Similar Posts

Editor’s Note: Our readers may remember the piece we published previewing the Hexaemeron Inc. workshop on ecclesial embroidery. This piece is a follow-up, now that the course has been completed.

“And all the women that were wise-hearted did spin with their hands, and brought that which they had spun, both of blue, and of purple, and of scarlet, and of fine linen.” (Exodus 35: 25)

Six women who had never met before formed a special bond during their six days spent together, September 27 to October 3, 2012, at the Living Waters Catholic Refection Center in Maggie Valley, NC. Their closeness grew out of the struggle shared in bringing a master embroiderer to the United States from the Ukraine to teach a course in the ancient art of pictorial embroidery.

Olga Fishchuk is a practicing ecclesial artist living in Kiev. She is one among a special set of graduates from the Moscow Orthodox Theological Academy’s Pictorial Embroidery Department of the Icon Painting School, which is housed within Holy Trinity-St. Sergiev Posad Lavra. The department only accepts two or three students a year.

Hexaemeron non-profit organization scheduled Olga to lead a group of American needle workers in this ancient tradition that so few artists still practice. The class was fully rostered by early June, but Hexaemeron faced a crisis of good faith when Olga’s visa was twice denied in July. Determined to prevail, the women solicited the aid of their respective congressmen and senators in mid-August. A third visa application, expedited by legislator support, was successful.

Why was Olga’s course so important to the needle workers who came to Maggie Valley? As Marilyn Shesko, one of the participants, put it, “I have been searching for a teacher of ecclesiastical embroidery for more than twenty years. In my search, I consulted with two past presidents of the Embroiderer’s Guild of America, neither of whom knew of anyone in this country that had knowledge of this form of embroidery. While in London, I booked a consultation with an expert in England’s Royal School of Needlework, who was equally unable to offer any suggestions of where such training might be obtained.”

Important to Orthodox Christians and to all Christians, as well as world art, is the long history of ecclesial embroidery that is contiguous with the work of artisans who adorned the Tabernacle in the Wilderness and wove the vestments for the High Priest Aaron.

“And of the blue, and purple, and scarlet, they made clothes of service, to do service in the holy place, and made the holy garments for Aaron; as the LORD commanded Moses. And he made the ephod of gold, blue, and purple, and scarlet, and fine twined linen. And they did beat the gold into thin plates, and cut it into wires, to work it in the blue, and in the purple, and in the scarlet, and in the fine linen, with cunning work.” (Exodus 39: 1-3)

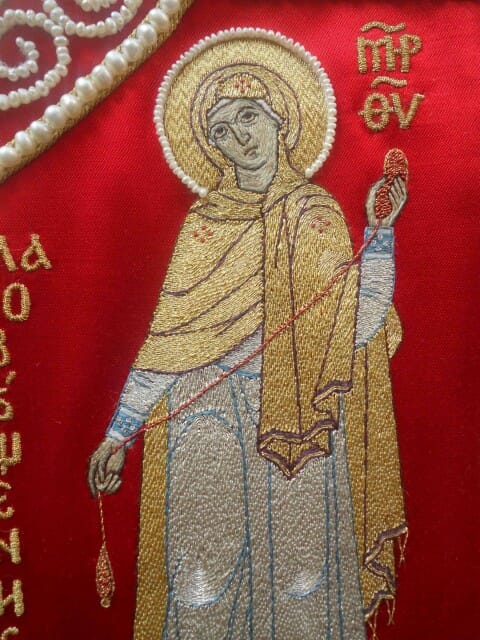

Very early, the Church took up the sacred work of skilled needlework artists described in the books of Exodus, Sirach and Proverbs. The oldest extant piece of church embroidery with a facial image dates from 4th century AD, though we can surmise that earlier pieces have perished. Pictorial embroidery in the Byzantine Era developed into a form of high art along with iconography and church architecture. Embroidered icons had many uses. Besides the epitaphios carried in Holy Week processionals, fabric rendered iconography had a portability that made it ideal for holding services near battlefields and for evangelistic missions to pagan territories. Entire iconostases were created out of textiles that could be rolled up for ready transport.

Byzantine embroidery was also prized in Western Europe as shown by the so-called Dalmatic of Charlemagne purported to be commissioned or given as a diplomatic gift for Charlemagne’s coronation in 800. The work, now stored in the Vatican treasury, is actually a patriarch’s sakkos (tunic) that Constantinopolitan artists created in the 14th century. On the front of this fabulous garment, Christ Enthroned is embroidered in silk and gold threads. He is encircled by angels above His head and saints, kings, patriarchs, bishops, monks and nuns at His feet. On the back of the sakkos the Transfiguration and Ascension are depicted.

