Similar Posts

This is the 4th and last post in the series “Imagination, Expression, Icon: Reclaiming the Internal Prototype”: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

When you make an icon, do not copy it exactly…

-Elder Sophrony[i]

Now that we’ve clearly defined the terms nous, techne, Tradition, imagination and expression, we’re in a better position to bring it all together in this final post of our series.* However, for some there might still remain fear and doubt, thinking that we’re just attempting to promote “artistic license” in icon painting. But not to worry, we’re not advancing incautious and unrestrained subjectivism, a blurring of the edges between iconography and gallery art. Ironically, it seems to me as if the 20th century revival of the icon has instilled in some of us the notion that Tradition is the ossification of artistic form, rather than reawaking in us an awareness of its living, ever-renewing power. Safeguarding the iconographic “canon”[ii] has led to a morbid fear of innovation making it difficult to access Tradition today in a fresh and authentic way.

So we are warned, “Imitate don’t innovate.” While others say, as mentioned earlier, “Icons are not art, but rather vehicles of prayer.”[iii] Nevertheless, although true at face value, these rhetorical tropes in fact bear the seed of misunderstanding. Perhaps they can be seen as partly caused by an oversimplification of the thought of the pioneers of the icon revival, who in their polemics aimed at rightly delivering the traditional icon from the dominance of Western naturalistic painting within the Church, disparaged art since the Renaissance as distorted products of the impassioned imagination. Consequently, Tradition became equated by some with rigidity, a return to the past and the inalterability of a monolithic “Byzantine style;” while the imagination became its opponent, the cause of unceasing fragmentation and innovation fueled by individualism. This narrative, in which the imagination becomes a major if not the main culprit, has overshadowed the more nuanced areas of the pioneer’s thought surrounding the creative act of icon painting.[iv]

