Similar Posts

Editorial Preface:

This article was written by Dr. Peter Brooke, an Orthodox Christian painter and writer living in Brecon, Wales. He is the author of “Albert Gleizes: For and Against the Twentieth Century,” a major biography of one of the most important pioneers of Cubism. Dr. Brooke studied painting in France with the distinguished potter Geneviève Dalban, one of A. Gleizes’ successors. Thus his thoughts on the “practice of painting” in the following article reflects his engagement with the pictorial principles expounded by A. Gleizes.

I’ll parenthetically say just a few words about him. First of all, as a father of Cubism he cannot be easily categorized and dismissed as just another “modernist.” Yes, he’s inextricably part of modern art’s history, yet I have found that the overall ethos of his life and thought places him in a category of his own. You might not agree with all of his ideas, or even like his paintings, but he’s a man whose integrity commands respect and thoughtful study. For one thing, he pursued objective pictorial principles which he saw as correlated to the nature of Man, rather than the mere arbitrary whims of subjectivism. His understanding of the tripartite nature of man is quite Orthodox. Among the theorists of modern art, he’s the only one I have encountered who upholds the primacy of the “noetic faculty,” calling it the “Intelligence.” He soon grew disillusioned with the cult of the machine, the excesses of mass production, and all the various abuses of industrialization hailed as “progress.” He was no nihilist, or atheist, but rather believed in God and oriented his work accordingly. He deplored scholasticism, nominalism, humanism and the static sensuousness of Renaissance painting. But his heart rejoiced in the spiritual rhythm of the works of the Middle Ages prior to the 12th century. He expounded a philosophy of craftsmanship based on the medieval model of the workshop, in which the apprentice was taught slowly and initiated by the master. He encouraged his fellow artists and intellectual peers to return to the soil, engage in manual labor and agriculture, live communally and contribute to the cultural enrichment of village life in their practice of a traditional craft. Moreover, acutely aware of the spiritual dearth of his time, he aimed to make of his work a kind of sacred art based on the Christian “state of mind” from which the “rhythmic” Romanesque masterpieces arose. Hence, paradoxically, although he was very modern in his commitment to Cubism he also, in spite of his flaws and the limitations of his predicament, seriously sought after the principles of Tradition.

So, in other words, he’s a clear example of a ‘threshold’ artist in which can be found concerns that parallel those of ours as liturgical artists. Finally, in A. Gleizes we encounter another way in which we unexpectedly find, as we have explored previously, some aspects of the icon and modern art in convergence.

But for all his yearning for the traditional Christian “state of mind” prior to the 12th century, there is another side to Gleizes that is unacceptable and hard to comprehend from an Orthodox perspective: his positive view of the Council of Frankfurt. As a non-representational painter, he had a bit of an “iconoclastic” streak.

In this article Dr. Brooke, finding this side of Gleizes’ views problematic, moves on to explore the cultural implications behind the tensions that arose between the Frankish Court and the Byzantine iconodules surrounding the veneration of icons. He sees the matter as more complex than just a question of power politics and a misunderstanding precipitated by mistranslations. Rather, in his view, it goes deeper, touching on the confrontation between two distinct cultural approaches to the image as such: one based on the principle of “rhythmic” ornamentation (Insular art) and the other having to do with “likeness”(Classical art). Herein we find an art of “contemplation” and “veneration” respectively. While, on the one hand, some might dismiss the first tendency as mere “decoration” or “meaningless” abstraction; the second runs the danger of becoming just a kind of “photographic” illusionism, or fixation on appearances. The reader might not always see eye to eye. Nevertheless, Dr. Brooke points at new angles that perhaps we have overlooked, but can serve to enrich our approach to iconography and evaluation of a very important historical moment.

The article was originally delivered as a talk and published in, “The Beauty of God’s Presence in the Fathers of the Church: The Proceedings of the Eighth International Patristic Conference, Maynooth, 2012” (Janet E. Rutherford ed., Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2014).

We would like to thank Dr. Peter Brooke and the Four Courts Press for allowing us to republish the article in OAJ.

* * *

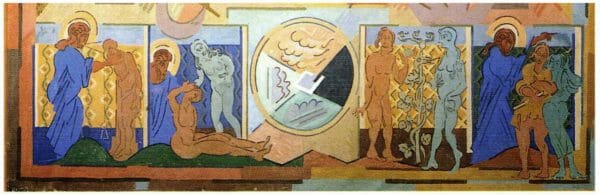

I want to begin with a brief account of this painting by the twentieth century French painter, Albert Gleizes.

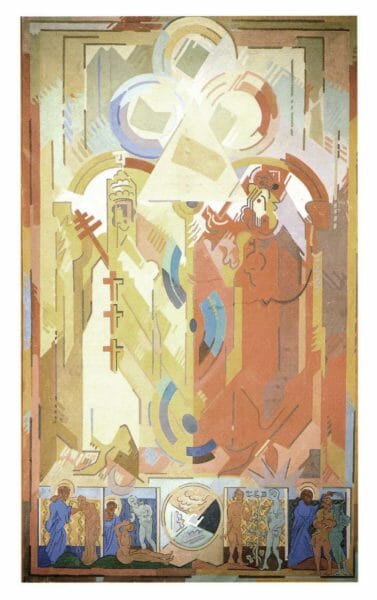

[Fig 1] Albert Gleizes: Autorité spirituelle et pouvoir temporel, oil on canvas, 336 x 203 cm, not signed or dated (1939-40), Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, cat rais no 1644. Ⓒ ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2013. (Photo from Albert Gleizes – Le cubisme et son dénouement dans la tradition, Exhibition catalogue, Lyon, Chapelle du Lycée Ampère, 1947

It is commonly known by the title The Pope and the Emperor but its real title is Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power – the title of two books written by writers who interested Gleizes, the Hindu theologian Ananda Coomaraswamy and the esoteric philosopher René Guénon.

The painting is divided into three parts which illustrate in an almost programmatic way the three levels of human nature which Gleizes believed had to be reflected in the practise of painting if it was to respond fully to our human need. I cannot do better than take up an account by Gleizes’s pupil and friend, Jean Chevalier: [1]

‘The three natures of reality: at the bottom, space (the figurative element as it is experienced by the senses) with Genesis.’

That is, the creation of Adam, the creation of Eve, the eating of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, the expulsion from Eden, all represented in what is for Gleizes a relatively figurative manner. Then:

‘Middle register: the Pope and the Emperor and their will (the ascending spiral). This is the level of witness – time, cadences, characteristics that were derived from the experience of Cubism.’

The figurative element, which is still present, is broken up into an interplay of straight lines and curves which put the eye into movement, ultimately a spiralling movement. Then:

‘at the highest level, the Trinity – the three colours of light.’

The ‘three colours of light’ being the primary colours (in pigment form, not in the spectrum itself) – red, yellow and blue which, combined, make up grey which has the property that it will take on the complementary of any colour placed next to it, thus recreating the full colour circle, the fulness of light. An interesting analogy for the Trinity but not one, so far as I know, that is found in the traditional literature.

