Similar Posts

Tell us a bit about your formative years; how you became interested in art and icon painting in particular.

I grew up next to a talented father, so watching him painting was the first step towards art. When I was a child I was reading my father’s art books and I can still remember how fascinated I was by my discoveries. In those early years I started drawing, painting and even copying the works that I found fascinating, mostly the works by Goya. Showing some talent at the early age I was led and supported by my family to pursue the artistic path. I attended an art high school for production of jewelry and art objects “TehnoArt”. After that I enrolled in studies at the Faculty of Applied Art in Belgrade. During the first year of my art studies, I started to go to liturgy and I stayed in the Church. Around the same time I became interested in Byzantine art. At one occasion my mentor at the Faculty of Applied Arts spoke about the qualities of the Crucifixion at Studenica Monastery and standing before the poster of that fresco I was taken by the profound beauty. It was not just the visual sensation but also his interpretation of it, that made such a deep trace into my searching soul. Nevertheless, I was still far from actual involvement in iconography. The reason I changed my course is because I hit a creative bottom and I was searching for a new direction. A friend of mine, priest Arsenije Arsenijevic, gave me advice to try at the Academy if that could work for me. I came there with no real goal or expectation, but soon everything came in its place and I opened a new chapter.

Did your training involve any kind of apprenticeship? What was the nature of your studies in Belgrade, the general curriculum of course, at the Academy of Serbian Orthodox Church for Arts and Conservation?

My apprenticeship involved learning from several great artist throughout ten years (2000 – 2010) of studies at the previously mentioned institutions, all in Belgrade. The usual art lessons, like drawing the figure or the anatomy was prolongation of previous studies, but the new field for me was theology. Beside these two major fields, part of the learning program were also Archaeology, History of Christianity, History of Art, Calligraphy, Painting technology, Sculpture, etc.

During your studies in Serbia, were there any professors or painters in particular who played an instrumental role in shaping your overall outlook and approach to iconography?

Concerning the studies of church art, as all other students at this art college, I was mostly working with Goran Janićijević (fresco-painting), Todor Mitrović (icon-painting) and deacon Srđan Radojković (drawing). Radojković was the first one who presented us the richness of Christian cultural heritage and was specially pushing forward beautiful examples from Armenia, Egypt or Pre-Iconoclastic period, as the model for our drawing studies. At his class we were drawing big scale works based on these icons, which was crucial for making a strong base as an painter. I have to thank him the most because he was the first who encouraged my interests and iconographical peculiarity. Janićijević helped me a lot with his aesthetical advices and theological inputs, further encouraging the the individuality and research. Although I learned a lot from these two masters, with one better look at my work, one can easily conclude that I was very much connected and drawn to Todor Mitrović. Even when I still had my own doubts, at the third year of my studies, he proposed to make an exhibition together with him and Mijalko Đunisijević in Otklon gallery in Belgrade, which was, besides being a huge honor, a sign that I could go on with my work and still reach something or someone on that path. I said to him recently that, when I was a student, we did not spoke to each other a lot, nevertheless, that experience being around such artist, talking with him about art and reading between lines was crucial for my growth. I also need to mention that I was influenced by my fellow students as well as many artists that I have never met, but whose work I have seen in books, internet, churches and museums.

How would you describe the revival of icon painting as you have experienced it in Serbia? What are the issues being discussed among students and professional iconographers?

I am afraid that I can not tell very much about the revival of the icon painting in Serbia from my own personal experience nor knowlegde since I left that country as a student. When there is a distance, there is not much involvement nor the exchange of information. Most of what I know about that subject is from few friends and through exhibitions held in Serbia. From what I have seen, there are amazing artists working in this field, a few good voices in desert which I hope will not fall into silence. It sounds a bit pessimistic but that is the reality since the current icon painting (not only in Serbia) in large part to its production can not be described in terms which we use for artistic creation. Mostly we encounter with monotone medieval fantasies, popular remixes of good evergreens with a purpose of indulging the current taste of the masses who just want something nice and cheap. Golden, “Byzantine” and so-called “canonical” seems to be the main parameters in this – as I would name it – production business, that flooded orthodox churches around the world. For many and very obvious reasons such products do not have a base to be considered a part of serious cultural discourse but I get the impression that only few really care. This comes not as a surprise since the situation in contemporary icon-painting reflects the general (poor) social and cultural picture. However, as always, there are still those who want to learn and I am looking forward to see new results.

When I was a student I cannot recall the moments that all these issues were discussed among the colleagues. When you are an artist or student of art you are mostly speaking about the lack of money and all sorts of existential difficulties. These days, when I meet with my friends, we go through all kinds of subjects among others about our artistic searches, ideas and projects.

Your compositions are unique, full of subtle and illuminating symbolism. Although they are not facile copies of old prototypes, they remain in full conformity with the truth of the sacred subject being depicted. It is clear that the freedom and flexibility found in your pictorial choices come from the way you have internalized the iconographic Tradition. What would you say has helped nurture this creative, interpretive approach to Tradition in your work?

