Similar Posts

Editor’s Note: This open letter was written in response to Philip Davydov’s call for master iconographers to address some fundamental questions about their art and its relationship to the Church.

Dear Philip, thank you for the interesting article.

It seems to me that the questions you have presented to us are not that difficult to answer: every iconographer who practiced our art long enough has had to answer them at least once. I would try to offer my perspective.

Every time people talk about canonicity, asking “Is this style canonical? What is the canon?” and the like, what they are actually trying to ask is this: Is this icon acceptable for church use? Can it be blessed? Does this image correctly express our faith?

These inquiries should lead us to two most important questions which are truly worth asking:

- What is an icon?

- Why do we need it?

There are different answers to these questions, which subsequently define the appearance of icons.

I believe that: 1. Iconography is an Art, not a pious craft and 2. This art offers itself into the service of the Church. Ergo, all discussions about “canonicity” that ignore ecclesiology as an essential part of this art are fruitless.

Interestingly enough, Dn. Alexey Trunin made an important statement during the presentation, answering the question “Who can be a judge for your icons? Me and me alone!” It is this attitude, which coincidentally no longer works, even in secular art, that led to the destruction of three of his projects – all of which were quite well done artistically, in my opinion.

For example, his last mural project in St. Nicholas Church (SPB), which was destroyed most recently:

- Was paid for by a large corporation outside of the parish.

- Had the iconographer chosen by the architect (who himself was selected by the same corporation), and

- Had the final order for destruction issued by the metropolitan.

All decisionmakers were outside of the parish! I doubt that the parishioners had any input in the selection process (or in the decision to destroy the murals) at all. Most of those who were trying to protect murals were also not members of the parish.

In order to place the situation in the proper context for American readers: in most Russian churches (except a few rare cases), people do not form close-knit communities at all – the very same communities which should support parish activities and have an opinion about church matters.

From my experience, this situation would never arise in an American church, mostly because the Church here is organized in a different way – and I know many examples to support this claim. When members of the local church community delegate representatives into their Building Committee, they normally trust the decision of these representatives, and share responsibility for the success of the project. Obviously, such an approach would not permit a radical project to be started, but if some parish appreciated the work of Dn. Alexey Trunin and chose him as their iconographer – this project would never be destroyed.

Another thing that caught my attention – in the beginning of his presentation, Dn. Alexey Trunin claims that his approach is “to depict the world through a pure child’s gaze”- as you present it in one of your questions, and in the following discussion he indicated that “only those who have professional education could appreciate this work”.

Frankly, I see this as problematic. Look at all these carefully crafted compositions, reflexes, complimentary colors – they reveal years of hard work and study to refine artistic skills. There is nothing truly “naïve” in his painting. I can only wish that my children would be able to see a world in this way without any education. While I personally can enjoy this kind of painting, the question still remains: will this work help people in that particular parish become closer to God?

And the answer to this would bring us to subsequent questions: Why do we need icons? Does an icon tell us something which cannot be expressed in any other way? Should an icon express the knowledge about God, which Church as whole possesses, or be only an expression of the artist’s inner self?

Mind you, I’m not saying that artistic expression in iconography should be limited by rigid sets of rules, but only that artistic personality should not be in first place. In addition, such an approach should give a clear purpose to our effort to become better.

You are absolutely right – there is no “iconographic canon” if it is comprehended as a codex of rules to follow – Glory be to God! Some people may try to re-define canons in terms of a “precedent” or “following a prototype” – this approach is better, since we have about 2,000 years of tradition, but it is still not enough.

I would offer a broader definition: the icon can be called canonical, if it is accepted by the Church, represented by the local community, sacramentally expressing such acceptance in the act of blessing of the icon.

Now, to your other questions: Yes, the icon is created for prayer, but one should not limit the meaning of prayer by the “request” only. The prayer is communion: being in presence of God is a prayer too. I think we all agree that if the icon “speaks” to you, it works.

Icons could be different for different people – and yes, the icon in academic style is definitely an icon. Look, for example, at the Our Lady of Sitka icon, painted by famous Russian court painter Borovikovsky. The same is true for “contemporary elements in icon”- as long as it speaks to you and does not obscure correct teaching of the Church. At the same time, the image of the Holy Trinity created in the style (and composition) of Rublev, but with FOUR figures is not.

