Similar Posts

Introduction to the Project

I have been commissioned to design and paint the wall iconography for the parish church of St. John of the Ladder in Greenville, South Carolina. This beautiful temple is of Andrew Gould’s design. His OAJ article about it appears here. I intend to post updates on the iconography project occasionally.

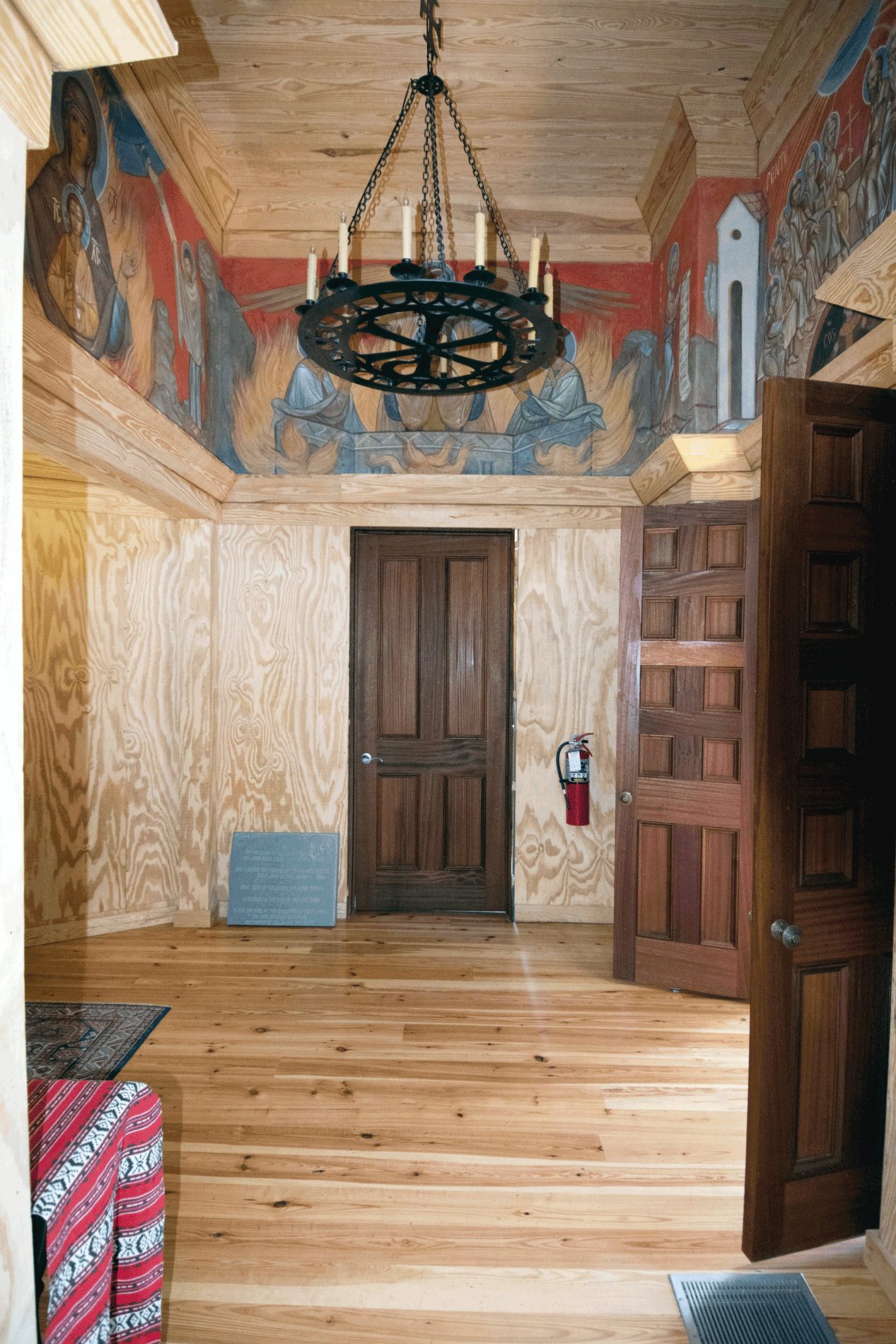

As is usual in an Orthodox church, there are vestibules to either side of the sanctuary, north and south. The room to north is traditionally the Prothesis, where the service of proskomide takes place. The room to the south has a more fluid range of uses. The Greenville parish has decided to make it a side-chapel, where smaller weekday services may take place. I completed the murals for these two vestibules first, giving time for the program of iconography in the main body of the church to develop.

The Side-Chapel of the Burning Bush

View into the side-chapel from the sanctuary. The frescoes, occupying a plaster frieze, are complete, but the lower walls, currently just plywood substrate, are still awaiting their yellow-pine paneling.

The side-chapel’s dedication to the burning bush is appropriate at St John of the Ladder. Saint John was a famous 6thcentury abbott of St Catherine’s monastery on Mount Sinai, the mountain where Moses’ encounter took place. Historians debate the location of the biblical Mount Sinai. But based on the traditional identification, Christians established a church on this mountain by the 4th century.

