Similar Posts

“Man is the measure of everything.” That, at its core (in nuce), is every humanism…Therefore, all humanisms, all hominisms are, in the final analysis, idolatrous and polytheistic in origin…all the European humanisms strive consciously or subconsciously, but they strive unceasingly, for one result: to replace faith in the God-man with a belief in man, to replace the Gospel of the God-man with a gospel according to man, to replace the philosophy of the God-man with philosophy according to man, to replace the culture of the God-man with a culture according to man…

-St. Justin Popovich, Reflections on the Infallibility of European Man

Marcel Duchamp playing chess in 1952. Photo by Kay Bell Reynal, in the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art

As Dr. Larry Shiner put is, “art is not just an “idea” but is, instead, a system of ideals, practices, and institutions…”[1] all of which arise from a worldview. If the worldview changes, then naturally, the art will change as well. With the loss of an integrated culture arising from tradition there emerges a shift of worldview: a culture based on individualism and rationalism. Hence a parallel may be seen between the ever changing and fragmentary modern art theories, and Protestantism’s ever multiplying theologies. As mentioned in the first part of this article, the worldview of a civilization is known by its fruits- its art.[2] So what “fruits” have I looked at recently?

The other day, out of curiosity, I picked up an art magazine while shopping at the art store, the one that seemed the most alluring and unusual, the most creative and playful. Creative in that it broke the standard mold of the stuffy art publication I had become accustomed to years ago in graduate school. Actually, the magazine reminded me of the resurgent interest in painting, expressive figuration and pastiche of the 80s, which was a reaction against the Conceptual and Minimal Art of the previous decades.[3] There was a time when painting led the way: it had a kind of preeminence. Now it’s just another option in the plethora of possibilities. There are many reasons for this, but some might say that Duchamp should at least be partly blamed.

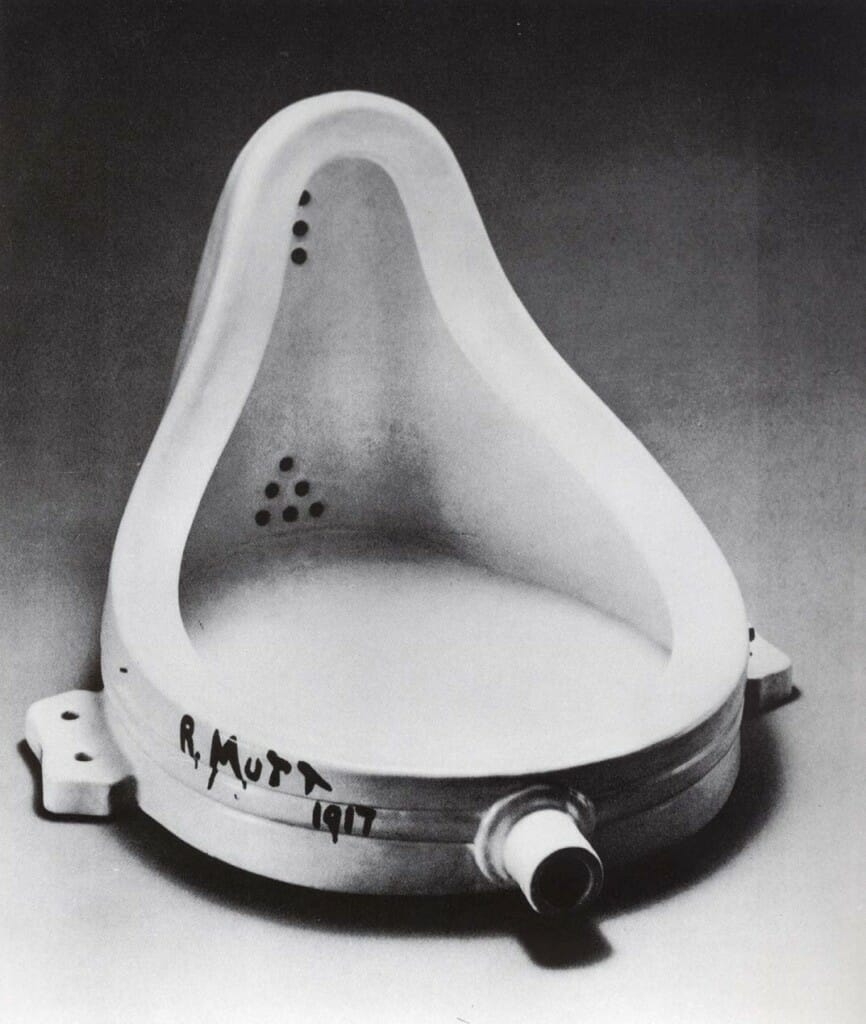

Fountain, Marcel Duchamp, 1917.

