Similar Posts

A. Gould: How did you first set out to be an iconographer? What led to this decision, and what was your initial artistic training?

V. Grygorenko: I began painting icons long before my conversion to Christianity, which happened back in 1991. For nine years I studied traditional oil painting in the art studio at Dnipropetrovsk State University in Ukraine, along with my studies in mechanical engineering.

Even though I had a well-respected career in engineering prepared for me, I was thinking about becoming a professional artist. Before quitting my full-time job, I had to answer two important questions for myself, “What is beauty?” and “Why is art worth practicing?

Trying to answer these questions, I came across icons, which, being an atheist young man in an atheist country, I understood only as art objects. Initially, I researched iconography only as part of my studies of various spatial approaches in art, but eventually I came to the understanding that God is beauty, and the ultimate reason for the existence of art.

I was baptized in the Orthodox Church in 1991, amidst turmoil created by the collapsing Communist empire, and began my Christian life as an iconographer. There were absolutely no iconographers at that time to teach me, so I had to study on my own, learning traditional methods from rare books and from a few restorers in state museums. After a few years of self-study, I met Archimandrite Zenon in his remote skete near Pskov, and he taught me most of what I know.

A. Gould: How did you end up in Dallas?

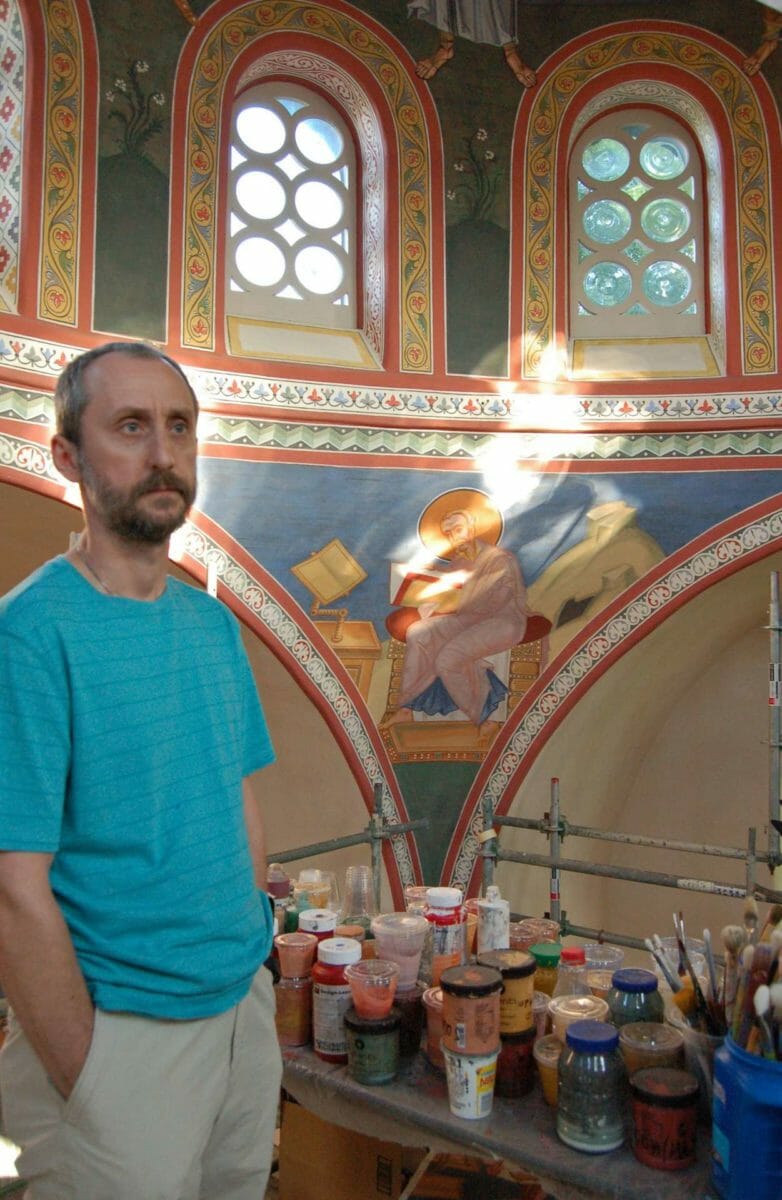

V. Grygorenko: Late Archbishop +Dmitri of Dallas, of blessed memory, invited me to Dallas twenty years ago to work in the newly built St. Seraphim Cathedral. After finishing murals in that church and a few others, my family and I decided to stay in Dallas.

A. Gould: Your style has evolved over time, apparently tending towards the archaic, and even Imperial Roman. Tell us about this, and to what extent you were influenced by Fr. Zenon and other contemporary iconographers in this trend.

V. Grygorenko: I am glad you noticed – it is true that my taste in iconography evolved over time, and I think this is normal. I believe that iconography is an art, and that development of a style is required for every artist. I would compare an iconographic style with a language – as you grow, you learn new words, see new sides of the same subject, and you become more confident in your use of these words.

While Archimandrite Zenon started with painting icons in a fifteenth-century Russian style, he later moved towards a classical style of twelfth-century Byzantine, and now develops his own style based on early-Christian art.

It is obvious that Christian art changed with time – but that development is not progressive: one style is not “better” than another, and a new style does not denounce a previous one.

