Similar Posts

Editorial note: This is the third part of a series on the artistic path and iconographic legacy of Saint Sophrony the Athonite (1896-1993) as seen through a collection of monographs written by Sister Gabriela, a member of his monastic community in Essex, England. The previous articles, Seeking Perfection in the World of Art can be found here and ‘Being’: The Art and Life of Father Sophrony can be found here.

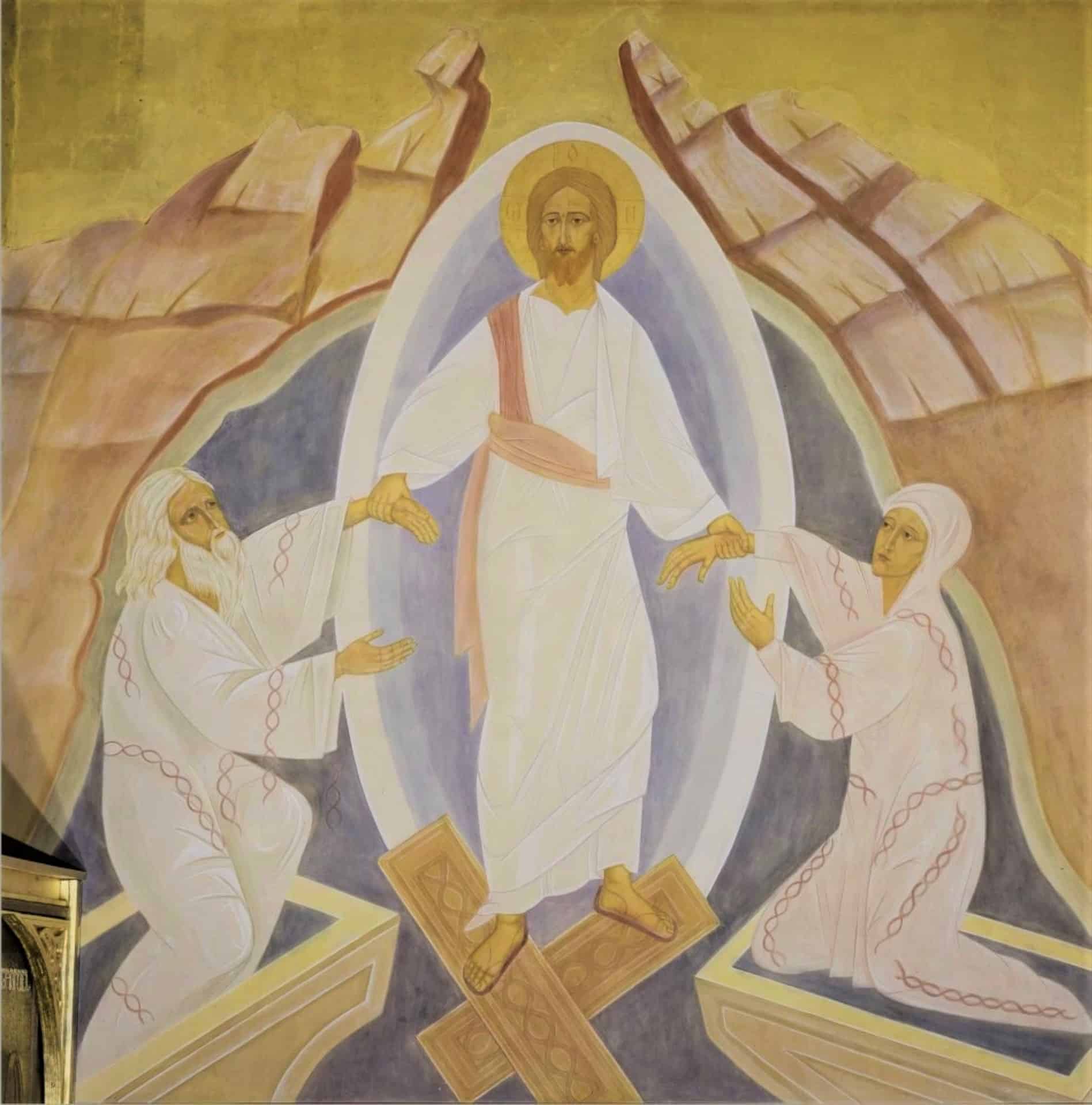

The Resurrection, mural in oil paint on gypsum plaster by Saint Sophrony. South wall, St Silouan’s Chapel, Monastery of St John the Baptist, mid 1980s.[1] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“On the icon of the Resurrection Adam looks at his Creator with astonishment, Eve also, but not so much, she is a bit troubled. But we will all be astonished on that day.”[2]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

Introduction:

Painting as Prayer: The Art of A. Sophrony Sakharov is the third book of Sister Gabriela’s writings on the iconographic legacy of Saint Sophrony the Athonite. It is a handsome, large-format publication[3] presenting a glorious panorama of photographic highlights from the saint’s extensive body of iconographic and design work. Beginning with some fascinating introductory thoughts on creativity, freedom and the icon, she then explicates Saint Sophrony’s approach to iconography, which is complemented by a later chapter on his artistic techniques. The majority of the book comprises a selection of large-scale colour photographs documenting many aspects of the breadth of projects upon which he worked, from drawings and preparatory studies, murals and panel icons, to design work including embroidery, tapestry carpets, letterforms and metalwork. The images are followed by a section of detailed notes which provide additional insight and information on each of the projects. This summary will give a brief overview of the writings and will then focus on exploring and presenting some of the rich banquet of projects featured throughout the book.

Book Cover of Painting as Prayer: The Art of A Sophrony Sakharov.

Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Differing from the previous two monographs, Painting as Prayer approaches its subject from the perspective of a practicing iconographer who assisted the saint in his work. It contains numerous fascinating comments from Saint Sophrony and also includes valuable reflections upon the art and practice of iconography, the disposition of the iconographer, the artistic methods used by the saint and some notes on the practical realisation of the illustrated projects.

Creativity, Freedom and the Icon:

“Inspiration from on High depends to a considerable extent on us – on whether we open our heart so that the Lord – the Holy Spirit Who ‘stands at the door and knocks’ – does not have to enter forcibly…The Lord preserves the freedom of those created in His image.”[4]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

Interwoven with quotations such as the above from Saint Sophrony, the preliminary chapter contains reflections on his artistic approach, on iconographic practice and the necessary disposition of the iconographer, emphasising the inner life, humility and divine grace. Sister Gabriela writes that:

“The most direct way to form an image of God is through the heart, the meeting place between God and man, but this remains a personal and hidden form. There is a visual path to the heart, which is the way of the icon.”[5]

Describing the iconographic art as an expression of the spiritual world, she writes on the importance of humility throughout the process, saying that the iconographer:

“…seeks Divine Inspiration for his[6] work and in order to receive this, rather than some other influence, he needs a humble and prayerful attitude, recognizing that he is not the master of the situation…The iconographer will try to free himself from all that hinders or is contrary to the action of Divine inspiration. This requires both humility and asceticism, but as ascetic feats may lead to pride, and thus deter grace, it is humility that is the essential part. This keeps him both open to others and their suggestions and open to grace. It preserves a rigorous questioning and checking in prayer with his conscience and with the ideal which is the humble example of Christ…This divine humility is unattainable on earth, but in striving towards it and revealing one’s inner thoughts and states to one with greater experience in the spiritual life, a fuller understanding may be reached. The iconographer aims to humble himself, giving place for grace to act so that he becomes a servant or assistant of the icon that is created rather than its creator.”[7]

Humility is, of course, one of the most important aspects of the Christian path and its acquisition and eternal value is at the heart of the theology of both Saint Silouan the Athonite and Saint Sophrony. Saint Silouan tells us that “the Holy Spirit instructs us in the humility of Christ, that the soul may ever carry within her the Divine grace which gladdens the soul.”[8]

Another central feature in the theology and life of Saint Sophrony was his tireless search for increasing knowledge of the Creator. The ‘…search for the knowledge of God was the entire endeavour of Father Sophrony’s life and it found expression in his art.’[9] Saint Sophrony wrote of this in connection to creativity, reflecting that:

“The continual climb towards further and further knowledge of God is also a creative act, though of an especial order.”[10]

Later in his life all these subjects which had so captivated him would coalesce in his iconographic work. As described in the previous summaries, although Saint Sophrony had formerly been a professional painter in Paris, for several decades he largely abandoned painting in order to completely devote himself to the spiritual life as an Athonite monk and spiritual father. However,

“…after long years dedicated to prayer, the circumstances of Father Sophrony’s life changed and he took up painting again. Now he was able to bring the fruit of all he had learned from his spiritual experience while drawing upon the wide knowledge he had gained as a young artist. With this he embraced the great tradition of iconography.”[11]