This urinal, signed under the pseudonym R.Mutt, was submitted to an open exhibition but rejected, without a doubt to Duchamp’s delight.

It has ever since become one of the most famous, and to some infamous, of Duchamp’s “Readymades.” It would come to play a major role in the development of Conceptualism.

In a short essay , published in The Blind Man, NY, 1917, Duchamp says , ” Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under a new title and point of view-created a new thought for that object.”

Duchamp opened up a can of worms with his urinal that ever since hasn’t stopped leaking, with “consequences that have culminated in the dilemmas of postmodern art.”[4] The urinal, titled “Fountain,” is one of the most famous of his “readymades,” the ordinary manufactured objects he would turn into works of art by minimally altering, re-contextualizing or signing them. These challenged the accepted views of the unique work of art, authorship, originality, hand-made craftsmanship, beauty, creativity, art as commodity, etc. Further, his work ironically and irreverently questions the powers of legitimation in the art world: the role of the critic, dealers, market, museum, buying public and gallery.[5] Consequently “retinal art,” art that was mainly visual, received a hard blow and painting took the back seat.[6] As Duchamp would say, “I wanted to get away from the physical aspect of painting…I was interested in ideas- not merely visual products…This is the direction in which art should turn: to an intellectual expression…”[7]

Duchamp’s “painting at the service of the mind” was a rejection to what he called “animal expression” and “the more sensual appeal of painting.”[8] Art was no longer to be considered bound to the constraints of physical objects, since these easily fall prey to popular taste and the mechanisms of legitimation. Gradually Conceptualism, or art as idea, which amounts to a kind of rationalism, would take center stage. The artist was to reign supreme in his infallibility to call anything art, in defiance to whatever constrained his freedom, or rather, his self-assertion.[9] His task now was to question the nature of art. Hence in 1969 the conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth, in his essay, Art after Philosophy, remarks, “The ‘value’ of particular artists after Duchamp can be weighed according to how much they questioned the nature of art.”[10]

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs, 1965.

Kosuth would develop further the ideas of Duchamp and become one of the leading representatives of Conceptualism by the late 60s and 70s.

In this work we see him taking the idea of the “readymade” in another direction, treating it as a philosophical inquiry into ontology, semantics and the nature of representation.

It would appear as if the Conceptualist emphasis on the “mind,” its turn from “appearance” to “concept,” would in fact serve to lead art back to its metaphysical import and spiritual function, more in accord with the traditional doctrine. But, in fact, it can be said that herein we find an intellectualism that dualistically opposes matter, in the spirit of the Cartesian dictum, “I think therefore I am.”[11] Hence, Conceptualism, in disdaining the retinal, aesthetic and physical components, radically undermines art’s function as an incarnational receptacle of spiritual realities- its sacramental potential. Unlike most of early Modernism, it relegated the “spiritual” to the margins, considering it mere romanticism. Hence, some thought, the more soulless, lacking in feeling, mechanical, minimal, and intellectually cold things became, the better. So the “ideas” of Conceptualism are not to be confused with the realm of ideas (forms or archetypes) of Plato; nor are they the logoi ofpatristic Tradition; neither is the concern for things “serving the mind” anything pertaining to things noetic. These things would presuppose the Divine, the Sacred, matters outside the scope of most Conceptualists.

Sol Le Witt, Color Grids, 1975. Suite of 45 color etchings, 20 x 20 in. / 50.8 x 50.8 cm. each. Edition of 10.