Some researchers, like O. S. Popova, see the history of development of style in the Christian art as an alternation of two major tendencies in understanding of an image: Classical and Ascetic, or Dynamic and Static. Both of these tendencies appear in the very beginning of Byzantine art, in 6th -7th Centuries, and could exist simultaneously since then. (1)

Prevalence of one or another approach depends on dominating ideas which were important for the Christian thoughts of a given time and place. Contemporary iconographers must also pay attention to such ideas and strive to develop a proper language which would be able to express them. This is not about “changing dogma to suite our time”. On the contrary, we have to find the proper language in order to deliver the Christian message unchanged, but understandable.

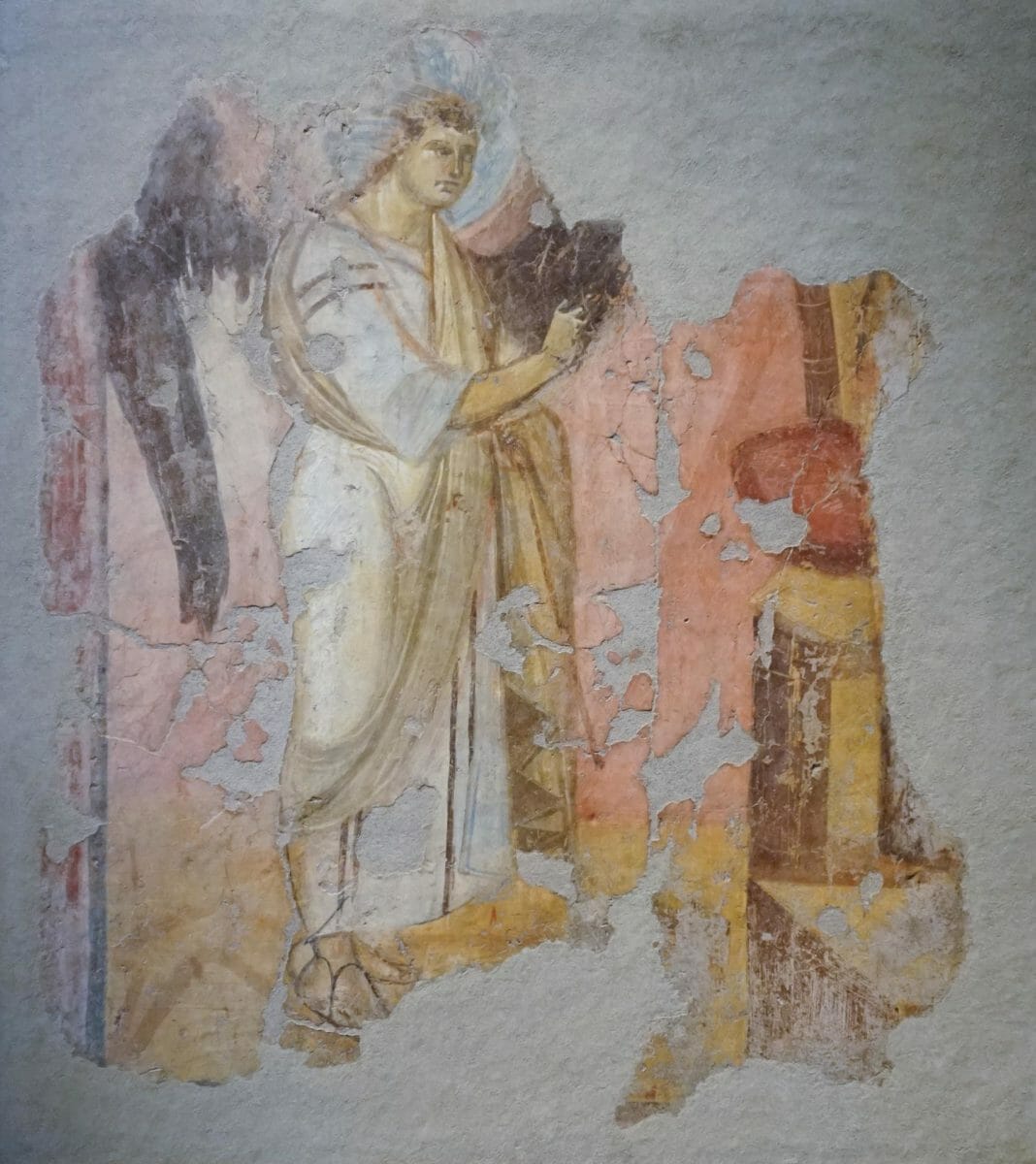

It is in search of this language that I decided to turn to pre-iconoclastic, even paleo-Christian iconography. I personally favor this term to “archaic”, since it shouldn’t be confused with words like old or outdated. The period between the fourth and seventh centuries was a time when Christian iconography developed from the art of classical antiquity, and, in its best examples, had a unique balance between spirituality and classical beauty of its form. We see this in the famous sixth-century icon of Christ from St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai.

Obviously, the work by Fr. Zenon in Feodorovskiy Cathedral in St. Petersburg has influenced me, but most importantly, it was my recent visit to Rome where I finally made it to the Catacombs and spent literally two days in the newly restored church of Santa Maria Antiqua.

What I saw there – the unusual compositions, amazing artistic quality of drawing, light, and elegant colors, was astonishing. Any honest contemporary artist must be jealous to see this 1400-year-old painting, which looks more contemporary than most canvases in our studios.

A. Gould: Photios Kontoglou, generations ago, went through a similar arc, towards more archaic painting, and eventually painting like an ancient Roman. Do you think there is something inevitable about this trajectory?