Continuing on to describe his working approach, we are told that he,

“…drew on all his earlier artistic knowledge to express in a unique way his own rich spiritual life and monastic experience.”[12] “Every icon was imbued with prayer and each new idea was submitted to careful testing as to whether it conformed to sacred tradition. Father Sophrony embraced the iconographic tradition with all his heart, choosing it as the most suitable way of expressing the spiritual world. However this did not constrain his freedom and his creative spirit was ever awake within the framework of the icon, always keeping a personal touch.”[13]

Drawings:[14]

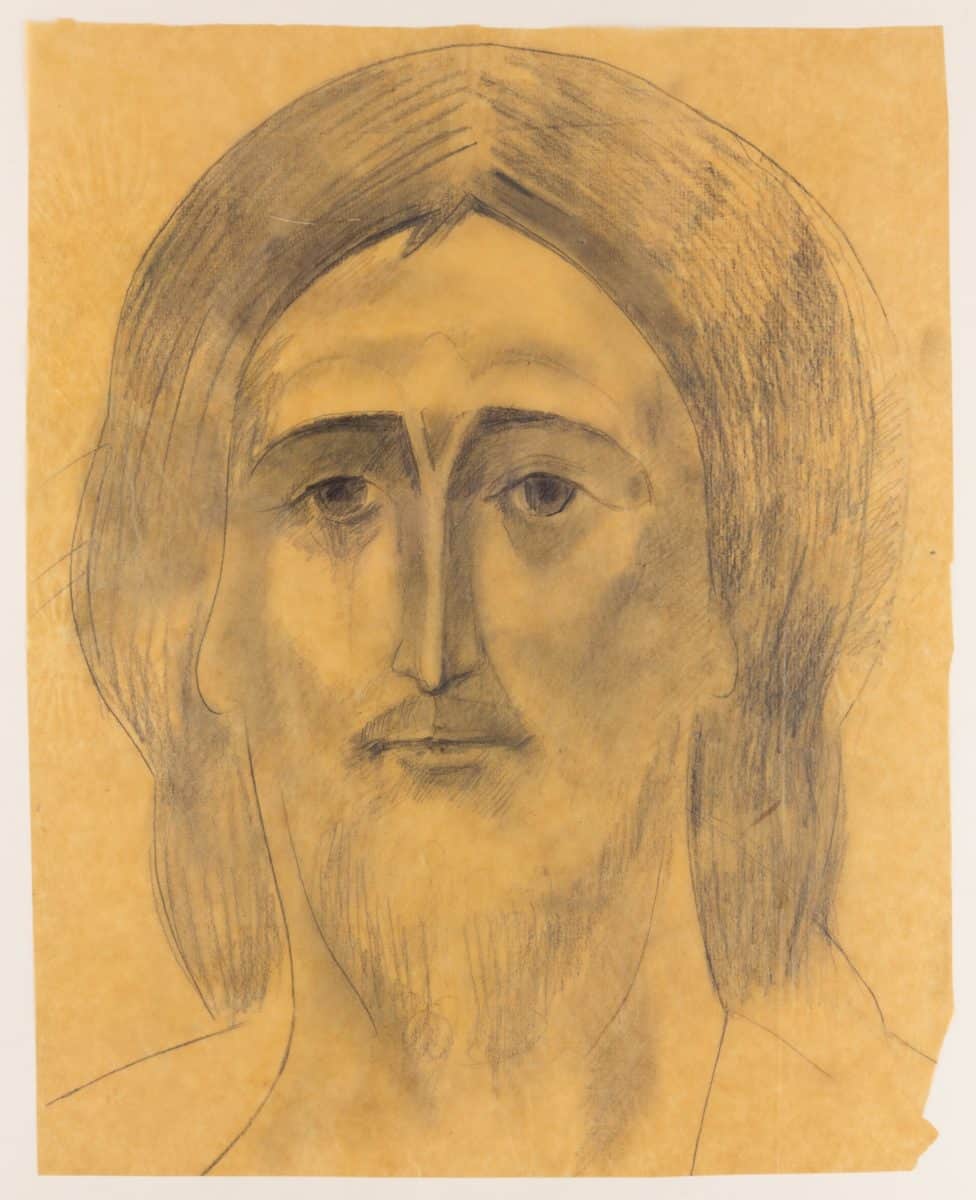

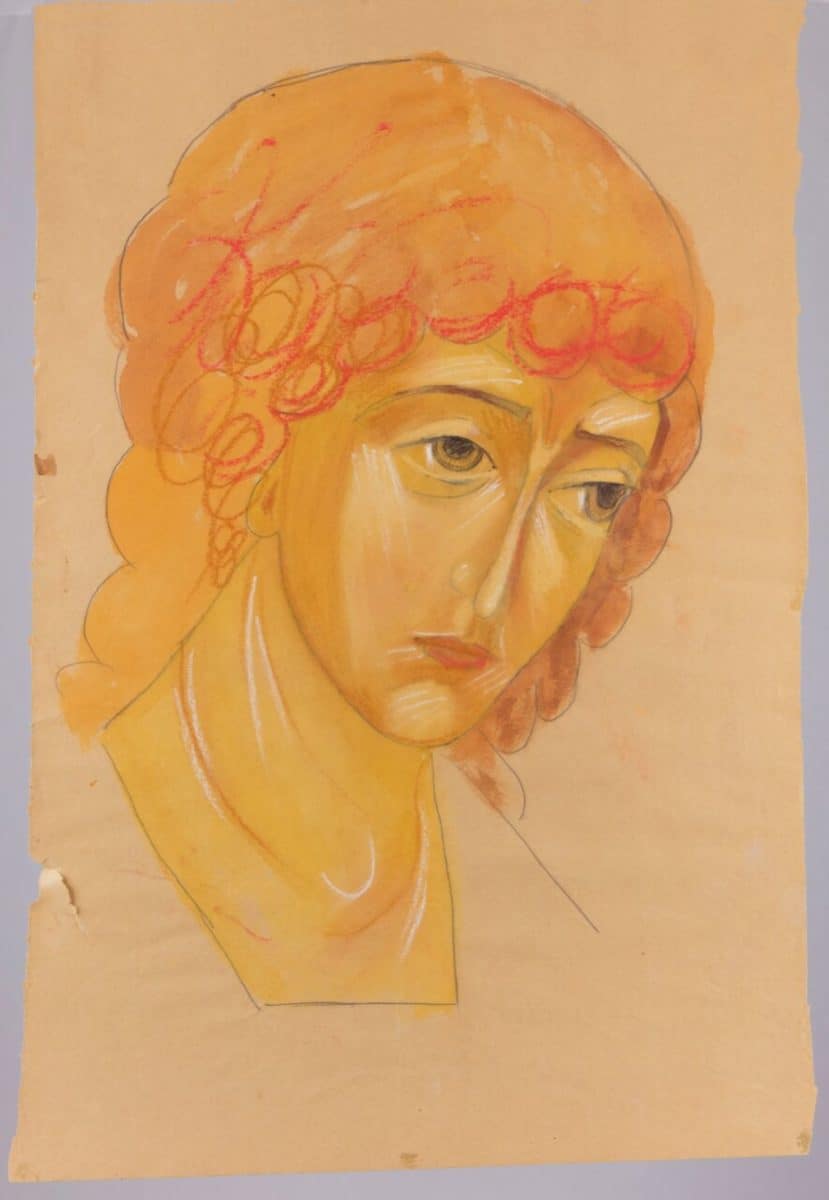

“Before commencing work on a face, Father Sophrony made several preparatory drawings, first as studies and finally as exact drawings of the facial features. Another consideration was the scale, size, and position of each figure.”[15]

The following are a small selection of Saint Sophrony’s drawings featured throughout the book. Many are ‘working drawings’, which are not intended as final works but are preliminary studies intended as part of a process of preparation towards other work such as murals or panel icons. For an iconographer this is an uncommon approach but it is a characteristic of his unique practice. The studies were used to refine and develop expressions and resemblances as well as working out how to optimally complement and harmonise with the wider compositional scheme. “Father Sophrony also made preparatory studies in soft pastel. With this method he was able to test the colouring and expression in a more palpable way than that of shaded pencil drawings.”[16]

Christ, by Saint Sophrony, pencil on discoloured greaseproof paper. Iconostasis, St Silouan’s Chapel, Community of St John the Baptist, 1988, 39 x 31.3 cm.[17] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“There is no icon of Christ that corresponds to our thoughts, expectations and dreams. When I see an icon of Christ, I just note that it IS Christ and my mind soars up immeasurably higher.”[18]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

This drawing of the Face of Christ was made in preparation for a panel icon which is in the iconostasis in St Silouan’s Chapel at the Monastery of St John the Baptist. Here, we see an example of Saint Sophrony’s continuing search to depict Christ’s image by means of art, he “…never ceased in his attempt to portray the Face of Christ more faithfully. Every time, at best only a small fragment came near to what he sought.”[19]

Angel, the ‘Father’, by Saint Sophrony, colour study in pastel and watercolour on paper. For the Holy Trinity mural, Refectory, Monastery of St John the Baptist, mid/late 70s, 55.7 x 37 cm.[20] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Searching for the right expression, Father Sophrony made this colour study using soft pastels with the addition of some watercolour, in preparation for a mural of the Holy Trinity in the monastery’s refectory.[21] The face radiates a poignant look of dispassion, combined with infinite divine love and deep compassion for His creature.