This church, and later in the sixth century, a monastery, was built on the site known as the location of the burning bush. Monks have lived there ever since, and the bush itself still grows there. The monastery’s original dedication was to Mary the Mother of God. From early times the Church Fathers and Mothers have exegetically linked Mary with the burning bush. In his Life of Moses, St Gregory of Nyssa writes, “The light of divinity which through birth shone from her into human life did not consume the burning bush, even as the flower of her virginity was not withered by giving birth.” 1

The bush at St Catherine’s monastery traditionally identified as the burning bush of Exodus. (Note the fire extinguisher – perhaps a note of monastic humor?)

The chapel feast is September 4, which commemorates the prophet Moses and the Burning Bush icon of the Theotokos. This icon depicts our theology of Mary with relation to scriptural fire imagery. In scripture, fire often accompanies divine encounters. Especially fire which burns but does not consume. This theme guides our iconographic program for the chapel.

The East Wall

The congregation faces the east during services. This mural is located directly above the altar table.

In the center of the east wall, the Mother of God is wrapped in flame, with the Christ child in her bosom. She is the Burning Bush itself, as we sing at vespers: “O Moses, blessed Prophet of the Lord, you beheld the immaculate and all-holy Virgin in the bush that you saw swaddled in divine fire, but remaining unconsumed…”

To her right, Moses is removing his sandal, having heard the divine command: “Do not come near; put off your shoes from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5). Moses gazes at the Hebrew letters “YHWH.” This is the divine name “I AM,” which God revealed to Moses at the burning bush. The inscription in Christ’s halo is the Greek translation of this name.

On the left, Moses reaches to receive the tablets of the law. This event in Exodus also took place on Mount Sinai. On the tablets, the Hebrew numbers one through ten indicate the Ten Commandments. The hand of God extends from an orb representing the divine darkness into which Moses cannot see. This sequence of scenes originates from the rich iconographic tradition of St. Catherine’s monastery on Mount Sinai.

In our chapel, this imagery is directly above the altar, which gives it a particular liturgical meaning. This is the classic image of God revealing himself to man. With her arms in the “orans” position of prayer, the Theotokos’ form resembles a chalice, in which Christ takes flesh and blood. Our hymns frequently relate the Eucharist to fire, as in the prayer before Communion: “Rejoicing and trembling at once, I partake of Fire, I that am grass. And, strange wonder! I am bedewed without being consumed, as the bush of old burned without being consumed.”