V. Grygorenko: I have seen quite a few examples of leading contemporary iconographers moving in this direction, so we, perhaps, can consider this a tendency. I think that this is a sign that the process of restoring broken iconographic tradition is generally completed. More and more iconographers all around the world are trying to develop the new iconographic style, bringing forward historic examples other than from the well-known period of the 14-15th centuries.

A. Gould: There is something about icons painted in this archaic style that I quite like. The big eyes, strong contrast, and bold brushwork are arresting to my attention. I find it much easier to focus on them. As a busy distracted person, I do not always have the patience to focus on a delicately painted and subtle icon. Do you think the movement to paint more archaic icons is a deliberate response to this phenomenon – that distracted modern people need more visually assertive icons? Or perhaps, because of our secular mindset, we benefit from icons in which the figure looks more like a real solid body, not so abstracted and ephemeral?

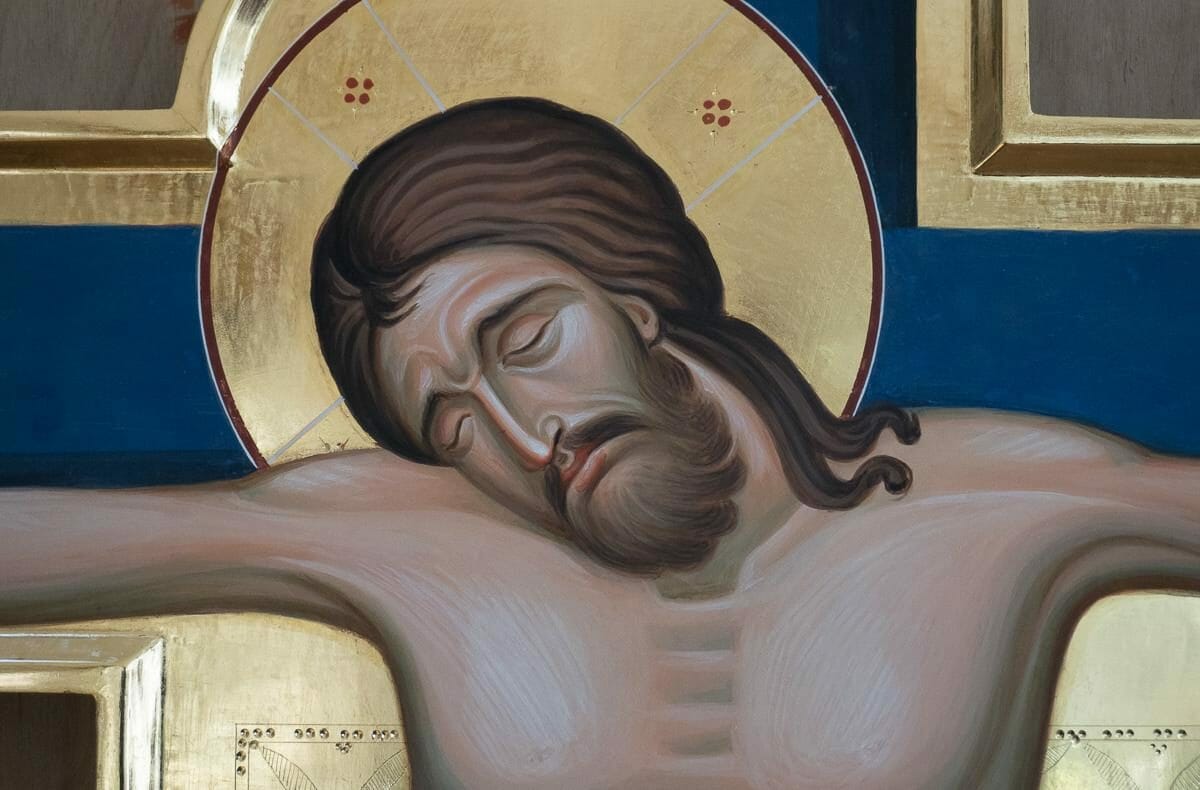

V. Grygorenko: I am not sure. I believe that icons, as well as people, should be different. Some people need delicate and subtle icons, some are more attracted to the “bold and assertive”. Since I personally prefer mural work, which, by the nature of this art, requires bold and assertive brushwork, many of my icons might display signs of this approach. There is also another consideration: iconography always should bear witness to Christ’s incarnation. God chose to become a man, not a bodiless angel, so anytime we depict a “solid body” we proclaim this very fact. The body should obviously be depicted transfigured, but not to the point that it becomes ephemeral and abstracted.

During the last century there was a popular idea that a human body in icons should look “spiritual” and “without any carnal beauty”. This school of thoughts was based upon old writings of Fr. Florenskiy and Leonid Uspenskiy. Their approach, which stresses opposition between secular and religious arts, now attracts reasonable criticism, and is considered outdated by many leading iconographers and researchers.

A. Gould: I particularly want to highlight your most recent work – the exo-narthex at St. Seraphim Cathedral. Please tell us about this interesting project.

V. Grygorenko: I have designed the exo-narthex as a sort of walk-way, which connects Archbishop Dmitri’s memorial Chapel and the main church building. It also serves as the main entrance to the Cathedral. Several relatively small rooms with only two windows and large doors serve as a transition between the rather busy street outside and quietude of the Cathedral nave. The exo-narthex was built together with the Chapel in 2015, but was left unfinished without murals for several years.