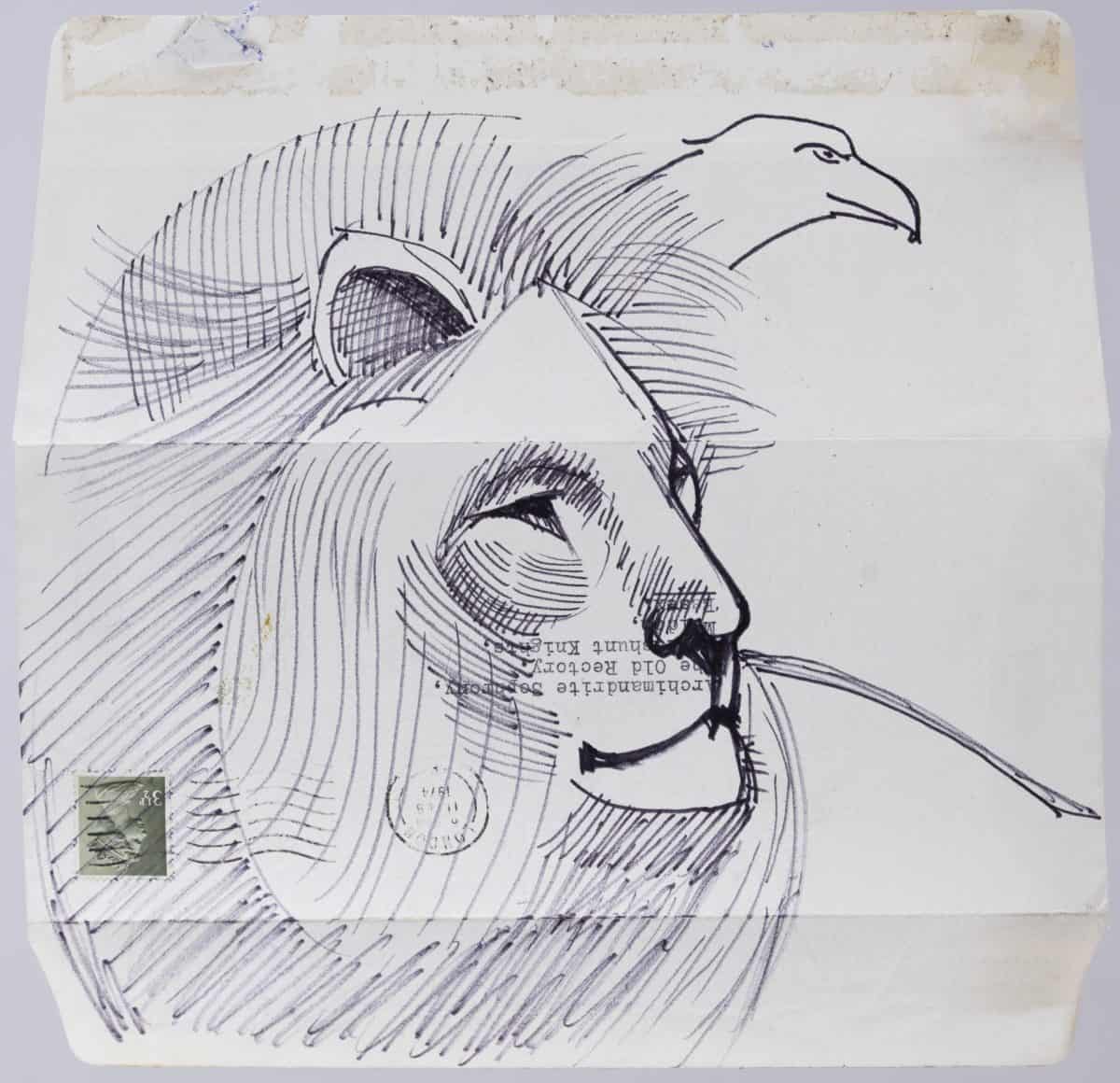

Lion, symbol of Saint Mark, by Saint Sophrony, pen on paper (envelope). Sketch for icon of Christ in Glory, 1972, 22 x 21.5cm.[22] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Saint Sophrony frequently made impromptu sketches on any available pieces of paper for the various projects underway. This study of the head of a lion for the icon of Christ in Glory is an example where an unfolded envelope addressed to Archimandrite Sophrony at the Old Rectory has been used. Note: the 3½p stamp and postal marking of 6pm 11th February 1974.

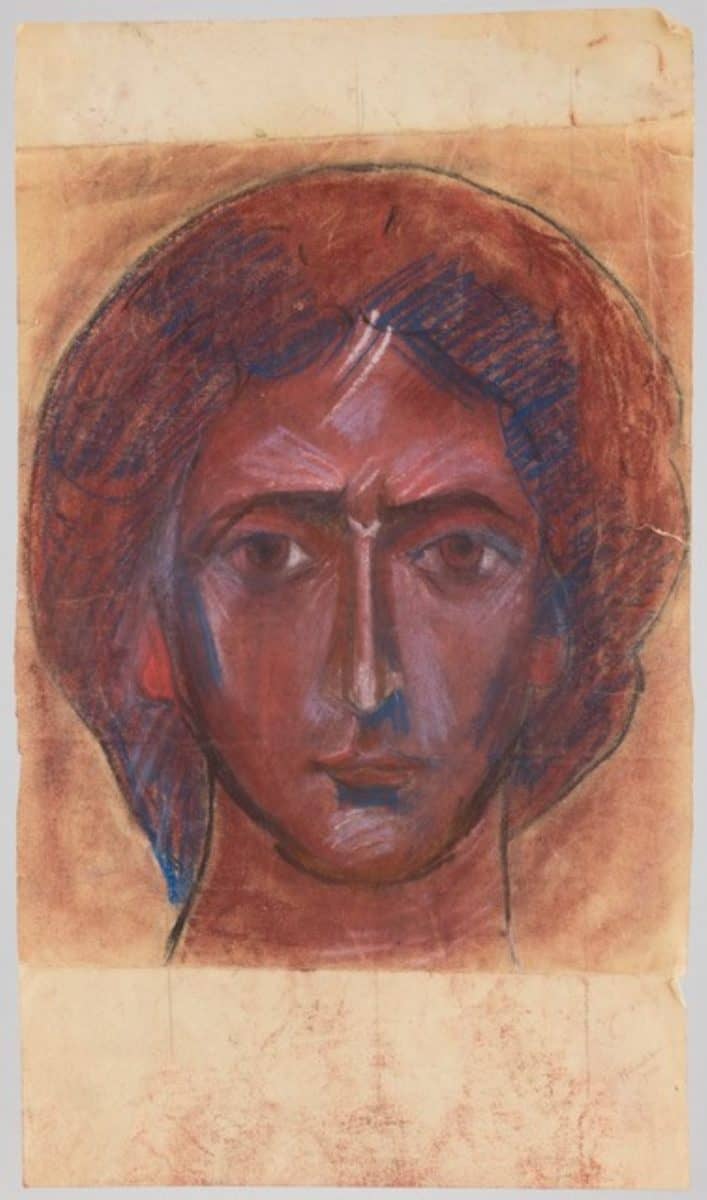

Red Seraphim Angel, by Saint Sophrony, pastel on paper. Study of face for ceiling in St Silouan’s chapel, early 1980s, 56 x 32cm.[23] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“The Seraphim can be severe, to evoke a salutary fear in the onlooker.”[24]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

This pastel study depicts the Seraph emphasising his fiery characteristics. With rich dark red undertones and diaphanous highlights in vermillion and light blue, the shadow areas in deepest blue contrast with the predominant red tones. Father Sophrony explained that the features of the Seraphim should resemble Christ’s, having been created in His image.