The North and South Walls

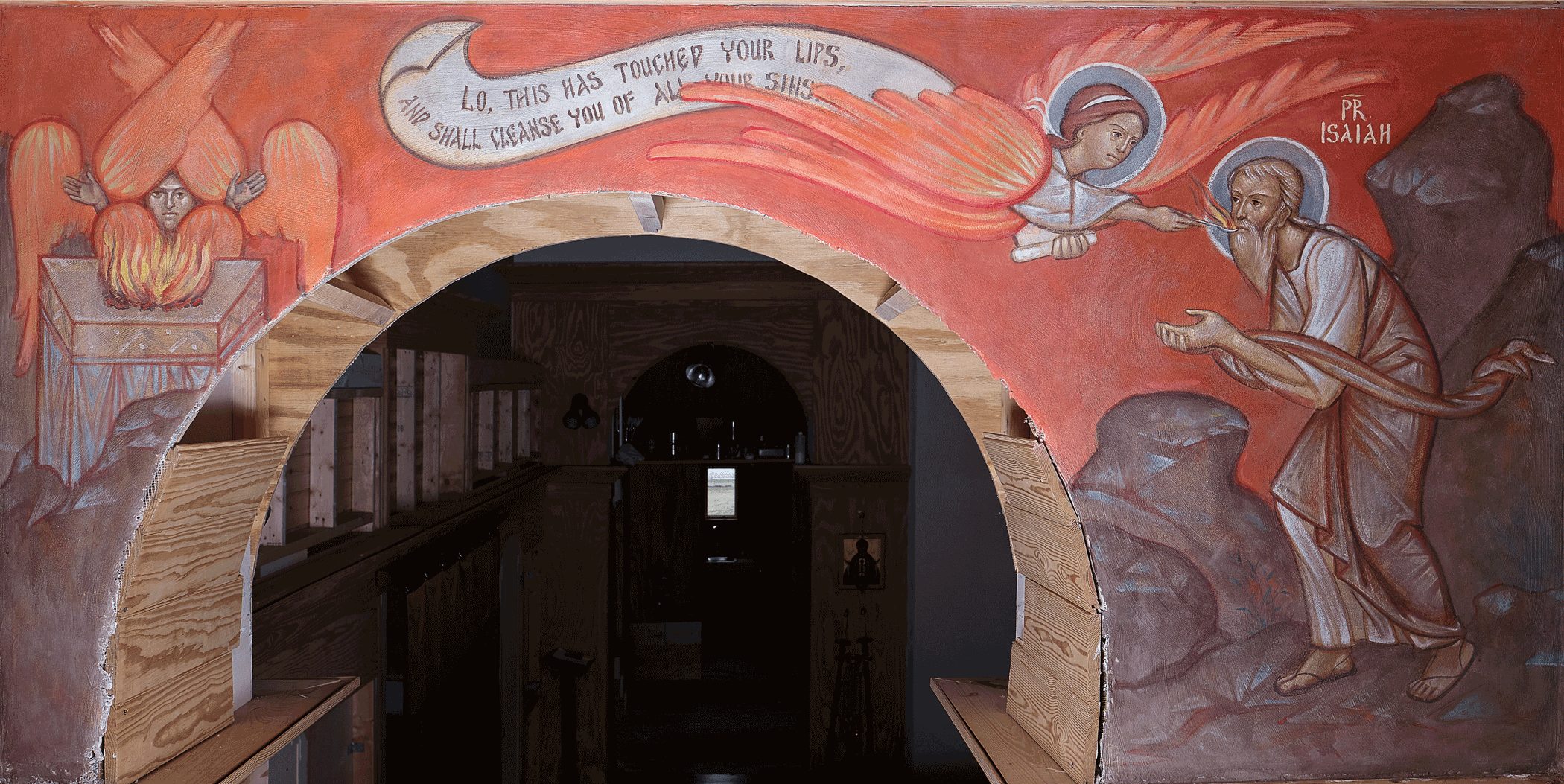

The mural on the north wall, with the (as yet unfinished) arched door into the main sanctuary of the church.

