Similar Posts

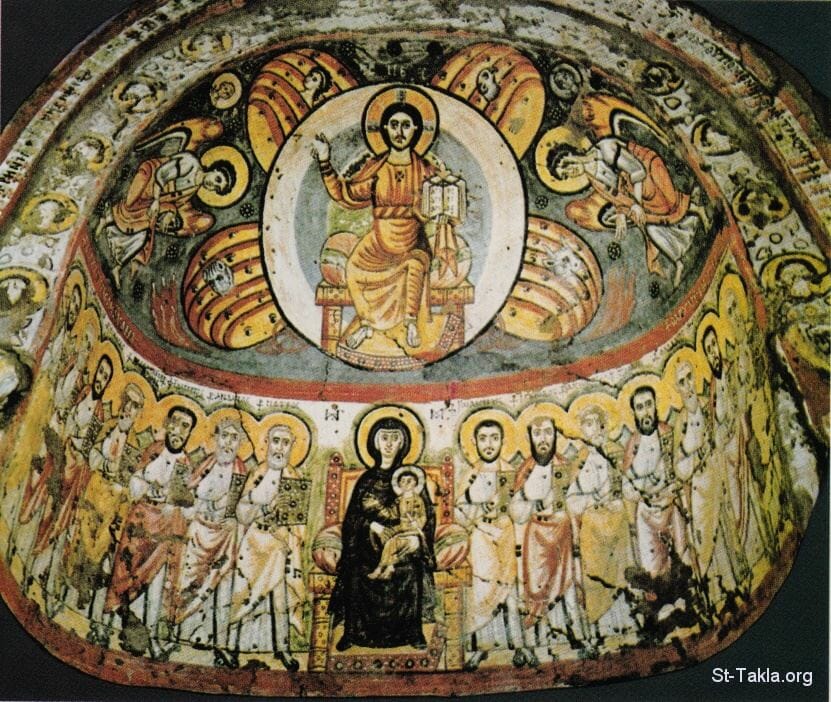

The Coptic tradition of iconography is one of which we know very little about in the West. So many of the ancient monuments were destroyed or came to disrepair as Copts in Egypt were subject to Islamic rule in the 7th century. It is only recently that the old monuments are being rediscovered, cleaned and restored properly. These jewels of ancient art shine as testimonies to the vibrancy of this tradition. There are also those who have attempted to renew and adapt this ancient art for modern times, at the forefront of which is the late Dr. Isaac Fanous and the Neo Coptic style of iconography. I am very happy to have the opportunity to present an interview I did with one of the most prominent representatives of this school, Dr. Stephane René, a disciple of Fanous who lives and works in London. He has painted several churches and icons and is also the director of the Sacred Space Gallery under the patronage of the Anglican bishop of London. He took some time to answer our questions as he prepares for an exhibition of his own icons for the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts (PSTA), where he also teaches.