This question brings me to the that Crucifixion from Studenica that I mentioned, which was the first icon that I took deeper into my thought. I watched it obsessively every day for hours, contemplating the forms, the composition, the colors. I was completely drawn to the calmness of Christ, the figures bellow the Cross, the entire atmosphere of the painting and I was changed by it. For me that was not just a painting but the reality beyond any comprehension. I did not want to paint like that but to grasp the essence of the image or what made the painter make such icon. This inquisitive nature came to light already in my early youth when I was scratching the paint off the furniture. Even if I know that it is made out of wood, I wanted to see it with my own eyes, to see its color and texture. My parents were going crazy but I had my satisfaction of finding the answer.

Nowadays I do not destroy the furniture but satisfy my thirst in exploring works of art and literature. By perceiving and processing the information, the ideas are accumulating with an outcome of creating a personal response on these internal processes. I make the images that are the consequence of 1) reading one or many sources and 2) internalization of the content. I wrote on purpose the “internalization of the content” as a comparison of “internalization of the Tradition” since I want to underline that before everything else I start from my own experience of the subject. What could be mutual with other iconographical ideas is that the appearance of the content is recognizable, which gives the viewer the objective ground for characterizing the work as an icon. The question of internalization and how that outcome appears out of mind is a very complex one. My opinion is that we do not have a full picture of these processes nor there is a point in a complete deconstruction of them. We can conclude is that the process is not only cognitive but also emotional and spiritual, therefore it is profound and poetic.

Can you tell us a bit about your choice of materials, especially why you prefer to work in watercolors

As much as I am concerned with the story, I seek a way to visually translate the idea. The choice of materials and technique are of the most crucial. I am in a constant search for interesting and new materials, not only in shops but also among other painters. Mostly I have a rough idea of what kind of structure and effect I want, but sometimes I buy material without any plan what to do with it, as it was the case with water colors. Before that, I have never used them but I had the wish to try them and I was fascinated by the possibilities and results. What I particularly like are the lightness, the airiness and the exposure of pigments. The mentioned qualities were very much complementing forms that I was constructing. I must mention that the image is not just a result of the colors but also paper and technique that I developed to reach the result that I wanted. Beside not using colors in a way that is perhaps expected, I also do not use the paper for watercolors because that paper holds the color on its surface. My choice was copper plate printing paper since it is able to soak a bigger amount of water which enables me to work in many layers. Beside using watercolors I am working with ink and gouache. Recently I felt that I am becoming too comfortable and repetitive with same materials. I need to learn and test more materials, so I am always trying out something new so that I might reach interesting or just new results.

The abstraction, flatness, immediacy and simplicity in your work comes across as very much indebted to some aspects of Modern art. If so, what Modern painters in particular have been influential in your development? How would you describe the affinities between Modern painting and the traditional icon? And how do you see the interaction between Tradition and contemporary artistic forms?

To come closer to the answer to the question of the relationship between contemporary artistic behavior and Tradition we will inevitably stumble over the the term “tradition”. Firstly, we could describe the term as a corpus of beliefs or practices handed over from the past generations. Logically, that brings us to the conclusion that modern art forms are also part of Tradition, because belonging to the past cultural experience, in the meantime it became an integral part of the present one. We are not only speaking here about some secular art but also about the sacred art. The interaction between traditions is actualized not only in the author’s affinities to adopt certain patterns of some traditions, but are naturally, on a deeper level integrating into cultural flow and human behavior. That is definitely the case with the Modern art and Postmodern art, since the contemporary artistic production is very much resting on older models and inventions.

What can be found in my work is a deep interest in all kinds of work of art. Since your question is about the modern influences, I would like to mention my fascination and connection with the works of Eric Gill, Bart Anthony van der Leck, Gustav Klimt, Alfons Mucha, Henri Matisse, Merab Abramishvili and Todor Mitrović. These certainly made some kind of impact on me not on a level of mere transmission of their results but on a kind of subconscious and profound level.

Your work has been described as attempting “to convey the intuition of a ‘transfigured world’ and its everlasting glow, harmony and beauty.” How important would you say is the use of abstraction in attaining this goal?

That description is the best summary of my work. Indeed, when we talk about icon, we speak of intuition of ‘transfigured world’ because we still see partially, as in a mirror. It is the attempt of reaching apophatic, always-escaping tone of the transfigured world. For the tone to vibrate in our senses, we transform the shapes to describe possible features of otherworldly. For example, in Egyptian tomb paintings the more the ruler is closer to divinity or himself becomes the deity, the more his representation is abstracted because the idea of divine is abstract and stays unknown. In Christianity we have a different situation. God did not stay indescribable and abstract for the life was made visible; we have seen it and testify to it and proclaim to you the eternal life that was with the Father and was made visible to us (1 Jn 1:2). We can and should make the images but we need to keep in mind the factor of likeness and resemblance (mīmēsis) with the archetype, so that the representation can be truthful and accessible. That is achieved on incorporating the information out of historical data or the tradition, but again all filtered trough the personal experience and understanding of the mentioned, where into play comes the abstraction as a form of conveying of intuition of what transcends our human perception.