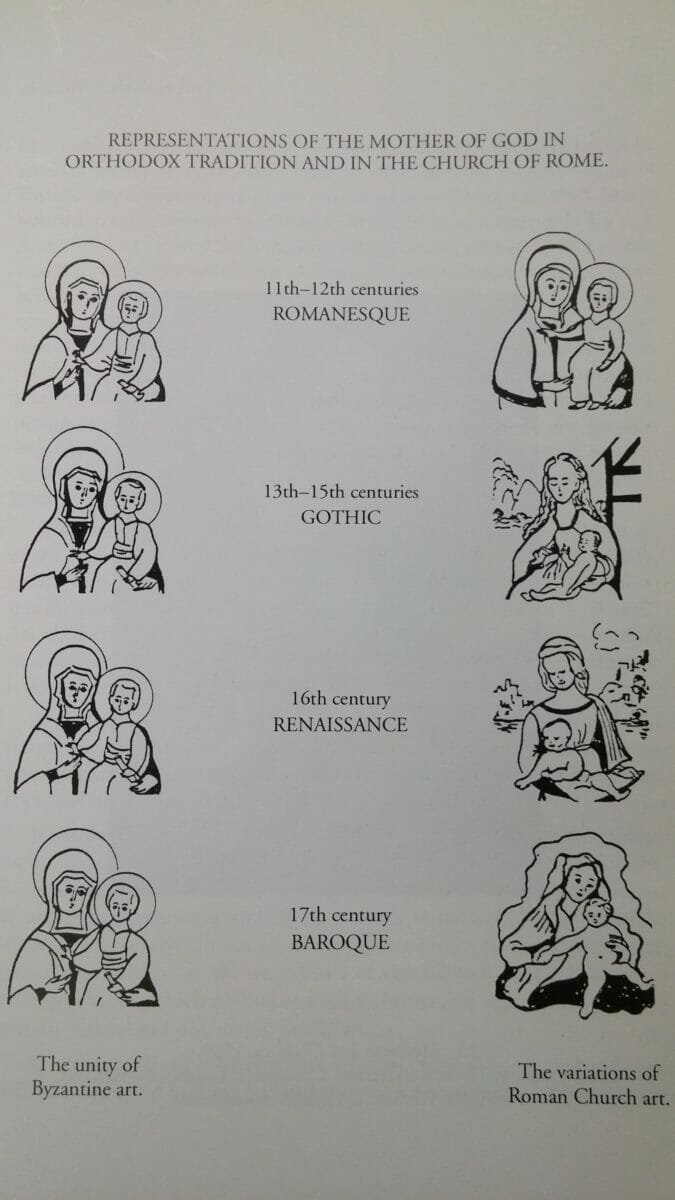

A case in point, which illustrates this simplistic notion of Tradition, can be found in Michael Quenot’s book, The Icon: Window on the Kingdom. There we find a classic comparison attempting to emphatically show the differences between the Orthodox icon and Western religious painting. It consists of a chart with two symmetrical vertical columns, which Quenot admits, “lacks nuance.”[v] On the left hand side column he gives us an illustration of the Theotokos, going from top to bottom, that never changes from the 11th to the 17th centuries; but on the right hand side we find an Italianate image of the Madonna changing drastically from century to century. The column on the left overemphasizes, not so much the plenitude of unity, as forced and lacking uniformity at the expense of diversity; while the right hand disparity, drastic variation, or rather, fragmentation, is shown as the flaw of humanistic art. What we have here is an overstatement that undermines the irrefutable fact of the stylistic diversity that has always existed in Orthodox iconography, and therefore only ends up distorting our understanding of the icon. To put it another way, it could be said that this illustration rhetorically tells us, “The icon never changes because it is not art.”

Be that as it may, as we have said, this kind of statement instead of safeguarding the icon ends up undermining and stifling its creative import and fresh possibilities. It leads to the assumption that, since it is not the “fine art” of an ivory tower individualist, anyone can paint an icon, there is no need for previous artistic training or knowledge of pictorial principles. All that is needed is a pious disposition. But, is this not in fact a denial of the icon as techne? In an attempt to liberate the icon from the clutches of the imagination we unwittingly end up shackling it by lowering the standards of its craftsmanship. The specter of “fine art” in the end wins, since we have not replaced it with an accurate understanding of the traditional, or normal, doctrine of art, in which the imagination plays an efficacious role. What we rather should be stressing, as stated earlier, is that the icon is in fact a clear example of the realization of the highest capacity of art, demanding of us the highest levels of knowledge, skill, creativity, ascetic discipline and spiritual vision. Both, noetic intuition and artistic ability are necessary. As Aidan Hart puts it:

But where does the mean lie between unspiritual innovation on the one hand and mere duplication on the other? Genuine variety in liturgical art occurs when the iconographer unites spiritual vision with artistic ability – energized with courage and the blessing of God. Vision without artistic ability produces pious daubs. Not every saint can paint icons. Although icons are more than art, but they are not less than art.[vi]

All of this confusion is one of the negative symptoms of today’s rampant popularity of the icon. In an attempt to indiscriminately make it accessible to the masses we unwittingly end up promulgating mediocrity, imitation and mechanical copying, wherein the iconographer is expected to suppress his intellectual, creative and interpretative engagement. The human component is undermined. With this attitude it matters little whether the icon is hand-painted or mechanically reproduced by thousands into slick and glittery kitsch. In the end depersonalization, the iconographer as a numerical “unit” of industry, interchangeable with any other “unit” as a cog in a machine, replaces his qualitative presence as an author in collaboration with the Holy Spirit.

Thus, ironically, the icon, a witness to the regeneration of the hypostatic principle in man, the saints as unique persons[vii] – who have actualized their deification in a particularized and unrepeatable manner[viii] – becomes a mechanistic exercise that stifles the iconographer’s unique mode of expression. But, as Elder Sophrony clearly states, years after he had abandoned his career as a secular painter in pursuit of the hesychastic life: “When you make an icon, do not copy it exactly. Not because you will not be able to do it as well as the original, but because it has already been done, it already exists in history – one should not repeat.”[ix]