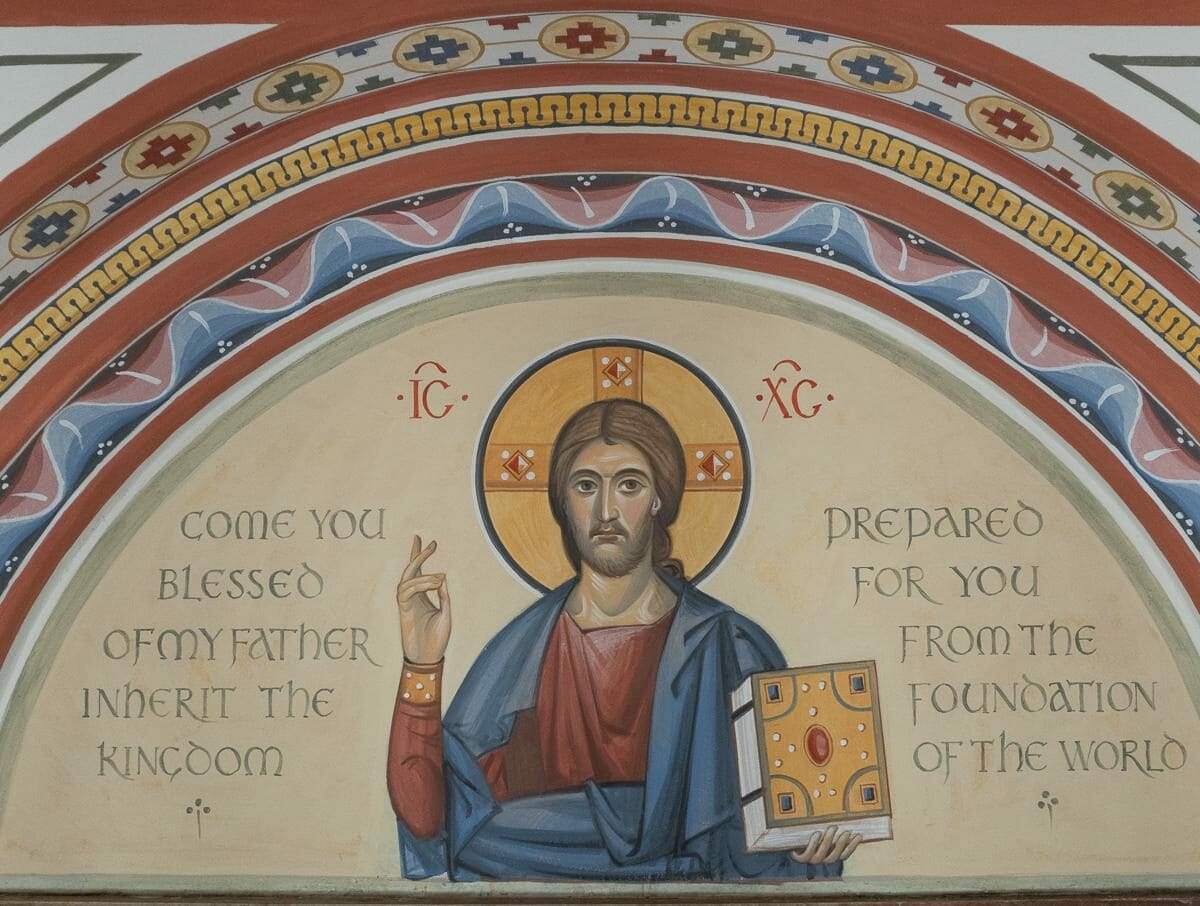

Our Cathedral is located in the center of a large city, so we always have visitors who come to see the church, and most of them are members of various Protestant Churches. Having these visitors in mind, I had to design mural decorations which would not overwhelm them from the very beginning with the intense colors and complex images which they would see in the nave, but rather I tried to use a language more familiar to them.