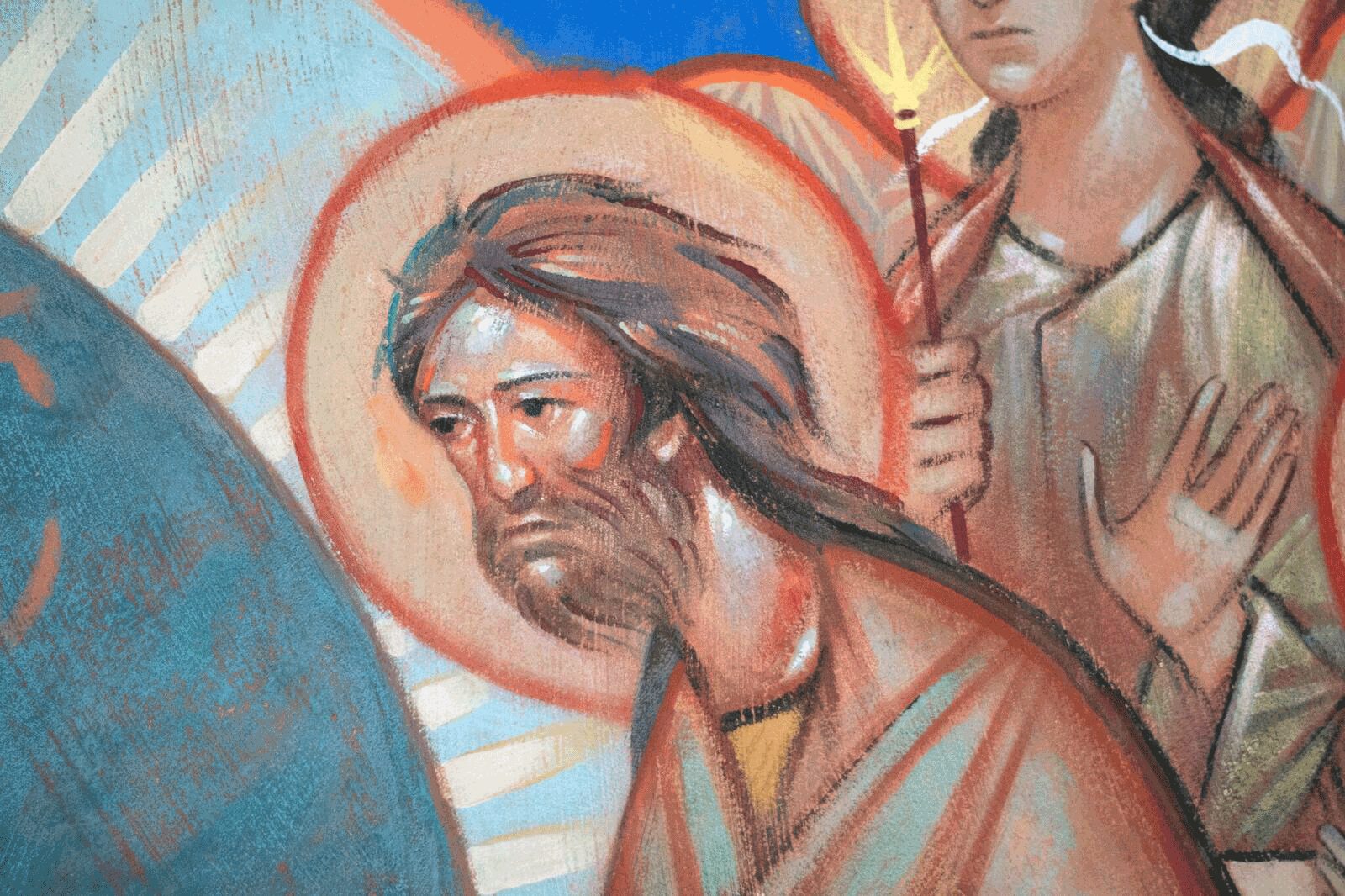

If the east wall depicts God’s self-revelation as fire, then the side walls depict the human approach, and participation in that divine fire. The north wall illustrates Isaiah chapter 6, where in an angel touches a burning coal to the prophet’s lips during an encounter with the Lord. The south wall shows the three Hebrews; Ananias, Azarias, and Misael in the fiery furnace from Daniel chapters 1-3.

In Isaiah 6, the prophet protests that because of his impurity, he is unfit to see the Lord, and his life is in danger. In response, an angel takes a coal from the altar and touches it to his lips. This is probably the most common old testament image by which we interpret the Eucharist: “Do thou not loathe my …unclean tongue, but let the fiery coal of Thy most holy Body and Thy precious Blood be to me for sanctification and enlightenment”

The response to Isaiah’s protest is written on the scroll trailing behind the ministering angel. The priest proclaims this line at every liturgy after distributing communion: “Lo, this has touched your lips, and shall take away all your iniquity, and shall cleanse you of all your sin” (Isaiah 6:7).

The story of the three Hebrew youths in the furnace is also one of encounter with God. Because of their purity of heart, the youths are not burned when the King Nebuchadnezzar throws them into the furnace. Rather, the angel of the Lord joins and protects them.

This scene is one of the most ancient and familiar images in Christian murals and hymns. Here, the youths’ gestures, surrounded by flames, relate them to the Theotokos on the east wall. Mary is the great example, the ideal human to which we all aspire. Hey inner purity allows her to be filled with divinity without harm. The three Hebrews show us how to approach that ideal: “The bush on the mount unburnt by fire, and the Chaldean furnace cool with dew, prefigured you plainly O Bride of God; for you received in your material womb the Immaterial God, and were not consumed.” 2