For me, representation of our time is never the main goal. Our time will inevitably reveal itself in my work if I try to be obedient to God, honest with myself, and involved with the local community for which I create the work.

And finally, I agree with you that the moderator of your presentation was correct: the book of Ouspensky seems totally outdated (and not only for a younger generation – the late Ksenia Pokrovskaya and I discussed this in 2001 at her seminar in Boston), and today there is a need for a New Theology of iconography. I would hope it includes an ecclesiological dimension of icons – and I don’t think it would limit creativity in any way, as you, perhaps, are afraid.

Another topic we had discussed at that seminar in Boston is, surprisingly, related to the questions presented today. Is iconography an Art or a pious (sacred) craft? The craft was described as a process of following a set of rules, which, if followed correctly, will, automatically, lead to a successful result. Since this approach is easy to replicate, this, of course, becomes the curriculum in both advanced schools of iconography and “6-days-learn-all” type of travelling classes.

If such teaching is used only as a tool to learn how to organize the process of painting in a more effective way, I have nothing against it. However, if these sets of rules are proclaimed as “The Only Canonical Way to create icons”, or even worse, when a deep spiritual meaning is assigned (always post-factum) to every technical step, this becomes a problem. This, and various “symbolic explanations of colors”, along with unceasing attempts to copy historical monuments in contemporary buildings without taking architectural context into consideration, can create an issue.

In our time, when even artistic production in contemporary art becomes conceptualization, it is understandable. I, once again, completely agree with you – it denigrates the art of iconography to only a pious craft – with signs or symbols which are so fun to de-code.

There is only one remedy for that – the education of people, iconographers, and hierarchy.

And I think that your seminar and our discussions of these questions is a small step in the right direction.

Vladimir Grygorenko

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

Thank you, Vladimir, for your thoughts, and in particular for providing the photos and backstory regarding Dcn. Alexis’ controversial murals. I’m quite interested to see them. Though I wouldn’t find these murals a great fit for every church, they seem very well suited to this one. The architecture of the church, though good, is somewhat harsh and modern-influenced. Indeed, it probably needs to be, considering the aggressive modern context of its surroundings. It’s a good balance between tradition and context. The murals seem to wrestle successfully with the very same challenge. (Honestly, I would find it somewhat traumatic to worship with Rublev-style icons, and then immediately walk out the door and see that building across the street). I’m not surprised the architect chose Dcn. Alexis as the painter.

Admittedly, Dcn. Alexis’ work lacks the easy prettiness that many people like in icons – but I’ve seen so many examples that are far more radical or harsh than this, and yet attract little commentary (the murals in our own St. Vladimir’s Seminary chapel, for instance). When I read that a metropolitan had ordered murals to be destroyed, I expected to see artworks far more difficult. That it was these murals that were so controversial indicates much about the contemporary Russian Church.