In the context of this particular talk I do not want to go into great detail on the technicalities of a painting like this but I do want to stress these three, indispensable and inseparable, orders of reality:

(1) Space, which, considered in purely painterly terms, is a matter of proportion and measurement and of a ‘figure’, or ‘image’, representational or otherwise, which can be seized by the eye all at once –

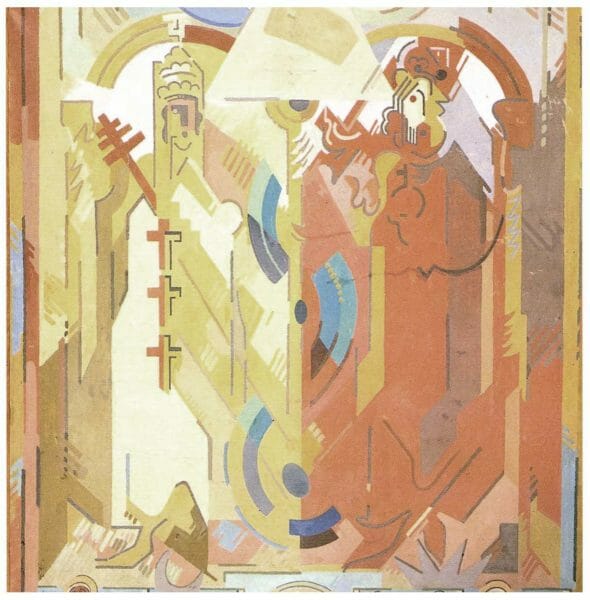

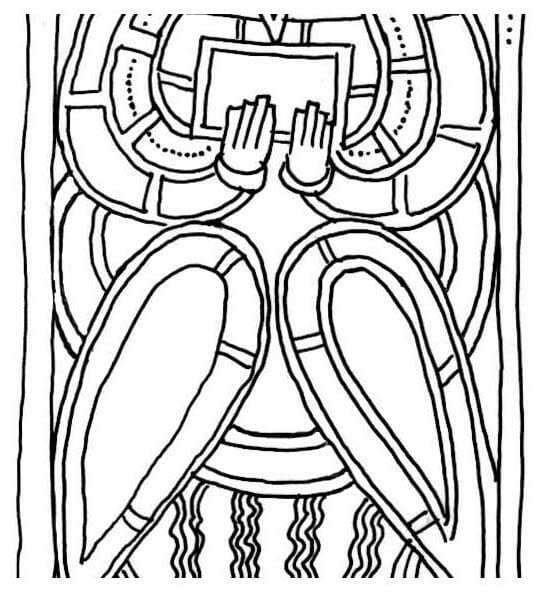

Fig 2b

(2) Time, which is present in the painting through the way in which the eye is put into movement from one thing to the other, most obviously here in the central blue spirals, and

(3) Eternity, which is present through the overall form of the painting which is at once single and circular and consequently experienced as both moving and unmoving.

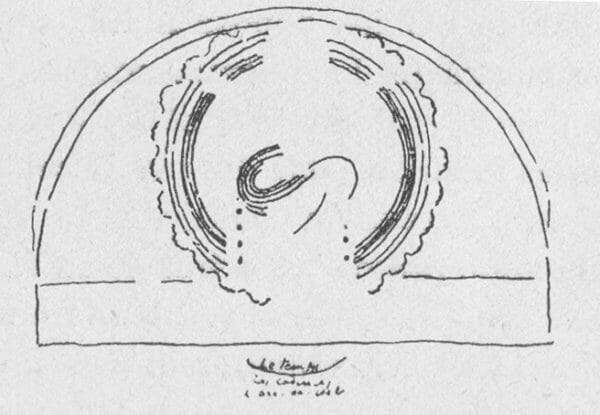

[Fig 2] Illustration from Gleizes: Homocentrisme (1937) based on a Christ in Glory from the Abbey Church of St Savin sur Gartempe, Poitou, France.

And I would like to point to the parallel there is – and Gleizes was very conscience of it – to the threefold anthropology that we commonly find in patristic literature: not the duality of body and soul but the triad of body, soul and spirit – aisthesis (corresponding to the senses), psyche (the emotions and mental processes) and nous – the ‘spirit’, ‘intellect’, or ‘noetic faculty’ being the means by which we can enter into theosis, union with God.

A POLITICAL DIFFERENCE

I have called this talk The Seventh Ecumenical Council, the Council of Frankfurt and the Practice of Painting and my own main interest lies with the practice of painting. I am myself a painter, a disciple – the term is not too strong – of Albert Gleizes. I could claim that most of my serious intellectual interests turn in concentric circles round him. There is an Irish dimension to this interest since his pupils, and again we could say ‘disciples’, include the Irish painters Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone. In addition to his painting, Gleizes also wrote, mainly with a view to trying to understand and explain what was or ought to be permanent in the changes introduced through Cubism, and this led him to develop a broader historical view, understanding changes in painting styles as reflecting changes in the spiritual disposition of the wider society. In a couple of places – in his large study La Forme et l’Histoire published in 1932 and in his lecture Art et Religion, given about the same time -he evokes the Council of Frankfurt and expresses approval for its rejection of the veneration of icons. [2] Since I am also an Orthodox Christian and I venerate icons this poses a problem for me and it is largely my desire to explore this problem that has led to this talk. I shall begin with a brief and necessarily superficial account of the eighth century controversy between, on the one side the Eastern Empire and the Papacy and, on the other, the court of Charlemagne which was soon to become the court of the Western Empire. My account owes a great deal to Thomas F.X. Noble’s book: Images, Iconoclasm and the Carolingians. [3]

The Seventh Ecumenical Council held in Nicaea in 787 AD (and therefore often referred to as Nicaea II) was the last generally recognised ecumenical council of the Roman Empire. It was also the last council held under the auspices of the Emperor at Constantinople at which all the great historical patriarchates of the original Roman Empire, including the Papacy, were represented. Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem sent representatives but they were already under Muslim rule and Rome was already engaged in the long process of detaching itself from the Eastern Empire in alliance with the Franks in the West.

The main business of the Council was to assert, or to re-assert, the validity of religious images and their veneration in reaction to the earlier Council of Hiereia, which also regarded itself as the ‘Seventh Ecumenical Council’ (though its findings had been vigourously opposed by Rome). The Council of Hiereia had been summoned in 754 by the Emperor Leo III whose policy of rejection of religious imagery was continued by his son, Constantine V. Nicaea II was summoned by Constantine V’s widow, the Empress Irene, acting as regent for her son Constantine VI. Its canons are still regarded as authoritative within both Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy but in the event an iconoclast programme was renewed soon in the following century by Leo V. It was only with a council held in the Blachernai Palace in Constantinople in 843 – again under the auspices of an Empress acting as regent for her son – that religious imagery and the veneration of religious images were accepted definitively as part of the practise of the Orthodox Church. It is this event that the Orthodox Church celebrates on the first Sunday of Lent as the ‘Triumph of Orthodoxy’.