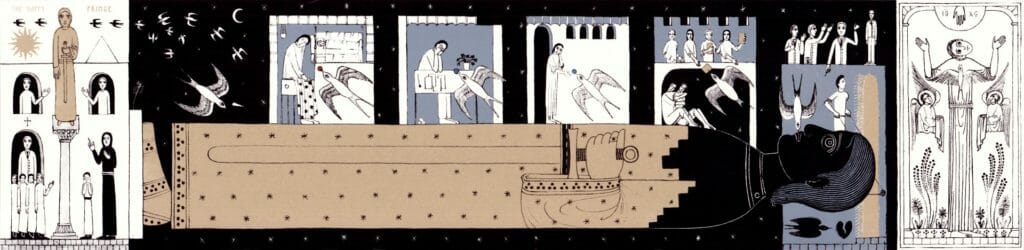

Nikola Sarić. The Happy Prince. Art print based on a fairytale by Oscar Wilde.

Full format: 80×19,5 cm; fanfold format: 10×19,5 cm. 2016.

How about the idea of caricature? Some might say your work is “cartoonish”, a trait which I do not find problematic at all in icons if used effectively. Those who disparage cartoonish tendencies need only to look at the best of Romanesque iconography to become aware that the attenuation of form, as a means of symbolic expression, is not to be mistaken for a kind of contemporary aberration. In fact, it could be said that the contemporary graphic novel or comic book are a form of manuscript illumination- vestiges of medieval art. I think your recent series of serigraph prints, The Happy Prince, based on a fairy tale by Oscar Wilde, touches on what I’m saying. So how do see this positive, expressive role of caricature in your icons?

The simplification and exaggeration of form are definitely some points that I have mutual with caricature. The subject of “cartoonish” or cartoon, as you already mentioned in the example of Romanesque art, is to be considered much more bigger than just a contemporary phenomenon. Today, cartoon and caricature is considered to have more of satirical, ironic, critical and overall political character. At these points my works departs, because I do not have such intentions nor my work does have such character. On the visual level, generally it is considered that cartoons, graphic novels and comics radiate graphical or drawing qualities, which could not be problematic or an aberration in any context. If my works are perceived to have these kind of qualities, than I am very glad about it. I could not precisely say from where these tendencies come, but it certainly has some connection with my fascination for the Art of Antiquity, the Medieval period but also Art Nouveau. My visual interpretation of “The Happy Prince“ is indeed the most graphical out of all my works but that has also to do with a fact that it is a serigraphy, so such characteristics come as a result of the technique.

Although your work first come off as very contemporary, there is also something very ancient to it…We find in it vestiges of Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek Archaic, Roman Late Antiquity, Romanesque, and Byzantine art in seamless synthesis. It seems as if you have managed to tap into the inner pictorial principles tying together the outward forms of the sacred art of all these cultures and periods, in such a way that it imbues your work with a sense of timelessness. How would you describe these universal principles of sacred art?

Though my work does have all this influences that you mentioned, I do not have a full picture in which extent they shaped the way of my expression. Although I have build on those traditions, my position and the experience of the subject is completely different from the author from the past, since I am creating in a different cultural and social environment. Perceiving from the present perspective and using the contemporary methods it necessarily makes the work as it is – contemporary. Still, there is a connecting line to the ancients, so, perhaps in a intuitive way I managed to tap on some inner pictorial principles, without knowing what those principles actually are. I feel and admire that sense of timelessness in those fine examples, but out of my small experience I have learned is that not the style is playing the biggest role into making the concrete work being so memorable and transcending – it is foremost the subject and the content of the image. That personal conclusion could bring us a bit closer into recognizing the universal principals of (sacred) art which could be comprised out of two terms – aesthetic quality and (sacred) symbolism.