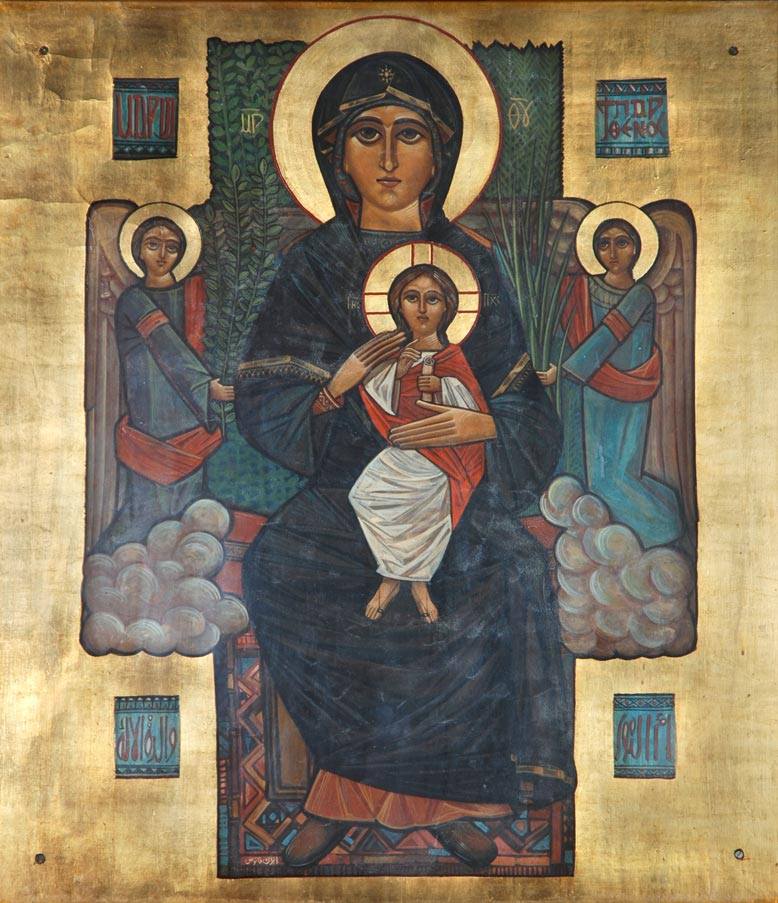

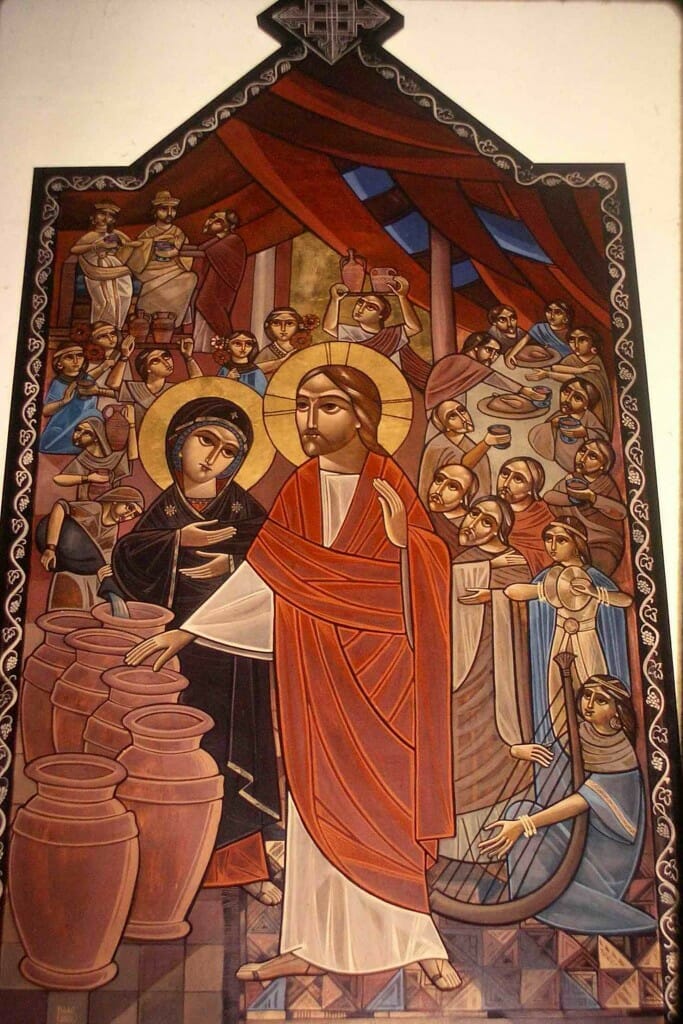

Pageau – The second half of the 20th century saw a rediscovering and renewal of sacred arts. Certain figures shine, like Photios Kontoglou for Greece, Leonid Ouspensky or Mother Juliana for Russia. One of the figures that has shone like a beacon for Coptic art has been Dr. Isaac Fanous. His creation of the Neo Coptic movement has reinvigorated Coptic iconography and his style is being continued by several students. The style is very vivid, referring all at once to ancient Christian prototypes, to modern composition and abstraction, but also to a pan-Egyptian identity. You studied and worked with Dr. Fanous. Can you tell us a bit about how you came to Neo Coptic iconography, how you learned, and we would also like to get a better glimpse of Dr. Fanous, a figure that stands large but of whom we know little about in the West?

René – First, I would like to thank OAJ for requesting this written interview about the Coptic iconographic tradition, which I have been studying and practicing for more than half my life. The process of answering your pointed questions have raised many issues that could not be properly addressed in this format. However, I have tried to be as accurate, objective and succinct as I could and hope that I will not offend anyone in my candid answers and analysis.

After years dreaming of rediscovering the Coptic iconographic tradition, Isaac Fanous had become convinced that the only way to retrieve the technique, visual grammar and symbolic vocabulary of Coptic iconography was to study it under a master from a living Orthodox tradition. It was during a two year restoration course at Le Louvre in 1962, that Isaac Fanous found the Russian iconographer and theologian, Leonid Ouspensky, and took this God sent opportunity to study iconography under him. Thus, he enrolled on Ouspensky’s course at L’Institut Saint Serge in Paris, an institution under the aegis of the Russian Patriarchate in exile.

It was there that he met Russian theologians Vladimir Lossky and Paul Evdokimov, who were friends and colleagues of Ouspensky, and also taught courses at the institute. These heavyweights of Orthodox theology/iconology had a profound and lasting effect on Fanous and acted as a catalyst in the creation of the new Coptic canon. After completing the course, he eventually returned to Egypt equipped with the proper tools to start the revival of his ancestral iconographic tradition in earnest. His time in Paris represents a watershed in his timeline, creating the “pre-Paris” and “post-Paris” periods.

Apart from being an unusually talented individual, the fact that he formally studied Orthodox iconography/logy, de facto separated him from his Coptic peers back in Egypt, who unequivocally refused to study under him after his return, being content with copying his techniques and materials, but not the theory, which they regarded as unimportant. Is a man ever a prophet in his own country? (For more background, see Contemporary Coptic iconography, Monica Rene, Coptic Civilization, edited by Gawdat Gabra, AUC 2013).

The importance of Isaac Fanous however, cannot be over-estimated with regard to the glorious renaissance of Coptic iconography in the late 20th century. I think it is even fair to say that were it not for him, there would have been no such renewal and Coptic iconography would have carried on fumbling in the dark. In the years after the 1952 Arab nationalist revolution headed by Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Coptic intelligentsia found increasing interest in rediscovering their cultural heritage and identity. In 1954, in this spirit of renewal, the Institute of Coptic Studies (ICS) was created specifically to fulfil this need and comprised all the main disciplines of Coptology, including art. At about this time, Fanous began the long process of retrieving a heritage buried under centuries of desert dust. This humongous task was fulfilled over 40 years, gifting the Coptic Church with a recognisable, beautiful and authentic sacred iconography, on par with the great Eastern Orthodox artistic tradition. To return to your question, the answer is an emphatic yes, Isaac Fanous is indeed the Kontoglou or Gregory Kroug of the Coptic Orthodox Church. However, whereas Kontoglou and Kroug were both able to continue a tradition that had somewhat waned over a relatively short period of time, Fanous explained: “I had to bridge a gap between Bawit (Coptic period 4th-7th c.) and today”.

