during pauses between steps. But to meditate during actual painting is not conducive to a high level of craftsmanship, and has not historically been part of the tradition (though I am aware that some will claim otherwise).

You’re right that acrylic paint is somewhat problematic for icon painting, but this is really a minor and purely technical issue. It is certainly easier to paint beautiful transparent colors using mineral pigments and egg tempera than it is using off-the-shelf acrylics. But some iconographers have managed to paint rather good icons in acrylics, and many have managed to paint very bad ones in tempera. I would discourage any attempt to mysticise egg tempera as some sort of holy medium that is canonically required. After all, ancient icons were made in wax, mosaic, fresco, carved stone, cast metal – anything the artists found to be physically suitable.

True enough with your comparison of images, but isn’t that a Monastery Icons “icon” on the right?

Richard I had the exact same thought when I looked at the two icons… the one on the right surely seems like one from Monastery Icons…which to me aren’t icons… the one from Daphni is beautiful. The other is very soul-less….

Thank you, Andrew, for taking the discussion to another level. As an administrator for an ecclesial art school, I have seen first hand, over and over again, what you mean here, though I cannot entirely agree on the cause: “The notion of ‘writing’ an icon has led many artistically inept people to attempt to make them. If icons are just a language of symbols, then anyone who can learn the language ought to be able to ‘write’ them. And so, we have had several decades now where people with some theological knowledge go and take a weekend class in ‘icon writing’, and declare themselves iconographers.”

I not convinced that the terminology is the primary cause of so many “badly painted icons” or their happy reception. I do think that it amounts to a general “blindness” to beauty in American (possibly all modern) culture, as you say. Badly painted icons are only symptomatic, but tragically self-perpetuating; persons with little talent or “artistic intuition” look at examples of “badly painted icons” and think quite rightly – “I can do that.”

Unfortunately, badly painted icons get an extra pass, a big kings X, because of their “byzantine” quaintness. I’m not sure that iconology lingo has that much to do with it. The weekender takes home the trophy and basks in the praises of family, friends and priest. The “new” iconographer receives commissions, only furthering his or her delusion and increasing the blindness of the recipients.

As you say, “It requires a lifetime of study and a good bit of artistic intuition. Only a talented student apprenticed for years to a master has any real hope of becoming an icon painter.”

At the same time, many long-standing practitioners with impressive pedigrees have spoiled church interiors for generations to come. Sadly, many of these spoilers could have greatly benefited from legitimate apprenticeships at the outset of their careers, and perhaps even been dissuaded from the pursuit all together. For years I have thought to myself “Thank God, another success story!” when a student says something like “I’m afraid icon painting just isn’t for me”. Icon painting is a demanding calling that takes many years to see see its fruit; it is not a hobby. We have done our job if we can help people figure out which applies.

“Unfortunately, badly painted icons get an extra pass, a big kings X, because of their ‘byzantine’ quaintness.”

I’ll go a step further and suggest that badly painted icons (along with badly composed and badly sung liturgical music) get an extra pass BECAUSE they are badly done, and are thus considered to be more “spiritual”. Cute little pious stories like St. George saying he didn’t hear anything when the monks who sing badly brought in a guest chanter for his feast day ( http://www.antiochian.org/node/22680 ) only reinforce this.

Anti-intellectualism is a cancer in society in general and the Orthodox Church in particular. It saddens me to see the efforts of generations of our spiritual ancestors, many of them among the finest artists, composers, poets, and musicians in their day, so readily cast aside due to ignorance. I call upon others to stand up against the status quo of mediocrity that prevails throughout our church institutions and preserve the integrity of our spiritual heritage before it disappears completely, especially when it is inconvenient to do so.

This discussion as many other on-going discussions, which I have only today had the blessing to have witnessed on this website, is, in my view, at the very centre of the Theology of our Holy Church. To those who have offered their views here I am very grateful and I can appreciate (I think) in each instance what “pain” has brought forth the comments here made. It is not that I find myself agreeing with everything here said, quite on the contrary and in several instances, but for the first time in a very very long time, I am witnessing the right sort of questions being addressed in the midst of a broader chaos of aesthetic singularisation, relativism and deconstruction taking place everywhere around us and which is also naturally affecting the ethics and criteria of the flock of Christ for what it is to depict and convey meaning which is of essence, logos,(such as the holy icons) and what this is to beauty.

I would like to make a few comments to suggest where Andrew Gould’s thesis, though absolutely felt in every living cell of my heart, and while it has also been part of my own small trials and exercises to somehow express (though never completely) that which is of God’s Holiness and unsurpassable beauty, may also find difficulty in finding fullness.