The Council of Frankfurt was held in 794 under the auspices of Charlemagne, six years before he was crowned Emperor of the West. Canon 2 of the Council states:

‘The question of the recent synod of the Greeks, which was held in Constantinople for the adoration of images, was entered into the discussion. One finds written there that they who do not pay to the images of Saints the same service or adoration as to the divine Trinity are bound by anathema; our above-mentioned holy fathers, utterly rejecting such adoration and service, hate it and agree in condemning it.’ (Noble, p.170)

Of course the Seventh Ecumenical Council said no such thing. It seems that the very bad translation of the Acts of the Council in Nicaea which had been received by the Frankish court quoted the Greek Bishop Constantine of Constantia in Cyprus as saying: ‘I receive and embrace honourably the holy and most venerable images according to the service of adoration which I pay to the consubstantial and life-giving Trinity.’ In fact, in the original Greek text he had said that images should not be paid the service or adoration due to the Holy Trinity.

So if we were to confine ourselves to considering just the Council of Frankfurt we might say that the quarrel with the Council of Nicaea was based on a misunderstanding, and we might even say that all that was being condemned was a personal opinion expressed by one of the Bishops present at the Council, though the grammar of the Frankfurt canon suggests condemnation of the council as a whole. But in fact there is much more to it than that.

In 792, the court of Charlemagne sent the Pope – Hadrian I – a polemic against the Nicaean Council – the Capitulare adversus synodum. This can be seen as a first draft of a much more ambitious work, the Opus Caroli Regis contra Synodum which was in the course of preparation. The importance attached to the Opus Caroli can be seen in the very name – it was written as if written by Charles himself. There has been some dispute as to who actually did write it and for a long time it was ascribed to Alcuin of York, who may indeed have had a hand in it. But the consensus opinion is now that it was written by Theodulf who, some six years later, was to become Bishop of Orleans.

Before the Opus Caroli was finished, however, the Pope had sent Charlemagne a lengthy ‘Responsum’ to the Capitulare, defending the conclusions of the Seventh Ecumenical Council. Thomas Noble argues that the Responsum came as something of a blow to what was intended to be an ambitious assault on the theology of Constantinople. This is also the period in which the controversy over the Filioque was being prepared and part of Theodulf’s argument was based on the Filioque in the form given it by Augustine of Hippo in his treatise on the Trinity. (Noble, pp. 175 and 195)

The Opus Caroli has four volumes. The first two volumes are tightly structured, the third less so, the fourth volume reads like a draft. The implication is that the project was abandoned, probably as a result of the Pope’s intervention. Nonetheless, the Nicaean Council was condemned by the Council of Frankfurt, but in what Noble (p.158) calls ‘an odd and ambiguous way’. None of the propositions defended in the Responsum were condemned, though many had been vigorously attacked in the Capitulare and in the Opus Caroli. None of the actual canons of the Nicaean Council were condemned. What was condemned was an eccentric proposition which the Latin translation had attributed – wrongly as it happens – to one of the participants in the Council. But this proposition was condemned as if it was a proposition of the whole Council. The determination to condemn the Council remained intact but it needed to be done in such a way as to avoid open conflict with the Pope. The Pope, who was represented at Frankfurt (as he had been at Nicaea) must have been fully conscious of what was happening and to have made a decision to let it pass (he too had an interest in avoiding open conflict with the Franks).

Obviously what is happening here is very political. We have been describing part – a major part – of the process by which a new Frankish Empire came into existence in full moral and intellectual independence from the Roman Empire whose political centre was Constantinople. You may have noticed that I have so far avoided using the term ‘Byzantine’. I think the term ‘Byzantine’ is misleading, giving an impression of something exotic and oriental. Although the language of the Eastern Empire was Greek, its people called themselves ‘Roman’ – they saw themselves as the continuation of the Roman tradition politically and culturally. And this viewpoint would have been shared by old Rome, as represented by the papacy. It was only with reluctance that the papacy was turning to the Franks for protection. I shall indeed shortly be arguing that the art of the West was more exotic and foreign to our own presuppositions than the still classical art of Constantinople. [4]

There had of course already been many quarrels, political and theological, between old Rome and new Rome – quarrels in which, on the theological side, whether it was a matter of Arianism, Monotheletism, or the use and veneration of images, Rome was usually on the side that both the Catholic and Orthodox traditions would eventually recognise as ‘orthodox’. But there had been similar quarrels among all the historical patriarchates, quarrels that had already led to schism in the case of Alexandria. The papacy throughout the eighth century had consistently opposed the Imperial policy of refusing the use or veneration of religious images, notably in councils held in 731, under Gregory III, and 769, under Stephen III. Indeed, as Noble, points out (p. 123), the council of 731 was the first to impose an anathema on anyone who refused the veneration of holy images. The Nicaean Council did not go that far, merely authorising the veneration of images. Hadrian had written to Irene when she assumed the regency calling on her to restore the use of religious imagery. The Seventh Ecumenical Council could be seen as something of a triumph for the papacy. Hadrian’s letter to Irene was published as part of its Acts and the canons included what could be construed as an acknowledgment of papal supremacy. In these circumstances, the Frankish rejection of the Council must have been extremely unwelcome.

Put very crudely, then, the Franks were determined to break completely with the Eastern Empire. The moral authority they claimed lay not in their continuity from the political tradition of Rome but in their faithfulness to the Christian idea. As such they had an interest in believing that Constantinople was not faithful to the Christian idea. I wonder in parenthesis if the Arianism of the Visigoths and Ostrogoths might have performed a similar role, enabling them to assert a new, Christian authority in opposition to the old Authority of Rome, continuous as it was from pagan Rome. Defenders of the veneration of images, as we shall see, used an analogy between the respect given to a saint through respect for the image of the saint with respect for the Emperor shown through respect for the image of the Emperor. The Opus Caroli argued that this type of veneration given to images of the Emperor should have been eliminated with the coming of Christ and in this context it quotes the Seven Books against the Pagans by the fifth century Paulus Orosius, arguing that Roman power was a continuation of Babylon. To quote Noble: ‘When the passage drawn from Orosius about Rome’s being the heir to Babylon was read out in Charlemagne’s presence, a scribe recorded his reaction: “Wonderful!”‘ (Noble, p. 199) Orosius, it may be noted, was a friend of Augustine of Hippo, and a similar argument can be found in Augustine’s City of God, which was one of Charlemagne’s favourite books.