This he did by creating a new canon and visual vocabulary based on the old, but reinterpreted anew, a task arguably more difficult than that of his Byzantine counterparts. Another difference is that while Kontoglu, Kroug and Ouspensky were widely recognised and respected by their own people, Fanous had to struggle to be taken seriously. Although he had some important and influential supporters, he had also powerful opponents. A good example of the nature of this struggle is the iconography of St Mark’s Cathedral, Cairo, which should have unquestionably been given to him, but was instead given to the very people who refused to study under him on his return from Paris. The project fell through and only a mediocre iconostasis was eventually erected. A new attempt is presently underway to finally adorn the cathedral in time for 2018, to mark the 50th anniversary of the laying of its foundation stone by St Kyrillos VI. Let us hope the right decisions are taken this time around…

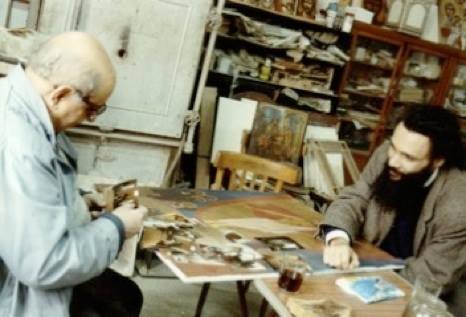

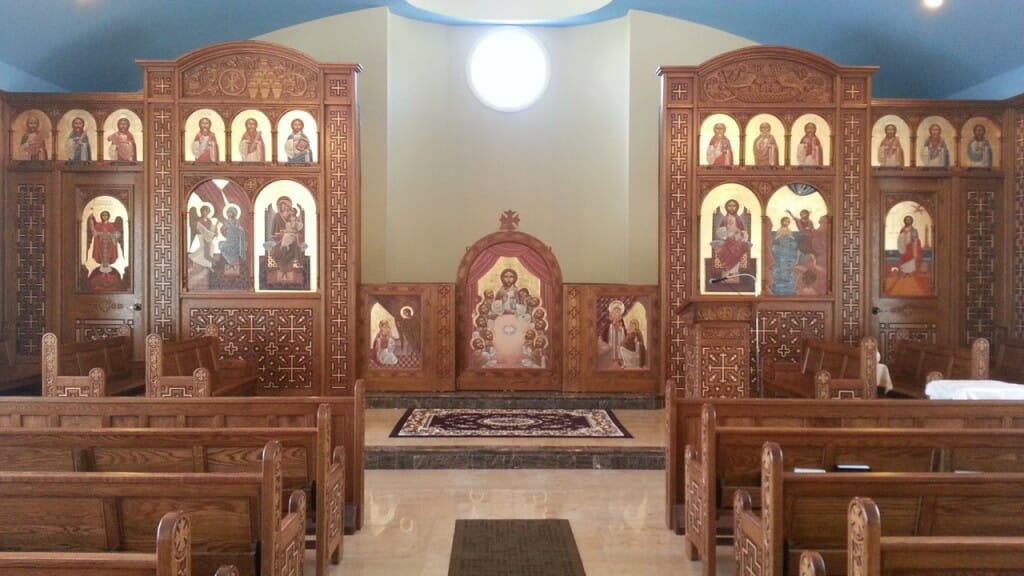

I first became acquainted with the work of Isaac Fanous in 1982, when my wife Monica and I started attending liturgies at St Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Church in London. I have been a deacon (psaltos) there for over 30 years now. The iconography of St Mark’s church was completed a few years earlier, between 1976-78. It was Prof Fanous’ first major commission outside of Egypt. While standing in the choir, facing the iconostasis during the liturgy, I became fascinated by these beautiful icons that seemed to emanate a warm golden light and had a timeless quality. Looking at them gave me moments of inner silence. We took our first trip to Egypt in the Summer of 82, during the feast of St Mary and it was there that we eventually met him at his studio at the ICS. It was to become a kind of second home for the following seven years.

While studying with Isaac Fanous, I met other students who attended a weekly 2 hour class in icon painting on Fridays. These he referred to as pupils. They were mainly women who enjoyed icon painting as a hobby. He also had assistants who came during the week to help with large panel preparation, gilding and the laying of proplasmos (underpainting in dark colours). I was one of those for a period and enjoyed every minute, being in constant (and sometimes silent) conversation with the master. Of those I met during this time at the institute, few are still active today. Ashraf G. Fayek and Guirguis Boktor were two. Ashraf now lives in Australia and works under the bishopric of Melbourne. His style is generally “fanoussian” with a tendency towards standardisation, decoration and the free use of modern media and materials, like acrylics and MDF. Guirguis Boktor lives in California, where he originally came as an assistant to Prof. Fanous while he was working on the large mural paintings at the Holy Virgin Coptic church in Los Angeles in the 1990’s.

Pageau – Form the outside, it seems as if Neo Coptic iconography has received an almost unanimous acceptance within the Coptic church. Is this perception accurate? What is the general reaction to the new style and how have you found that clergy and parishioners identify with the new art?