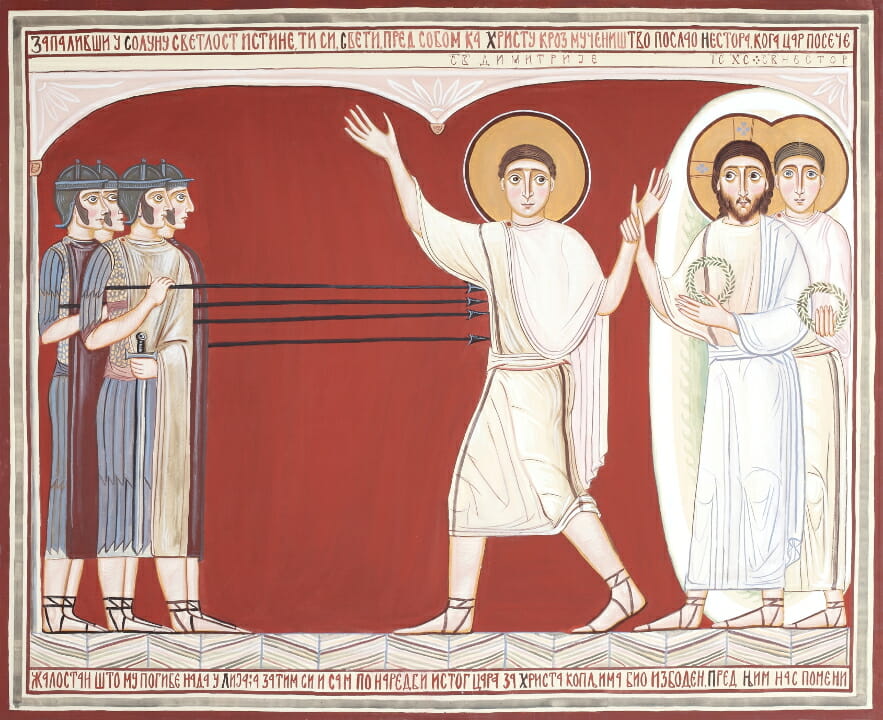

I think I first came across your work in an article that featured the icon you painted of the 21 Christian men beheaded by ISIS in Libya last year. This icon has been very well received internationally. It is a masterful and powerful composition, but it functions more as a commemoration of an unquestionably heroic act rather than as a functional liturgical image to be venerated, given that it depicts men outside the fold of Eastern Orthodoxy. Nevertheless, it is a labor of love which I’m sure has helped to bring some hope and comfort to the bereaved families of the victims and others suffering in a time of so much chaos. Has your other iconographic work been as well received in the non-liturgical artistic sphere in Germany? In other words, is your work perceived and accepted as “gallery art”? Or is it mainly treated as “church art,” albeit as a rare example of the best that can come out of a traditional religious sphere?

Foremost, thank you for recognizing my work as a labor of love. The icon of Martyrs was made spontaneously after lot of thoughts and feelings on these event. After publishing it, the image quickly went around the globe which resulted in receiving a lot of very honest feedback. Since it is adopted by many, especially by the Copts, besides being an commemorative image, in many communities and homes believers venerate the martyrs through this image by kissing, touching and praying in front of it. Though not crucial for the veneration and prayers, the Coptic Orthodox Church has them already in their Synaxarium. Since you tackled the question of the use of the image, I feel the need to say that I did not made this pictures (or any other non-commisioned image) with an aim to find its place in a specific or enclosed circle. I do not paint only for Christians nor for galleries since the art and even more Christian art is for everyone. It is so, because it is not because of the general public that they are being made, but it is so that they are made and eventually being presented (or not) to the public. That does indeed opens a crucial question – for whom or why do I make these paintings. The answer may be somewhere on a scale between the own will to create and what Paul says that God is the one who, for his good purpose, works in you both to desire and to work (Phil 2:13). Being present and open to the public, people interpret and use them in a way they can or want. Both Christians and non-Christians, view them from or put them in different kind of perspectives, from “icons” to “sacred art”. Astonishingly the works are generally very well received in a non-liturgical and even in a non-Christian circles, even though the content of the images is clearly Christian. Skipping all of the intellectual categorizations, what really interests me or what drives me is when the individuals share their deep personal experience. As much as I am happy that some Christians use the image for veneration I feel blessed when a person describing himself as an atheist or agnostic says to me that an image changed him or means something to them. What could be also seen as extremely positive is that, when I apply for a prize or a group exhibition, when it comes to my work there will be likely a strong debate among artists, gallerists, curators and art critics if my works should have a place in a contemporary art show. Not the aesthetic quality of work but the religious character and clear Christian content seems to be a bone in a throat of many. This discriminatory phenomenon is very paradoxical in a so-called democratic society and so-called pluralistic culture, but it is not all so negative since there are some with a clear head. Such hot-cold situation in my case comes as very good and healthy since there is reexamination of the past, present and most importantly the future of cultural discourse and that is for me one of signs that I am on the right way.

You also run Wallsuit, an interior design studio in Hanover, where you now live. How did you come to live in Germany? And how does your design work relate to your iconography?

The idea of Wallsuit is something that I did till 2014 when I returned to painting. For few years I was working in a field of design of wall surfaces which was my interest at the time. It was a very nice story with great results, but now I left it behind me since I am very fulfilled with what I am doing right now. That started about the same time when I came to Germany where I met my partner, with whom I eventually got married. That is how I stayed here.

I am not completely sure how does the design work relate to my paintings but on a visual level I think there are some common points and references.