Clearly this desire for a clean break from Rome was complicated by the relations between the court of Charlemagne and the papacy. I don’t want to get too involved in that immensely fraught topic but what is important for our present purpose is the determination of the Carolingian court to create around itself an intellectual life independent of the papacy – with Alcuin and Theoldulf as key players in the project. Although the support of the papacy was obviously helpful to establishing adherence to orthodox Christianity as the source of the court’s authority, the Carolingians were far from endorsing anything resembling a doctrine of papal infallibility. Later, in the context of the revival of iconoclasm in Constantinople, a group of ecclesiastical counsellors were to advise Charlemagne’s son, Louis the Pious, that:

‘Furthermore, when your father of holy memory, had that same Synod [Nicaea II] read out in the presence of himself and his men and had criticised it in many places, as was fitting, and when he had particularly noted some passages that were especially open to severe censure, he sent them to Pope Hadrian through Abbot Angilbert, so that they could be corrected by his judgment and authority. The Pope himself, on the contrary, by favouring those who had at his instigation inserted both superstitious and ill-suited testimonials into the above-mentioned work, tried, in a not quite appropriate way, to offer individual chapters [the Responsum] that he wished to stand in their defence.’ (Noble, p.268)

Far from withdrawing their criticism of Nicaea in deference to the Pope, this high-powered group of Frankish theologians were accusing Hadrian of heresy.

A CULTURAL DIFFERENCE

I am stressing this intellectual independence from Rome – both Empire and papacy – because it brings me to the main point I want to make, which is to do with what I’ve called in the title to this talk ‘the practise of painting’ – but it really refers to the visual arts in general. This is that the difference over veneration of images expressed in the Opus Caroli and in the canons of the Seventh Ecumenical Council was not just a matter of a misunderstanding due to the bad translation of the Council’s texts; nor was it a straightforward intellectual or theological disagreement like the disagreement between the Council of Hiereia and Nicaea II. Nor was it even just a matter of politics, important as the politics were. It was also the result of a profound cultural difference, pre-existent to the intellectual quarrel, a disagreement as to the very nature and function of the visual arts. And this is a difference in principle that continues at least into the twelfth century.

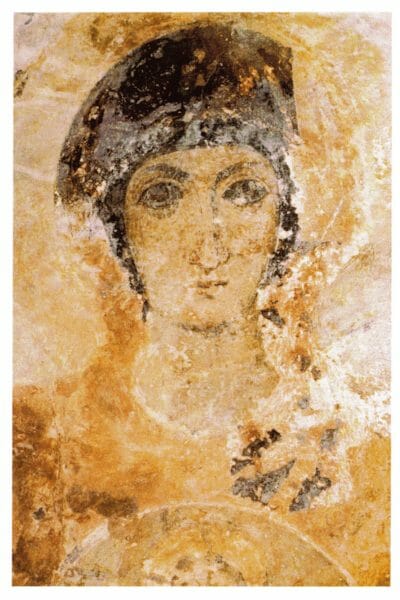

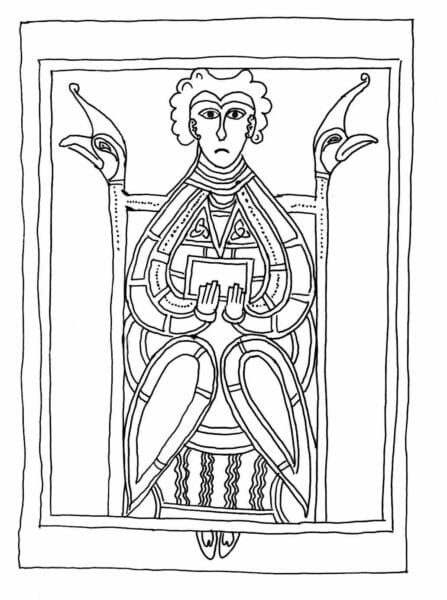

The point can be made very simply by comparing for example a painting of the virgin from the island of Naxos, usually ascribed to the seventh century and therefore before the iconoclast period, with St Mark from the seventh or eighth century Book of Dimma.

[Fig 3] Detail from a 7th century (pre-iconoclast) mural, Panayi Drosiani, Moni, Naxos. Myrtali Acheimastou-Potamianou: Byzantine Wall Paintings, Athens Ekdotike Athenon, 1994, p.34.

The point I want to make seems to me to be very obvious but, without claiming a very comprehensive knowledge of the literature, I have not seen it made except in various of the writings of Albert Gleizes. Both paintings can be described as beautiful. The first tries to convey the beauty of a person whom we might, if we are very lucky, meet coming down the street. The second has a beauty that is more intrinsic to the act of painting. The figurative elements – arms, knees, book, chair – are, so to speak, pretexts for a construction of curves beautifully organised within a rigorous rectangular frame corresponding to the overall format of the page.

Of course I am not suggesting that insular art – the art of Ireland and of northern England and southern Scotland – is the same thing as Carolingian art, but insular art enjoyed a high level of prestige in Carolingian Europe. Alcuin, Theoldulf’s older rival as educational theorist of the new Christian commonwealth, was a product of this culture. The areas of Germany that were being evangelised by Irish and Northumbrian missionaries were principle areas of expansion for the Frankish kingdom. And a number of the most important scriptoria producing insular style manuscripts were situated in territory under Frankish control, notably Echternach in modern day Luxemburg, granted by Pippin II to the Anglo Saxon missionary, Willibrord, in 700.

THE PRINCIPLE OF CLASSICAL ART – LIKENESS

The idea ingrained in the classical art of Constantinople, heir to Rome, is the idea of likeness, the copying of the external appearances of nature. The beauty is borrowed from the beauty of the external world – usually human beauty since this is not normally a painting of landscape (though there are some indications that landscape painting, and animal painting, were encouraged under the iconoclasts). The decorative elements are there to enhance the beauty of the model – it is an art that requires a model, and the idea of the ‘model’ is central to the defence of religious imagery mounted by the great opponents of iconoclasm, Saint John of Damascus and, later, Saint Theodore the Studite.

St John, for example, writing during the first period of iconoclasm in the eighth century, quotes St Athanasius of Alexandria commenting on John 10:30 – ‘I and the Father are one’ and 14:11 – ‘I am in the Father and the Father in Me’:

‘If we use the example of the Emperor’s head we will find this easier to understand. This image bears his form and appearance. Whatever the Emperor looks like, that is how his image appears. The likeness of the emperor on the image is precisely similar to the emperor’s own appearance so that anyone who looks at the image recognises that it is the Emperor’s image; also anyone who sees the emperor first and the image later, realises at once whose image it is. Since the likenesses are interchangeable, the image might answer someone who wished to see the emperor after he had seen the image, “The emperor and I are one for I am in him and he is in me. That which you see in me you will also see in him, and if you should see him, you will recognise us to be the same.” He who venerates the image venerates the emperor depicted on it, for the image is his form and his likeness.’ [5]

The theme was developed in the ninth century, during the second period of iconoclasm, by St Theodore the Studite:

‘Every man is the prototype of his own image. There could not be a man who would not have a copy which is his image … the copy is inseparable from the prototype.’ (Second Refutation of the Iconoclasts, para 6)

He quotes St Basil the Great saying:

‘the painter, the stone carver and the one who makes statues from gold and bronze: each takes matter, looks at the prototype, receives the imprint of that which he contemplates, and presses it like a seal into his material.’ (ibid., para 11)

So art is a matter of copying a model.