In Le Witt we find the convergence of Conceptualism and Minimalism. The utter simplicity of his work betrays an attempt to “ameliorate matter.” In his essay “Paragraphs on Conceptualism,” published by Artforum in 1967, he notes, “Anything that calls attention to and interests the viewer in…physicality is a deterrent to our understanding of the idea…The conceptual artist would want to ameliorate this emphasis on materiality as much as possible or to use it in a paradoxical way (to convert it into an idea).”

It goes without saying that I do not agree with Duchamp’s extreme relativism, the premise that a work of art is a work of art just because the artist calls it so. Neither do I applaud his nihilism, in which we see how he sympathizes with the anti-conformist and anti-art tactics of the Dada movement.[12] Yet, perhaps Duchamp’s cynicism serves as a salutary reassessment to the notions of “art” we take for granted as norm and have institutionalized. In many ways this institution of art runs counter to the traditional doctrine of art as discussed earlier. So, ironically, he is not just a villain. In fact, it could be said that his critique calls us, from an Orthodox perspective, to pause and reconsider what we mean when we speak of ‘traditional art.” He shakes us up out of our stupor and comfort zone, reminding to ask ourselves about our “system of values” or “system of ideals” – our worldview.

Jörg Immendorff, Cafe Deutschland, 1984. Oil on Canvas, 285 x 330 cm.

This work by Immendorf is a good example of the Neo-Expressionism coming out of Germany in the 80s.

In it we can clearly see the painterly defiance at the time against Conceptualism. Rather than “feelingless” intellectualism, here we have the psyche unrestrained, let loose, unloading a cacophony of imagery unto the canvas. Although predominantly abstract in overall effect, the painting is actually made up of a pastiche of figurative elements.

In any case, happily, I thought, this magazine seemed to unashamedly embrace painting and drawing from a variety of angles: playful image making, stirred by masterful skill. Perhaps most magazines representing the “serious” contemporary art discourse would consider it an oddity, a misfit in the crowd, irrelevant to the intellectually “pressing issues.” In this publication aesthetic pleasure took the front seat over vapid conceptualism. Regardless, in the end, for all of its alluring visuals, the magazine lacked depth, had no redemptive value. It induced a momentary aesthetic euphoria, but it left you with a bad aftertaste. What started as a playful dream actually began to betray a darker undertone.

Mimmo Paladino, Ronda Notturna, 1982. Oil on canvas, 300 x 400 cm.

Paladino is one of the Transavarguardia painters of the 80s, an Italian movement that also resisted Conceptualism and paralleled the Neo-Expressionism of the US and Germany. In his work he combines figuration, abstraction, personal symbolism, mythology and primitivism in an attempt to suggest mystery and revive the emotive power of painting.

The magazine can be seen as an image of “art” as we know it today, an alluring spectacle, a very seductive one, a labyrinth of ideas, theories, streaming out of the unrestrained psyche. And in the labyrinth, door after door, you can open, enter and enjoy. It doesn’t really matter whether you have a rationalist bent, or a proclivity for aesthetic hedonism, in the end it all amounts to the same thing- extremes meet. It promises liberty, playfulness, joy, aesthetic pleasure, intense feeling, and even icy intellectual gratification. But, does this Wonder Land of simulacra deliver its promises? Can we find our way out from its twisting passageways? Is there to be found an intimation of the Sacred?

Be that as it may, we can go on all day speaking of this malaise. That’s not my point here. However, the magazine is just one example, a reminder of our blind spots concerning the contemporary philosophy of art, which most take for granted as, “how things have always been,” or as the “most developed understanding,” of art. But, in fact, it is a very recent development and for that matter a kind of anomaly in human civilization, a shift of paradigm or worldview. Perhaps this blind spot is due to the fact that we tend to buy into the notion of so called “progress” without even realizing it. Therefore, we might think, “Things always change for the better, the past is irrelevant, the present, the ‘spirit of the times’ determines the state of things. We know better now than our primitive forebears.” And this amounts to a kind of derision of Tradition.