The West Wall

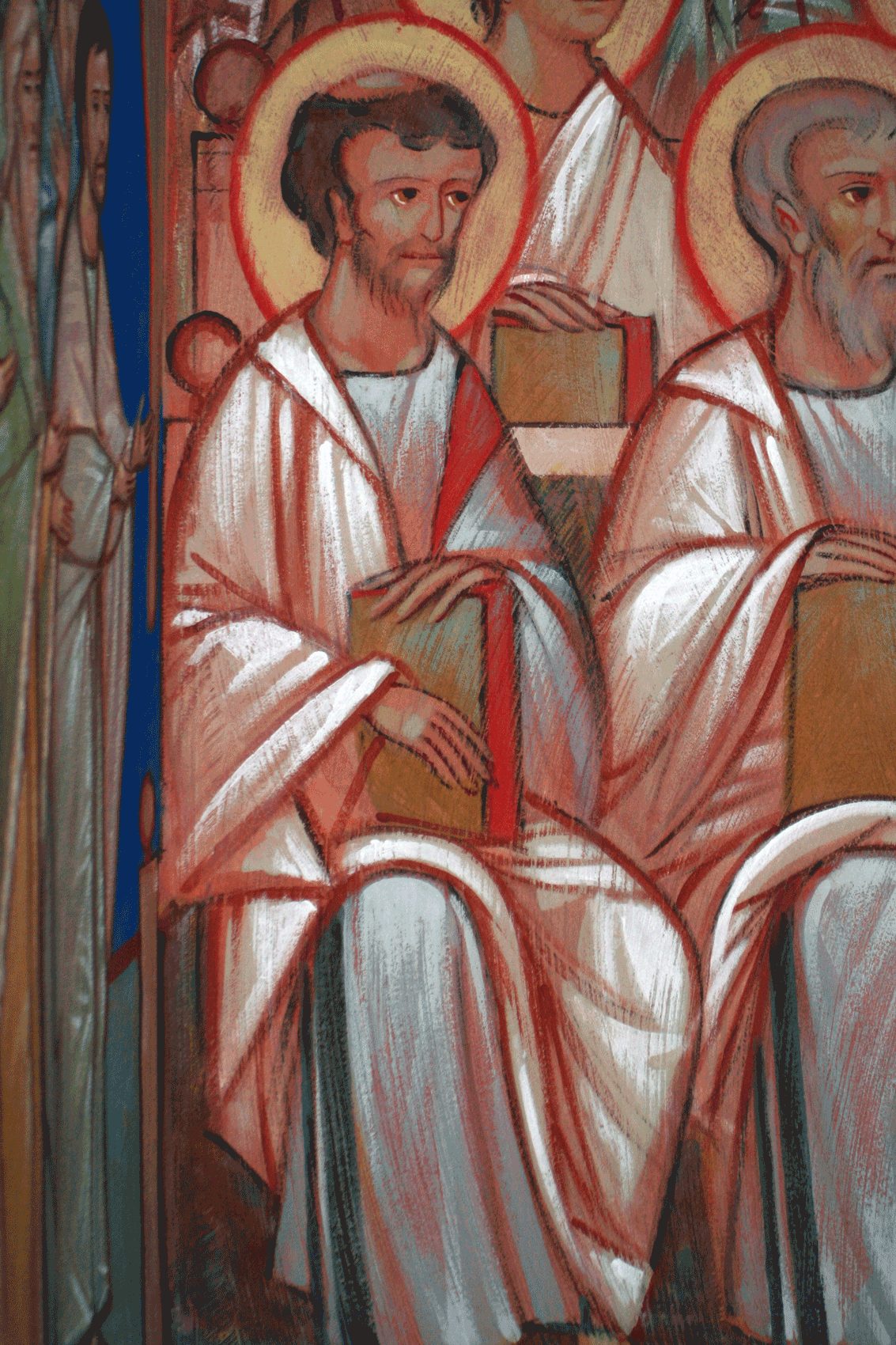

It is customary for the iconography on the west wall to relate to the act of departing from the worship space. The altar is in the east and the door exits west. In our chapel, the image of Pentecost fulfills this role. The Holy Spirit in tounges of fire comes to each disciple. The disciples are to carry this fire to the ends of the earth. The figure of the cosmos below represents the world, sitting in darkness and waiting for this light.

The prophets Joel and Ezekiel stand to either side of the image, looking on from afar. They each hold a scroll with a portion of their prophecies which we read on the feast of Pentecost. In each prophecy, God promises a new age of reconciliation, in which all people of every nation will become the chosen people of God. God will be with us directly through the Holy Spirit. Pentecost inaugurates this new age.

The icon of Pentecost is a fulfillment of the whole iconographic program, as we sing: “The Burning Bush on Mount Sinai prefigured you, O pure Virgin, for you were not burnt when bearing the Fire Divine in your chaste womb; hence, grant us, your servants to be the dwellings of God the All-holy Spirit.” 3

The Prothesis Room

As in the burning bush Chapel, the iconography in the Prothesis relates to the liturgical action that takes place there. Here, that action is the service of proskomide, wherein the priest prepares the bread and wine for the liturgy.