In the Third Refutation of the Iconoclasts St Theodore says, rather remarkably in my view, that what characterises the ‘hypostasis’, or individual reality, of a person is the peculiarity of his or her appearance not of his or her individual spiritual life:

‘When anyone is portrayed, it is not the nature but the hypostasis that is portrayed … For example, Peter is not portrayed insofar as he is animate, rational, mortal and capable of thought and understanding; for this does not define Peter only but also Paul and John and all those of the same species. But insofar as he adds along with the common definition certain properties such as a long or short noise, curly hair, a good complexion, bright eyes or whatever else characterises his particular appearance, he is distinct from the other individuals of the same species.’ (3.a.34)

So:

‘The image of Christ is nothing else but Christ, except for the difference of essence …’ (3.c.14) – the essence being the painted board. He sees the image as being quite inseparable from the prototype, comparing it to a shadow:

‘The prototype and the image have their being, as it were, in each other. With the removal of one, the other is removed’ (3.d.5) … ‘that which is not portrayed in any way is not a man but some kind of abortion … Christ must undoubtedly have an image transferred from His form and shaped in some material. Otherwise He would lose His humanity.’ (3.d.8) … ‘the failure to go forth into a material imprint eliminates His existence in human form.’ (3.d.10).

THE PRINCIPLE OF INSULAR ART – RHYTHM

The main writings in defense of images were not made available in the West but we can perhaps imagine that if the insular artists had encountered them they would have found them – particularly the passages I have just read from Saint Theodore – quite incomprehensible. Simply because they did not have the idea of ‘likeness’. It would never have occurred to them that their job was to copy the external appearances of nature. Had such an idea occurred to them I think they would have thought it an impossible task because in order to capture the external appearances of the natural world in sculpture or in painting you would have to rob it of its most salient characteristic, which is movement and change. Reading Theodore the Studite I myself found it difficult to resist the rather malicious thought that what he was writing about was not painting at all but rather photography. Christ could not have been human had it been impossible – given the right equipment of course – to take a photograph of Him.

We do not have (so far as I know) a treatise which explains in words what the insular artists were trying to do but it is quite clear from the art itself that they were working to a clearly understood philosophical and theological end. They were monks, so we can be sure that this was part of the discipline they believed would be helpful in the passage through time to Eternal Life. Both for the person working on the manuscript and for the person looking at it, this was an art of contemplation. Living in or coming from Ireland we may risk being overfamiliar with this work and losing the sense of just how remarkable it is. I hope you will forgive this effort to understand what we may think we already know.

It is in the first instance a ‘decorative’ art. We have the bad habit, when we use the word ‘decorative’ of prefacing it with the word ‘merely’. This fear of – or contempt for – the ‘merely decorative’ is not just a problem in our understanding of a large part of the history of the visual arts, it is also, I would argue, one of the reasons for the failure of twentieth century ‘abstract’ or non-representational art. We are not satisfied with decoration as the satisfaction of a simple human need – we feel the work has to ‘represent’ or ‘express’ something other than itself.

But the human need for decoration is profound and goes very centrally to our conception of what human nature is. The task is to turn a given space into a source of delight. To do so it obviously has to correspond to our human nature. A frivolous decoration implies a frivolous idea of human nature. A profound idea of human nature – for example the idea that the individual human soul is immortal and our passing life in time and space opens out into Eternity – will give rise to a profound decoration. And this is what we have to a truly outstanding degree in insular art.

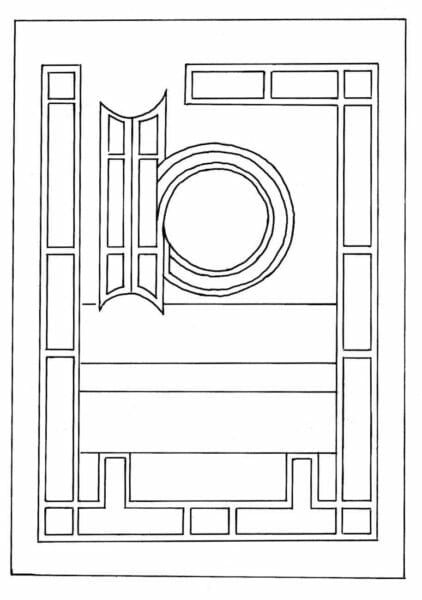

Perhaps the most important characteristic of this art is the understanding that human nature functions in both space and time. The decoration is in the first instance, as always, a structuring of space and this is largely a matter of dividing the space through the use of vertical and horizontal straight lines that stand in a clear, visually comprehensible relationship to the overall frame, usually clearly asserted.

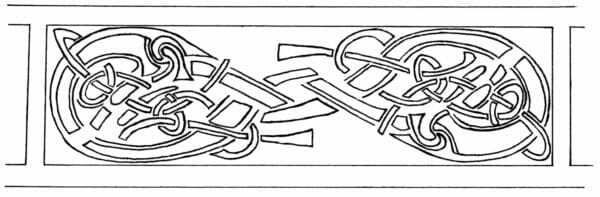

[Fig 5] Drawing based on Book of Kells (c8th/9th century), TCD Library Ms 58, folio 203r, opening page of Luke Ch 4.

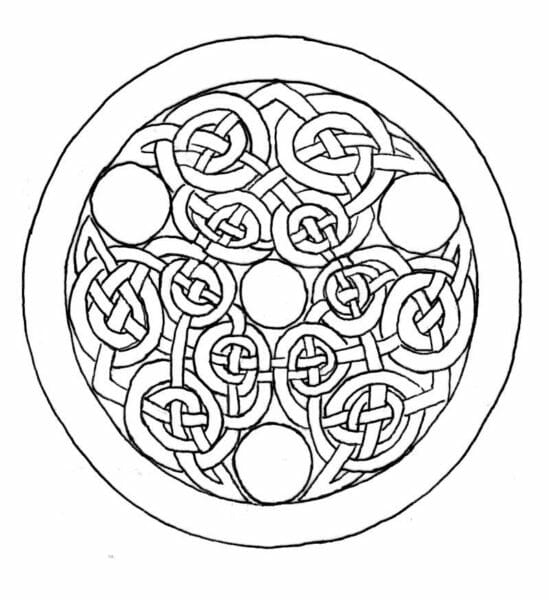

This is essentially an art of proportion and measurement, but it is still not an art of time. Time is built into the structure of the painting through the movement of the eye which has to be guided in opposition to our normal habit of jumping from one thing to another. That guided movement has to be kept within the bounds of the overall area to be decorated, within the structure given by the proportional divisions of the space. If it goes outside those limits the movement will stop. If the movement is not to stop it has to be essentially circular, it has to return on itself. The principle is expressed most clearly by a circle inscribed in a rectangle. We may be reminded of the circle inscribed in the chair of the portrait of Saint Mark in the Book of Dimma.