René – The perception of a “unanimous acceptance” is unfortunately quite inaccurate. When I first saw the icons of Isaac Fanous, there was absolutely no doubt in my western mind that this was the authentic canonical iconography of the Coptic Church. I imagined that, like in Greece, the tradition had been passed on unchanged over generations. However, on our first trip to Egypt, we quickly began to realise that this style of iconography was not at all the norm and even rather disliked by a large majority of Copts who considered it “naive” and “childlike”, preferring Western religious models instead. I thought the whole thing quite strange then, but I am almost used to it by now.

Generally speaking, the majority of people in the church find it difficult to identify with the Neo Coptic style and most seek and relish the realistic sentimentality of Italian(esque) art. In fact, the kitschier, the better.This state of affairs is due in part, to two hundred plus years of cheap and ubiquitous Catholic imagery flooding into Egypt with the onslaught of Western missionaries. Consequently, the local production and use of traditional icons quickly waned between the early to mid 19th century. The majority of monuments built during this period are adorned in the preferred Italian/Roman style, complete with blond-haired, blue-eyed meek and mild Jesus, with piggy pink cherubs flying about on clouds, that even the Catholic church rejected at Vatican II. This style however, most Copts consider “beautiful” to this day. A case in point is the new Coptic Cathedral in Sharm-el-Sheikh, built in the last few years at high expense and regarded as a thing of great artistic merit. H.H. Pope Tawadros recently decided that it was not appropriate to use this style of art in Coptic church buildings any longer, especially in the diaspora. He did not however, stipulate what should be its replacement.

The lack of education in iconology is unfortunately not restricted to the congregation, but also extends to the hierarchy of the church. Unlike the Russian Church, for example, who is known to foster and nurture the knowledge and appreciation of iconography among its clergy, Coptic clergymen are generally left to their own devices, deciding according to their own personal taste what kind of art should go in a new church building under their jurisdiction. This of course does not work, as proudly displayed in countless churches at home and abroad. Perhaps another contributing factor is that Coptic priests are not required to attend seminary, but are primarily trained in pastoral care, thus lacking the opportunity to deepen their knowledge and appreciation of church traditions, like the liturgical arts. A recent article written by Fr Moses Samaan, posted on his blog http://becomeorthodox.org/the-slow-death-of-iconography-in-the-coptic-orthodox-church/ laments the “Slow death of Coptic Iconography” before our very eyes. It is the first time a Coptic clergyman has openly commented critically on the state of Coptic iconography and the general attitude towards it. Perhaps a change is slowly emerging…