But, as noted before, Tradition is not to be confused with institutional conservatism, formalism, fundamentalist legalism, social customs, or a naïve nostalgia for the good-old-past. Believe me, I’m not interested in advocating a return to Byzantine times, or hoping to see once again knights decked out in shiny armor. The point is that Tradition is not to be considered subject to historical determinism. Rather, it can be described as “that continuum of knowledge which deals with the meaning and purpose of man’s life, and the possibility of his rebirth. It is a knowledge ever new, fresh, immortal, always present, not subject to time, which is the basis of all the great civilizations.”[13] If the “progressive” anti-traditional sentiment is felt anywhere it could be said that it is felt the strongest in our attitudes towards art, although in other respects we consider ourselves to be “traditional” Orthodox.

Under the spell of this historicist mentality we sink into a kind of amnesia about how art was understood universally in world civilizations for millennia before the Renaissance. Dr. Larry Shiner tells us in The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, “The modern system of art is not an essence or a fate but something we have made. Art as we have generally understood it is a European invention barely two hundred years old.”[14] In other words, Dr. Shiner places the invention of the notion of “fine art” as a consequence of the social transformations that unfolded in the 18th century.Hence, it could be said that our contemporary presuppositions about art ultimately begin to be planted in the Renaissance, bud in the 18th century, and finally bloom in the early 20th century, with the fragmentary avant-garde movements of Modernism. In short, our views about “art” arise from the abandonment of a religious consciousness in culture and the embrace of a secular mentality. Man replaced God and the museum replaced the Cathedral.

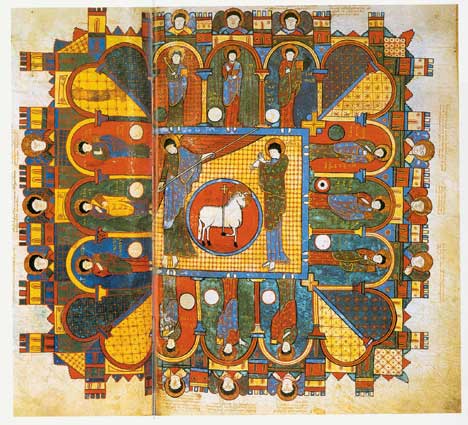

It’s good to remember, as we have already shown, that the notion of “art” as a subjective statement, in pursuit of novelty, having no functional value, in other words, “art for art sake,” is nothing but an anomaly of recent world history. It betrays our fragmented, unintegrated civilization that values individualism over community, appearances over truth, opinion over revelation, and the contingent over timeless first principles. It’s a notion that forgets the traditional doctrine of art, that is, the universal understanding of art as techne, a manufacturing skill, a fitly joining together, meant to supply for both the needs of the body and soul. Yes, and in supplying for the soul it embodied the Sacred. In this understanding symbolic and functional values converge and aid man in his union with God. As Aristotle put it once, “the general end of art is the good of man.”[15] But unfortunately most of us don’t know what the Good is. Nevertheless, for all major civilizations from time immemorial, art has always had the religious function of mediating and manifesting divinity. It served as vehicle for the coming together of the heavenly and earthly realms. In short, for the traditional man art is incarnational, looking forward to the Incarnation.

For traditional man art is done according to a heavenly pattern, “And look that thou make them after their pattern, which was showed thee in the mount.” (Exodus 25:40) His cities, temples, habitations, armors and tools, were fashioned according to revealed archetypes. Hence, “The member of a tribal or traditional society may be called homo religiosus (“religious man”) precisely because he perceives both a transcendent model (or archetype) and a mundane reality that is capable of being a model to correspond to the transcendent model. Furthermore, he experiences the transcendent model as holy, that is, as manifesting absolute power and value. In fact, it is the sacred quality of the archetype that compels him to orient his life around it. Finally, the sacred is recognized as such because it appears to man within the profane setting of everyday events. This is the hyerophany (“appearance of the sacred”), that is, when the supernatural makes itself felt in all its numinosity in contrast to the natural order.”[16]

As to the relationship of craftsmanship to the archetype, in traditional societies, Annanda K. Coomaraswamy has noted, “For all the arts, without exception, are representations or likenesses of a model; which does not mean that they are such as to tell us what the model looks like, which would be impossible seeing that the forms of traditional art are typically imitative of invisible things, which have no looks, but that they are adequate analogies as to be able to remind us, i.e., put us in mind again, of their archetypes.”[17] For traditional man the Heavens gave order to the polity, Jerusalem was a type of the Heavenly City. Therefore, art without the Sacred is cut in half, blunted. Art, without the Sacred as its first principle, becomes solipsistic, a skill without purpose or meaning, it gradually becomes an irrational luxury, that is, solely relegated to what pleases our lower appetites, or merely sophistry, rather than for the purpose of nourishing man’s highest faculty and innermost aspect of the heart –the nous. How can there be art without the Divine Craftsman ordering, guiding its activity, and imparting the illumination of the Holy Spirit?