A circle presented baldly, however, can be seized by the eye all at once and therefore experienced as a static figure. In order for the circle to be experienced as a circular movement functioning in time it has to be slowed down and this is the function of the complications, the wheels within wheels:

the spirals:

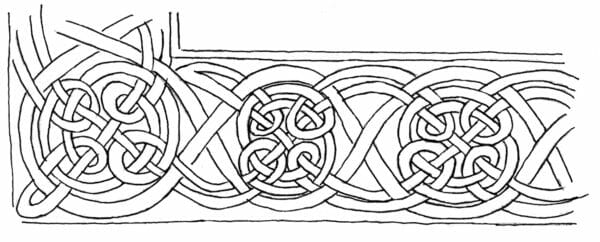

the stretching out of the circular principles into elongated arabesques which still turn back on themselves:

[Fig 9] Drawing based on detail from Book of Lindisfarne, British Library, Cotton MS, Nero, D.IV, folio 139r (opening page of Gospel of St Luke – the drawing is taken from the tail of the Q in Quoniam. I have suppressed the animal heads).

and the passing of the movement from one centre to another:

The appearance of representational shapes – animal or human heads for example – do not alter the principle I have been trying to outline but they do suggest an attitude to the appearances of the natural world which is radically different from that of classical art. This is not a scorn for the appearances of the natural world but it is a recognition that those appearances are in constant flux. They are subordinate to, indeed a product of, the overall movement. the so-called ‘primitive’ appearance of the faces, even on pages in which the figurative image is central, simply reflects the scribe’s lack of interest in anything that does not contribute to the dynamism of the decoration. A parallel may be drawn with the many sketches I have seen of Romanesque art in which the interest of the classically trained copyist has been concentrated on the figurative aspect and especially the face. The rhythmic movement which is to be found in the folds of the garments and which is the centre of my own interest and, I believe, that of the original artist, has been rendered in a very casual, slapdash manner.

I said at the beginning of this discussion of the insular manuscripts that there was no treatise to explain clearly what the monks who created them thought they were doing. There are, however, indications that the action of time would have been very much on their minds. Leaving aside the elementary religious emphasis on the transitory nature of the world, this is the period when Augustine of Hippo was coming into his own as the Latin Father par excellence. The eleventh book of Augustine’s Confessions contains a reflection on time which, Augustine says, ‘is coming out of what does not yet exist, passing through what has no duration, and moving into what no longer exists.’ Boethius’s treatise On Music is largely concerned with rhythm, which is to say the organisation of time. And the great work of John Scotus Eriugena, the ninth century De Divisione Naturae is also largely a reflection on time, for example his discussion of how time destroys the categories by which Aristotle tries to define reality. [7] Classical art could be described as Aristotleian, respecting the categories. If we imagine what an art based on the arguments of Scotus Eriugena would look like, we may arrive at something resembling insular art.

THEODULF AND A NON-INSULAR WESTERN ART

In classical art, on the one hand, and what I would call the ‘rhythmic’ insular art on the other, we have two extremes, each of which invites us to take the art seriously as a religious act. Centuries of classical culture enabled St John of Damascus and, in a more extreme form, St Theodore to argue for an ontological connection between the ‘prototype’ (the saint, Christ, the Virgin) and the painted or sculpted likeness, an argument which, I have suggested, would have made no sense to the insular artists for whom the sacredness of the art lies more in the act, in time, by which it is made and the analogous act, in time, of looking at it. The one, we might say, is an art of veneration, the other an art of contemplation. Where does that leave the non-insular art of Carolingian Europe?

When I first proposed to talk on this subject I had hoped to be able to demonstrate the existence of a distinctive Carolingian art which tried, more or less successfully, to fuse the two, preparing the way for what I would regard as the successful fusion two centuries or so later in what is called ‘Romanesque’ art. I also hoped that the Opus Caroli, written in reaction to the classical art of Nicaea II, would indicate awareness of the alternative values embodied in the insular work, even that it might have been the treatise on insular art we need so badly.

The Opus Caroli has not yet been translated into English but on the basis of Noble’s account it seems unlikely that such a case can be made. We might regret that it was not written by Alcuin, a product of insular culture, but by Theodulf, a refugee from Visigothic Spain. To judge by the detailed account given by Noble it is largely an argument against taking the visual arts too seriously. The approach resembles in some ways a Protestant attitude to illustrations of Bible stories. Religious imagery can be helpful but it is not necessary and certainly should not be regarded as an object of veneration nor is there any indication that the organisation of shapes and colours can be seen as a useful focus for religious contemplation. Theodulf insists that the Christian mysteries must be contemplated in the heart not through the eyes.

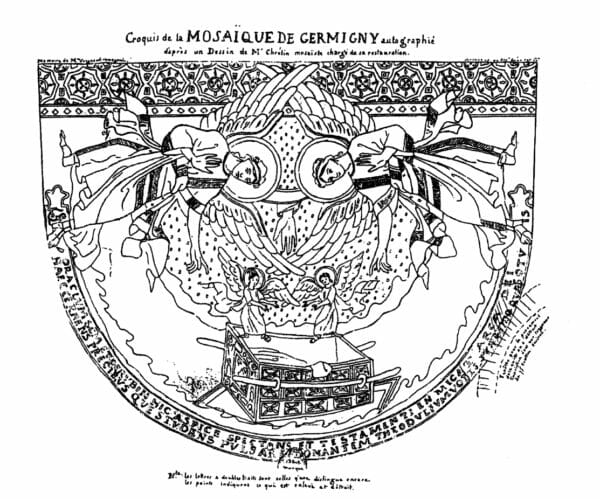

But Theodulf, one of the finest poets of his age, cannot be accused of lacking an aesthetic sense and it happens that we do have an important work of art associated with him – the mosaic in his private chapel in Saint-Germigny-des-Pres.

This has been analysed by Ann Freeman and Paul Meyvaert, who argue that it is based on works Theodulf would have seen in Rome at the time of Charlemagne’s anointing in 800 as Emperor in the west; and that it engages with the issues raised in the Opus Caroli – they suggest indeed that it could be interpreted as a consequence of Theodulf’s frustration at the suppression of the Opus, a very ambitious work that could have played (and perhaps indirectly did play) a major role in defining the distinctive character of Western Christianity. [8]

In the confrontation I have outlined between rhythmic art and classical art, the mosaic is very definitely on the classical side, but the apse space is not used to give us a Christ or a Virgin or any figure offered for our veneration. It shows the ark of the covenant and the cherubim which Freeman argues follows a scheme outlined in Bede’s Treatise on the Temple. The fact that God ordered Moses to depict the cherubim was an argument frequently used by the iconophiles to justify religious imagery. It is an argument ridiculed in the Opus saying no comparison can be made between a direct order from God and the whims of an individual artist. Without going into the details of Freeman’s analysis, her broad conclusion is that this is a serious work of art but its seriousness lies neither in veneration nor in wordless contemplation but in the illustration of a highly sophisticated intellectual argument. Recent research suggests a similar concern (illustration of an intellectual/theological thesis rather than presentation of an image for veneration) with regard to the purely figurative side of the decoration in the insular MSS. [9]

[Fig 11b] Germigny-des-Prés, apse mosaic, 9th century, after a drawing by Théodore Chrétin, after Vergnaud-Romagnesi: Addition à la notice sur la découverte en janvier 1847 de deux inscriptions dans l’église de Germigny-des-Prés, Orléans, 1847 [copied with the caption – hence the ‘after’s – from Ann Freeman and Paul Meyvaert: ‘The Meaning of Theodulf’s apse mosaic at Germigny-des-Prés’, Gesta, Vol 40, No 2 (2001), p.130.