In other words, the icon painter should not repeat the result of encounter, but rather his work should arise and re-present (ex-press) a true, fresh and living re-encounter with the subject depicted. But, this, of course, is not to promulgate the modernist cult of individualism or so called “artistic genius.” On the contrary, as just mentioned, life in the Body of Christ presupposes the flourishing of ourselves as unique and true persons[x] in loving communion with one another, in contradistinction to our ego-centric or individualistic identity in which we wither as isolated numerical “units.”[xi] Moreover, let us not forget that in this ecclesial life, “there are diversities of gifts, but the same Spirit.”[xii] That is, inner union in the Spirit does not mean uniformity at the expense of diversity. Each person as a member, in a unique manner, contributes towards the edification of the whole Body. Therefore, the traditional practice of “anonymity,” that is, of not signing the icon, should not be understood as an aspiration towards the complete obliteration of the iconographer’s gifts and creative temperament.[xiii] It is rather a reminder that only in humble cooperation with the Divine Craftsman, in becoming one with Him through the Holy Spirit, will his true self and art flourish to the fullness of their capacity. Obedience becomes liberation. Thereby he will be able to uncover nuances contained in the prototypes previously unnoticed and contribute unrepeatable expressions of Tradition. In undermining this side of the icon, seeking to protect it from “artistic license” and foreign cultural influences, we may in fact blunt its power, making of it a purely mechanical act that contradicts basic principles of Orthodoxy.

How then is the iconographer to avoid the mistake of taking freedom for license? Only when he has made the Tradition his lifeblood and experienced it from within, as ever-renewing power in the Holy Spirit, as accessible today as it ever has been in the past. For it is, “the same yesterday and today and forever.”[xiv] Only when he has begun to discern and made the timeless principles of the icon his own. But, how is he to avoid arbitrary innovations? Not by fear and hesitation, but only be taking risks. Only when he has, as we have said, encountered the prototypes, not as sketches observed external to himself, but as the heavenly realities or saints he is communing with, in the chamber of his heart, apprehending with his noetic eyes. Only when the logos, the meaning or “dogmatic content which has determined [the] composition”[xv] of the subject is known from the inside out, in such a way that it touches him, imprints him with its unique presence, and begins to guide the creative act. For it is “the business of this art not only to ‘teach,’ but also to ‘move, in order to convince’: and no eloquence can move unless the speaker himself has been moved.”[xvi] This is what we mean by interpreting and re-imagining according to Truth and ecclesial reality, rather than fantasy. In other words, as Philip Sherrard explains, speaking of the creative act in icon painting:

…There is here no distinction between art and contemplation. The artist must raise his vision from earthly to divine concerns and perceptions until he can mentally entertain the form which he is to imitate – until this form lives within him with its own inherent vitality. There has to be an endless renewal and repetition of the internal imaginative act, an endless recreation within the life of the artist of the spiritual realities which are the subject of his work and which must spontaneously inform his work if it is to live.[xvii]

Although forgotten, this is in fact nothing new, but in full accord with the method followed by medieval craftsmen, whether from the West or the East. As Titus Burkhardt describes in his essay, The Decadence and Renewal of Christian Art, the craftsman, in working from consecrated models or prototypes, never went about it “mechanically,” but rather always interpreted them through a process of “identification,” what we have referred to as an “encounter” of living communion with the subject. Burkhardt also suggests that this method is indispensable for us today if we are to renew Christian sacred art:

More particularly in the Middle Ages, every painter or sculptor was in the first place a craftsman who copied consecrated models; it is precisely because he identified himself with those models, and to the extent that his identification was related to their essence, that his own art was “living.” The copy was evidently not a mechanical one; it passed through the filter of memory and was adapted to material circumstances; in the same way, if today one were to copy ancient Christian models, the very choice of those models, their transposition into a particular technique and the stripping from them of accessories would in itself be an art. One would have to condense whatever might appear to be essential elements in several analogous models, and to eliminate any features attributed to the incompetence of a craftsman or to his adaptation of a superficial and injurious routine. The authenticity of his new art, its intrinsic vitality, would owe nothing to the subjective “originality” of its formulation, and everything to the objectivity or intelligence with which the essence of the model has been grasped. The success of any such enterprise is dependent above all on intuitive wisdom; as for originality, charm, freshness, they will come of their own accord.[xviii]

It is important to emphasize how Burkhardt singles out how authenticity, vitality and success are not to be attributed to mere subjectivism, but rather depend on “objectivity or intelligence,” and “intuitive wisdom,” which pertain to nothing other than noetic intuition, as we have described. In such a process, although the iconographer will not seek “self-expression” for its own sake, his creative temperament will not be quenched, but it will be rather given freedom in the Spirit, for “where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.”[xix] And, “This is inevitable only because nothing can be known or done except in accordance with the mode of the knower. So the man himself, as he is in himself, appears in the style and handling, and can be recognized accordingly.”[xx] Only when we paint from our experience and knowledge, arising from living communion with the subject depicted – rather than from the experience of others, whether they be from the 14th, 15th or earlier centuries – will our icons be full of vitality and authenticity, living expressions of living Tradition.