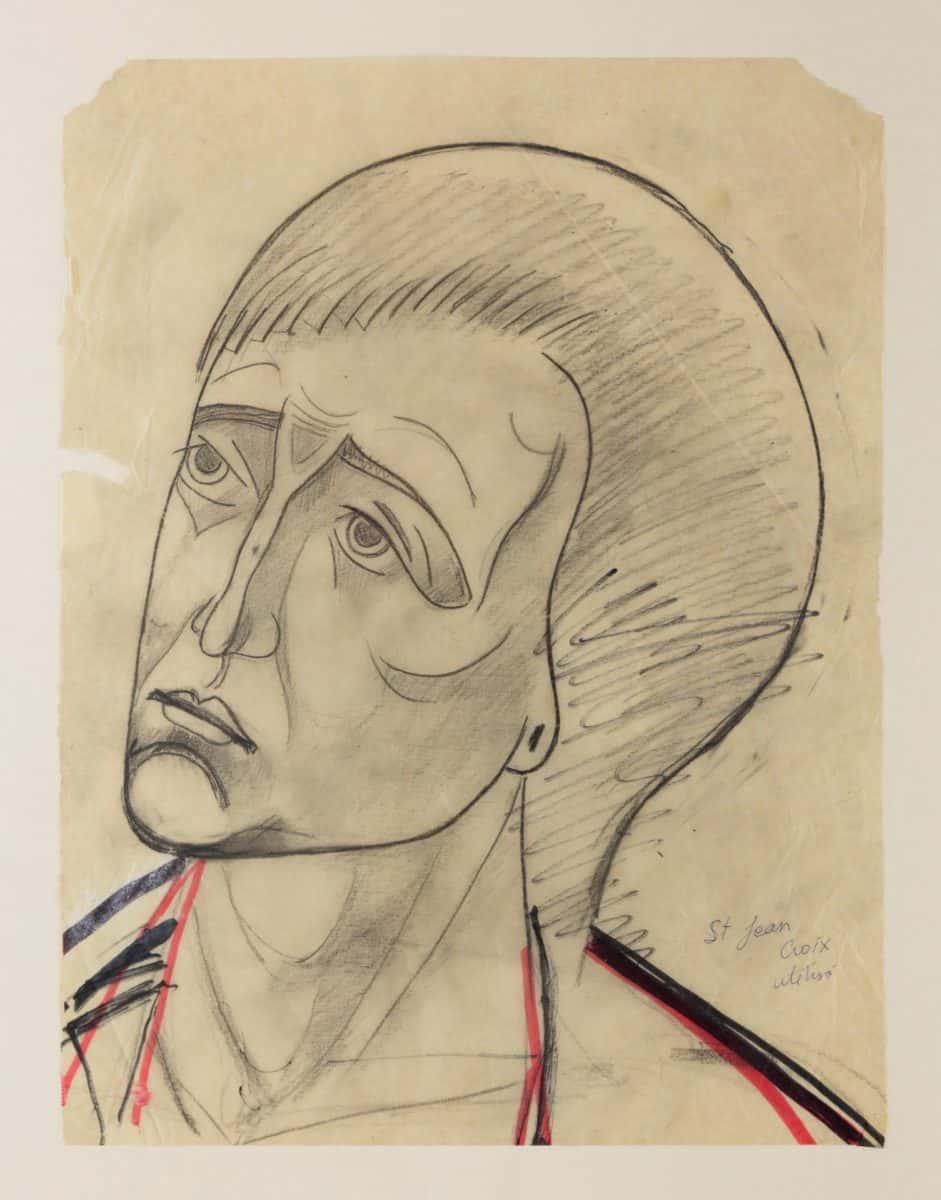

Saint John at the Cross, by Saint Sophrony, pencil and felt-tip on greaseproof paper. Drawing for the mural of The Crucifixion, St Silouan’s Chapel, early-mid 80s, 38 x 28.5cm.[25] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“When drawing the eyes, if a line is drawn across the base to close it a little, the look is intensified, more concentrated and directs the gaze further.”[26]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

This drawing of Saint John the Evangelist was based on an earlier painting made of him in the monastery’s Refectory, retaining the facial features but changing his expression. This is the moment at the Cross where he and the Mother of God flanking the Lord beheld Him with utter love, dispassion, and grief but also wonder and awe. The lines in felt-tip pen are present to indicate the exact placement of the drawing when being positioned on the wall in preparation for the image to be transferred.

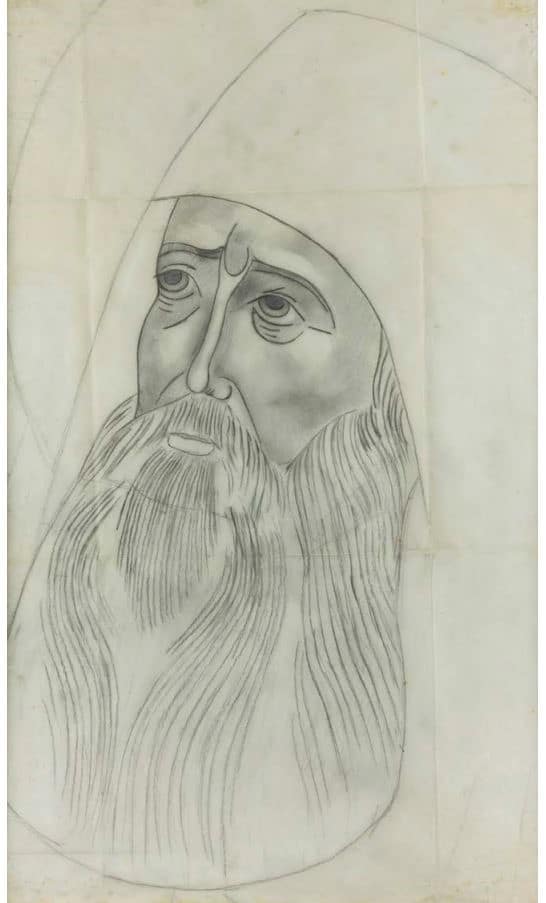

Saint Silouan the Athonite by Saint Sophrony, pencil on tracing paper. Drawing for a mural in the Refectory, mid/late 1970s, 64.5 x 39.2cm.[27] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Saint Sophrony made this drawing as a facial study based on the first icon created of Saint Silouan, which had been painted by Leonid Ouspensky in the 1950s in Paris. Saint Silouan is depicted in supplication to Christ Who, in the full image, is in the upper left corner. This drawing was used for a mural of the saint which is in the monastery’s Refectory. In the 1980s, Saint Sophrony went on to make the first frontal depiction of Saint Silouan, initially as a drawing for a mural and subsequently both these were further developed for panel icons.[28]

Murals:[29]

Two mural projects are documented in the next section, the murals of the Monastery of St John the Baptist’s Refectory, painted in mid-late 1970s and early 80s, and the murals of the monastery’s Chapel of St Silouan, which were painted in the mid 1980s. The iconographic program for the Refectory was designed in order that the room could also serve as a place of worship. However, in the early 1980s, it became possible to build another chapel at the monastery. Almost the same wall painting program was used for the chapel, yet by this time the techniques and facial expressions had significantly evolved.

Specially devised techniques were used to thinly apply oil paint directly to the gypsum plaster. Sister Gabriela explains that ‘…the nature of the walls was such that they were easily saturated, therefore only a small amount of paint could be used in order to avoid an unwanted sheen. For this reason the preparatory drawings had to be thoroughly worked out so the changes needed on the wall were kept to a minimum and a matt surface could be preserved.’[30]

A soft colouration and matt effect was favoured, as ‘the culture of the surface was of great importance to Father Sophrony, especially in the case of wall paintings. Here it was of prime importance that the surface be totally matt or non-reflective, while the painting was to be light and luminous in order to produce walls with paintings that would not impose themselves but form a suitable atmosphere and space for prayer. He reasoned that the church, where monks spent most days and nights, was their ‘living room’. As such the walls should be in harmony with the Liturgy in particular and not be disturbing or tiring for those present.’[31]

The Refectory, west view, murals in oil paint on gypsum plaster by Saint Sophrony and members of his community. Monastery of St John the Baptist, mid-late 1970s-1982.[32] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

This image shows the painted Refectory looking westwards. At the far end above the door is the mural of Saint Silouan in supplication to Christ (see earlier drawing and description), to the left is the Holy Trinity icon mural and to the right above the double doors is a Deisis mural. Seraphs embellish the ceiling. Although the work was largely completed by 1982, some final touches were made in 1991-2 under Saint Sophrony’s supervision. By this time he was in his early 90s.

Angel, the ‘Holy Spirit’, mural in oil paint on gypsum plaster by Saint Sophrony and members of his community. Detail from the mural of The Holy Trinity, the Refectory, Monastery of St John the Baptist, mid-late 1970s-1982.[33] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“Beauty is achieved when the colour is consistent over the whole face, rather than a bit of yellow or pink etc. here and there.”[34]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

The design for this mural was based on Saint Andrei Rublev’s great icon, however, a number of changes were made to the design and in order “to emphasize that only the second person of the Trinity, Christ, was Incarnate, the other two Angels were left in white, to give a more incorporeal image…Father Sophrony thought that yellow ochre was the most noble and fitting colour for faces, in this case with a minimalistic modeling on top. Here is emphasized the expression of humble love and ascent.”[35] The complete mural of the Holy Trinity icon can be seen in the earlier summary of Seeking Perfection in the World of Art.