During the Palaiologan Renaissance [1260 – 1453], the highest examples of Byzantine embroidery arts were created. A small number of great epitaphios have survived from this period. One of the most remarkable is the 14th century Epitaphios of Thessaloniki kept in the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki. It is very large, 2m x 72 cm, and consists of three parts. Christ’s body flanked by His grieving mother, Mary Magdalene and angels, forms the central piece. The communion of the Apostles is presented in two parts: the communion with wine on the left of the epitaphios and communion with bread on the right. This detail of angels grieving the crucified Savior gives a glimpse of the anatomical faithfulness of the needle workers’ art and their mastery of conveying the tenderest emotions with silk threads.

Long before the Eastern Christian Empire succumbed to Islamic destruction in the mid-15th century, Byzantine styled embroidery organically passed to the nascent Slavic cultures of Kiev and Rus and to the emerging Balkan nations of Serbia and Bulgaria as a result of trade and missionary journeys. When Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, many painters and architects took refuge in Russia. “They were very highly valued by noble customers, and local artists imitated their art and called them teachers”, says Olga.

The first church embroidery studios in Russia appeared in the 11th century under the aegis of noble women who provided for workshops filled with embroiderers. Olga describes how the workshops were organized, “Studios were generally led by the mistress of the house, a queen or a princess herself. There were embroiderers – specially trained female serfs, sometimes as many as 50 – 80 skilled women working in the royal studios at the same time.” By the 18th century needlework art in Russia began to wane as the aristocracy became influenced by secular entertainments introduced through contact with Western Europe.

Ecclesial embroidery is still essential to and inseparable from the majesty of Orthodox temples and the divine services of the Church. Vestments of hierarchs and priests, epitaphios, chalice veils, altar cloths, banners, and podia for icons are among the many ceremonial pieces where embroidery is used. Most of this work is now machine executed, both because there are few teachers with an educated knowledge of the art and because there are few women who choose a vocation in pictorial embroidery.

Inge Wierda, an art historian and Russian art specialist who teaches at several universities in the UK and the Netherlands, organized an exhibition of Olga’s works in Amsterdam in 2010. According to Dr. Wierda, “Traditional ecclesiastical pictorial embroidery is a unique art form. In the Middle Ages it was as popular as icon painting. Embroideries were favorite collecting items and can be found in museums all over the world. Nowadays, very few people, mostly found in Russia and the Ukraine, master and practice this painstaking and time consuming hand work. Fast and cheap machine embroidery is replacing unique hand work all over the world. Therefore, it is of great importance to support, develop and spread the art of ecclesiastical pictorial embroidery in ancient style.”

In reality there is little patronage to support the art, given the secular structure of contemporary society worldwide. Based on an hourly-wage economy, the amount of time needed to produce even small items for liturgical use means that the needlework artist cannot earn a fraction of the minimum wage. There is no lack of needle workers, however, and they are passionate about their art. The Embroidery Guild of America alone boasts more than 10,000 members. Several of the women who came to Maggie Valley to learn from Olga were artists with years of experience in a broad range of stitching traditions. Their enthusiasm for the instruction and information Olga imparted during their six days together may ultimately play a part in realizing Olga’s mission to “spur a revival of the ancient art of ecclesiastical pictorial embroidery.”

“Olga’s classes are the fulfillment of a long-standing dream,” Marilyn Shesko says. “Her embroideries are stitched to the high standard of museum pieces from the 14th-17th centuries, and she is prepared to teach her students to embroider to that same standard. At the same time, she is quite willing to share methods for simplifying the work so that larger-scale items can be completed by a single person rather than requiring an entire workshop of embroiderers. While the stitches used are found in many forms of Western embroidery, they are rarely taught at this fine scale and with this very high level of accuracy.”