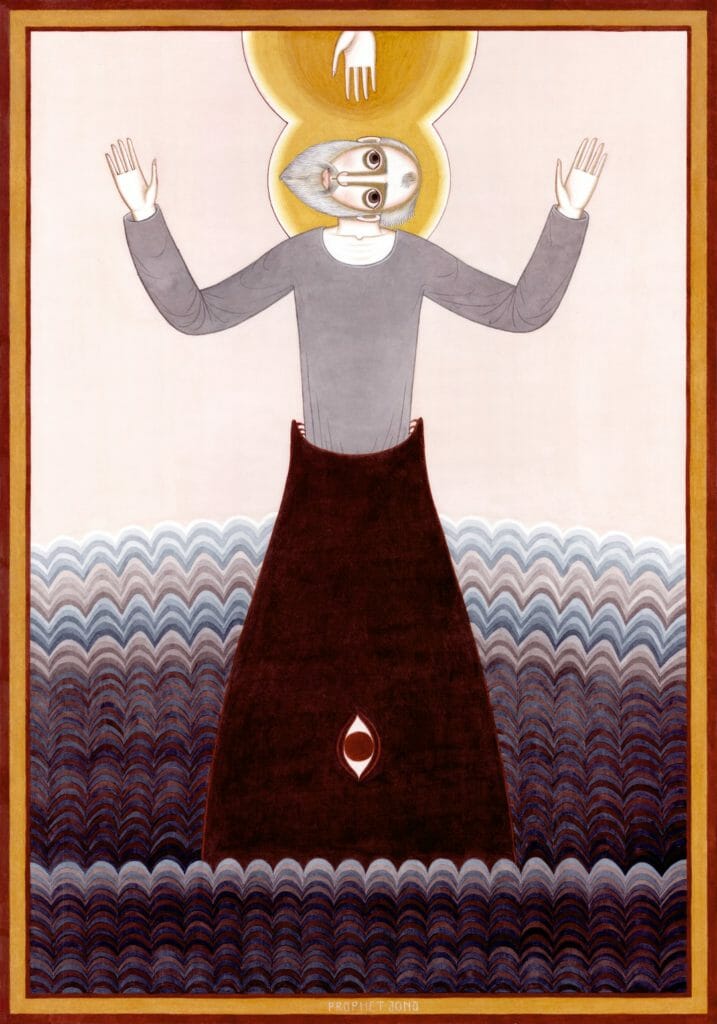

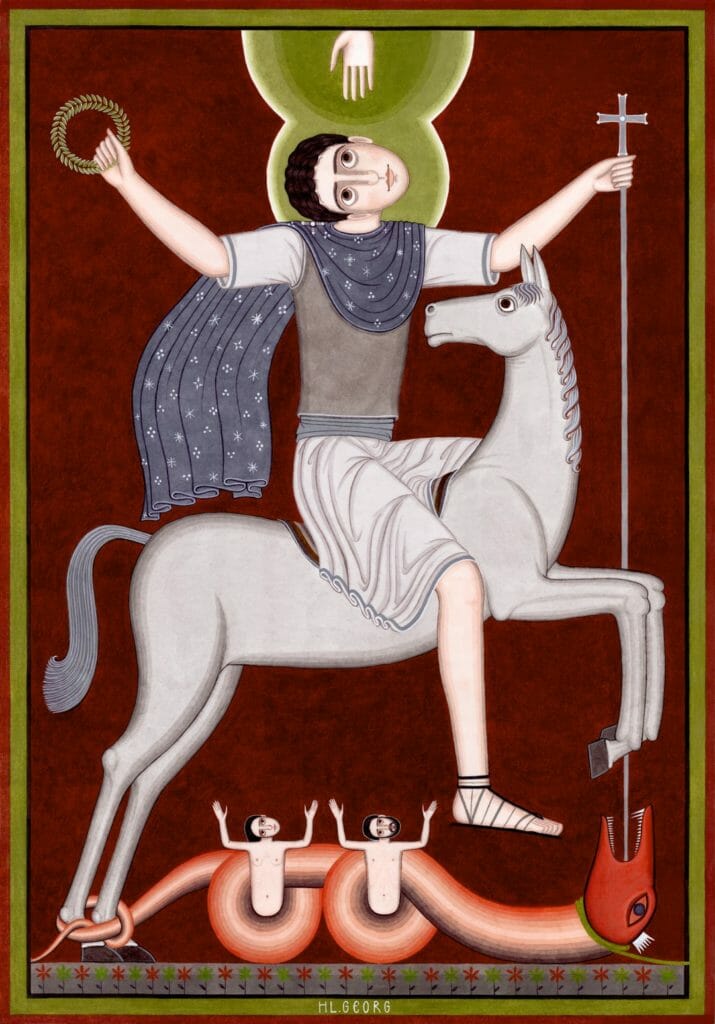

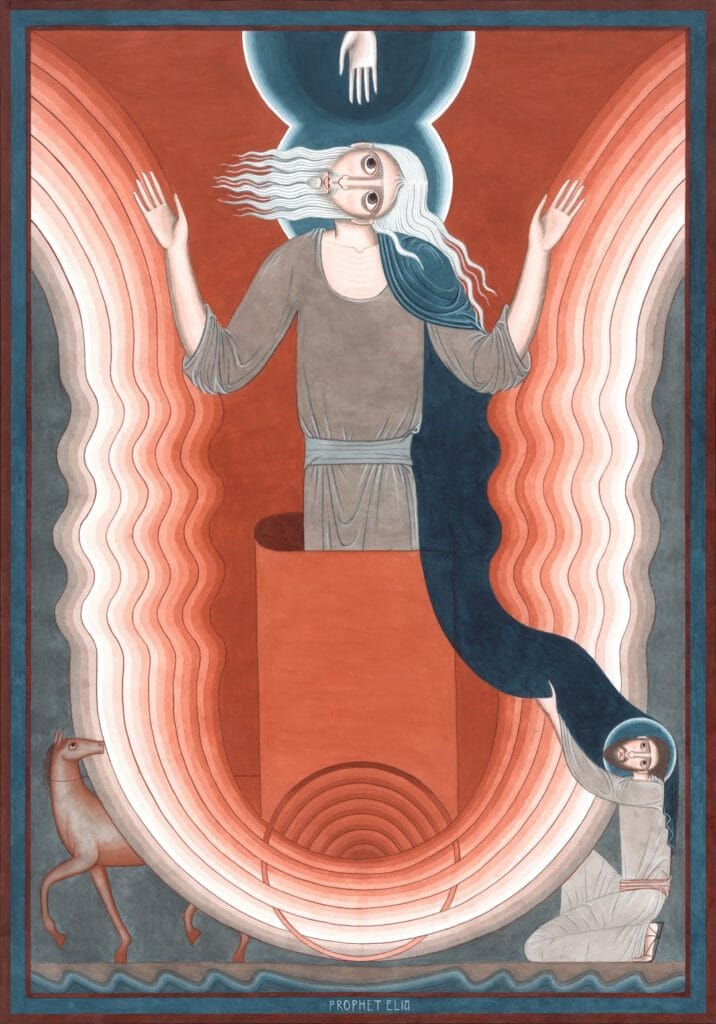

You tend to work in series, groups of icons tied together by a common theme, such as your interpretation of the Lord’s Parables. Do you have any series planned for the near future?