People of theory shall theorise. Many of them unwisely choose to touch on those things which they have never had personal experience with. Their talk and writings are lifeless as are often the art produced (especially that which is mass-produced as well) through the processes they imply. This, I feel, is Andrew’s frustration as is to everyone who is a true artist who has strived to produce true beauty through his or her work. This, the superficial reading of an art-work, is very often the case for art-historians and especially those who wish to speak of the Holy Icons. But, as very potently stated or implied, we do not have “art” in Church. We have devotion and love to Christ, we have liturgical life, ascribed to all things, and offered unto Him in all things. I think however that there is a fine parameter to this act of offering that we must, in addition, consider seeing as what we are interested in is not mannerism.

We have a great tradition in what one may call “canonical” liturgical iconography, fully employing techniques, symbolism, synthesis, precedents, skill and proper proportion. This is the liturgical art that we often like to imitate with all the gradations of effort, the richness of poetic meaning and interpretation and of course necessitating profound persistence and great talent, often captured in these works. However, there are also many icons that are far from canonical, not performed by the rarely gifted artists, often very disproportionate, sometimes shocking in the their simplicity, but which quite incredibly, because they were performed with tears, heartfelt prayer and devotion, these are icons through which Christ has deemed worthy that they should become profound channels of Grace and bear the signs of the Heavenly Kingdom in this world of affliction, death and sin. These are the miracle working icons: they bear myrrh, they bleed or weep it times of distress, they speak, they shine with the uncreated light of Christ. We do not know why, they do not look like great icons from an artistic perspective on first inspection, but what is clear is that they have something unique on them, which reveals a quality which is often, in fact most often, very difficult to describe or perceive because it demands our other eyes (those affording spiritual vision) to be employed in addition to our physical eyes. We come to the Holy Icons to receive consolation, find a bridge to the uncreated Glory of God, we come to weep for those in affliction and our own mistakes, we ask for mercy and we give thanks for all things.

If I may therefore, I will add this. I think perhaps, I may be wrong, that a humble and contrite heart, learned in the faith of the Holy Orthodox Church and the Holy Tradition, which shall bring man to utter a word, to verse a poem, to draw a line or do anything out of genuine devotion and love to our Lord, that heart which has received Christ, not only has the ability to transcend the realm of what we call canonical, or properly artistic, but also most often will reveal something new (usually ever so subtle) of the Glory of God. This other beauty, for those who are able to appreciate it, is often abundant in the older icons that we see. The reason is simple. These icons, were really and truly, objects of great devotion, requiring profound effort to be completed sometimes. The materials, the techniques, the mode of life of the iconographers, all these things demanded a great amount of preparation and sacrifice. Paints were not abundant, neither were tools, teachers were rare and the places where one could practice the holy discipline were very often remote. When the many hundreds of thousands of Greeks of Asia Minor were forcefully displaced in 1922 by the Turks, the first objects they took with them were the Holy Icons. They were the most precious things they had. All things in the Church are provided and made to lead us to Christ. Icons both in the making and as employed in worship as our mediators to the saints, the All Holy Theotokos and Christ himself ought to be considered as such. Made to the Glory of God, and offering us a foreshadowing of the Kingdom of God, made manifest at present, through those who have ascended to union with Christ in this life.

Thank you, Archdeacon Spyridon, for your very thoughtful comments. Indeed the matter of miracle-working icons is a difficult one. Certainly there is no particular correspondence between miracle-working icons and artistically great icons. But also, I see no reason to believe that miracle working icons are particularly likely to be those that were made with exceptional love or faith on the part of the maker.(Especially considering that some modern printed icons that were ‘painted’ by an ink-jet printer have become miracle-working).

So, to my mind, miracle-working icons are a holy mystery. God alone knows why some icons are granted such grace. Perhaps it is completely misleading for us to imagine that it has anything to do with the icon itself, as opposed to God’s purposes for working miracles in a certain community at a certain time.

Ultimately, I do not think the rare and exceptional instances of miracle-working icons should dominate the discussion of icon-painting. The main purpose of icons is as an aid to prayer for those who look upon them. The quality of icons should be judged based upon how well they serve this basic liturgical function.

I agree, by the way, that old icons of a folkish or amateurish character are absolutely wonderful. I do not consider them to be lacking in beauty at all. Even when they have awkward proportions or sloppy details, they still have harmonious colors and loving expressions. The unfortunate icons painted by amateurs nowadays (usually in garish opaque acrylics) are a completely different matter. They are not the product of a poor society trying its best, but rather they are the product of a rich society not trying very hard at all.