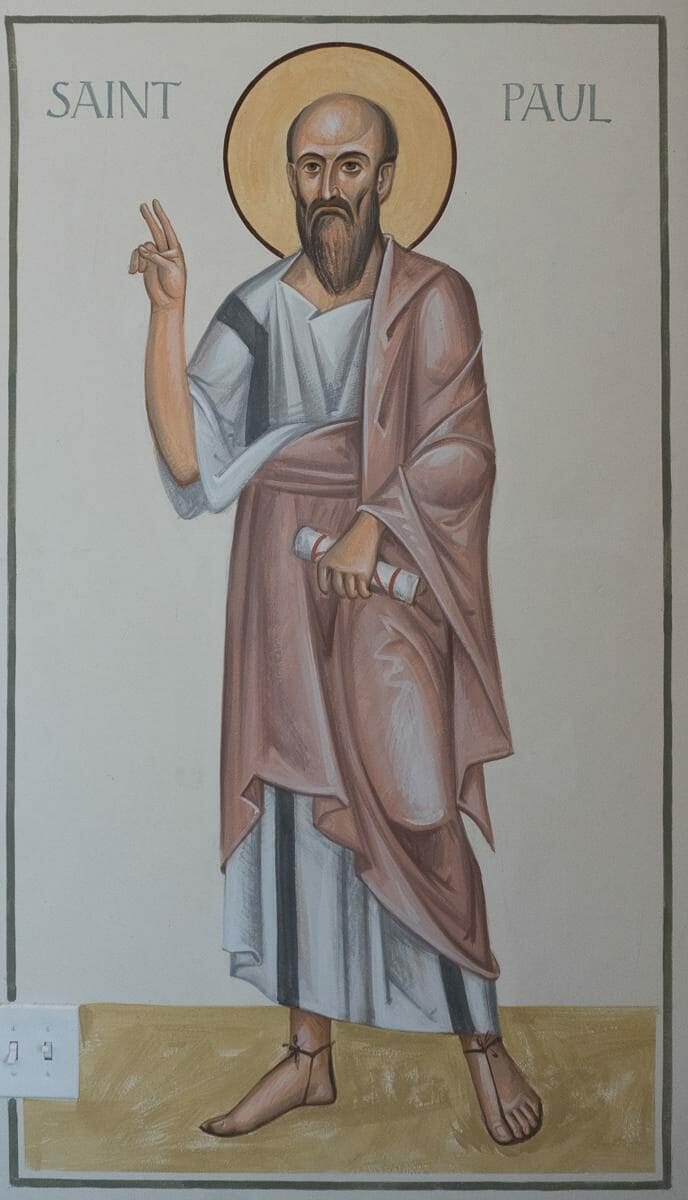

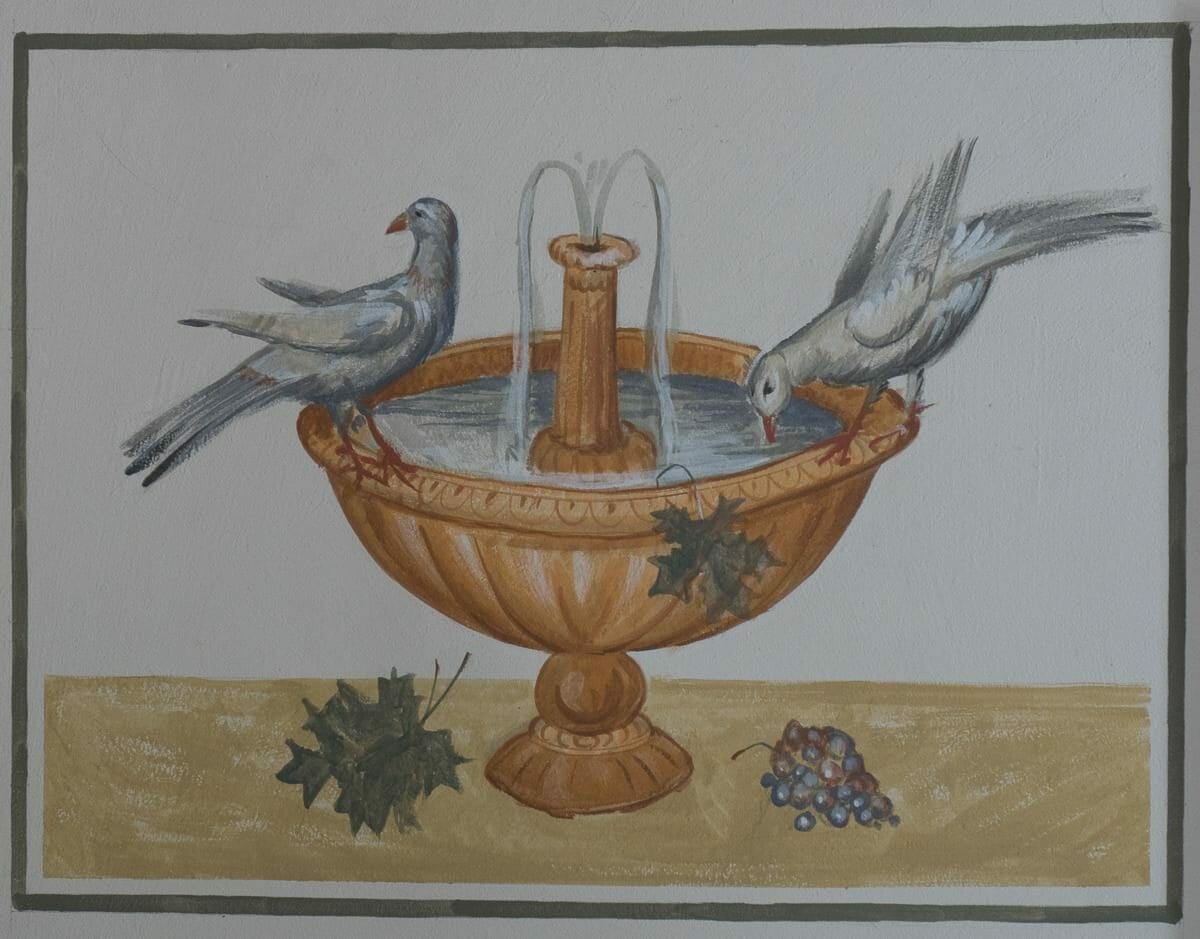

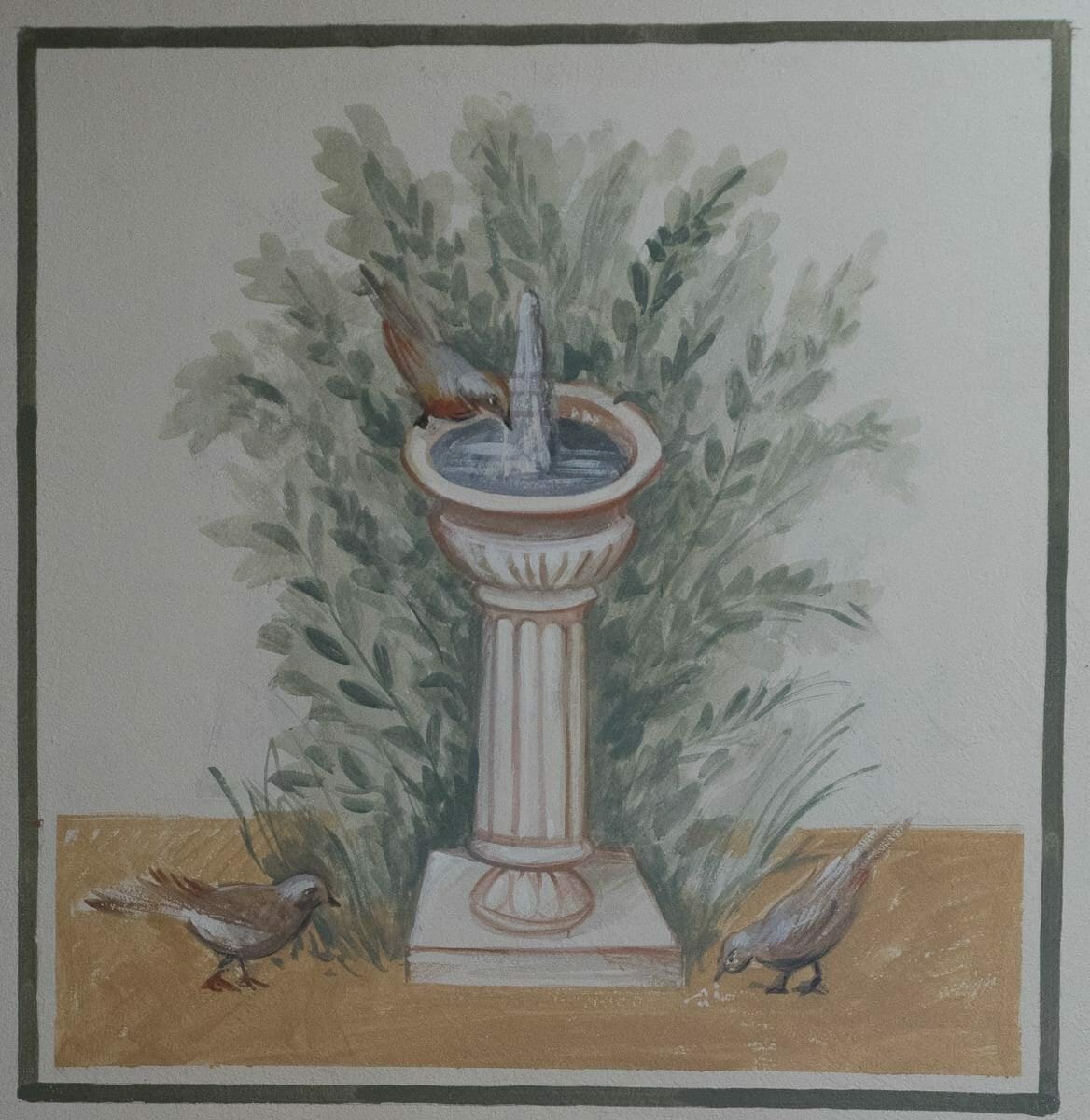

The paleo-Christian style of the Roman catacombs was my prototype. Using a pale, off-white background of exposed lime plaster, and simple red and green border lines, I was trying to recreate the sober and fresh atmosphere of the first days of Christianity. Having in mind our church’s location in the “Bible Belt”, a number of scripture quotes were incorporated into the murals. Getting positive feedback from many of our catechumens and visitors, I find that this was a good idea.

The main entrance to the Narthex has a large Venetian glass mosaic of Saint Seraphim, which greets every visitor with arms raised in prayer.

The entrance to the Cathedral is decorated with an image of Christ in a lunette over the doors, with His message to a visitor: “Come, you blessed of My Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world” (Matt. 25:34)

Those who enter from the Chapel are greeted with the message from Matthew 11:27-28: “No one knows the Father except the Son and the one to whom the Son wills to reveal Him. Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.”

The only full size standing figures in the narthex are of the Apostles Peter and Paul, which flank the exit door with an inscription addressed mostly to Christians who leave the church after liturgy: “Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”. (Matt. 28:19)