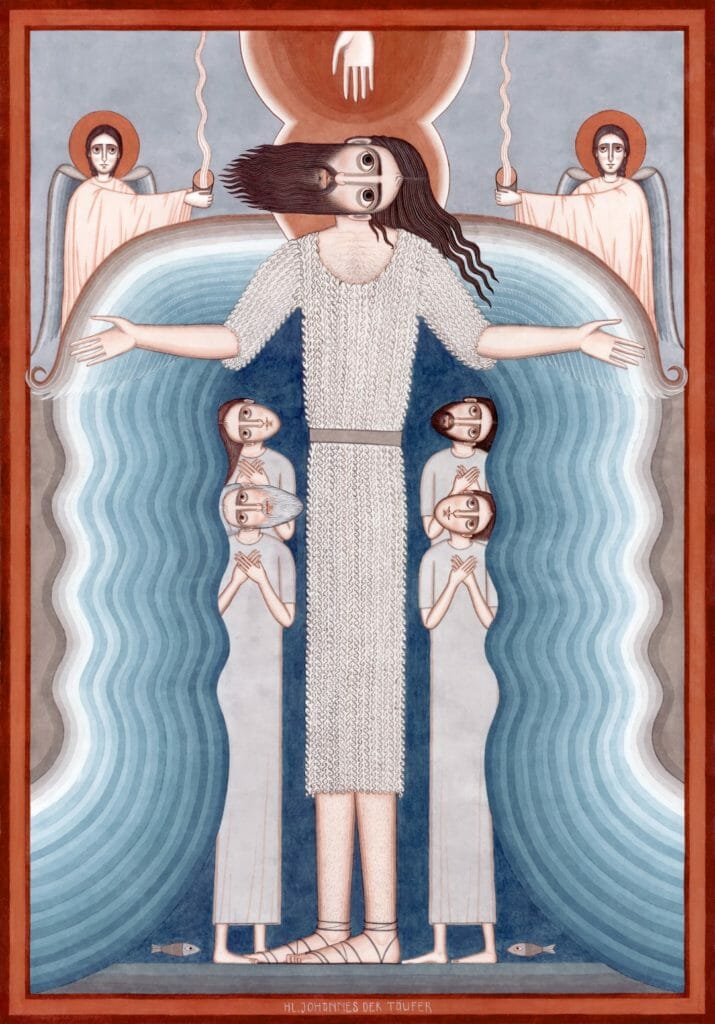

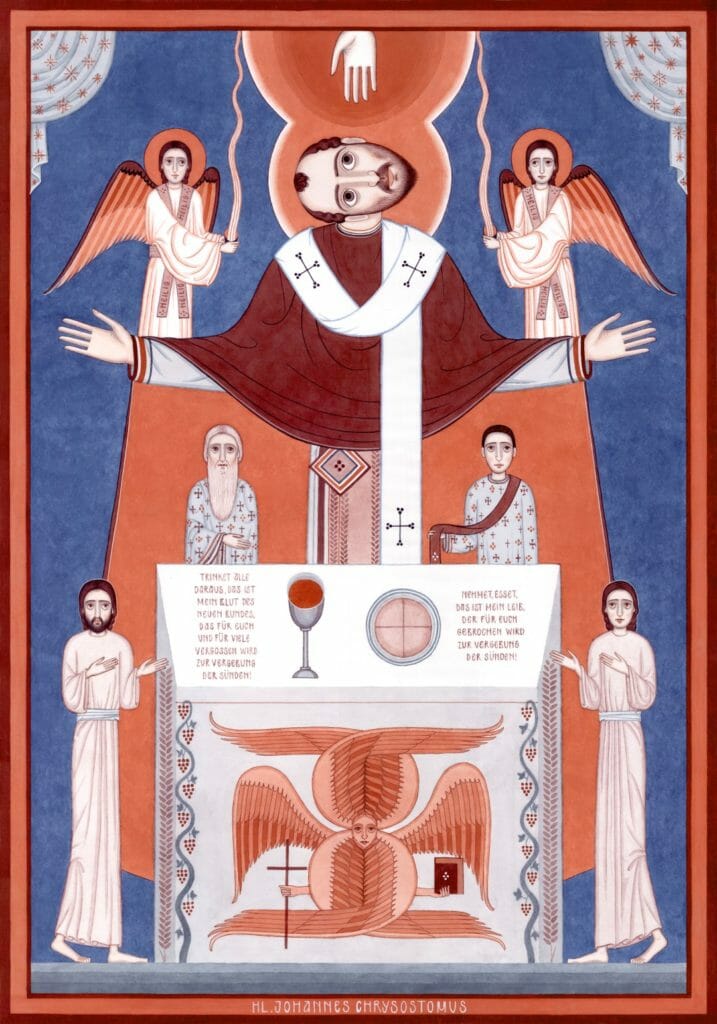

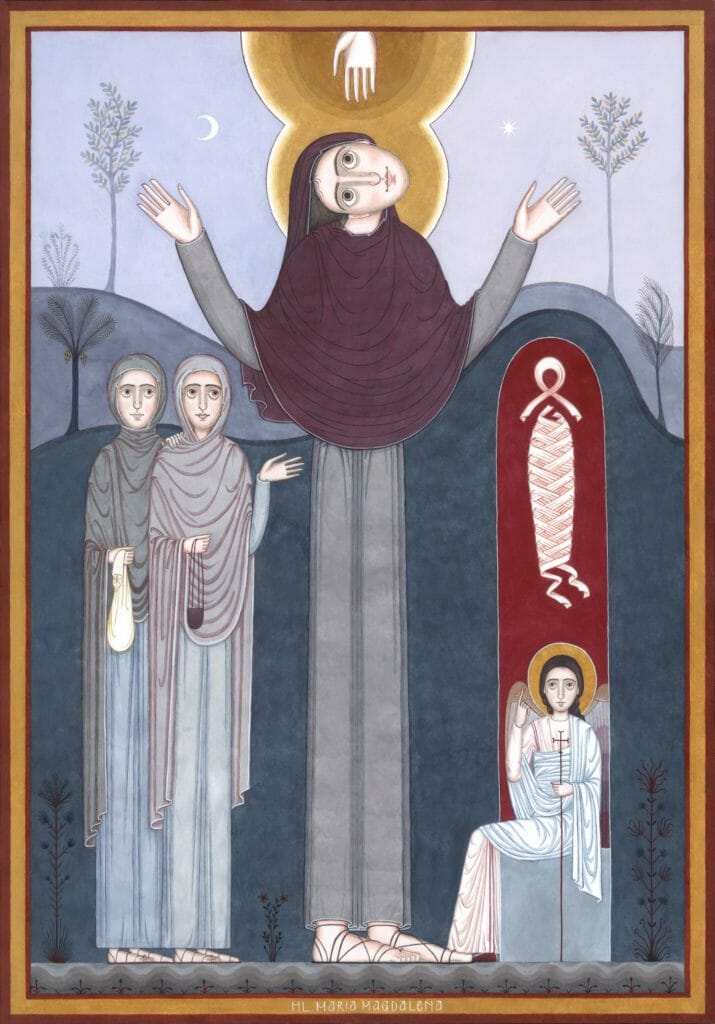

Yes, I do mostly work in cycles, primarily because I tend to build a story on a certain subject. Some ideas and thoughts just stay in my mind and with time and work they expand into a bigger frame. Besides Lord’s Parables, there is also the cycle of “Witnesses” where the series developed completely spontaneously after painting “Laocoön”.