Dear Vladimir,

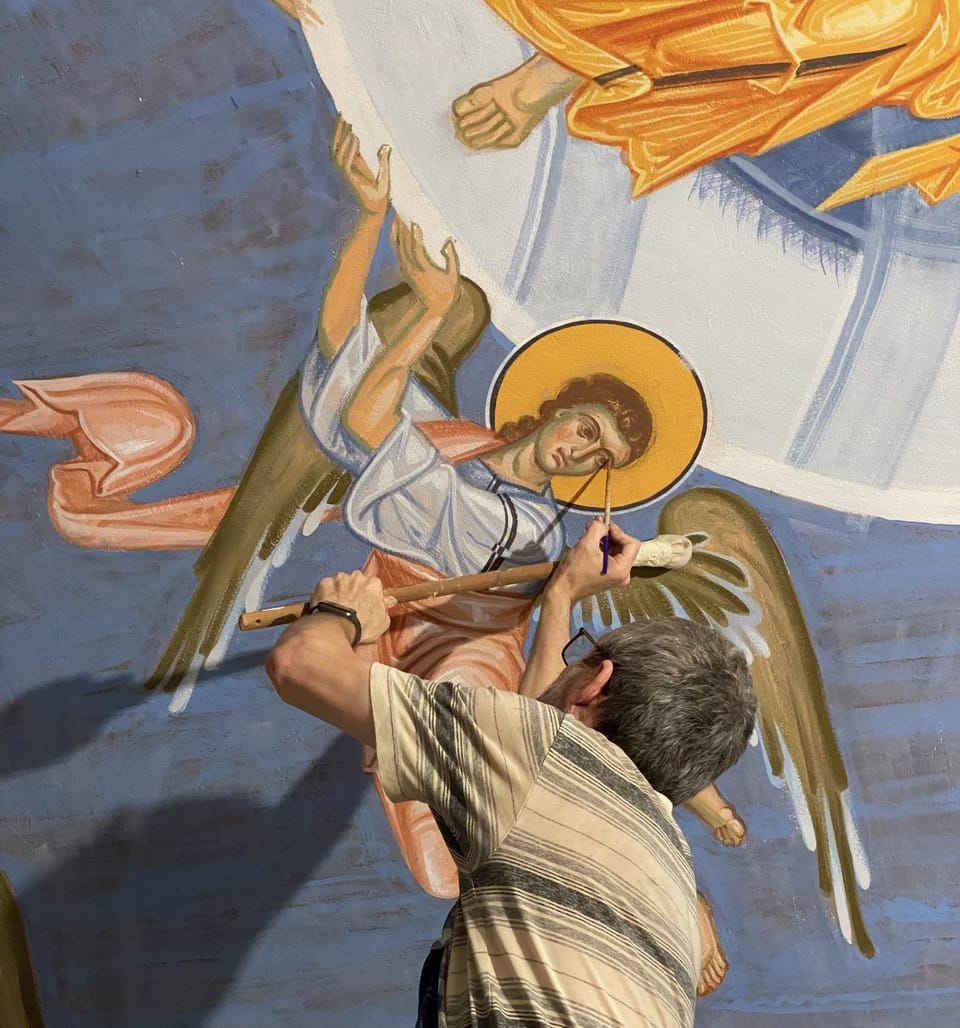

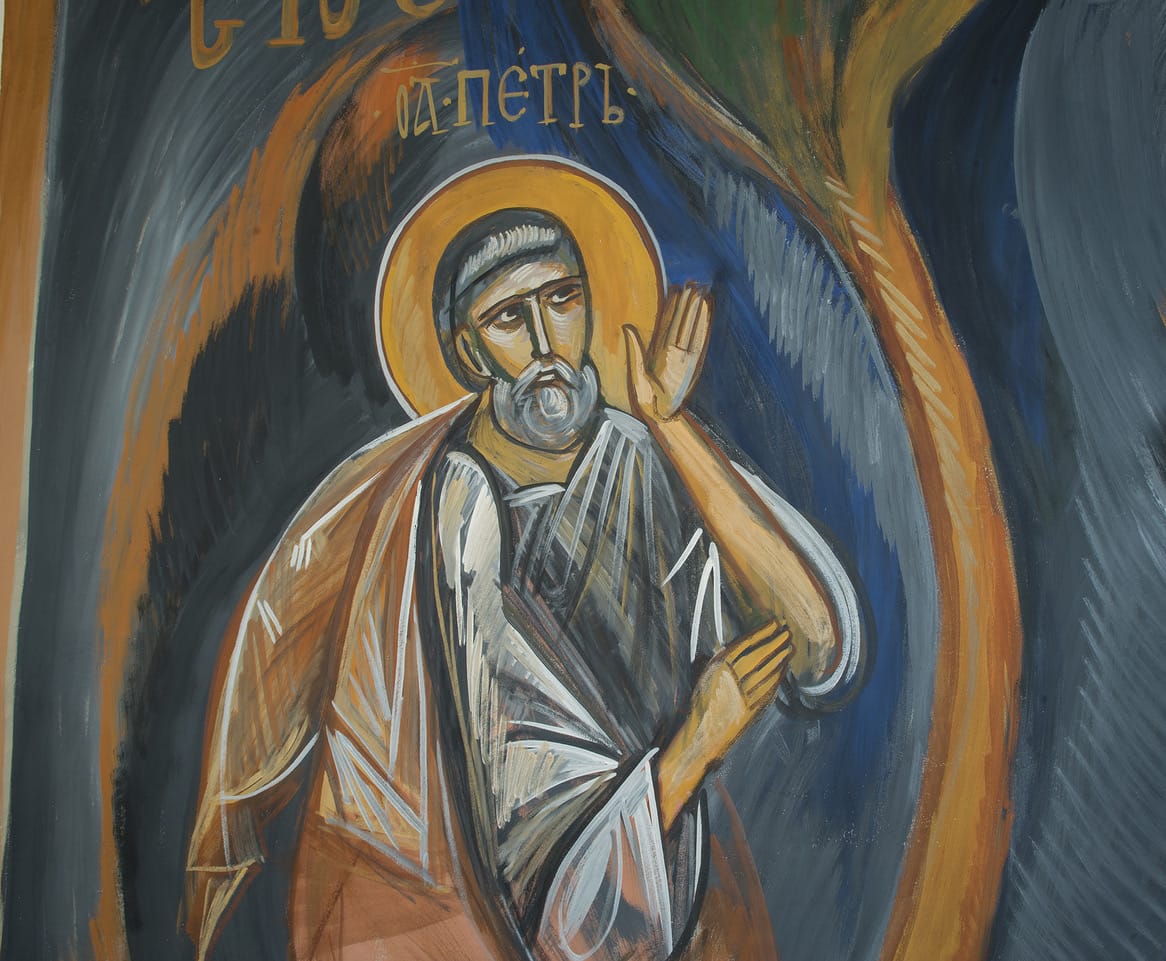

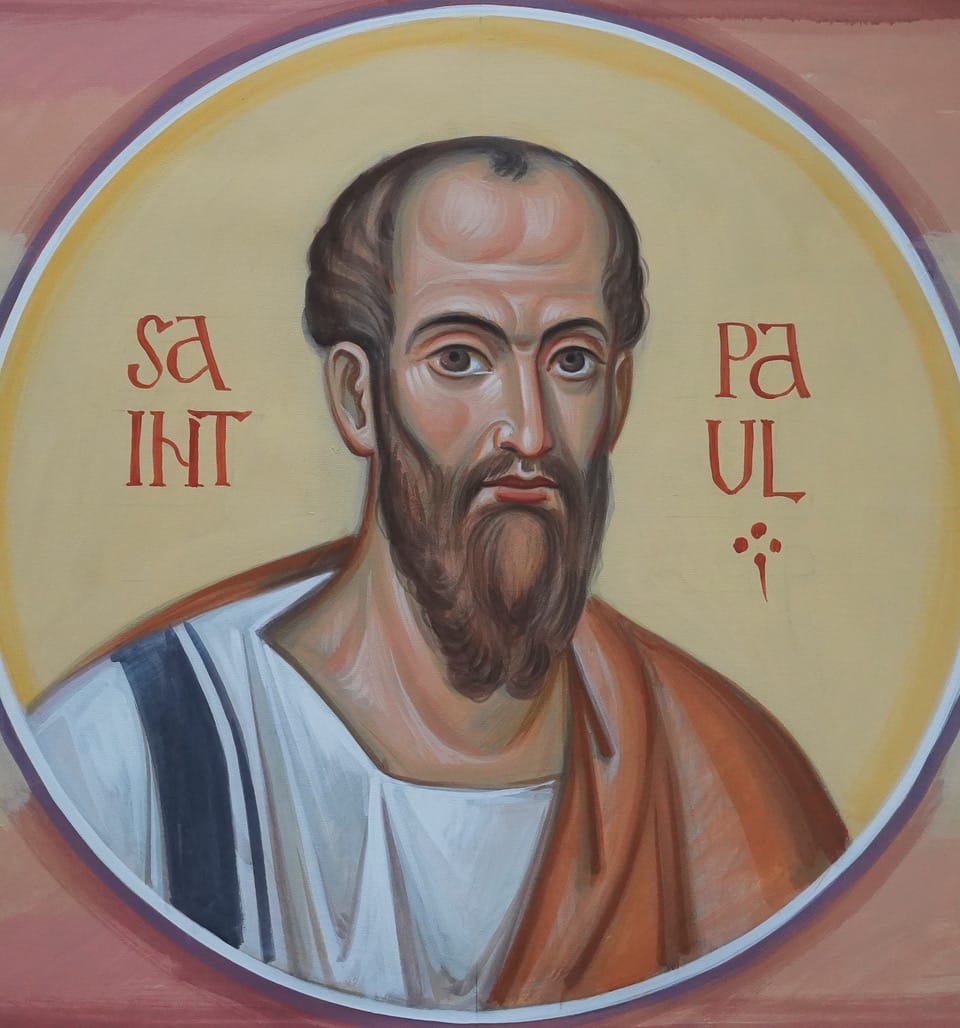

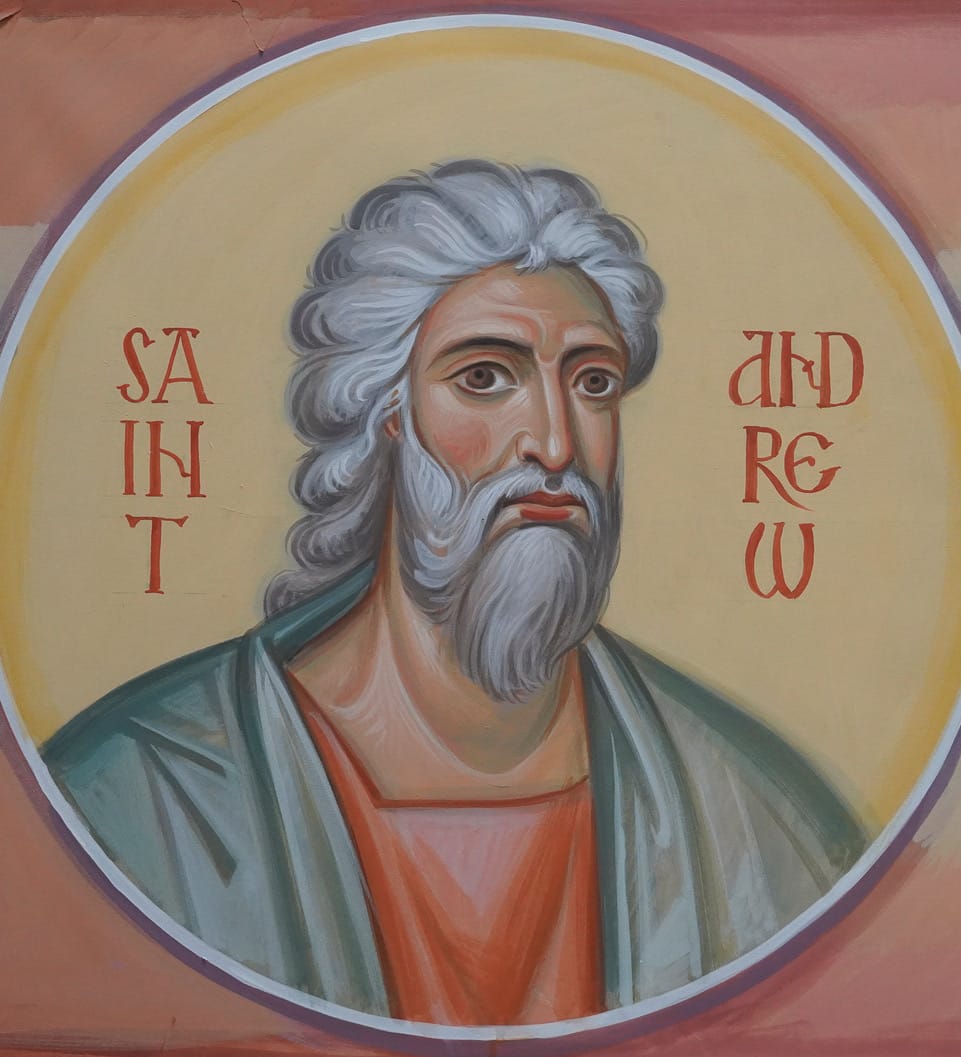

Thank you very much for the answer and for sharing your point! And I am really happy to see that the “questions” have generated some interest and your answers. Thank you also for sharing photographs of your works, illustrating how good relationships can be among the artists, parishes and clergy in the USA. I am very glad that your works were never damaged or destroyed.