The Empty Tomb, mural in oil paint on gypsum plaster by Saint Sophrony and members of his community. The Refectory, Monastery of St John the Baptist, mid-late 1970s-1982.[36] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

In this mural of the Empty Tomb, the lighting is intentionally softened and the face of the Angel has been painted without highlights to emphasise that the scene depicted occurred at dawn, in twilight. The myrrh-bearing women can be seen on the right with faces showing surprise and puzzlement. In the lower part of the mural one can see the concealed kitchen doorway and refectory hatch.

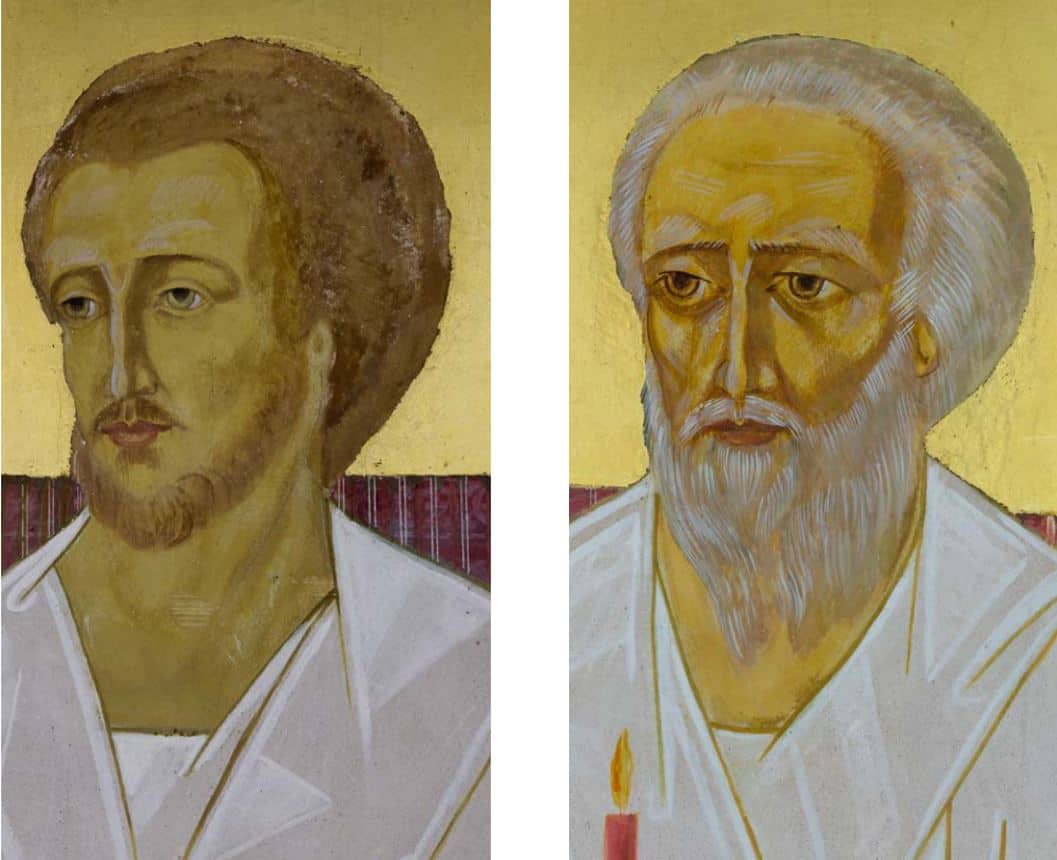

The Faces of Saint James of Alpheus and Saint Matthew at The Last Supper, by Saint Sophrony. Mural in oil paint on gypsum plaster, east wall, the Refectory, Monastery of St John the Baptist, mid-late 1970s-1982.[37] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“I would like to give expression in the eyes, in the look…”[38]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

Here are two faces of the Apostles from Father Sophrony’s first depiction of the Last Supper, on the east wall of the monastery’s Refectory. Both faces are serene and noble with penetrating eyes. As usual, the ‘culture of the surface’ was given great importance and this can be seen in the overall textural qualities and in the depiction of Saint Matthew where a technique of ‘scratching out’ sharpens and emphasises the details of his hair and beard.

The Chapel of St Silouan, east view, murals in oil paint on gypsum plaster by Saint Sophrony and members of his community. Monastery of St John the Baptist, mid 1980s.[39] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Here can be seen the murals of the Chapel of St Silouan, looking towards the iconostasis and the second rendering of the Last Supper, which is on the east wall. The ‘Deacon doors’ to the left and right of the iconostasis are adorned with embroideries of the Archangels Gabriel and Michael. On the iconostasis from right to left, are Saint Silouan, Christ the Saviour, the Mother of God and Christ Child, and Saint John the Baptist. The icon of the Mother of God and Christ Child was painted long before the construction of the chapel but as it was ideal for this location, the iconostasis and other icons were then designed and created to harmonise with it.

The head of Christ at The Last Supper, mural in oil paint on gypsum plaster by Saint Sophrony and members of his community. Monastery of St John the Baptist, east wall, mid 1980s.[40] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“We must not put many shadows on the face of Christ, He is all light.”[41]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

Here the Face of Christ radiates total dispassion and surrenderment, yet tension in the final hours leading to His Passion. Saint Sophrony described the moment, saying “He has a look of goodness, without looking at any special point (any specific direction), it is already Salvation, and it is not the struggle anymore.”[42] The wider mural depicts the moment as Judas is leaving the room, “which gave Christ the freedom to speak openly with his disciples. All attention of the apostles is directed towards Christ…”[43]

Christ with Elijah and Moses, upper part of the Transfiguration, murals in oil paint on gypsum plaster by Saint Sophrony and members of his community. Monastery of St John the Baptist, east wall, mid 1980s.[44] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“Christ in the Transfiguration is all light, almost no shadows and outlined in white, to give a luminous effect.”[45]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

The transparency and delicate colouration of the chapel murals are particularly well suited to the luminous image of the Transfiguration of our Lord with Prophets Moses and Elijah. The scene is highly atmospheric and clearly conveys the divine and Uncreated Light of the transfigured Lord. This timeless and ascetic rendering which focuses on absolute essentials is characteristic of Saint Sophrony’s iconography.

Row of Ascetics, murals in oil paint on gypsum plaster by Saint Sophrony and members of his community. Monastery of St John the Baptist, west balcony wall, mid 1980s.[46] From left to right the ascetics are: Saints Nilus, Macarius, Sisoes, Anthony, Silouan, Poemen, Arsenius, Paisius, Seraphim. Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

The Row of Ascetics adorns the choir balcony at the west end of the Church, and the saints chosen were those of similar ascetic experience to that of Saint Silouan, who is situated at the centre of the group. To create an aesthetic harmony all the saints in the row were drawn proportionately to each other using an identical grid, with the exception of Saint Seraphim of Sarov. Regarding the mural of Saint Silouan (see close-up image in the earlier summary of Seeking Perfection in the World of Art) Sister Gabriela explains that it “…was originally painted before Saint Silouan was glorified. The halo was added and the inscription of his name changed in 1988…As this was the first time Father Sophrony had painted his elder in full face, he used the techniques he had acquired as a portrait painter. Later when painting the icon for the iconostasis, he used a stricter stylised form…”[47] The muted and earthy colouration evokes the extreme humility of the ascetical path.

Panel icons:[48]

“One has to know the technique but also the art. A good icon is like a painting. Like a prayer written with beautiful letters. With such an icon one can live all one’s life and just by looking at it one changes.”[49]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

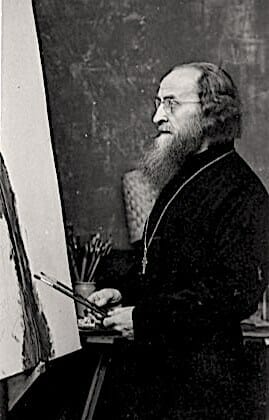

Saint Sophrony painting in the early 1960s.[50] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

Regarding his approach to painting panel icons, Sister Gabriela explains that,

“…when Father Sophrony started painting icons, he studied the art of egg tempera painting and used this technique…The icons therefore were painted in the traditional manner using earth pigments starting with the darker tones and finishing with the lighter ones on top, producing the effect of light coming from within. Often on large icons, strong undercoats of solid colours were preferred beneath the top shade. This helped to create a vivid presence of the saint or subject painted. The Russian ‘floating’ style was used when colours were painted on panels in a flat position. In this case, both the thicker tones and glazes in a very diluted state were applied or ‘floated’. However, when an important work had to be finished, Father Sophrony preferred to use oils since he was most familiar with this medium…This allowed him to use thin transparent glazes which blended and united with the lower layers of the varnished egg tempera…Finally the whole icon would receive another layer of olifa to keep a united and continuous surface, preferably resembling porcelain or ivory.”[51]

As with his contemporaries Father Gregory Kroug and Leonid Ouspensky, Saint Sophrony preferred a creative approach, reflecting his previous artistic background and experience as a painter as well as his sharp aesthetic and spiritual perception.