“They are not the product of a poor society trying its best, but rather they are the product of a rich society not trying very hard at all.”

Wow. You have said a lot right there, and it applies to a great many weak efforts characteristic of our rich society. That sentence alone should be enough to make us all retreat in silence to contemplate our complicity in this wave of self-satisfied mediocrity.

Nothing in God’s providence may be attributed to chance or is ever unrelated to our relationship/devotion to God (or lack of it).

“Let every thing that hath breath praise the Lord… Praise ye him, sun and moon: praise him, all ye stars of light. Praise him, ye heavens of heavens, and ye waters that be above the heavens. Let them praise the name of the LORD: for he commanded, and they were created. Praise the LORD from the earth, ye dragons, and all deeps: Fire, and hail; snow, and vapours; stormy wind fulfilling his word: Mountains, and all hills; fruitful trees, and all cedars: Beasts, and all cattle; creeping things, and flying fowl; Kings of the earth, and all people; princes, and all judges of the earth.” (from the Book of Psalms)

Everyone of course recognises that Mystery is not equivalent to chance, nor can the acts of devotion be limited to hand-made items. If we agree that icons are first and foremost objects of devotion (otherwise we are most certainly intellectualising unsuitably) then how can we ever say that the devotion in making them is unrelated to the result they display or in fact the way in which God chooses to utilise them for our enlightenment, cure and salvation (which is why miracles performed through God happen)? Agreed, our processes do not necessitate that an icon will become popularly known as wonder-working, but to posit that our means of work through devotion, prayer and fasting in obedience are unrelated to it becoming one is needlessly cynical and, forgive me, false. The wonders worked through icons can be an expression either of our faith and love towards the sacred person there depicted but may also be worked through grace bestowed upon the iconographer (from the words of Elder Epiphanios Theodoropoulos, a greatly revered hieromonk in Greece of great ascetic struggle, who slept in 1989, who makes mention to the wonders worked through the holy icons).

Miracles (though we should preferably use the word used in original New Testament Scripture: semeia i.e. signs which signify the presence of God) such as the ones we see related to holy icons can of course be seen in other instances where devotional objects are not icons. Garments and handkerchiefs of the apostles would perform miracles (Acts, 19:12). Recent examples of such comparable signs of Grace would be in the remains of churches, the old garments of saints, objects related to them, crosses, prayer ropes, vestments. See the many miracles related to St Nektarios, St Raphael in Mytilene, St Matrona the wonderworker, St Loukas of Crimea the holy doctor and bishop, the late elder Porphyrios (now a saint!). Thankfully, we do not control where God chooses to make His presence or His reality especially felt and this indeed is a mystery.

But we know this: God shall make His presence felt through his Holy ones i.e. those who live in repentance and devotion to God. The ascetic practice of iconography is indeed an act of devotion and prayer and ought not to be regarded as artistic engagement alone, regardless of whether it is a weekend long or a lifetime practice. Asserting that devotion to Christ is unrelated to the act of icon-making or that miracles related to icons have little to do with the process of their making or indeed the devotion paid to the saint there depicted, implies that so long as we follow “rules” (i.e. a process of making or painting alone), and regardless of our inner state of being everything is fine. This may dangerously assimilate to what, by poetic permission, one may call aesthetic “pharisaism”… How can you touch upon the life and figure of a saint, elevated to Communion with the Deity, if you are spiritually lost and destitute? How can you write a truly beautiful prayer or sermon if you are not devoted entirely to Christ? The fathers of the church spent many years in prayer, often as hermits, before being able to compose the philokalic writings which form the sacred patristic heritage of the Church. The three hierarchs St John Chrysostom, Gregorios the Theologian and Basil the Great, had top formal education, but spent years in the desert before being able to bear spiritual fruit and offer the tools for the expression of Theology in the Church. Our elder Sophrony Sakharov of Essex, of blessed memory, abandoned his most beloved practice of painting for many years, drawn to spiritual exercise and obedience before then returning to iconography towards the end of his life. But when he returned, his art was alive with the Holy Spirit imbued with Grace and the experience of the uncreated Light.

I am not suggesting that we are all able to take on the spiritual struggle of these giants of the Church of Christ, but we can at least be humbled by our lacking in depth, and take precedent from their life of devotion to do as much as we also can in our lives.