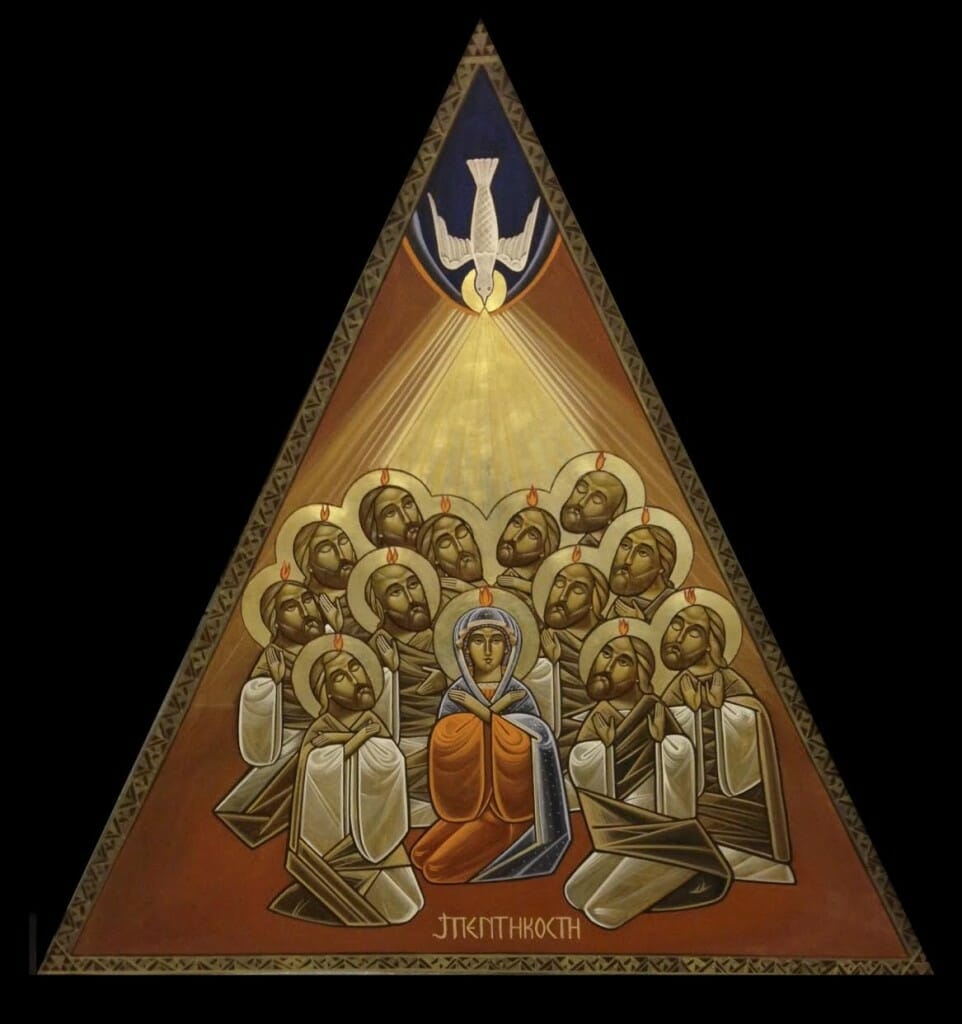

Pageau – In the Byzantine/Russian tradition, although there is some room for improvisation, certain types, such as the festal icons or other major types are pretty resolved in their composition and cannot take too much change. In looking at Neo Coptic iconography, there seems to be a greater willingness to improvise in terms of composition, figure placement and with adding or omitting certain details. We are also used to certain tropes, poses, details. For example we show feet and hands as much as possible, the type of thing which seems to be more flexible in Neo Coptic icons. I am curious to how you engage the ancient models and what decision process you take in the composition your icons.

René – One cannot look at Coptic iconography through the same lens as Byzantine iconography. The canon has been maintained and nurtured in Byzantine iconography from the earliest period. This is not the case with Coptic iconography, whose canon, established during the Coptic period (4th – 7th c.) was not allowed to develop and flourish, due to certain historical factors, not least of which is the advent of Islam and the systematic oppression of Egypt’s indigenous Christian people and their culture.

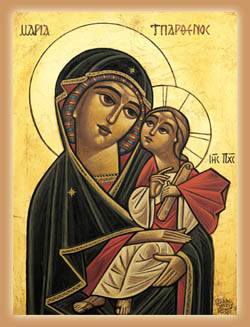

There are many individuals today who call themselves “Coptic iconographers.” In truth most have no training or relevant qualifications. Many come from computer graphics background, cartoon/caricature, or college art departments. They apply what they have learned in secular/commercial art to iconography, to disastrous effect. The all important relationship between master and student is a foreign concept to most and iconography is practiced mainly as an individualistic endeavour or as a career move in some cases. Iconography is now being considered a viable occupation (read business) for young people, especially in the last 10 years or so, and more so since the departure of the master in 2007. This becomes quite obvious if one types Coptic icons in the Facebook search box. Some images with huge phone numbers plastered across them more reminiscent of a supermarket place than a sacred object. Many youths have now taken to “creating” new icons on the computer using graphics software. I am often quite irritated after seeing certain heretical horrors and do make strong comments. I once had to rebuke such a Facebook iconographer for putting the “eye of Ra” on the Virgin’s maphorion instead of the six pointed stars symbolic of her virginity, before and after the birth of the saviour. He became offended by my disapproval and said that he was a native Copt and a descendant of the Ancient Egyptians and this was part of his heritage and identity. I explained that ethnicity and race are irrelevant in the context of the Orthodox faith and iconography, but to no avail. Another example worth citing is the 2013 Royal Mail Christmas stamp, featuring a Coptic Virgin and Child. In this case no stars were placed on the Virgin and the design broke all the rules that govern Neo Coptic iconography, which it was supposed to represent. In a sense, such work does unfortunately represent the current state of aimlessness and confusion surrounding iconography in the contemporary Coptic Church.

2013 Royal Mail stamp without the usual stars and with awkward composition. Notice for example the prominent brow of the Virgin.

To return to your original question about composition and improvisation, the answer is that Coptic iconography is presently reverting to pre-Fanoussian levels and in a state of complete flux. I’m afraid improvisation is the default setting and as no one seems interested in correcting it, further decadence will naturally follow. It should not be so, because a foundation was provided, upon which an iconographic fortress could be built (Fanous).This is one of the most perplexing issues. Let us be clear: there is no iconographer in the Coptic Church currently capable of filling Fanous’ shoes. He was not only a gifted artist, he was a visionary, a mystic, a theologian, a visual poet, the likes of which are not often seen. One of his dearest wish he often mentioned to me, was the establishment of a Coptic School of iconography, where new generations of iconographers would be formed in both practice and theory. He used to speak of iconography in terms of form and essence, i.e. practice and theory, symbolic of body and spirit. By “essence” he meant the soul of iconography, its unseen, or occulted aspect, e.g. its theology, the correct use of symbolism and the geometry that ties them all together into a meaningful, beautiful and sacred icon.

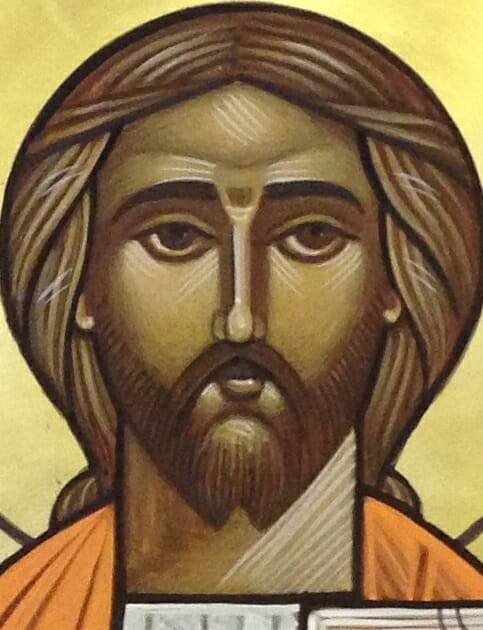

Holy Face by Stephane Rene, 2013

This face represents the standard canon for the human face of God the Son, for the contemporary Coptic style of iconography and is designed and painted using the principles and geometry established by Isaac Fanous.