Four Angels, depicted on the arches, bring the cross and laurel crown to the medallion on the ceiling, symbolizing Christ’s death and glorious resurrection. There are also a few symbolic images from the vocabulary of early-Christian art: birds drinking from the fountain and from the chalice, which are symbols of life everlasting.

As a whole, these murals made in KEIM Silicate paint over lime plaster, blend rather nicely with the images in the Resurrection Chapel, with its light-colored pink background.

A. Gould: Many of your recent mural projects have light-colored backgrounds, which is uncommon historically. Tell us why you like to use this background color.

V. Grygorenko: Actually, light-colored backgrounds in church decoration was not as uncommon as we might think. First of all, gold backgrounds of mosaic decoration should be considered light, don’t you think? Secondly, these intense, dark-blue backgrounds of many contemporary church murals were totally impossible to imagine in ancient churches. Almost always, blue backgrounds were made in two stages. First, a medium-dark grey color, called ‘reft’ was applied on the whole background area. Then it was covered with a thin and transparent blue pigment, which, in fresco technique, makes the resulting color substantially lighter. With time, and after a bad restoration, blue pigment can be lost, so only dark grey with traces of blue can be seen. I believe this appearance inspired many iconographers (who were trying to restore lost iconographic traditions during the last century) to use such dark colors for the background.