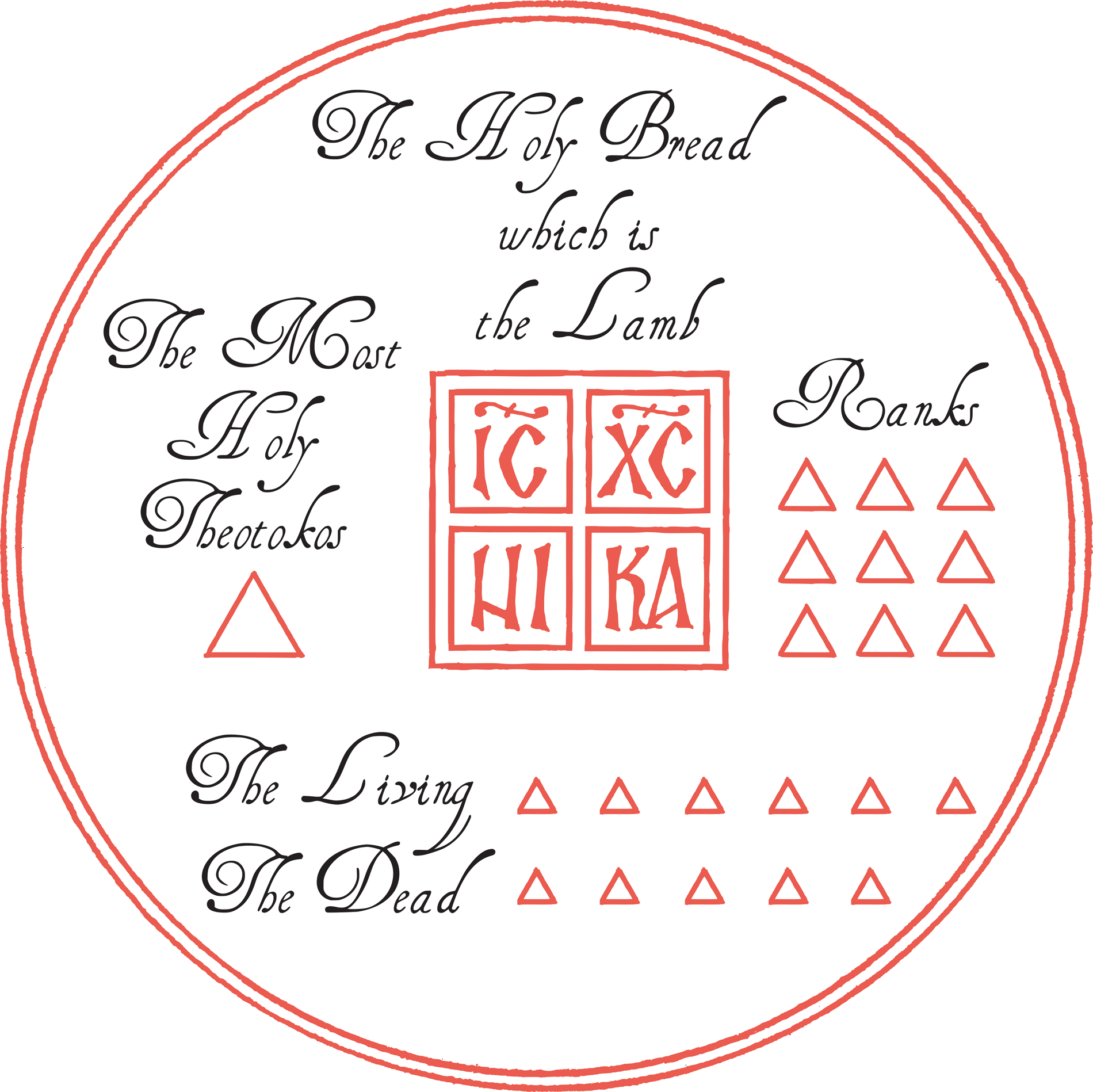

Our iconographic program began with an insight, from Fr Alexander Rentel of St Vladimir’s Seminary, that the imagery of proskomide mirrors that of the Last Judgement. A comparison of bread on the diskos during proskomide with the traditional iconography of the Judgement will make this apparent.

Diagram of the placement of bread on the diskos, (the plate used for the sacramental bread), during proskomide. The priest places these pieces progressively along with prayers, according to the order of the service.)

East and North Walls

During proskomide, the first and largest portion of bread that the priest places is the ‘Lamb’, as in the above diagram. 4 It bears the greek inscription of Christ’s name. This portion, sitting on the center of the diskos an on a throne, is the bread of communion during liturgy. The priest pierces this piece of bread and intincts it with wine, with the words, “One of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and immediately there came out blood and water.” 5 In the mural directly above, Christ appears with pierced hands and feet, and the same greek inscription. The circular shape of the mandorla surrounding him mirrors that of the diskos.