Saint Panteleimon, panel icon in egg tempera on gesso by Saint Sophrony. 56.5 x the 53.3cm, icon for iconostasis, Saint John’s Chapel, Monastery of St John the Baptist, 60s/70s.[52] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“Icons can be painted as a craft, and this is good, one can pray in front of these, but icons can also be art, and it is this quality that we should strive after.”[53]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

This icon of Saint Panteleimon is one of several icons which was painted by Saint Sophrony for St John’s Chapel, the first chapel created at the monastery in 1959. The chapel’s iconostasis had been painted by Father Gregory Kroug for their previous chapel in Paris but was dismantled and brought with the embryonic community from there to England. The Saint Panteleimon icon was made as one of a set of interchangeable icons for a space on the north side of the iconostasis. The colours are brilliant and jewel-like, the gaze penetrating, and his face shows determination, purity, firmness and strength.

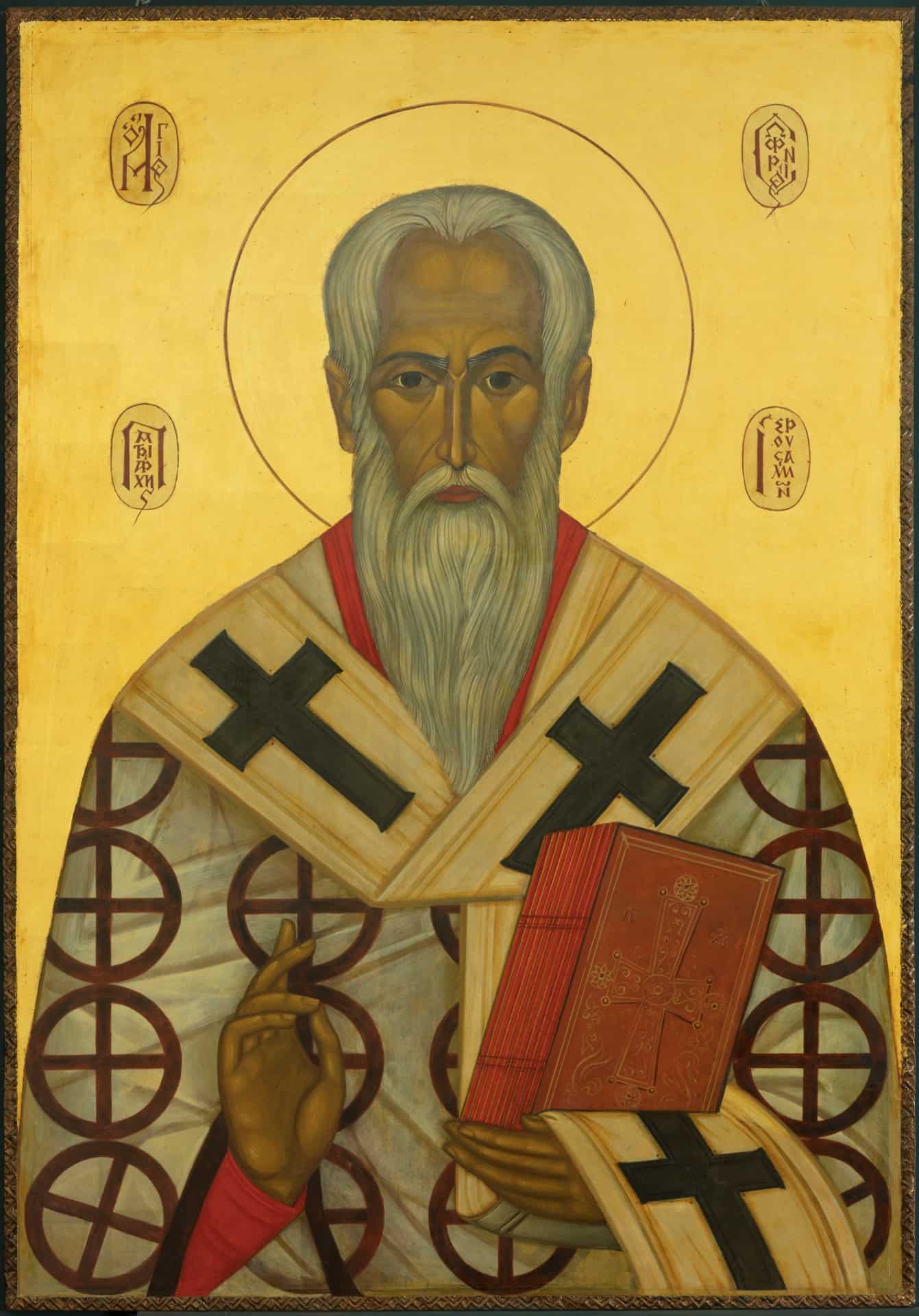

Saint Sophrony of Jerusalem, panel icon in egg tempera on gesso by Saint Sophrony. 106.7 x 74.5cm, Monastery of St John the Baptist, 60s/70s.[54] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

This large icon of Saint Sophrony’s patron saint, Sophronios Patriarch of Jerusalem, is particularly remarkable. The surface qualities are exceptionally fine, and the paintwork has a porcelain and luminous quality. The facial expression conveys great depth and subtlety and was the subject of much consideration. Sister Gabriela explains that “this icon took Father Sophrony several years to complete in the search to find the appropriate expression for his patron saint: an eagle-like, all-seeing look, fitting for a bishop and a pastor of the church.”[55]

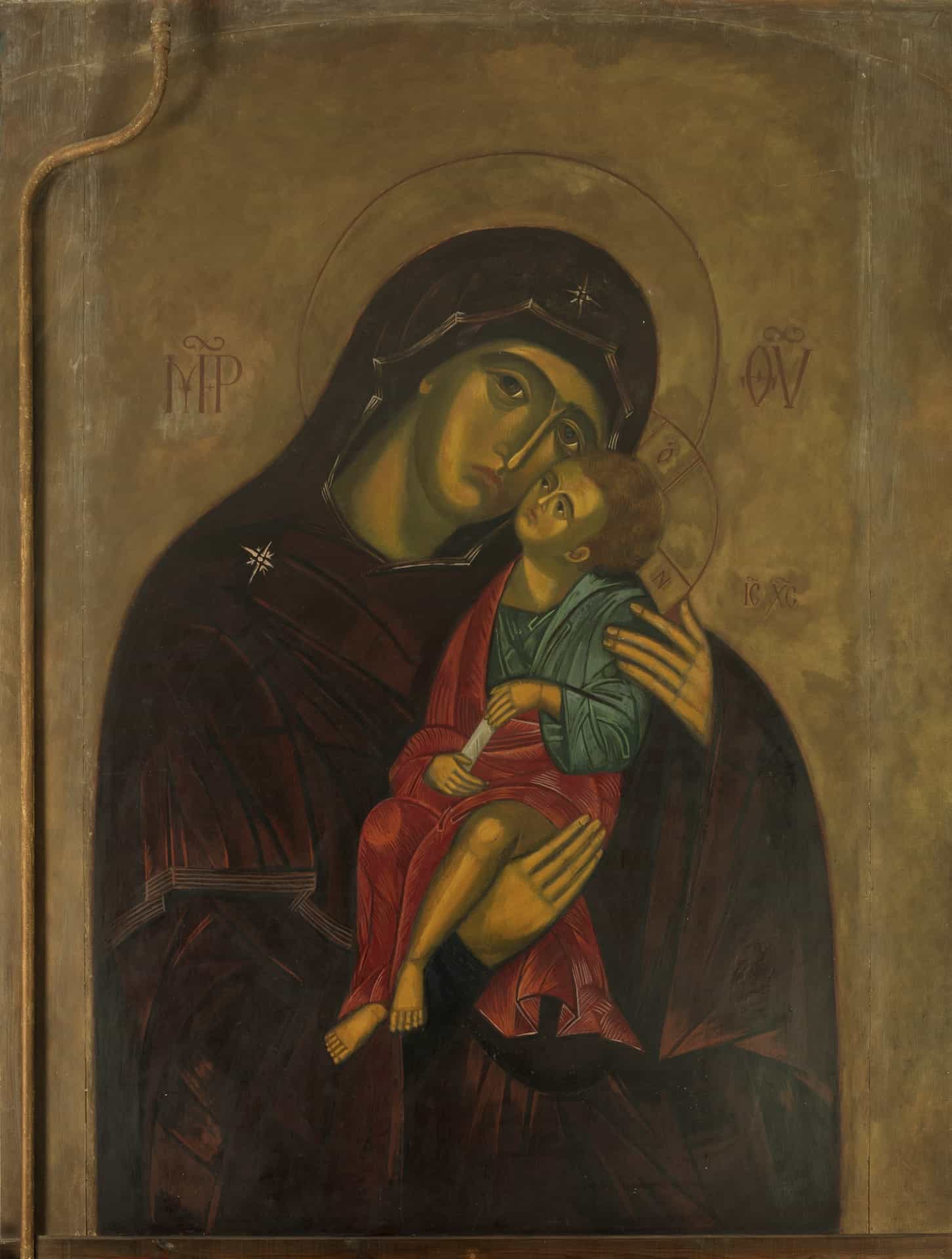

Mother of God, mural icon in egg tempera on gesso by Saint Sophrony. 190 x 155cm, Monastery of St John the Baptist, early 1960s.[56] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“In the icon of the Mother of God I have tried to express her spiritual beauty. When one looks at her, one is drawn to her and in no way repelled. She is strict, but also there is a great gentleness.”[57]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

This icon was painted for the ample chimney breast in the study of the Old Rectory, with a calculated distortion in order to be seen from the desk opposite. The photograph above was taken from this slightly oblique angle and thus looks as it was intended to be seen. The intense gazes of the figures and subtle, muted colouration emphasise the sober monastic quality of the icon.