For me, the designing stage is crucial, because it represents the support, the architectural grid of the icon, if you will. Here, the geometry is established and the icon finds its form. Just as there cannot be a great building without a great plan, there cannot be a good icon without a good design. After designing, lighting becomes of paramount importance. Iconography is all about light, the “heavenly light”, as Prof Isaac called it. I have sought that heavenly light for the last 30+ years and hope to continue my search for the next 30, God willing…

Pageau – Just as many of our collaborators at OAJ, you also seem to be involved with The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts. Can you tell us a bit about how this came about. You are having a show with the School in the fall. Can you tell us a bit about this show, its scope and its focus.

René – My association with the Prince’s School of Traditional Art (PSTA) goes back to my time at the Royal College of Art (RCA) during the 1980’s. My PhD supervisor was Prof. Keith Critchlow, Director of the Visual Islamic and Traditional Arts Department (VITA). Incidentally, the department was originally called Visual Islamic Arts (VIA), but the “Traditional” was added shortly after I joined, to take into consideration the non-Islamic sacred traditions, such as Coptic iconography. Prof. Critchlow, original founder of VITA, is renown for his unique approach to the teaching of sacred and traditional arts of the great world traditions, with emphasis on Islam because of its use of geometry. Shortly after I received my doctorate in 1990, the whole department was moved from the RCA to form the nucleus at the Prince of Wales’ Institute of Architecture (POWIA), which opened in 1993, under the patronage of H.R.H. Prince of Wales. An icon of King Solomon as patron of architecture was specially commissioned by the institute for the inauguration. I became a tutor and iconographer in residence at POWIA, enjoying a large studio on the first floor with view on Regent’s Park for a year. Sometime later POWIA became PSTA and moved again to the current premises in East London’s Charlotte Street. I was instrumental in the introduction of Christian Art, and more specifically iconography to VITA and PSTA. In 2006, I curated the first exhibition of Contemporary Orthodox iconography, Sacred Iconography; A Living Tradition, at the school’s gallery. Russian, Greek, Romanian, Ethiopian and Coptic icons were exhibited side by side with explanations about their similarities and differences. This was very well received by the general public and H.R.H. showed his special appreciation by paying us an extended visit. Since the event, the school has introduced more Christian art into its MA and PhD programmes and provided momentum for the creation of the School of Liturgical Arts. I have subsequently tutored some excellent doctoral research students in Christian art, such as Sasha Aleksejevas, the bronze icon specialist recently interviewed by OAJ, whose progress I have been following as his thesis advisor. Another is Adrian Iurco, a talented Romanian fresco painter and one of our newest doctors, who originally approached me through a mutual friend iconographer on Mount Athos. I hope more Christian liturgical artists will come to do research at the school, enriching our knowledge and appreciation of our Christian artistic heritage.

My upcoming exhibition is partly a reaction to the current dynamics regarding Coptic iconography discussed above. I have not had an exhibition in 10 years, but felt it would create a needed opportunity to share and discuss this lesser known tradition with a wider public, as it is written: “Neither do men light a lamp, and put it under a bushel, but on a lamp stand…” (Matt 5:15). In this respect and in view of the ongoing destruction of Christian heritage in Egypt, I thought it appropriate and relevant to mount such an exhibition at this time. There will only be a few works on display, so it is a small exhibition in terms of quantity, but I hope the quality will make up for it. There will be a lecture during which I will briefly explore various aspects of Coptic iconography, such as its canon of proportion, the use of symbolic geometry and symbolism, as well as the more general function of the icon as liturgical art.

Three Youths in the Furnace, Stephane Rene 2014. Sts Mary and Abraham Coptic Church, St Louis Missouri

Christ Pantocrator and the 24 Elders of Revelation 2001 by Stephane Rene, St Mary of Zeitoun Coptic Orthodox Church, Vienna, Austria

———————–

For those interested in pursuing the work of Stephane René, please follow the links below.

- His website: http://www.copticiconography.org/welcome.html

- The upcoming Show at PSTA: http://www.psta.org.uk/news/88/

- Sacred Space Gallery: http://www.sacredspacegallery.com/Home.html

These are so magnificent. I have always been drawn to Coptic Icons but theseare to the most beautiful I have ever seen.

These icons are of such beauty. Their celestial quality and perfection raises the mind and heart to God – the onlooker is filled with praise for God and the gift he has bestowed on the artist.

As a newly illumined Orthodox Christian (Antiochian) I know that there are theological differences between Eastern Orthodox and Coptic Christians, but know not the extent. How, if at all, do those differences play out in the iconography? Can one be EO and use Coptic icons in his prayer corner? Perhaps the latter is an “ask your priest” question…

It is very interesting to read this history of the appearance and subsequent struggle of this ‘Neo-Coptic’ school of iconography. Considering the reluctance of the Coptic faithful to embrace this style, it seems we should ask the following question: Is this reluctance due merely to an affection for Italianate painting, or is it perhaps due to something intrinsically problematic with the Neo-Coptic style?

To my eyes, Neo-Coptic iconography looks distinctively 20th-century. It does not look very much like the medieval frescoes in Egyptian monasteries. In particular, the tendency to stylize everything, even facial features, as dark angular lines, is something I do not recall seeing in any historical Coptic or Orthodox art. (If there a precedent, please let me know what it is). However, this style of drawing is highly typical of 1960s-70s Christian art – the sort of graphic illustrations and stained glass windows that were ubiquitous in Catholic and Protestant churches.