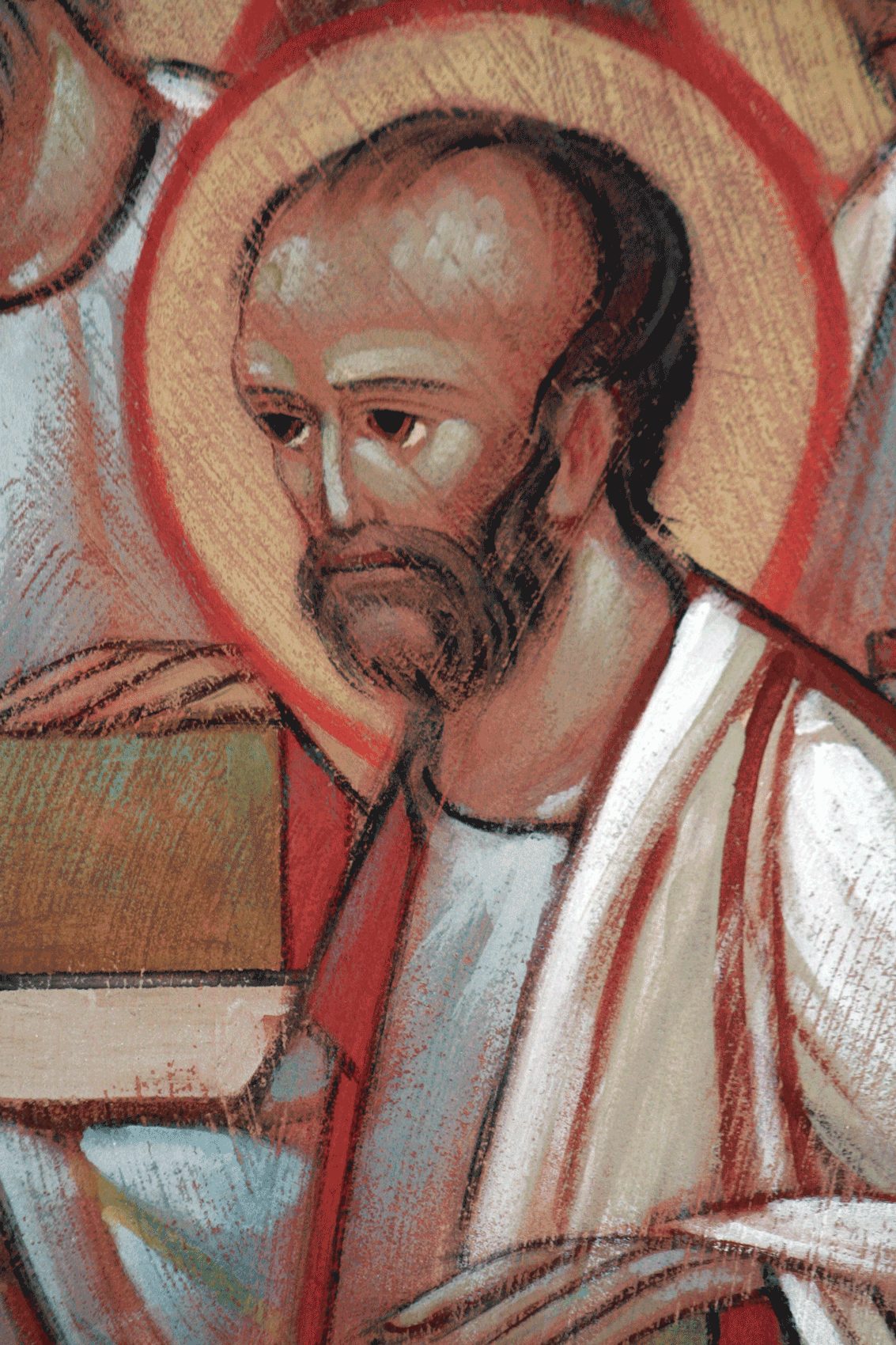

Next, the priest places a particle of bread to the right of the Lamb, which represents the Theotokos. He says, “The Queen stood on Thy right side, arrayed in golden robes all glorious.” 6 After this he places a particle on the left, representing St John the Baptist. These first three pieces form the deesis, one of the crucial images of Orthodox iconography. The deesis also forms the core of Last Judgement icons. (Jonathan Pageau offers a profound explanation of this in his talk, The Icon of The Last Judgement).

The deesis image often expands to include apostles, angels, and saints according to rank. This is true as well in the service of proskomide, wherein subsequent particles commemorate each of these ranks. Likewise, icons of the Last Judgement present this reality, with apostles and angels surrounding Christ’s throne, and saints approaching in groups. In our mural, these saints approach in order of their commemoration on the diskos: prophets, hierarchs, martyrs, ascetics, unmercenary healers, and authors of the liturgies. Joachim and Anna stand at the end. We included saints whom the proskomide text names specifically, as well as others who have particular importance for the community.

Finally, during proskomide, the priest prays for people by name, both living and dead, placing a particle for each person below the Lamb on the diskos. The figures of Adam and Eve kneeling at Christ’s feet mirror these particles’ placement.

South and West Walls

On the South wall, an angel rolls up the scroll of the heavens as in Revelation 6:14. Beside him, another angel blows a trumpet to rouse the dead from their graves. Death appears as a terrible beast like Jonah’s sea monster. Figures like these are almost always found in Last Judgement iconography.