Design:[58]

The final section of the book highlights a range of Saint Sophrony’s design projects. He had a great interest in and gave meticulous attention to every aspect of the design process, carefully planning each and “every detail, not only of icons and murals, but also of lettering, wrought iron work, embroideries, and patterns. In all cases, the detail had to fit with the whole.”[59]

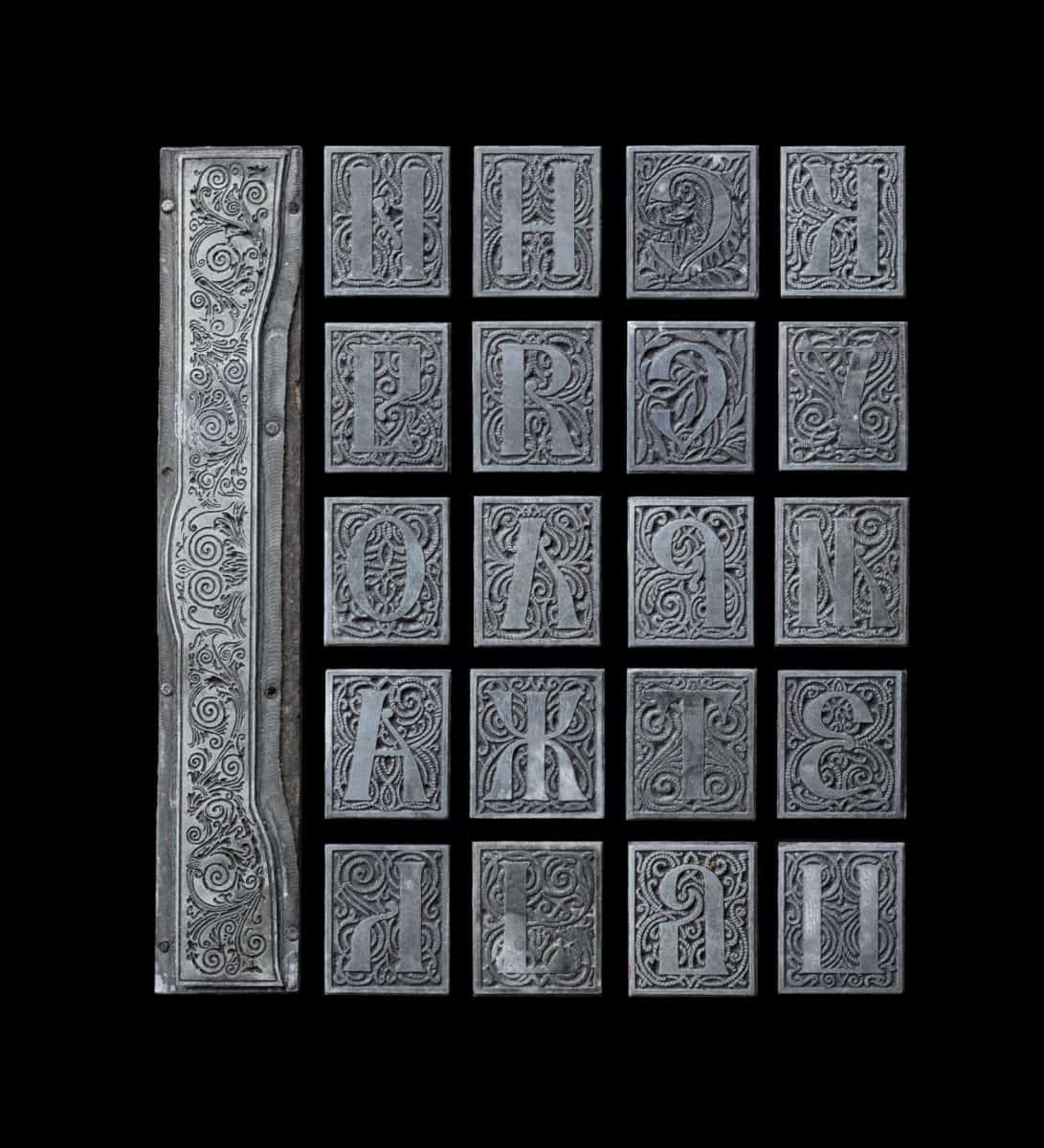

Metal type letter blocks and decorative elements, etched metal, by Saint Sophrony. Single letters 2.1 x 1.7cm, wider letters 2.2 x 1.7cm, all 2.3cm high, decorative frieze 2.8 x 16.3cm, 2.3cm high, Paris, 1952.[60] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

“To draw a beautiful letter is difficult, it requires much work.”[61]

Saint Sophrony the Athonite

Saint Sophrony created these letter blocks whilst compiling the text and arranging the layout and printing for his book Staretz Silouan in Paris in 1952. This was the first Russian edition of the book. He also created sections of decorative pattern, one of which can be seen on the left of the photograph. He designed and probably carved or etched the letter blocks himself, creating letters and ornament which are richly detailed and harmonious, yet sober.

Saint Sophrony had temporarily left Mount Athos for the purpose of printing the words of his beloved elder, as Paris had the necessary equipment and infrastructure for such a task. However, as a result of the intensity of the work and his years of strictest asceticism, especially throughout the war, he became gravely ill and required major surgery which left him as a convalescent for some years and unable to return to the Holy Mountain. Gradually disciples gathered around the holy elder and this eventually led to a desire for their own monastery. The divine providence of the Lord meant that the monastery was to be founded in Essex, England, where they moved in 1959. It was in this new location that Saint Sophrony’s artistic work began to flourish anew.

Carpet for Royal Doors, woollen tapestry, by Saint Sophrony and members of his community. 214 x 106cm, St John’s Chapel, Monastery of St John the Baptist, mid 1970s.[62] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

On arrival at the new monastery in 1959 the first major task was to create a chapel in the Old Rectory dedicated to Saint John the Baptist. This tiny gem of a chapel was created with much care, and attention was given to every detail. Above is the carpet designed by Saint Sophrony for the chapel’s Royal Doors. It has a dynamic design which points towards the Holy Table in the altar area and “illustrates the meeting point that takes place at the Royal Doors.”[63]

It was embroidered by members of his monastic community using wools of light jade green, yellow ochre and cerulean on beige. Subsequently he designed several other carpets, including one in the Chapel of St Silouan, which was also embroidered by community members.