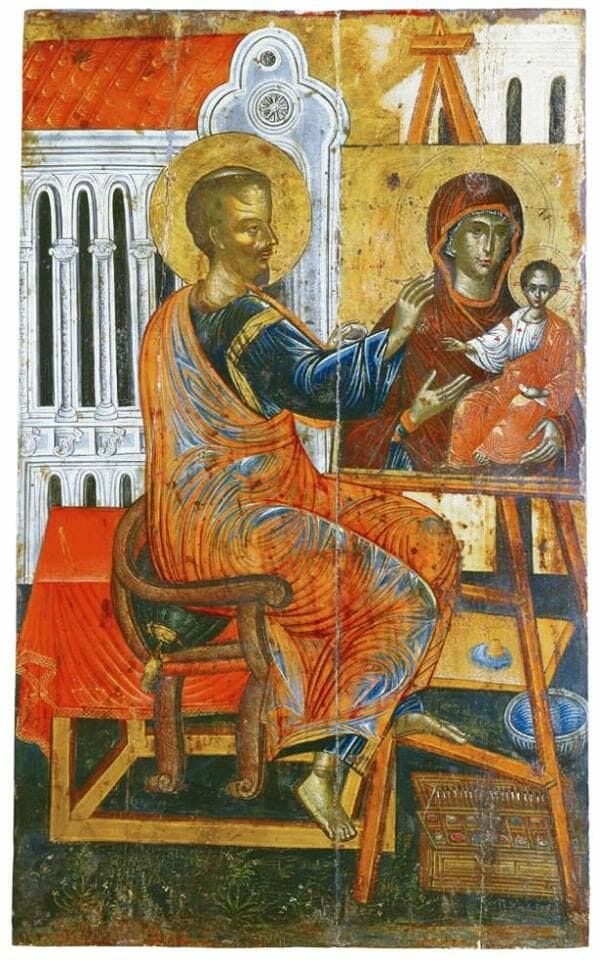

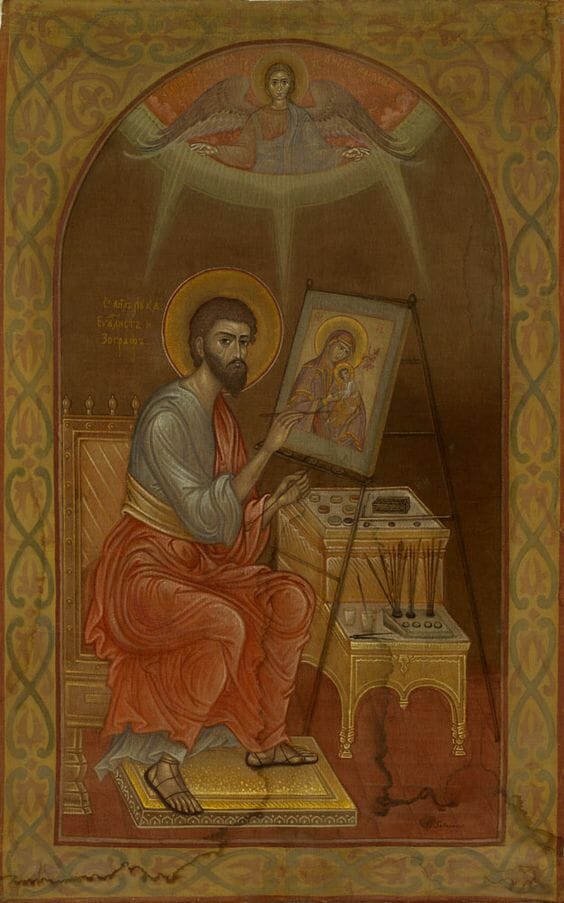

The Evangelist Luke paints the icon of Virgin Date. Early 17th century. 91.8 x 56 cm. At the Byzantine and Christian Museum of Athens.