Deity Helios, embossed stone panel. Syria, 2nd Century.

In this work we see a prefiguartion in Paganism of Christ,”The Sun of Rightousness” and “Light of Life.”

This work looks forward to the Incarnation and is meant to functions as an embodiment of the Sacred. Hence, the “iconic” qualities of this stone relief are clearly evident.

Notice the halo, a symbolic feature which will become indispensable in the future development of Christian iconography.

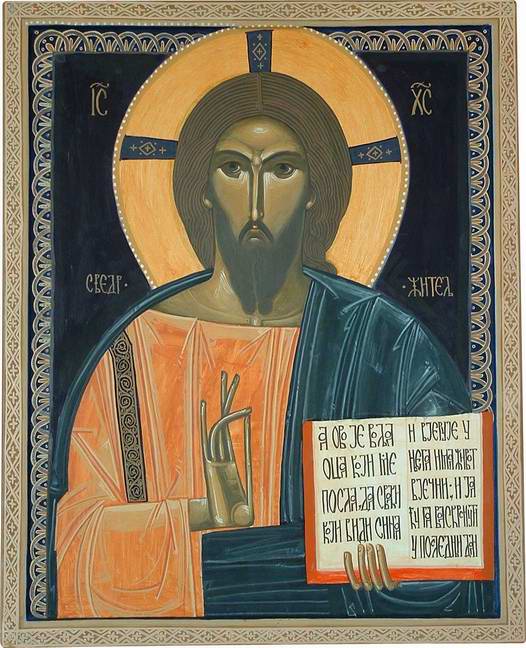

The traditional doctrine of art as expressed in past civilizations might be dismissed as an anachronism only to our detriment. No, we are not calling to a return to medieval times or a caricatured “primitive” civilization of the noble savage. In fact, Homo religiosus is still here. Whether we want to admit it or not we are all religious to our core and will always be. There will always be the “primitive” in us. Further, Tradition, as we mentioned, is “ever new, fresh, immortal, always present” and ever renewing those who partake of its waters. We can partake of these waters in the Church and thereby renew our understanding of art. Those engaging in secular art have the icon as a model to follow in reorienting their art towards the Sacred. What for ancient man could only remain in the realm of things “impossible to be seen” actually became visible in the incarnate Logos, the Divine Archetype.[18] The icon now depicts the circumscribable form of the Person of the uncircumscribed One, the Son- the Image of the Father. What was an intimation in past civilizations, a type and shadow of things to come, becomes fulfilled in the complete work of art of Church cult, which in word, image and action, depicts through symbolic realism the Mystery of the Incarnation.

To be continued…

————————————————————————————–

Notes:

[1] Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 2001, p.8.

[2]In speaking of art as a distinguishing “fruit” arising from the worldview of a given civilization, Philip Sherrard says, “What is it that distinguishes cultures that retain a grasp on life which we appear to have lost? Is there some element present in what we acknowledge to be the great civilizations of the world which is not present, or at least not cogently present, in our own latter-day civilization, if we can still call it that? If we are to judge from the art of these civilizations we are bound to say that there is…It is an art, that is to say, dedicated to the expression or revelation of realities that are more than human or natural, realities that we denote by the word “spiritual.” It is an art which presupposes that there is a realm of what we may call spiritual archetypes, or of eternal harmony, that constitutes the underlying structure of the natural physical world, and that is the source of the life and activity on which this world depends.” Philip Sherrard, Christianity: Lineaments of a Sacred Tradition, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1998, p. 2.