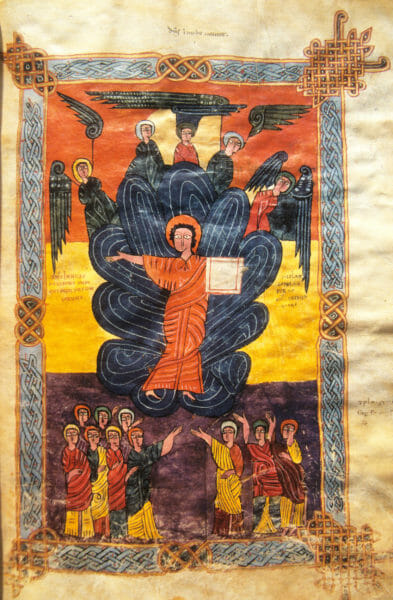

It is not possible here to discuss the larger question: was there (as is sometimes suggested) a Carolingian fusion between the two extremes of insular and classical art; and if so, was it based on a theological understanding either of the contemplative insular art or of the theory of prototype and image which was evolving in the eastern classical tradition to support the veneration of religious imagery? My own feeling is that the Opus Caroli’s somewhat dismissive attitude to the religious image – the refusal to see it as a means of entering into communion with the divine – was typical of the wider society. It is an essentially illustrative art (the outstanding example being the almost comic book illustrations to the Utrecht Psalter). The classical influence is strong but does not undergo the changes that occurred in the East to make of it an art of veneration (thereby becoming what we like to call ‘Byzantine’ art). The decorative side uses elements that are familiar from insular art but they have now become indeed ‘merely’ decorative, lacking the rigour and seriousness of a truly contemplative art. Nonetheless, elements of a different approach to the sacred in art – both illustrative/figurative and decorative/contemplative – were emerging, notably in Visigothic Spain.

[Fig 12a] Illustration to the commentary on the Apocalypse by Beatus (the commission to write to the seven churches), 1086, cathedral of Burgo de Osma, folio 23 (photo R. and M-J.Friedlander).

The Visigothic culture of Theodulf’s origins had, much more than the Franks, aspired to assume the classical heritage, to become Roman. It knew classicism intimately. It is perhaps worth mentioning in the present context that Visigothic Spain in the tenth century produced the most defiantly unclassical art of the Beatus manuscripts. Rather than seeing this as a ‘primitive’ art of a people who did not know classical art it would be better to see it as a quite conscious rejection of classical art by a people who knew it very well. It is the marrying of a non-classical figuration with an overall decorative/contemplative rhythm that will characterise the distinctive genius of Romanesque art.

[Fig 12b] Illustration to the commentary on the Apocalypse by Beatus (Christ’s appearance in the clouds), 10th century, Musei Diocesá de La Seu d’Urgell, folio 19r (photo R. and M-J.Friedlander).

CONCLUSION: VENERATION AND [OR?] CONTEMPLATION

To conclude. The promise of the image of the Saint presented for veneration is that it helps us enter into a personal relationship with the Person (Saint, Christ, Mother of God) represented. The idea of ‘likeness’ is important (hence the importance of the stories of King Agbar and the icon not made by human hands, or of Saint Luke painting the Mother of God, by which the likeness of Christ or of the Mother of God is given authority). Since the icon in a manner of speaking IS the Person, we approach it as we would the Person, with awe, with lowered eyes. We do not paw over the painting with our eyes, delighting in the play of lines and colours even if, as may be the case, these may be rich and satisfying.

The rhythmic painting is approached in a quite different spirit. Here we are invited to look attentively, to enter into the play of lines and colours. The promise of the painting is that it opens up to the fulness of our human nature as it functions in space, time and ultimately (I would argue) Eternity. It is a mirror raised before us to remind us of the fulness of our human nature as the image of God. As such it too has a religious function.

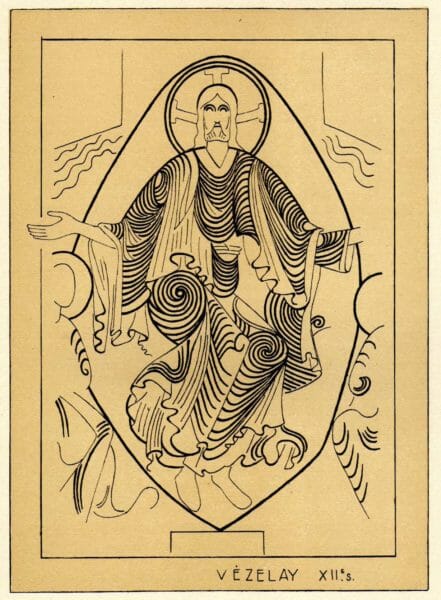

Can these two religious functions be reconciled in a single work?

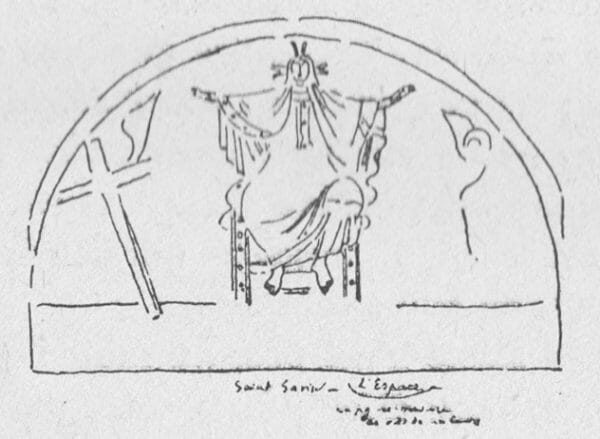

[Fig 13]: Illustration from Albert Gleizes: La Forme et l’Histoire, Jacques Povolozky, Paris, 1932, p. 19.

Figure 13 is a drawing based on the tympanum of the abbey church in Vézélay. It was prepared by Robert Pouyaud as an illustration to the book Form and History by Albert Gleizes. The drawing emphasises the rhythmic side of the tympanum, the element it shares with insular art (the book delights in ridiculing the argument of the specialist in Romanesque art Emile Male that the turbulence of Christ’s garments was suggested by the rough wind that blows through that part of France). Is the Christ in the tympanum an object of veneration? Do we wish to engage in an act of veneration, or do we wish to stare at the whole movement of the tympanum, allowing it to raise us to an act of silent contemplation? I am not proposing an answer to this question, only suggesting that it is a question worth pondering.

Notes:

[1] Jean Chevalier: ‘L’Oeuvre d’Albert Gleizes’ in L’Art de l’Église. Bruges, 1954. Quoted in L’Art Sacré d’Albert Gleizes, exhibition catalogue, Caen, 1985. Pages not numbered, comment on exhibit no. 24.

