Similar Posts

In a recent panel discussion on music for the Orthodox Christian Studies Center of Fordham University, composer Benedict Sheehan made the observation that the publication of musical anthologies tends to solidify and codify generational snapshots of particular traditions, carrying authoritative weight for those who use it as a resource.

These anthologies… put on the page a thing that is always in the process of evolution… A book gives us the illusion that things have always been that way… and that some of these things have the stamp of approval from the Church in some… official capacity.”

Sheehan cited the 1969 The Divine Liturgy Liturgical Music edited by Fr. Vladimir Soroka (the “Blue Book”) and the 1982 The Divine Liturgy compiled by David Drillock, Helen Erickson, and Fr. John Erickson (the “Green Book”) as two different generational examples for the Orthodox Church in America (OCA); in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese (GOA) there is the 1982 (revised 2018) Divine Liturgy Hymnal (the so-called “Green Book”) and its forbears, the 1944 Armonike Leitourgike Ymnodia by George Anastassiou and the 1956 Iera Ymnodia compiled by Christos Vryonides. Similar publications exist for the Antiochian Archdiocese as well, and Sheehan himself is the editor of such an anthology, the 2015 A Common Book of Church Hymns: Divine Liturgy for St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press.

For the celebration of Easter, the standard English-language anthology for several years has been the 1980 Pascha: The Resurrection of Christ, edited by Drillock, Erickson, and Erickson for SVS Press, which contains English adaptations of the most commonly sung settings in the Slavic repertoire. Along with the recording from SVS’ chapel titled Pascha: Hymns of Resurrection, which includes of a number of the works contained in the book, this anthology has had a widespread, almost determinative, influence on the Paschal celebrations of many Anglophone parishes for decades.

Now, in 2021, there are two new anthologies of Anglophone Easter repertoire that are, in their own way, generational responses to the SVS Pascha book. These are: Great and Holy Pascha: The Resurrection of Christ (Musica Russica, ed. Vladimir Morosan), and The Mystic Pascha (Dynamis Liturgical Collective, ed. Samuel Herron). Each is a snapshot of different branches of musical development in Anglophone Orthodox Christianity over the last forty years — Great and Holy Pascha is representative of an eclectic approach to Orthodox music, and The Mystic Pascha is representative of the rapid expansion of English-language production of Byzantine chant. This does not mean that there is no overlap between these collections; on the contrary, overlapping compositions are included, and they are informative for the marked difference of approach within the same idiom that they represent.

Morosan describes the generational shift for Orthodox liturgical music between the publication of SVS’ Pascha: The Resurrection of Christ in the preface for Great and Holy Pascha as follows:

1) a greater awareness, by means of audio recordings on the Internet and in other media, of various national traditions;

2) the planting and growth of new Anglophone mission parishes, chiefly in North America, but also in the United Kingdom, Australia, and elsewhere;

3) the trend away from large parish choirs of mixed voices to smaller ensembles of varied voicing.

Accordingly, Great and Holy Pascha is a wonderfully useful resource for parish choirs that have a flexible membership and aggregate skill set, as well as ever-shifting pastoral musical needs, thus requiring an equally flexible array of available musical options. As such, it also serves as a representative snapshot of a segment of the choral activity in our churches, driven by the established generation of musical leaders across the American jurisdictions — Morosan himself, Anne Schoepp, Jessica Suchy-Pilalis, Tikey Zes, Kurt Sander, and others. At the same time, the volume also includes English adaptations of the Slavic masters such as Kastalsky, Arkhangelsky, et al.

Certainly the transnational situation that technology has contributed to, as well as the growth of English and the shrinking of large polyphonic choirs, has in some cases inspired the more lightweight and flexible small ensembles that embrace a plurality of repertories, just as Morosan relates. However, in other cases, these circumstances have produced specialists in, as well as evangelists for, particular repertories. Dynamis Liturgical Collaborative’s The Mystic Pascha is representative of this branch of activity, being a more specialized collection that is intended for the increasingly-common situation of a parish with a dedicated Byzantine choir.