In any case, pale colored backgrounds were much more common in pre-iconoclastic times – the murals of Santa Maria Antiqua being one of the best examples.

A. Gould: You work in silicate paint on dry plaster. What are the advantages of this medium, and how does it relate to your choice of style?

V. Grygorenko: Besides obvious technological advantages, such as extreme durability and water permeability, this paint has one significant advantage I like the most: it is as close to the appearance of ancient frescos as you can get, but at the same time, unlike a fresco method, it can be used on almost every surface in use in contemporary buildings. There is also one detail, which I consider a benefit, but others can call disadvantage: using this paint you have to work directly on the wall. Due to its nature, it is impossible to use this paint on a canvas in the studio and glue a finished mural in the church as wallpaper.

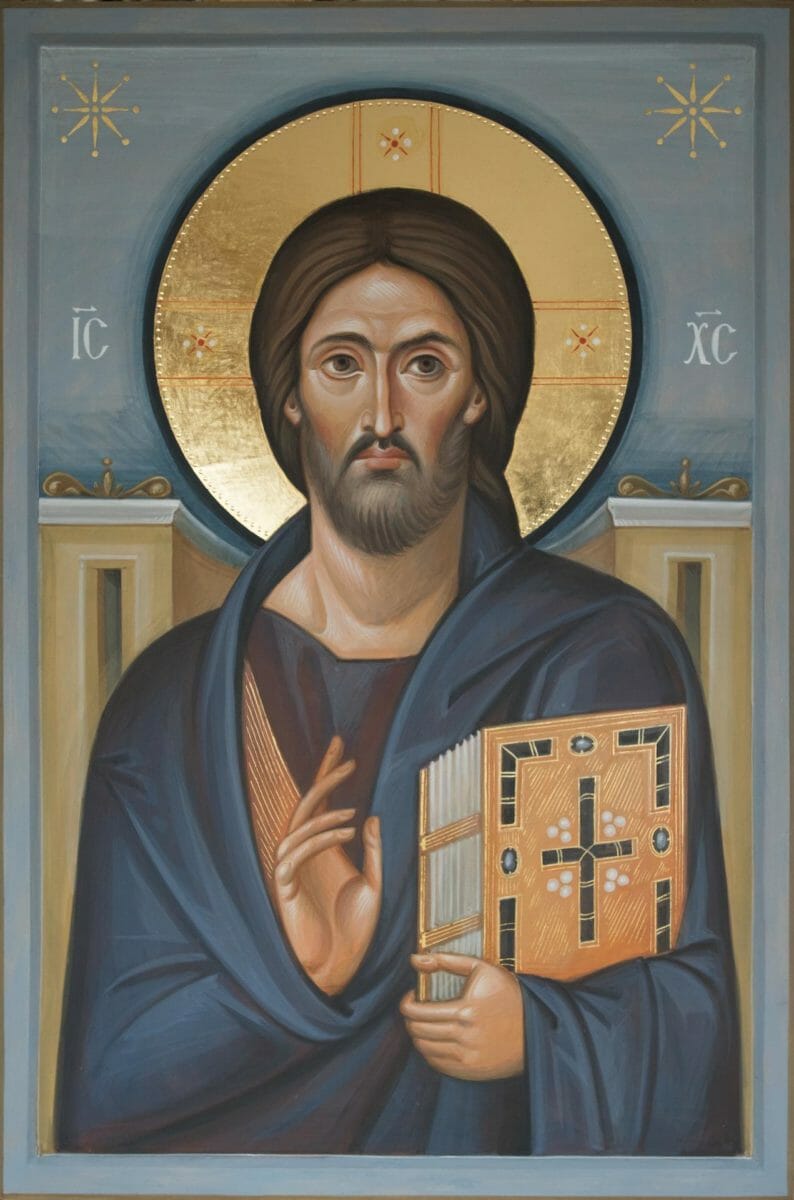

A. Gould: On your panel icons, your colors are brilliant and jewel-like, with such bright gold. How do you achieve this?

V. Grygorenko: For me, it is easiest to achieve that using authentic methods: egg tempera with mineral pigments and polished double-layer water-based gilding. It obviously takes more time and effort to create an icon using these methods, but, as you can see, the result is definitely worth it.

A. Gould: Americans are not used to such intense icons, but I think it would be a great benefit to American Orthodox to see more icons like these. In their rich materiality, they reinforce the idea that the icon is a unique sacred object, not a mere image that can be photographically replicated. This appreciation of the sacred object is much lacking in America. How do you find that people react to your icons?

V. Grygorenko: Frankly speaking, I find the situation with church art in America quite discouraging at this time. I personally never heard anyone complaining about my (or someone else’s) icons, but I see that, excluding a few rare exceptions, Orthodox church communities do not always appreciate iconography.

Quite often, our parishes consider icons or murals as sort of a necessary burden which needs to be done to satisfy some ancient tradition to have images in the church. It does not matter how these images will look like, as long as they are cheap and present.

Unfortunately, that is not specifically an American problem – such a mindset is common in many orthodox countries around the world. Ukraine, Russia, Romania – they all have their specifics, but being a member of the OCA, problems of American orthodoxy are closer to me.

There are dozens of well-established parishes everywhere across the American South which are covered from top to bottom with cheap reproductions of icons. I am not talking about newly organized missions with fifteen members. On the contrary, these are old, well established parishes of 120+. Six-foot-tall vinyl reproductions of small originals, placed right next to little prints of large murals without any order or system create a bizarre experience. But, “our church is traditionally decorated with murals, and we did not spend too much money!”