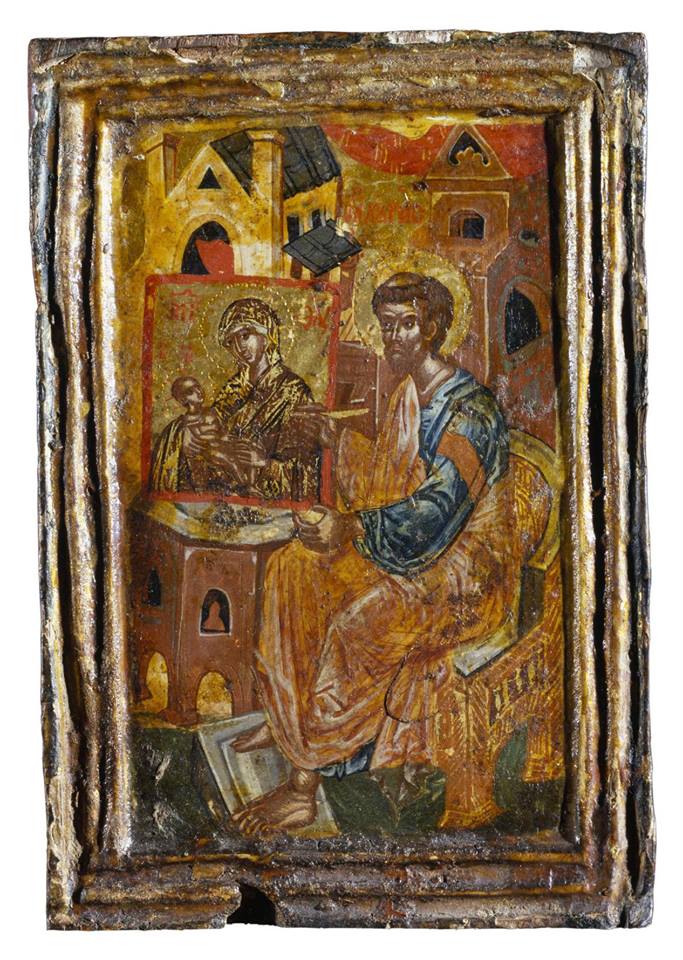

A young iconographer paints his icon of the Transfiguration overshadowed by the presence of St. Luke the Evangelist, patron of icon painters. Contemporary icon by Helena Murariu.

Hence, expression will not be so much the vain exhibitionism of individualistic idiosyncrasies, as the articulation of what needs to be said, arising from and in conformity with the inner meaning of the subject of the work at hand. Keeping this in mind, let us also remember that no two homilies are identical in expression, whether it be from the mouth of a St. Gregory of Nyssa or St. Basil, although they proclaim the same Truth. So, “The orator whose sermon is not the expression of a private opinion or philosophy, but the exposition of a traditional doctrine, is speaking with perfect freedom, and originality; the doctrine is his, not as having invented it, but by conformation (adaequatio rei et intellectus).”[xxi] It is the same with the rich variety of expressions seen in icon painting. The iconographer preaches the Gospel in colors and chants hymns of praise, trembling as he says, in the words of the Nativity sticheron, “How hard it is to compose hymns of love, framed in harmony.” With his art he paints the Word, plastically manifesting, indeed enfleshing the Logos. This is truly an “artistic license” of kerygmatic expression in free will. For as Christ Himself has ordained: “Go into all the world and preach the Gospel to every creature.”[xxii]

Conclusion

To conclude, let us summarize the basic principles of the iconographer’s creative act, what we mean by freedom, imagination and expression. The creative act is “free” in so far as it is directed by the purified and illumined nous which is imbued with and partakes of the inner life of Tradition. Techne, skill, or art, remains in the craftsman, as it is a “science,” a form of knowledge, residing in him. With his art he physically shapes and moulds matter, this is the “servile” act. The “free” and “servile” functions coincide, “the former consisting in the conception of some idea in an imitable form, the latter in the imitation (mimesis) of the invisible model (paradeigma) in some material, which is thus in-formed.”[xxiii] Hence, the object itself is not the art; it is rather the artefact. The one pertains to the nous, the other to manufacture, respectively. The intermediary between the two is the faculty of imagination, which should not be equated with mere fantasy. Rather, this faculty, guided by the nous, takes in sense impressions and combines them with images from the memory, arriving at pictorial solutions through a process of mental synthesis.