We must be cautious that we are not drawing a dangerous trend towards stylising (byzantine or otherwise) these devotional objects regardless of “the-maker-in-prayer” as a parameter. The point in not to show off our “great talent” in the church, painting in the colours and styles of the great predecessors who became pens, brushes and batons of the Holy Spirit. Ok, so we made a beautiful copy. Ok, so we just read the prayer. Ok, so we followed the steps… The question is did you live the experience of that icon, that prayer, that path? If we are stuck to the reproduction of “art”, without allowing the longing for God’s Light to reach our inner most depths and transfigure our heart, then this is almost completely losing the point (even though we all must start somewhere).

One may stylise through ignorance, arrogance, stupidity and oversimplification and one may also do so by means of pride and foul investment of faith in their human ability and talent. Neither mannerisms however, neither daft nor proud (one could easily swap the adjectives to either end), produce fruit or “work” eucharistically i.e. devotionally and thus do not lead to Christ.

“Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.”(Cor 13:1)

Suppose that we acquire such robotic technology (which no doubt very soon will be available) such that we could imitate the dexterity of a profound painter, then it would be indifferent whether icons were made by robots or men… is this what we want? Is a dextrous, lifeless robot imitating our movements equivalent to a living person fashioned to become a temple of the Holy Spirit devoting his heart and hand gestures in prayer and concentration in order for Christ’s holy saints to be imprinted on his or her heart and then on the canvas? I think not.

Thus, to make things clear, it is not that miracles ought to dominate the icon-making process or its result. But devotion to Christ, this definitely should. And I think anyone will agree, that mediocrity first and foremost can be measured by means of devotion both with regards to the artistic effort required but also in connexion with the spiritual striving demanded. The wonders worked through icons are a reminder of their true purpose and the fact that we ought not become deterministic or too eclectic about the artistic criteria for these both can and at times ought to be superseded by new or alternative means. Look for example at the Archangel of Mantamado in Mytilene, fashioned out of the blood of the martyred monks of the monastery. The aesthetics of the Cross, these ought to pervade our being so that we can make truly beautiful and honest art. This includes the way we address their purpose. It is one thing to say that they are mere aids for prayer and it is a different thing to call them the Triumphant Living Theology of the Church.

I forgot to say happy new year to everyone! Many years to all! Thank you once more Andrew for this beautiful webpage!

Excellent & insightful article! I am writing my doctoral thesis on icons & will site this.

Perhaps a little etymology of the greek word -graphy could help the author of this article! Look up -graphy at Dictionary.comword-forming element meaning “process of writing or recording” or “a from Greek -graphia “description of,” from graphein “write, express by written characters,” earlier “to draw, represent by lines drawn,” originally “to scrape, scratch” (on clay tablets with a stylus)

So, graphia originally related to both pictures/glyphs/lines both used for drawing and writing. The problem is always IN TRANSLATION. This is the reason the Greeks still use Greek in the Divine Liturgy. It’s like sacrileage to go from the original to the watered down version in translation. So much is lost!

Luckily, I just posted this: https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/from-logos-to-graph-lost-in-translation/

I typed a very long and (I thought) interesting reflection on your essay (which I heartily agree with by the way), but sadly it’s now lost due to a problem with the little password protection thing above. Oh well! Now you’ll never know my amazing thoughts because I’m not retyping them. 🙂

Your discussion of iconology reminded me of the comment made popular by Elvis Costello (but which apparently is of earlier origin): “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.”

To my simple mind, an Icon tells a story through the medium of painted images. Because it tells a story, it is a “writing” using paint.

The following quote is from the Homily 17 of St. Photios the Great (This homily. If memory serves me right, was delivered on Holy Saturday Morning after the Platytera icon had been revealed having been plastered over for nearly a century by the barbaric hands of the iconoclasts).

“The Virgin is holding the Creator in her arms as an infant. Who is there who would not marvel, more from the sight of it than from the report, at the magnitude of the mystery, and would not rise up to laud the ineffable condescension that surpasses all words? For even if the one introduces the other, yet the comprehension that comes about through sight is shown in very fact to be far superior to the learning that penetrates through the ears. Has a man lent his ear to a story? Has his intelligence visualized and drawn to itself what he has heard? Then, after judging it with sober attention, he deposits it in his memory. No less – indeed much greater – is the power of sight. For surely, having somehow through the outpouring and effluence of the optical rays touched and seen encompassed the object, it too sends the essence of the thing seen on to the mind, letting it be conveyed from there to the memory for the concentration of unfailing knowledge.”

You can find the homily in full at http://synaxisstudy.blogspot.com/2012/02/homily-17-saint-photios-great.html

In Christ,

Fr. Micah

[…] some of my own insight. In reading both Mary Lowell’s first piece as well as Andrew Gould’s answer, it is difficult not to see how there is much bubbling under the surface of this conversation. In […]