In cases like that, the problem is not in the lack of money, but rather in a special mindset, as you call it correctly: lack of appreciation of the sacred object.

For example, just a year ago, one large, old parish in the US (thank God, not part of the OCA!) spent a year and hundreds of thousands of dollars to cover almost 10,000 square feet with vinyl prints of murals. Besides the obvious fact that all these pictures will start to fade away in a few years, the dissonance between various parts of images enlarged from little sketches and blended in Photoshop is overwhelming.

That is obviously an extreme case, and most often one can hear something like, “we are going to use these printed icons or wallpaper murals for limited a time only, until we will build a REAL church”!

That argument is common and needs to be addressed.

First of all, from my experience, a parish which chooses to go into this direction will not be able to build anything in dozens of years, and all of these years they will pray in front of faded prints. The printed murals will most likely never be replaced. Metaphorically speaking, nobody in their right mind would advocate for replacing a church choir with sound recordings of professional singers, based on an assumption that “we don’t have time and resources to train our people to properly sing complex music for Orthodox Liturgy. We will stop using these recordings someday, when God will bless us with an experienced music director and a few trained good voices”. How fast, do you think, this parish would grow?

Secondly, real icons are not prohibitively expensive, even for a small parish – they will never be as cheap as an icon print, but it is not required to have twenty of them at once. A relatively inexpensive, but pretty iconostasis, with a few hand-painted icons and without too much wood carving and gold, can be designed by a professional architect or iconographer.

I am not trying to say that making an icon print is some sort of sacrilege. On the contrary, a small print of an icon can be used for private devotion. But nothing can replace the authentic experience of prayer with a hand painted icon, even if it is not of the best artistic quality. Easy access to icon reproductions encourage overcrowded icon corners with dozens and dozens of little icons and cards, which only scatter our attention, rather than concentrate it in prayer.

In our Post-Modern times, when surrogates occupy all areas of our life, people struggle for authenticity. This is what I hear from many of our catechumens: “We decided to join the Orthodox Church because we were not satisfied with the lukewarm, surrogate spirituality of our former church.”

To these people we simply cannot offer “high quality printed murals” as the sacred objects which are an essential part of Orthodox theology. Doing that would be refusing to fulfill our missionary role as a Church.

A. Gould: Thank you, Vladimir, for sharing your thoughts with us, and for your beautiful work, as always.

Vladimir Grygorenko’s website can be found here.

Previous articles on the OAJ about Vladimir’s work can be found here and here.

(1) See for example, Popova, O. S. “Path of Byzantine Art”, Moscow, Gamma-Press, 2013 (in Russian)

Andrew, thank you for another wonderful interview!

I love this man’s work and am really happy he has chosen to make Texas his home. I think the white backgrounds are interesting when they are used in white painted churches and also in hot climates like Dallas. It seems to work well as as a memorial chapel to be intended to appear like a Roman catacomb. I think it works as an experiment – and we should do experimental things these days that don’t conflict with our faith and traditions. This doesn’t conflict with anything. I am not sure the silica paints look like fresco to me. Are they absorbed into the surface or just dry on top? Of course I have never seen Vladimir’s work up close. I hope he will return to traditional colors for his backgrounds. His Neo-Byzantine works are exceptional and he has developed his own unique and distinct interpretation of the style. I think is is very hard – even lonely – for iconographers in the USA to work without the support and input of fellow artists. It must be hard for Vladimir to convince OCA churches to commission good work at reasonable prices when they have nothing to compare it with. In Russia, Belarus and Ukraine there as so many projects to use as reference points for styles, artistic quality and cost.

Thank you, Bob, for the comment.

The surface of fresco painting can look quite different depending on the time, style and technology used.

KEIM Silicate paint, when applied on thin lime plaster, creates a mineral matte appearance without distracting reflections, which is much closer to the look of fresco on the wet plaster than it is possible with Acrylic paint.

Unlike Acrylic, Silicate penetrates to substrate and does not create a film on top of it, so there is nothing to peel off.

You can find more information and some close-ups on my website http://www.orthodox-icon.com

I have heard from one of that group, that Old Ritualist temples often have only a few icons, as they will not use reproductions.

Thank you Vladimir for your balanced input on the issue of reproductions.

One of the aspects of your work I’ve always appreciated is it’s clear logic and directness. I suppose that’s one of the reasons why you enjoy working on murals, since it calls for a broad, more painterly approach to the handling of form, line and color application.

Do you have the time to teach pupils in this stage of your professional career? I think making your knowledge accesible to serious seekers will help bring some balance to the state of icon painting in the US.

Fr. Silouan, Thank you for the kind words about my work. I think that the main problem with the icon painting in the US today is the lack of interest in iconography amongst the general population of Orthodox faithful.

In order to solve this problem, a joint effort of the Church as whole is required, which includes, first of all, the work of our Seminaries, theologians, priests and then, iconographers.

It is relatively easy to teach the technological aspects of icon painting, but you cannot make one an iconographer in a “six days icon class”.

At this time, I believe, professional seminars, discussions and collaboration on actual projects would have bigger impact on the development of the iconographic community in our country.

But then, again, from my experience, most parishes don’t see any difference between good or bad iconography, since the main criteria still are price and expedience.

In any case, if you wish to discuss this more, we can do it through email.