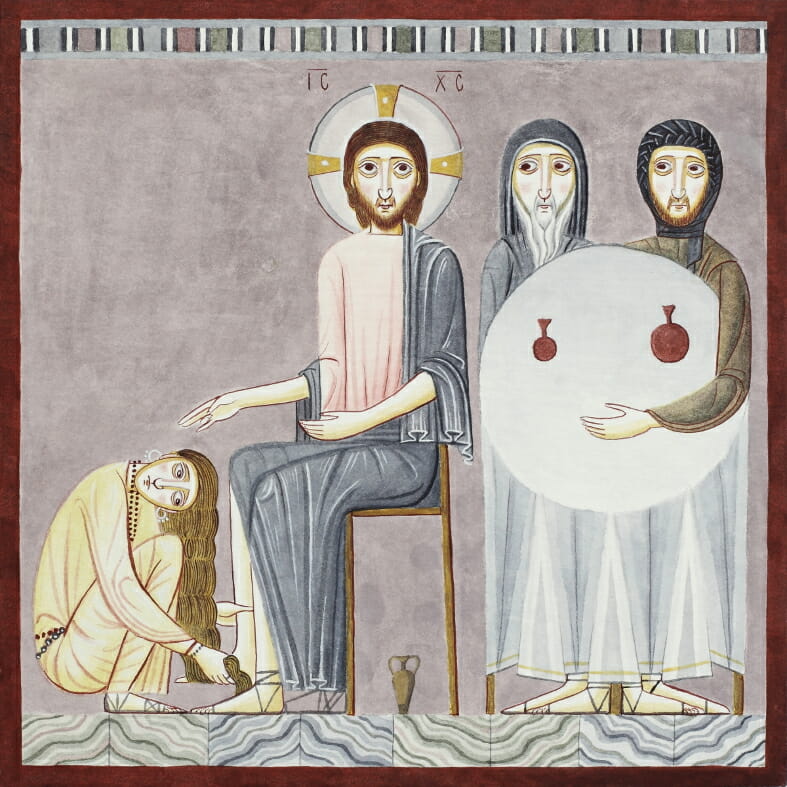

Recently I am working on a series that I named “Cycle of Life”. The title and idea came to my mind after painting The Crucifixion and and after some thoughts on Munch’s 1902 exhibition in Berlin which he entitled “Frieze of Life – A Poem about Life, Love and Death”. Through his painting series, Munch is self-examining his life and the existential questions. I was projecting the same thoughts on Christ, working on these terms through the christological narrative. I am contemplating on his life through his words and deeds, going through biblical exegesis as a process of building the story, sporadically throwing the light on certain biblical occurrences or personal thoughts that could bring some new moments in perceiving the life, death and above all the love of God.

As a way of closing our discussion, what would you recommend to iconographers aspiring to engage more creatively with our living Tradition?

My recommendation would be to engage in sensible dialogue, in thinking and learning processes, to be perceptive and be hard working. Do not float in shallows but take a risk and swim into deeper waters.

Thank you very much Nikola for taking the time to share your experience and insightful comments with us.

Readers can see more works from Nikola on his website: http://www.nikolasaric.de/homepage/?lang=en

A great exploration of creativity and soul through an in depth interview of a very intellectual and thought provoking artist.

I find the work shared in this article fascinating and compelling, and if I were to have such images in my home I would be blessed by their power and spiritual significance. I would however like to point out and comment upon one pictorial technique that while I find it extremely effective and expressive, carries with it a different functional implication than depictions typically found in iconography, namely, that of turning a depicted saint’s head 90 degrees.

Clearly the effect of this gesture is to indicate the saint’s connection with heaven, either via martyrdom (which I think is the best use) or via prophetic ecstasy (which I think is a more problematic use). The question arises in Christian religious art of different confessions, how do we depict the saint as a person living in the kingdom of heaven? In my understanding, the Orthodox answer to that has been for the most part to depict the saint as finding heaven in and through the created world, so their gaze and body language is still usually directed on the horizontal (social) plane, whereas other traditions have expressed saint finding heaven above/outside/beyond this world, and this is generally indicated by the saint’s body language of detachment: either looking up at the sky, or looking down passively with their eyes nearly closed. In other words, disconnected from the horizontal social plane.

I am not challenging the appropriateness of this technique in the realm of sacred art. I am however trying to indicate that if other iconographers wish to experiment with such a gesture, I believe you will find that the result is a depiction of a saint who is not entirely present in the room with you, thus weakening the second essential aspect of all icons – the communion of the saints. The first essential aspect of all icons is in my opinion still intact in the images shown in this article, namely, the holiness of matter as effected through the incarnation and shown in the transfiguration.

with your prayers,

baker

I mostly agree with you Baker, but it is important to recognize that not all iconography, even in the Eastern tradition, appears to have liturgical communion with the saints as its primary purpose. Historically, we see plenty of icons which are more illustrative in character, where the narrative of the event is most visually prominent, and the purpose of the icon appears more about preserving a historical memory, rather than praying to someone.

So I think that in the special case of an icon of some extraordinary historical event, like the vision of St. Paul, it is reasonable for the temporal narrative of the event to dominate the image. But I would say that such an icon is always an outlier. It’s not the ‘main’ icon of St. Paul – not the one you would put on an iconostasis.

So that being said, I think you are right to be concerned at the frequency with which we are seeing this gesture used in contemporary iconography. If it were to become normative or central, then our iconography would indeed move a step closer to western religious painting, and a step away from its central liturgical role.

Thank you Mr. Galloway and Mr. Gould on your thoughtful comments on this interesting subject. In my work there was no intention in making an image for liturgical use nor addressing all aspects of icons. I could roughly describe it as a series of attempts to develop a visual content that is dealing with certain ideas, stories and characters of my personal interest. In the Witnesses cycle I was working on the subject of being a witness in a biblical use of the term and in which way these different characters through their lives and deeds were witnessing God. For me, if the saints did not turned their head (attention, focus) in this illogical and strange position to meet the Lord than it would not work. Though being largely influenced by the iconographical Tradition as well as being established on theological and biblical sources, as you can see, these artistic searches are filtered through the strainer of my own intuition and experience of the subject. They are subjective reflections, in which there is no intention to set an iconographical standard or to be liturgically appropriate, therefore they should not be taken as model in any context. At the end I would like to share a beautiful thought by theologian Dr. Fousteris in his text for my exhibition in the Mount Athos Center which is also a partial revelation of my intentions and interests: “Death and hope, love and wrath, solitude and passion, falsehood and faith, humility and hypocrisy in their real dimensions and intensity. It does not flatter the beholder, nor does it attempt to teach him or her. Its only concern is the truth of things.” You can read the entire text here: http://kurz.nu/r/dlm

The role and significance of my work (in liturgical, cultural or any other frame) I would leave to you and others to find. I am glad that I had a chance to make them and to see that they have some meaning in someones else’s life.