You are totally right; Dn. Alexey’s works indeed were ordered “from above” with no consent with the parish. But I think it’s just a minor exception, because it’s the way Russian Orthodoxy is organized at the moment. The majority of church art is commissioned by priests who mainly think about pleasing their bishops rather than their parishioners, as our current church leader did so much to make priests become highly dependent on the bishops.

I am also deeply thankful to Andrew Gould for considering the works/photographs of Dn. Alexey seriously and seeing what I also think is the core of the phenomena!

Driving for 30 minutes through the district where the church is situated, I always felt like going through the unreal world of plastic. And only after entering the church, (which was also a replica), and seeing these murals, I had a sensation of something real and true.

So, the source of the problem with Dn. Alexey’s work is a continuous and increasing centralization of our church… Part of which was supposed to be our conference. But glory to God that it was not 🙂

The icon on St Nicholas Church seems highly appropriate for the location – it grabs the viewer in a stark surround.

There is a question that remains in my mind however- Is the “Made Without Hands” impression, a visual key, or trigger, in the recognition of an image as an object of worship, versus the sense of a painting of religious nature? (No longer a window)-

Dear Claire, thank you for the comment! I’m not sure I understood your question fully – would you please elaborate?

Dear Vladimir and all,

Speaking personally- The image on St Nicholas Church shouts out as almost a billboard to my mind, effective in that location rightly enough, though I would have trouble using it as a window to God.

Drawing the heart to our God is the purpose of the icon. Some people read imagery better than words. Bringing the soul in touch with the reality of God’s Love for us is the point of the iconographer. The icon needs a broader reference than suiting only the priest and the parishioners. A church needs to be a center for the world, our poor, fallen world. So many people have become blind to the Living Christ and His Love for us. The stumbling block is ourselves, still, the image that speaks to the heart in honesty, rather than our sophistication has the capability, by God’s Grace, of speaking volumes.

The ‘Made Without Hands’ reference (my question) – Does the human element, strokes of paint (versus blended paint), clearly coming from the human hand and mind, mar one’s ability to see God in the work?

I was just in the dentist’s office, sitting in front of a reproduction of a Van Gogh painting —a still life of iris, and, of course, a painting of many brush strokes—and seeing the artist’s reflected wonder at the beauty in that small piece of Creation.

The human heart has the ability to convey its love and awe for something bigger than itself and to bring others to its perspective, a powerful thought.

“Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as a sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.” 1 Cor 13:1 (seeming appropriate and happily sitting right before me!)

Dear Claire, thank you for clarification and interesting comments.

I don’t particularly like popular definition of icon as “Window to Heaven” mostly because it fails to give us any positive idea about how icon should look like.

I think that drawing the heart to God is not exclusive purpose of an icon. Many other things can draw a human heart to God: any true Art can (and should!) do that, but also Nature, human relationships, and many other things and ideas.

I also believe that an icon belongs to Church (not only to the priest and parishioners) but is open and available to everyone, and I completely agree with you that the stumbling block is only in ourselves.

As for the image in question: I think it would be better if Dn. Alexey would comment on that himself.

Without criticizing him, in my opinion, this is not the most successful image in this set. I haven’t seen it in person, so my guess is as good as anybody’s.

I would not differentiate between “rough” (with brushstrokes) and “smooth” (blended) manners of painting: both are just tools (or “styles” if you wish), which an iconographer uses to achieve the desired results. The iconographer can create good (and bad) icon using both manners.

The fact that this particular image does not appeal to you, simply proves the point that all people are different, and for someone this very image can speak volumes.

Dear Vladimir and all,

Thank you! This is well said and helpful to me.

And specifically to you, Dn. Alexey, I am not judging your work; I am only expressing my personal opinion regarding the exterior piece, which means nothing to the world at large, nor should it. But I want to say here, that the interior pieces fit St Nicholas Church beautifully, and I feel it is mind-expanding to see the kind of work you have done in a church setting.

So, still, the icon is hard to describe, a mystery that points to God.

Does anyone know what medium Dn Alexei uses to paint his murals? I agree with Andrew and the others, that his mural work is very appropriate for the setting, and that it is beautiful work. I am sorry to hear it was destroyed.