I do not mean this observation derisively. I am only observing a stylistic trait, and style in and of itself does not make a good or bad icon. In fact, we can observe the same sort of modern eccentricity in the work of the early-20th-century French-Russian iconographer Gregory Kroug. His work is full of modernistic affectations that are distinctive of 20th-century avant-garde French painting. His icons are masterpieces, but few would seriously suggest that his style is the ideal model for widespread use.

So I wonder if Neo-Coptic iconography should be considered similarly – it’s a somewhat inventive style of painting, which, in the hands of a master, can be very good iconography, but which might be ill-suited as a style for lesser artists to imitate-hence the plethora of very bad imitation Neo-Coptic painting.

I tend to think that if there were a school of Coptic painters whose work was stylistically more at the center of the tradition (meaning work that more closely resembles the frescoes at the ancient monasteries), then Coptic churches would more widely accept it, and student iconographers would more successfully imitate it.

Dear Andrew,

thank you for taking the time to post a comment. That this style has certain distinctive features pertaining to the art of the late 20th century is undeniable, which is precisely why it is sometimes termed the “neo” or contemporary style. From your remarks (notably about the work of Gregory Kroug, and your use of the word “eccentricity” in describing the work of Fanous) should I assume that you are a Byzantine purist? As I mention in the text however, it would not be appropriate to judge this style of iconography according to Byzantine standards. The plethora of bad imitation Neo-Coptic icons you rightly refer to is to a large extent due to the lax attitude of both, clergy and would-be iconographers regarding iconography and iconology, as a serious subject of study. As long as this endures, there will be no positive development in Coptic iconography. Your comment “but which might be ill-suited as a style for lesser artists to imitate” is IMHO as valid for the Byzantine style as the Coptic, as demonstrated by a similar (but fortunately not so profuse) plethora of bad Byzantine iconography by untrained or poorly trained individuals or those of lesser artistic talent. The main difference is that if one really wishes to study Byzantine iconography seriously, there are proper schools to do so. There is none in the Coptic church.

Your comment “the tendency to stylise everything, even facial features, as dark angular lines, is something I do not recall seeing in any historical Coptic or Orthodox art.” These “dark lines” are contours, a ubiquitous feature of Coptic art throughout the ages. From 6th c. Bawit, to the frescoes of the 9th c. Red Monastery church, or those of St Anthony’s Monastery from the 13th c., contours have been used by Coptic artists. I think “abstraction” is a more appropriate word in this context, than “stylisation”. Whether Greek, Russian, Coptic or Ethiopian, abstraction of the human figure and earthly reality has always been used in iconography, specifically to emphasise the other worldly nature of what is being depicted, which is precisely what Italian/Renaissance art reversed. On one level, it could be said that the more abstract the style is, the more spiritual it is, and conversely, the more realistic, the more worldly, reflecting an earthly and therefore imperfect/fallen nature. Such a movement is presently happening in the Ukraine, where iconographers are engaged in extreme abstraction, reducing the human form and objects to mere geometrical shapes, yet keeping the essence of the message. The same can be said of certain Russian schools, like Novgorod, or even the work of Theophanes the Greek, in which figures are often over elongated etc…

I see nothing intrinsically problematic with the Neo- Coptic style. You would have to elucidate a little about what you mean by “problematic”. The only problem I see, as you rightly point out, is the majority of the Coptic faithful’s quasi addiction to Italianate realism and sentimentality. Should this be left to continue simply because the faithful like it and are used to it? It does not seem to be the opinion of H.H. Pope Tawadros and was definitely not that of Isaac Fanous.

The issues surrounding Coptic iconography are many and highly complex, but I am glad some are being discussed for the first time on a serious and specialised platform such as OAJ. Thank you again for your interesting and challenging comments.

Hello Stephane,

Thank you for your interesting response. Indeed, it is important to finally discuss the question of specifically Coptic iconography, and I appreciate that you are willing to address the issue of style. Given that there is, for the most part, broad conformity between Coptic and Byzantine iconography with regards to subject and composition, I really see style as the main place in which to identify any meaningful differences that might exist.

You ask if I am a Byzantine purist. I most definitely am not. On the contrary, I personally tend to be most attracted to iconography that is near the fringes of the Tradition. I love the Novgorod school; I have great affection for folkish icons from Romania with Baroque influence; I have a particular interest in carved wood and cast metal icons from the Old Believers. However, despite my appreciation of these manneristic works, I would not recommend them as styles that should be promoted for widespread use in modern parishes. When I am asked to recommend iconography for a church commission, I recommend iconography that reflects the center of the Tradition – meaning the most classic middle-Byzantine or 15th-16th-century Russian styles. This is the sort of iconography that is recognized as Orthodox by all, and which historically existed as a sort of international Orthodox style in the middle ages.

On the question of imitation by less-skilled artists, I think there are indeed some styles that are more suited to this than others. Early-Romanesque iconography, of the sort sometimes painted by Father Zenon and Aidan Hart, for instance, is notoriously difficult, as it depends on excellent drawing skills, bold expression, and virtuosic brushstrokes. It is quite possible that this difficulty is the reason that this style of painting vanished long ago. On the other hand, the classic Russian style can be competently painted in a rather formulaic way, and students with modest artistic talent can be taught to paint acceptable icons in this manner, if they have humility and diligence. In 19th-century Russia, there were whole villages that mass-produced such icons by the millions. These icons are not great, but they’re not bad either. They just serve to show that this Russian style of painting was so standardized that almost anyone could do it. I don’t believe that the more virtuosic and mannered styles of icon painting would lend themselves to widespread production like this.