[3]The “transvarguardia” and Neo-Expressionist painters come to mind: Sandro Chia, Enzo Cucchi, Francesco Clemente, George Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Rainer Fetting, Jorg Immendorff, Keith Haring, etc; the “postmodernist” paintings of David-Salle and Philip Taffe can also be included here. But we should bear in mind that the painterly tendencies of the 80s, although mostly running counter to the dominance of Conceptualism, do not entirely lack a conceptual side. Of Neo-Expressionism the art critic Donald Kuspit says, “But the Neo-Expressionists claimed to be making conceptual painting — painting that was at once intellectual and empathic without being fixated on one at the expense of the other and without reifying either — suggesting they were determined to heal the split between feeling and thinking. (The German Neo-Expressionists have convincingly done so.) In contrast, the Neo-Conceptualists maintained an attitude of ironic indifference to feeling — a seemingly intellectual detachment from and skepticism about it — however much their ostensible feelinglessness is itself an expression of feeling. Indeed, their emotional nihilism — their militant eradication of all sensuous-affective expressive traces from their work — is inseparable from the feeling of self-defeat and self-loss. In contrast, the Neo-Expressionists tried to retrieve, repair, and recapitulate, in an excruciatingly personal, experiential way, the feelings of self-defeat and self-loss — the sense of the meaninglessness of the self (implicit in the idea of the split between feeling and thinking, that is, the self-division which announces the impending disintegration of the self) — endemic to modern society and epidemic in postmodern society.” Donald Kuspit, A Critical History of 20th Century Art, Chapter 9: Aspirational Esthetics and Empathic Painting: The Search for Authenticity and the Rebellion against Conceptual Pseudo-Art: The Ninth Decade. For the rest of the chapter see:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit8-9-06.asp?print=1

[4] Richard Appignanesi and Chris Garratt, Introducing Postmodernism, Totem Books, NY, 1995, p.35.

[5]“…How did a difficult and unpopular avant-garde modern art become accepted as the institutional standard of taste? Whose taste is that? The taste of the art galleries, museums, dealers and their art-buying public. In short, the merchants of art and its collectors.” Ibid., pp. 50-51.

[6]This attack on “retinal art” was taken up by Conceptualism of the 70s as a resistance to the prevailing formalist art criticism of the 60s, represented by Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried. These two critics considered the one of a kind art object, realized by the artist solely based on visual criteria, as the core defining concept of modernism. For Greenberg this also meant that the inherent properties of each artistic medium were to be maintained, without blurring definitions that would cause their collapse into one another. There was no room for aesthetic hybridity, so to speak. By the late 60s this was challenged in favor of a less restrictive, more pluralistic and “post-modern” approach, in the writings of artists such as, Allan Kaprow, Dick Higgins, Henry Flynt, Mel Bochner, Robert Smithson and Joseph Kosuth. Greenberg dismissed their tendencies as “novelty art,” lamenting the results and retaliated saying, “The different mediums are exploding…when everybody is a revolutionary the revolution is over.” See the section, “The concept and the theory of art,” in One and Three Chairs: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_and_Three_Chairs. For the Greenberg’s quotation see: Clement: Avant Garde Attitudes, 1968. The Jon Power Lecture in Contemporary Art, 17 Mai 1968. First published in: In Memory of John Joseph Wardell Power. Power Institute of Fine Arts, University of Sydney, 1969. Republished in: Greenberg, Clement: The Collected Essays and Criticism. volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957-1969. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1993, p. 292, 299.

[7] From a 1946 interview with James Johnson Sweeney in “Eleven Europeans in America,” Bulletin of the Museum of ModernArt, NY, XIII N0. 4-5, 1946, 19-21. See the reprinted version in Hersschel B Chipp, Theories of Modern Art, University of Chicago Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, 1968, pp.392-95.

[8]Ibid., p. 395.

[9]See note 11 below.

[10] Joseph Kosuth, Art after Philosophy, 1969. See: http://www.ubu.com/papers/kosuth_philosophy.html

[11]“It is possible to trace, through those three crises of modern Europe which we still call the Renaissance, The Reformation, and the Age of Enlightenment, this movement of a mind which has broken with a reality of spiritual or metaphysical order and has more and more asserted its own self-sufficiency…By the time of Descartes, this process is complete. The human mind is said to be quite capable of formulating a valid type of knowledge not only without reference to divine knowledge, but also without reference to the sensible world and its phenomena. The human mind becomes the self-sufficient arbiter of knowledge. Finally the human mind itself, as part of this downward movement, increasingly takes its clue, not from the ideas that have their source in the universal Logos, but from dicta invented by whatever philosopher or group of philosophers happens to hold the stage, dicta that become ever more mechanical and banal as the human mind disowns its divine inheritance.” Sherrard, 1998, Ibid., pp. 9-10.