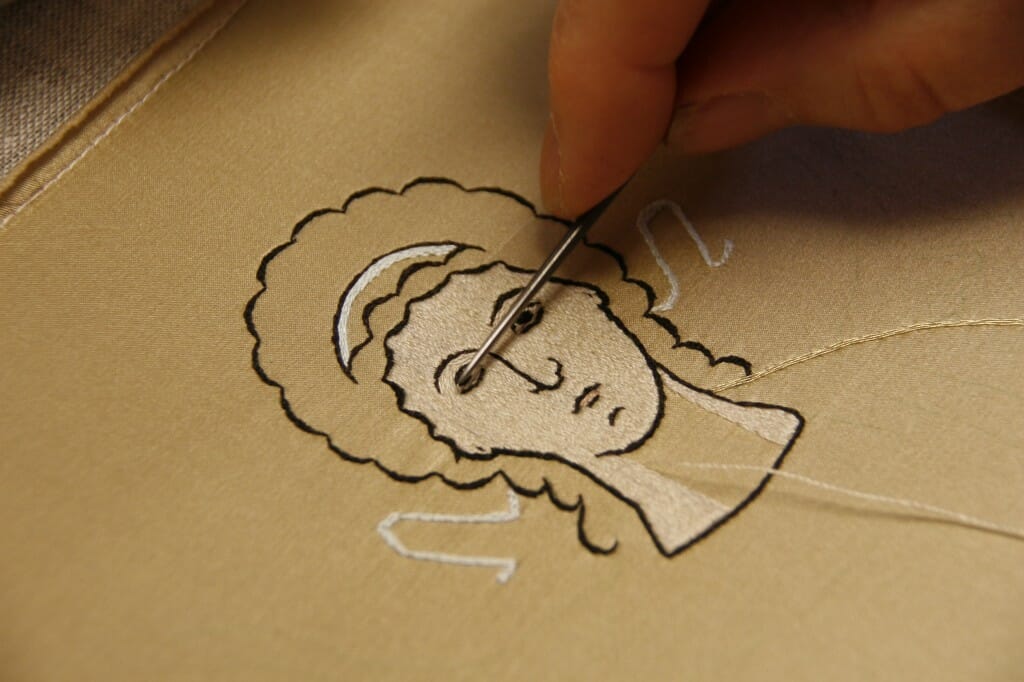

The needle workers’ room at Maggie Valley was always quiet when I entered to observe and take pictures. “The sign of a good class”, one of them noted. Even more than painting, needlework is a communal art. Company is a balm for the long hours of concentrated labor. Yet, silence reigned. Perhaps, because every stitch, each one smaller than a fourth of a grain of rice, must be placed with great precision. Correcting an errant stitch discovered late multiplies the project by many precious hours of undoing and re-stitching.

The women worked late into the night. “The wise hearted did spin with their hands …” But work with gold thread was always done in the morning when natural light was available. “Artificial light is very hard on the eyes when performing gold work,” Olga says. The eyes and hands of the wise-hearted must be carefully guarded.

Olga Fishchuk and Ksenia Pokrovsky share a teaching break in the icon painting workshop that ran concurrently with the pictorial embroidery class.

Donna Halpin, who took the class and is a certified needlework judge for both the American Needlepoint Guild and The National Academy of Needlearts, said, “This class is one of the few opportunities in America, if not the only opportunity, to learn the traditional technique of pictorial embroidery of icons and how to do so with museum quality stitching.”

Olga is scheduled to lead five embroidery classes in 2013. For dates and places, visit: hexaemeron.org.

Note: Background Information shared in this article was based on three lectures about the history of embroidery that Olga Fishchuk delivered as part of her course. Olga plans to publish her research.

It is wonderful to hear everything worked out. Congratulations to all in making this possible.

[…] Oct 16th 11:28 amclick to expand…Rescuing the Art of Ecclesial Embroidery https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/rescuing-the-art-of-ecclesial-embroidery/Tuesday, Oct 16th 11:00 amclick to expand…St. Joseph's Seminarians and Monsignor Visit Seminary […]

Thank you, Jonathan, it was exhausting work engaging US Immigration and the State Dept. Special thanks to Ellie Sutter, retired senior foreign diplomat, and Senator Scott Brown for their steadfast assistance. We must start work on your visa now.

You just keep surrounding yourself with foreigners.;) Hopefully diplomatic relations between the US and Canada are a bit smoother… it should just be a question of going through the motions with enough time to spare.

Jonathan, I must correct Ellie Sutter’s title. She is a retired Senior US Diplomat.

[…] Read about the efforts of Olga Fishchuk, a master embroiderer from the Ukraine, to “spur a revival… Like this:LikeBe the first to like this. Blogroll […]

Thank you- it is incredible!

I too have been looking for instruction in this art. It is great to see that something is happening. Well done. I would love to see more pictures of the work done. And more writing on embroidery would be great, too.

Thank you, Karen. You can see many beautiful pieces on Hexaemeron’s website: http://www.hexaemeron.org/#!embroidery-store/c1dhe

There is wonderful chapter on ecclesiastical embroidery by Warren Woodfin in the companion volume to the 2004 Metropolitan Museum exhibit: Byzantium: Faith and Power

Evans, Helen C (editor) Byzantium Faith and Power (1261-1557. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art (2004, March 11), pp 295-8: “Liturgical Textiles” by Dr. Warren Woodfin; Queens College, NY.

http://www.metmuseum.org/research/metpublications/Byzantium_Faith_and_Power_1261_1557?Tag=&title=&author=&pt=0&tc={F52F45EC-2E28-4BC3-96B6-879A33F0B139}&dept=0