[2] Albert Gleizes: La Forme et l’Histoire, Jacques Povolozky, Paris, 1932. p.376; ibid: Art et Religion, Art et Science, Art et Production, Editions Présence, Chambéry, 1970. English translation with introduction and notes by Peter Brooke, as Art and Religion, Art and Science, Art and Production, Francis Boutle publishers, London, 1999. Reference to the Council of Frankfurt p.50 of the English translation.

[3] Thomas F.X.Noble: Images, Iconoclasm and the Carolingians, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2009.

[4] The ‘Roman’ character of ‘Byzantium’ is discussed in a polemical but nonetheless informative manner in John S. Romanides: Franks, Romans, Feudalism and Doctrine – An interplay between theology and society, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, Brookline, 1981.

[5] In the documentation appended to the ‘Third Apology of Saint John of Damascus against those who attack the divine images’ in Saint John of Damascus: On the Divine Images, translated by David Anderson, St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood NY, 1980, p. 101.

[6] Saint Theodore the Studite: On the Holy Icons, translated by Catharine P. Roth, St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood NY, 1981.

[7] Johannis Scotti Eriugenae: Periphyseon (De Diuisione Naturae) Liber primus, edited and translated by I. P. Sheldon Williams (with Luwig Bieler), Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin, 1968. Discussion of the categories pp.85 et seq.

[8] Ann Freeman and Paul Meyvaert: ‘The Meaning of Theodulf’s apse mosaic at Germigny-des-Prés’ in Gesta, Vol 40, no. 2 (2001), pp. 125-139.

[9] See e.g. Jenifer Ní Ghrádaigh: ‘Audience, visuality and naturalism: depicting the Crucifixion in tenth-century Irish art’ in J.Rutherford and D.Woods (eds): Mystery of Christ in the Fathers of the Church, Dublin 2012.

[…] article I have written has been published by the online Orthodox Arts Journal under the title The Seventh Ecumenical Council, the Council of Frankfurt and the Practice of […]

Thank you very much, Fr. Silouan, for bringing this article to our attention. Dr. Brooke’s observations about Byzantine versus Insular art are spot-on, in my opinion. Though I have always felt something along these lines when I look at Insular art, I have never had the clarity of thought to put it into words. I am most grateful for this article, as it has helped me make sense of things I had understood in my heart, but not quite in my mind.

In particular, I look forward to applying this mode of analysis to decorative ornamentation in iconography. Occasionally one sees icons painted in the canonical Eastern style, which also incorporate decorative interlace. I refer, for instance, to so many icons produced in the Russian Empire circa 1900, which often have neo-Slavonic interlace decoration painted around the border. Or to modern icons of Celtic saints, where vestments and borders bear Kells-like ornament. I have always wanted to like such fusions. As a decorative artist and an Anglophile convert to Orthodoxy, the idea of fusing Byzantine iconography with insular decoration is obviously appealing. But I have usually felt that these icons are problematic. If the ornamentation is well done, and has the kind of dynamic movement typical of insular art, it distracts from communion with the figure in the icon. It pulls the eye away from the face, and into the puzzle of decorative contemplation. On the other hand, the ornamental details that more traditionally belong to Byzantine art tend to be more static. We can understand them fully in a single glance. I have often wondered why Byzantine ornamentation is so boring compared to Romanesque ornamentation, but this article has brought much clarity to the question. Static ornamentation, is, perhaps, a necessary complement to the spiritual immediacy of Byzantine art.

Just 1 brief word Glizes was the 1st person to use the term cubism; he was NOT the founder of the movement known as cubism although he may have been the “self proclaimed” founder .

The term ‘Cubism’ was first used by people hostile to the movement as a term of ridicule, in particular Louis Vauxcelles, who also devised the term ‘Fauvism’, though Henri Matisse had exclaimed ‘Tiens, les petits cubes’ or something like that when he saw the first Cubist paintings of Georges Braque in 1908. In 1912, Gleizes and Jean Metzinger (partly in an effort to distinguish themselves from the Futurists who had ‘invaded’ Paris earlier in the year) published a sort of manifesto under the title Du “Cubisme”. The inverted commas are important and they begin by saying they’re adopting the term because it’s become generally accepted not because it adequately describes what they’re doing. Gleizes never claimed to be the founder of Cubism. On the contrary he always insisted that there was no individual founder, that it was a collective movement formed through the coming together of two separate currents – Picasso and Braque on the one hand, himself, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger on the other. The historian Daniel Robbins coined the term ‘Epic Cubism’ to characterise this latter group – they went for big subjects in contrast to the intimate still life subject matter of Picasso and Braque. Gleizes’s view is now – at long last – becoming generally accepted, for example in the introduction to the Cubism Reader by Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighton (2008) and in the essay by Serge Fauchereau (previously a champion of the Picasso-centric view) in the catalogue of the 2012 Gleizes-Metzinger exhibition in Paris (which also as it happens contains an essay by me!).

Actually, Vaucelles coined the term “tubism” to describe Leger’s work. He only used the word cube to describe the pictures he saw by Braque etc. and he did not apply it to a general movement. These small omissions of fact smack of a rewrite of history. LOL Anyhow no mention of Gris and Mannerist cubism and then there werethe contemporary Russian practitioners. Conclusion: IMHO and many others; cubism was the most important art movement of the 20th century and still to this day over a century later, remains a viable and potent influence, Glizes was indeed part of a much bigger picture.

I don’t understand what the problem is here. My article wasn’t about early Cubism. All I said about Gleizes was that he was a ‘twentieth century French painter.’ Father Silouan called him, and I of course, agree, ‘a father of Cubism.’ He didn’t say he was THE father of Cubism. But insofar as the article was about Gleizes it concerned the later development of his thought. If anyone wants to know my views on early Cubism and the relations between the different painters, including Juan Gris, I have a long essay, originally intended as the introduction to a new edition of Du “Cubisme”, at http://www.peterbrooke.org.uk/a%26r/Du%20Cubisme/contents I have no problems with John’s view that as far as the history of Cubism is concerned, Gleizes is ‘part of a much bigger picture’

…. apologies for my mistaken impressions although calling him “a” father of cubism is really overstating things anyhow excellent article albeit a bit dense for moi …and thanks for the link … All the best …

I would really appreciate Jonathan Andrew or Fr. Silouan picking up where this article leaves off, or even Dr. Brooke himself.

I would like to know a LOT more about the transition from insular pre-Carolignian iconography to what we call Romanesque iconography. I think further discussion on this topic is essential for any initiative to develop towards a contemporary indigenous iconography in western cultures – do we do this by means of revisiting these medieval (I use the term loosely) periods in our western history, or do we start from where we are today? I am yet to be convinced that the way forward involves recovering the Romanesque; it may be that the 21st century is the only place we can start, and the only ground that will ‘bear fruit’ is following the roots that are part of the continuity of orthodox faith.