I think the matter of style in Coptic icons is only going to be settled over the long haul. There need to be many iconographers experimenting with many styles, and only over time will it become clear which styles seem suited both to the eyes of the people and to the skill of the painters.

Dear Andrew,

Thank you for your response, with which I largely agree. However, I do differ with the gist of your last paragraph about allowing experimentation with many styles. This approach may be an option when the iconographer is already grounded in a given tradition and fluent in its visual vocabulary and canon, which IMO represent the ABC of iconography. This is definitely not the case with the current situation with Coptic iconography. The very “plethora” of bad Coptic icons you describe in your previous comment, is itself the result of “experimentations” done without any care for theory. Going back to Fanous’ teaching about form and essence, the form (style) is empty if it does not contain the essence (meaning, spirit, message). Take for example the Akhmimic Coptic style (practiced in Akhmim, upper Egypt, c.1600 to c.1850 AD, a famous Archangel Mikhail from there is now in the Benaki Museum, Athens). It is a highly abstracted and simple style, sometimes dismissively called “primitive” by scholars, very reminiscent of Ethiopian iconography of the same period. However, the correct symbolic and theological content is all there, making these icons fully canonical and also extremely powerful.

What really needs to be done in my opinion, is to create a place where people can study the Coptic iconographic tradition, in the same way it is done in Greece or Russia. Then and only then, can educated “experimentation” take place, but not now. What is happening now is a rapid decadence because the blind is leading the blind as it were, trying to “create” a new style, while not even knowing one well. Please note I am not advocating that everyone should make copies of Fanous, only that his work should be seriously studied, as an ideal template. Let us remember that it is only after he had studied with Ouspensky, Lossky and Evdokimov, that Fanous was able to bring about a new Coptic iconography. Of what use is a pen if one is illiterate?

I would love to study Dr. Fanous’ work–is there a book or collection where it is gathered into a body for study?

I agree with your assessment wholeheartedly Andrew.

But I would like to return to Joshua Allen Donini’s question.

It is a very good question and hard one to answer, but we’ll give it a tentative try.

In answering I mainly have in mind the best historical examples of the Coptic style as you have described.

I think there are two aspects to the icon that we need to bear in mind.

The first is the pictorial form, or style. The second is the specific subject, theme, or narrative content, being communicated.

However, we shouldn’t forget that style also has a semantic or communicative aspect to be “read” by the viewer.

When it comes to pictorial form, traditional icons generally keep a tension between abstract and naturalistic qualities. Hence, they consist of a symbolic realism. Now, this is because reality itself consists of intelligible (noetos) and sensible (aisthetos) realms. These spheres of being are symbolically conveyed by abstraction and naturalism respectively. We can then perhaps say that pure- abstraction can imply a disregard, if not utter disdain, for things of sense or matter. While an overemphasis on naturalism is an obsession with corporeality, sensuality, or empiricism. As long as an icon finds itself between these two poles it will not go awry in what I call its incarnational metaphysics- the “union without confusion or division” of the intelligible and sensible.

Coptic icons, although predominantly leaning towards abstraction, retain a balance between the two poles just described. In this sense they conform to the tradition of Eastern Orthodox iconography. They employ a legitimate form of symbolic realism which gives expression to a very unique cultural temperament. In this sense there would be no problem in having one in the icon corner.

However, things get more complicated when it comes to the question of the subject or person being depicted and the theological message arising from these factors. It goes without saying that it would not be appropriate for the Eastern Orthodox to put in his icon corner the depiction of Coptic saints that are not commemorated in our calendar, especially those who refused to acknowledge the Council of Chalcedon. Neither would it be appropriate to have an icon of a historical event, such as a council, which marks a landmark in the Coptic opposition to Chalcedon. So discernment should be taken and the subject carefully “read” as to its conformity to Chalcedonian doctrine. Other than specific saints I am not aware of specific compositions that can be called “questionable” as to doctrinal matters. In most cases, at least when it comes to the major feasts, they will roughly follow the standard features as they have come down to us, in which case I wouldn’t hesitate to include them in my icon corner.

In terms of form we should not confuse the traditional icon with mere “Byzantinism.” There is room for other cultural temperaments.

Even though Orthodox iconagraphy can be considered as a form of art, it certainly is much more than that. One cannot invent his own style of iconagraphy. St. Luke, the first iconographer, was guided by the Holy Spirit to write his icons. Seems like maybe we should be following his style.

Dahlia Weddings and Baptisms

I agree that one should not “invent” one’s own style of iconography, but Coptic iconographers are trying to renew and adapt the ancient style of Coptic icons. Some may decide that this renewal is not successful or inadequate, but I don’t think anyone is trying to invent anything. It is possible to modify icons and change their style, for example St-Andre Rublev painted in a style that was new and modified the icon of the hospitality of Abraham by removing Abraham and Sarah, yet Moscow urged other artists to then imitate Rublev’s style and types. Also, it is very difficult to know what style St-Luke painted in, especially since the icons purported to be painted by him have no resemblance to 1st-10th century icons.