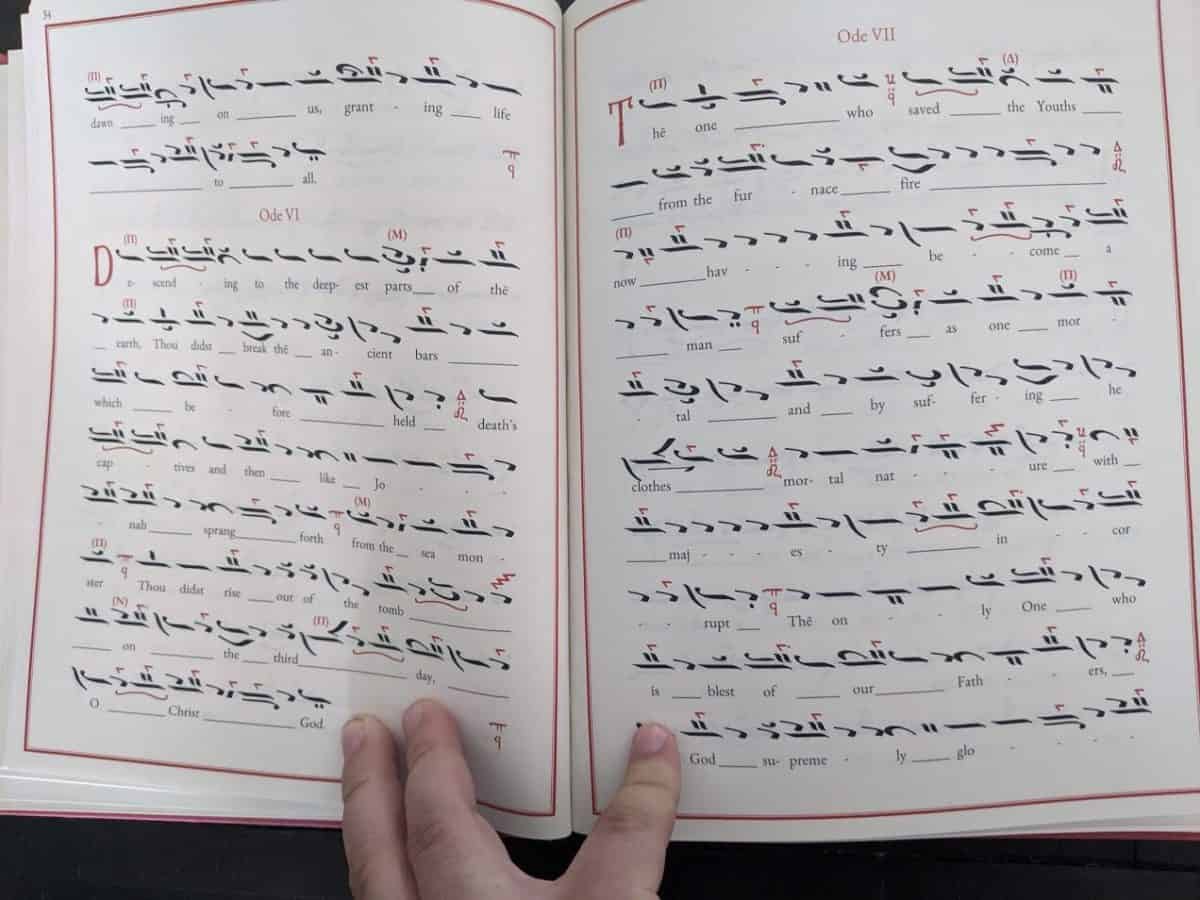

The scores in The Mystic Pascha are all in Byzantine notation, and the idiomela are largely newly-composed and previously-unpublished by living composers. This roster includes Herron himself, John Michael Boyer, Ioannis Arvanitis, Gabriel Cremeens, Phillip Carl Phares, and others. Additionally, the prosomoia and canons are metered for the melodies found in the standard published Heirmologia; the notes credit this to the collective work of the Ensemble, including everybody mentioned above as well as contributors such as Peter George and Robert Seidel. Overall, this volume represents a very different kind of snapshot from Great and Holy Pascha — one that would have been unthinkable even ten years ago.

The Paschal canon is a centerpiece of both publications, and an intriguing point of both overlap and contrast. Great and Holy Pascha contains five separate realizations covering different choral scenarios — a Byzantine arrangement by Jessica Suchy-Pilalis, Russian “Greek” chant in 2 and 4 parts as well as in an “abbreviated” form, and then Obikhod chant following the arrangement of Nikolai Bakhmetev (+1884). Each version employs the unmetered translation in use by the OCA, and the settings reflect this; the Russian settings rely on the text arranged according to stock phrases, with the text occasionally being made to fit through declamation on a reciting tone. The Byzantine setting is through-composed; each troparion is given its own melody, with “thee/thou” variants presented alongside “you/your” in the score. In addition, it is presented entirely in staff notation (one Byzantine composition elsewhere in the book, the Paschal doxastikon, is presented in both staff and neumatic notation). Composer Jessica Suchy-Pilalis also references the option in Byzantine practice to sing the katavasies, the repeats of the heirmoi that close out each ode, “in a more ornate or ‘slow’ style.”

By contrast, the setting of the Paschal canon as found in The Mystic Pascha is entirely in Byzantine notation, and employs a metered translation that can be sung to the canon’s established model melodies. (See this article for an exploration of the issues surrounding metrical translations.) The score includes written out versions of the slow katavasies rather than leaving them to the interpretation of the cantor. At the same time, there is a departure here that the book’s editors acknowledge; while The Mystic Pascha for the most part uses a “modern” English register, the metrical translation of the Paschal canon is at least in part the contribution of an anonymous monastery that insisted on retention of a “thee/thou” register as part of the terms of publication.

Taken together, these two publications represent rich and complex musical possibilities for today’s Orthodox parishes, and both books are more than worthy additions to your English music library. If you can only read one notation, it is worth your time to learn to read the other so you can access both publications. Great and Holy Pascha is a wonderful “zoom-out” of the crazy-quilt variety of Anglophone Orthodox liturgical music; The Mystic Pascha is an excellent “zoom-in” on the current state of English-language composition for the Psaltic Art. Both should be considered standard collections — with the caveat that there remains a great deal of circulating English repertoire that is standard, more or less, but as-yet unpublished in book form.

You can find Great and Holy Pascha at www.musicarussica.com; The Mystic Pascha is available at www.dynamisensemble.org.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

Having grown up with the faithful-to-the-original, but profoundly non-English, translation “Holy and Great Pascha,” the change to “Great and Holy Pascha”–the order required by the canons (and metrics) of the English language–strikes me as itself epitomizing a momentous step in the flowering of an Anglophone Orthodoxy.

How beautiful it is to watch this naturalization.