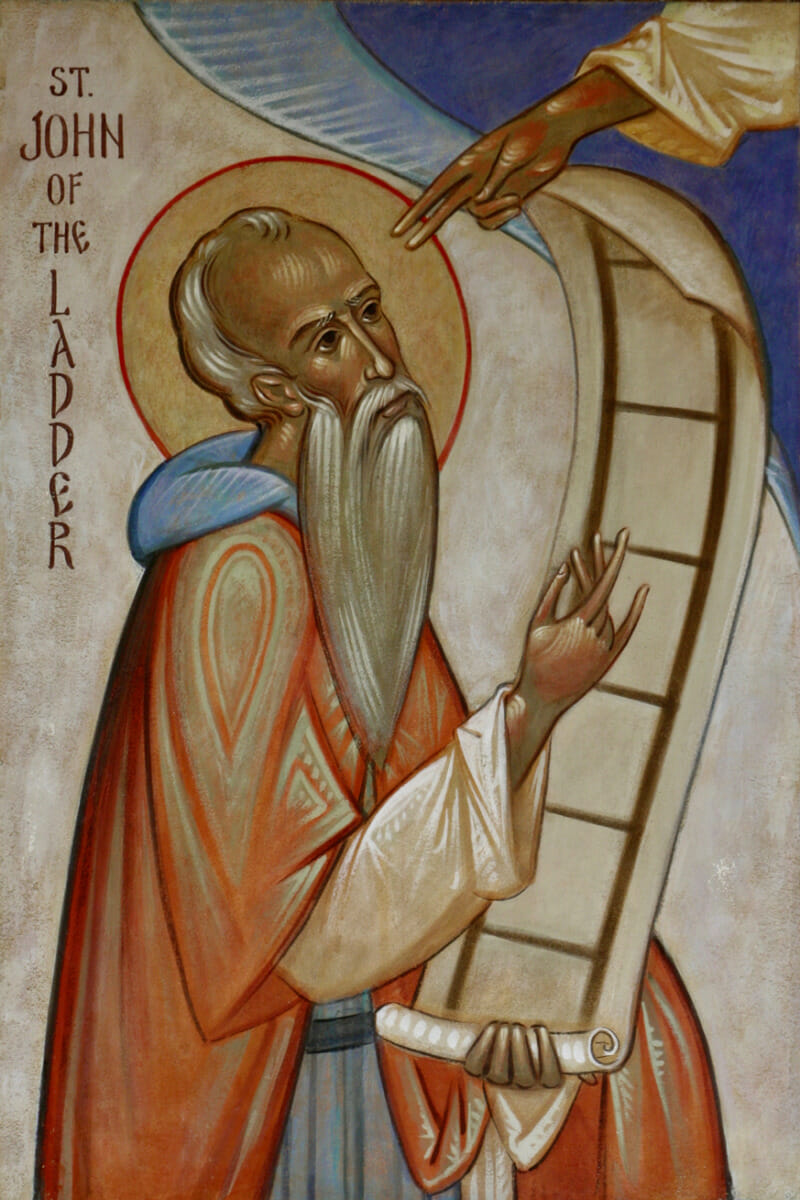

Likewise, icons of the Judgement use various images to show how our choices in life bring us closer to or farther from Christ. Here, because of the temple’s dedication to St John of the Ladder, we chose the icon of the Ladder of Divine Ascent to fulfill this role in the program. St John himself appears at the top of the ladder.

The remainder of the west wall represents paradise, in the usual way for Judgement icons. A cherub guards the door of paradise with a flaming sword. The first to enter is the thief, cross in hand, to whom Christ said, “Today you will be with me in paradise”(LK 23:43). Abraham, with the saved in his bosom, represents paradise as described in Jesus’ parable of Lazarus and the rich man (LK 16:19-31). The Mother of God also personifies paradise, as the place where God and humanity unite.

This iconography of paradise especially relates to the culmination of the diskos imagery. During liturgy, after communion, the deacon gathers all the particles representing the saints, angels, the living, and the dead; together into the chalice with the words, “Wash away, O Lord, the sins of all those remembered here, by thy precious Blood, through the prayers of thy saints.” 7 The prayers that accompany this action are hymns of paradise:

“Shine, shine O New Jerusalem: the glory of the Lord has shone on thee. Exult now and be glad, O Sion. Be radiant, O pure Theotokos, in the Resurrection of thy Son.” 8

Notes

I executed these murals with silicate paints. This kind of paint has all the visual and archival advantages of fresco without the difficulties that arise from the necessity of painting on freshly laid plaster. The deep chemical bond the paint forms with mineral substrates can hold up to harsh outdoor conditions. And the mineral matte finish, like that of fresco, is ideal for murals, where a sheen is undesirable. I believe it is the best option for iconographic murals in most circumstances. Feel free to ask me about it.

I am particularly indebted to Andrew Schwark, who took many of the photographs of the Burning Bush chapel; and to Iain Thorpe, who did the same for the Prothesis. This was a great gift.

If you would like to donate to the project, click here, and give to the iconography fund. Or, send to our address at 213 Roper Mountain Rd Ext. Greenville SC 29615. I will be posting articles occasionally as the mural project continues.

Footnotes

- Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses. Trans. Everett Ferguson and Abraham J Malherbe. Paulist Press, NY 1978. p.59 s.21.

- From the Menaion from Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Boston, Mass. Matins canon for September 8, irmos of ode 7.

- From the Menaion from Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Boston, Mass. September 4 exapostillarion.

- This image was drawn by Andrew Gould, for the Hieratikon beautifully crafted by Hieromonk Herman and Vitaly Permiakov, cited below.

- Hieromonk Herman and Vitaly Permiakov, eds., Hieratikon: Liturgy Book for Priest & Deacon, Vol 2 [South Canaan, PA: St Tikhon’s Monastery Press, 2017], 74.

- ibid, 76

- ibid, 151.

- ibid.

They are really beautiful. The matte effect of the paint is very important. The drawing is simple and superb and the painting style is traditional with a slight modern look that is a nice balance. Very good work!

Thanks, Bob! The encouragement means a lot!

Seraphim,

Your paintings show an inner radiance that is so beautiful … it seems to bring forth the grace of the individual at the same time it melds all together in a feeling of the underlying faith. So beautiful!

Lorry Wolfe

Thanks Grandma! You could not have given a more thoughtful word of encouragement

The murals are looking excellent! I like to see that you’re using different colors for halos, as needed compositionally. The overall execution looks fresh and spontaneous. Looking forward to seeing more as you move on with the rest of the project. I have one technical question: did you transfer scale cartoon drawings onto the walls or did you work the composition directly on the wall?

Thank you Fr Silouan! It is good to hear this to you. And thanks for your question. Yes, I draw small drawings to scale, and transfer them by eye, usually using a loose grid. In some cases, as especially in the prothesis here, the sketches are very simple and informal; just enough to suggest the basic placement of things. In this case, a lot of the drawing decisions happen as I work on the wall. Other times, I have somewhat more precise drawings, or drawings of particular figures. Even here, I am drawing it anew on the wall, and a lot changes in response to the experience of seeing everything together on the larger scale. I like to do the initial drawing on the wall with the brush attached to a long stick, so that I can see the image as a whole. I am too intimidated to work a composition directly on the wall, where every mistake is so much bigger and harder to correct! Maybe someday? This question seems to me akin to the priests’ question of preparation for sermons.