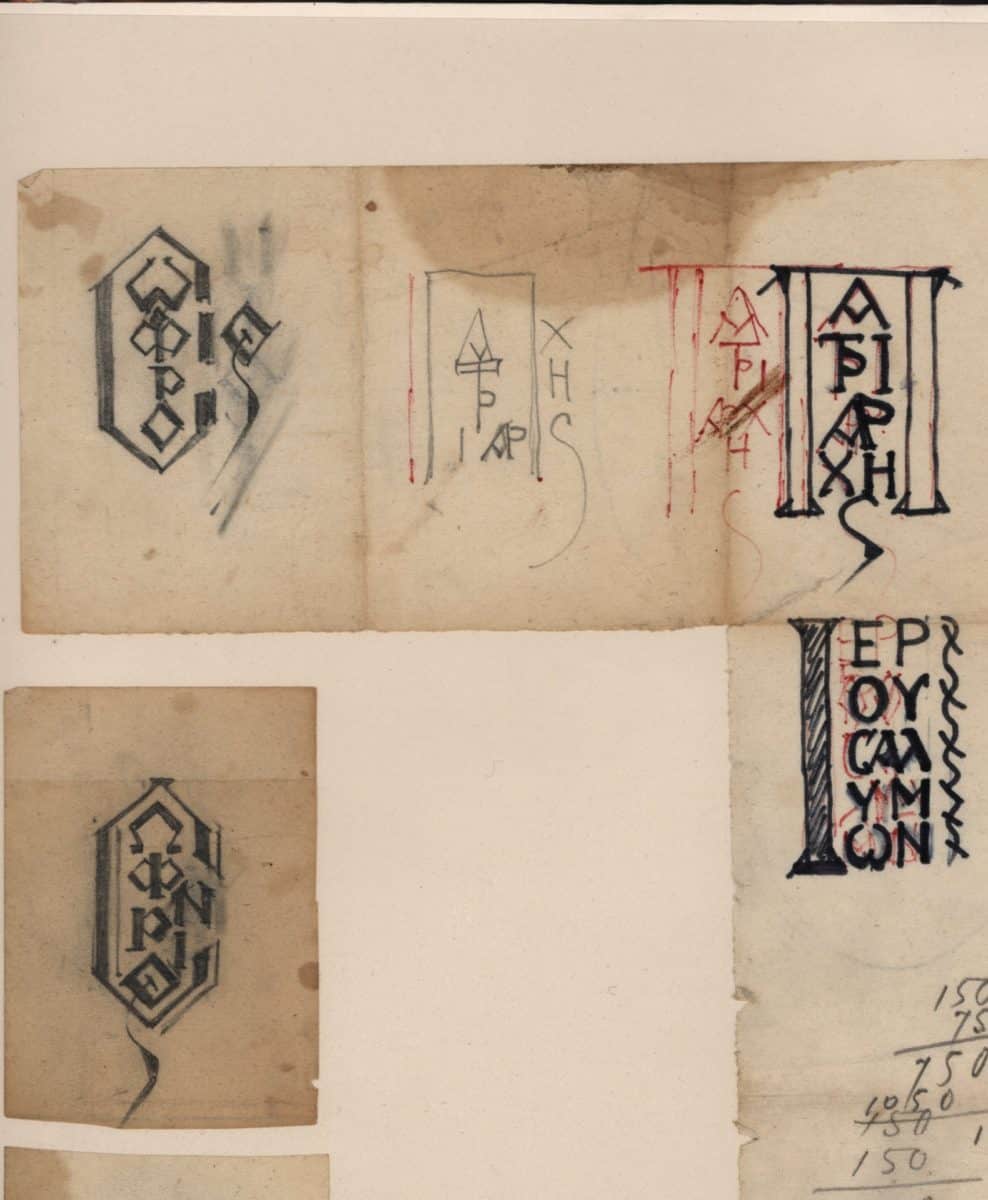

Sketched lettering designs for the Saint Sophronios of Jerusalem icon, pencil and pen on paper, by Saint Sophrony. 7.6 x 6.3cm (average), Monastery of St John the Baptist, early 1960s.[64] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

The above example shows Saint Sophrony’s approach to letter design for his icons, in this case that of Saint Sophrony Patriarch of Jerusalem. Dedicating much time to the composition, layout and stylisation of the lettering, he said that “the inscription should be just about legible, requiring some effort to read so that it may be remembered, unlike advertisements which one reads unconsciously, automatically.”[65] Here potential design configurations for each word – Sophronios, Patriarch, Jerusalem – are being tested.

Stavropegic Cross, emblem of the Monastery, wrought iron, designed by Saint Sophrony. 98cm high, drive of the Monastery, The Old Rectory, Tolleshunt Knights, 1969.[66] Image: ©The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

In 1969 Saint Sophrony designed the Stavropegic cross, the monastery’s emblem. Sister Gabriela writes that “this cross, symbol of the Monastery, was designed by Father Sophrony and crafted by an artist blacksmith near Manassia Monastery in Serbia. It represents Christ, the cross, standing on the earth, the globe, with its foot resting on the location of Jerusalem. This is to symbolise Christ having conquered the world, both material, the globe, and that which is immaterial, the spiritual, represented by spheres and upturned arches round the globe.”[67]

*************

Painting as Prayer, The Art of A. Sophrony Sakharov, by Sister Gabriela, first edition. The Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex, 2017. Hardcover, pp. 192, colour plates: 159, black & white plates: 8, ISBN-13: 978-1909649125.

It has also been translated into Russian and Romanian.

There is a full Catalogue Raisonée in two volumes cataloguing the full body of the Saint’s artistic work.

The books can be purchased on Amazon or directly from The Patriarchal Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, The Old Rectory, Tolleshunt Knights, By Maldon, Essex CM9 8EZ, UK. Please write to Sister Magdalen.

This review is for the hardback edition, however, a paperback version is also available through Amazon.

Footnotes:

[1] Detail from The Resurrection, mural by Saint Sophrony, Sr Gabriela, Painting as Prayer, p. 116.

[2] Sr Gabriela, Painting as Prayer, p. 188.

[3] There is also a smaller paperback edition available online, but this review concerns the hardback edition.

[4] Archim. Sophrony, We Shall See Him, 1988, p. 120, Sr Gabriela, Painting as Prayer, p. 13.

[5] Sr Gabriela, Painting as Prayer, p. 11.

[6] For the sake of simplicity Sr Gabriela uses the male form.

[7] Sr Gabriela, Painting as Prayer, p. 13.

[8] Archim. Sophrony, Saint Silouan the Athonite, p. 161, Sr Gabriela, Painting as Prayer, p. 191.

[9] Sr Gabriela, Painting as Prayer, p. 11.

[10] Archim. Sophrony, Wisdom from Mount Athos, Crestwood: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1974, p. 13. Painting as Prayer, p. 14.

[11] Sr Gabriela, Painting as Prayer, p. 15.

[12] Ibid. p. 9.

[13] Ibid. p. 15.

[14] Ibid. pp. 18–75.

[15] Ibid. p. 181.

[16] Ibid. p. 182.

[17] Ibid. p. 25.

[18] Ibid. p. 185, Saint Sophrony, from the author’s notes.

[19] Ibid. p. 185.

[20] Ibid. p. 26.

[21] Ibid. pp. 80 to 83, for photograph of the full mural.

[22] Ibid. p. 33

[23] Ibid. p. 37.

[24] Ibid. p. 186.

[25] Ibid. p.48.

[26] Ibid. p. 186.

[27] Ibid. p. 61.

[28] For photographs of the drawing, mural and the icon of Saint Silouan (which are in St Silouan’s Chapel) please refer to my earlier review of Seeking Perfection in the World of Art.

[29] Sr Gabriela, Painting as Prayer, p. 76 and p. 130.

[30] Ibid. p. 185.

[31] Ibid. p. 181.

[32] Ibid. pp. 78-9.

[33] Ibid. p. 83.

[34] Ibid. p. 188.

[35] Ibid. p. 188.

[36] Ibid. pp.90-1.

[37] Ibid. pp.99.

[38] Ibid. p. 188.

[39] Ibid. pp. 102-3.

[40] Ibid. p. 105.

[41] Ibid. p. 188.

[42] Ibid. p. 189.

[43] Ibid. p. 188.

[44] Ibid. pp. 112-3.

[45] Ibid. p. 189.

[46] Ibid. pp. 126-7.

[47] Ibid. p. 190.

[48] Ibid. pp. 130–51.

[49] Ibid. p. 17, quotation from Saint Sophrony.

[50] Ibid. p. 6

[51] Ibid. p. 179-80.

[52] Ibid. p. 132.

[53] Ibid. p. 7, quotation from Saint Sophrony.

[54] Ibid. p. 140-1.

[55] Ibid. p. 190.

[56] Ibid. p. 146.

[57] Ibid. p. 190.

[58] Ibid. pp. 152–75.

[59] Ibid. p. 153.

[60] Ibid. p. 162.

[61] Ibid. p. 191.

[62] Ibid. p. 172.

[63] Ibid. p. 191.

[64] Ibid. p. 159.

[65] Ibid. p. 191, quotation from Saint Sophrony.

[66] Ibid. p. 170.

[67] Ibid. p. 191.

His icons have a unique calmness to them.

Thank you very much for your comment. This calmness was also a characteristic of Saint Sophrony himself, as is described beautifully in Seeking Perfection where it is written that “Father Sophrony had a generally ‘elegant’ way of being, of behaving and manner of working. All was done with a calm and careful, prayerful, attentiveness. Nothing was executed in haste or haphazardly. This trait was apparent in all aspects of his life.’

Thank you for making this known!

I wonder why they all look numb, i’ve read on the descriptions they are meant to be expressive but i don’t see it, im thinking, if the faces were more expressive the viewer would mirror them and feel the emotions that are written in the descriptions.

I wonder why is that?

Thank you very much for your comment, which touches on an important matter. The holy figures have moved beyond transient emotional states, which belong to the fallen world, and have attained to the impassivity of the eternal Kingdom. They radiate complete sanctification and surrenderment to the will of God. St Sophrony had a profound understanding of this having spent many years totally immersed in prayer, repentance and spiritual mourning. He knew such states from personal experience and also witnessed them in his many encounters with holy persons. The emphasis on the virtue of dispassion is one of the special characteristics which distinguishes St Sophrony’s iconography. Where there is an emphasis on emotions, what we see is a psychological not a spiritual art. If implemented in the context of the icon this would result in a fall away from iconographic expression towards sentimentality and humanism.