[12]Of Dada he would say, “It is a sort of nihilism to which I am still very sympathetic. It was a way to get out of a state of mind- to avoid being influenced by one’s immediate environment, or by the past: to get away from clichés- to get free.” Chipp, Ibid., p. 394.

[13] Cecil Collins, Why does Art today Lack Inspiration? In Every Man An Artist, Readings in the Traditional Philosophy of Art, ed. Brian Keeble, World Wisdom, Inc., Bloomington, IN, 2005, p. 203.

[14]Shiner, Ibid., p. 3.

[15] As quoted by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, “Is Art a Superstition or a way of Life,” in The Essential Coomaraswamy, World Wisdom, Inc., Bloomington, Indiana, 2004, p. 170.

[16]Beverly Moon, “Archetypes”, in The Encyclopedia of Religion, Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1995, NY, p. 380.

[17]Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, “Why Exhibit Works of Art,” in The Essential Coomaraswamy, World Wisdom, Inc., Bloomington, Indiana, 2004, p.113.

[18] About Christ as the Archetype, St. Nicholas Cabasilas says, “It was for the new man that human nature was created at the beginning, and for him mind and desire were prepared. Our reason we have received in order that we may know Christ, our desire in order that we may carry Him in us, since He Himself is the Archetype for those who are created. It was not the old Adam who was the model for the new, but the new Adam for the old…the Saviour first and alone showed to us the true man, who is perfect on account of both character and life and in all other respects as well…We must, then, regard Christ as the Archetype and the former Adam as derived from Him.” St. Nicholas Cabasilas, The Life in Christ, SVS Press, Crestwood, NY, 1974, pp. 190-91.

Great Article, Fr. Silouan! Thank you for the insights!!!

The author of the icon, you publishe, should be written as “m i trovich.

With regards,

Philip

… so what was the mystery art magazine …

[…] On the Gift of Art: Clashing Worldviews – Orthodox Arts Journal […]

It is interesting to see the difference between Duchamp and Kosuth. One can agree or disagree whether or not a thing deserves to be knocked down but one must reserve a certain amount of reverence for the person wielding the wrecking ball. So Duchamp’s Urinal and his other ready-mades have the strength of the assassin’s bloodied knife. But Kosuth, like Lewitt and so much contemporary art is just pedantic and boring. Kosuth is like the librarian of conceptual art, so easy to “shelf” in his “radical rejection of art” with his nice clinical and documented experiences on language. …Duchamp without an edge or Magritte without any brilliance. I love Greenberg’s quote you mention: “when everybody is a revolutionary the revolution is over”. Who thought I would ever agree with Greenberg?

Come on boys it’s a big world out there if you are not finding beauty you are not looking for it !!! It’s all starting to sound like a club of self serving nay sayers and irrisponsibly dismissive.

Weilding these tired dull old axes against modernism; is that Orthodoxy’s answer to contemporary issues, hope not!

Hello John, good to hear from you!You know how it is… The challenge continues, as the Lord says, be “In this world but not of this world.” A tension that will always be present and felt the most acutely, I’m sure, by those Orthodox Christians involved in the arts. If there was not some degree of appreciation for modern art there would have been no discussion of it at all. But its limitations must be stated without hesitation, although we can if we look , as you say, find the positive. In most cases we can always find something “positive”, but what about the “fueling agent” that makes the machine tick, the main presuppositions that lead the artist to this and not that decisions, and has given us what some call “the end of art”? It would be naive to simply jump into the ban wagon of contemporary art practice just because that’s the way thing are now, without asking ourselves how our Faith factors into the picture. Yes, Beauty is ever present and fills all things, even when we disregard it, as it has been in most cases in contemporary art. And how can it not be reflected in the work of man created in the image and likeness of Beauty? It’s a matter of degrees and focus. Anyhow, remember, the article is not over…