Therefore, as A. K. Coomaraswamy says, echoing Kontoglou, pertaining to traditional craftsmanship, “The artist’s theoretical or imaginative act is said to be ‘free’ because it is not assumed or admitted that he is blindly copying any model extrinsic to himself, but expressing himself, even in adhering to a prescription or responding to requirements that may remain essentially the same for millennia.”[xxiv] If these distinctions are kept in mind, there is no need to fear the imagination, expression, or so-called “artistic license,” in the homiletics of icon painting. For we have been given a Spirit of freedom not of bondage[xxv], as we partake of our ever-renewing and living Tradition.

Notes:

*For a shorter version of this part of our series see “On the Gift of Art…Part IV: Challenges After the Clash,” in: Orthodox Arts Journal, January 5, 2015, https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/gift-art-part-iv-challenges-clash/ (accessed 17 January 2017).

[i] As quoted in: Sister Gabriela, Seeking Perfection in the World of Art: The Artistic Path of Father Sophrony, Essex, Stavropegic Monastery of St. John the Baptist, 2014, pp. 158- 159.

[ii] In clarifying how to approach the notion of “canon,” Emilie Van Taack, the French iconographer, teacher, and student of L. Ouspensky notes: “Generally, it is said that an icon must follow very strict canonical rules, but this is not true. There is only one rule, Rule 82, decreed by the Council in Trullo, part of the Sixth Ecumenical Council.[…]What is stated is that an icon must show both the humility of the Man Jesus and His glory as God; that is, it must manifest the Incarnation…We have to learn from the old, but we do not have to copy the old exactly…In defining what is “canonical” in icon painting, we have, of course, many beautiful old canonical icons to refer to. But canonicity is difficult to define. I cannot tell you what is canonical, because the icons themselves define the canons. It is a circle, and we must accept it like this. By looking at these beautiful icons, studying them, copying them, little by little they help you to see in yourself this image of Christ, and then you will be able to paint it without looking to the old, because you will have it in your heart.” E. V. Taack interview, “Perspective and Grace: Painting the Likeness of Christ,” in: Road to Emmaus, Vol. VII, No.2 (#25), Spring, 2006, pp. 40- 41. http://www.roadtoemmaus.net/back_issue_articles/RTE_25/PERSPECTIVE_AND_GRACE.pdf (accessed 23 November 2016); Similarly, Irina Yazykova writes, “The canon, rather than depriving the icon painter of freedom, more accurately holds up an ideal and a goal. The canon orients the icon toward a prototype. Properly understood, a prototype is more than just a pattern to copy: for the faithful, it represents something approximating the ‘true likeness’ of embodied holiness. Reference to a prototype helps prevent iconographers from losing their way.” I. Yazykova, Hidden and Triumphant: The Underground Struggle to Save Russian Iconography, trans. P. Grenier, Paraclete Press, Brewster, 2010, p. 10.

[iii] “Restricting the icon to mere object art would deprive it of its principal role.” M. Quenot, The Icon: Window on the Kingdom, SVS Press, Crestwood, 1991, p. 12; “The icon is not a form of visual art and aesthetic art as such; it is, primarily an expression of the theological experience of the Church, and a statement of it.” D. J. Sahas, Icon and Logos: Sources in Eighth- Century Iconoclasm, University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1986, p. 5.

[iv] This is why we began this paper with a quotation by P. Kontoglou, since many are unaware of the nuances of his thought regarding authenticity of expression in iconography. In clarifying L. Ouspensky’s views on the same topic his student E. V. Taack notes: “Yes, we now have many icons, which are simply reproductions of old icons. Uspensky insisted very strongly that we are not to copy, but this fact can also be misunderstood, we have absolutely no reason to reproduce an old icon, because this means that we have no life in ourselves. What we want to do is not to reproduce an icon outside ourselves; we have to take it inside and re-give it. Even if we copy, we have to have this process. If we are living in a spiritual way, it will not be just a copy, it will be a living copy.” E. V. Taack, op. cit., pp. 57-58.

[v] M. Quenot, op. cit., pp. 74- 75.

[vi] Aidan Hart, “Diversity Within Iconography: An Artistic Pentecost,” in: New Liturgical Movement: Sacred Liturgy & Liturgical Arts, 24 July, 1211, http://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2011/07/aidan-hart-on-diversity-within.html (accessed 23 November 2016).

[vii] Archimandrite Zacharias, Man the Target of God, Mount Tabor Publishing, Dalton, 2015, p. 133.

[viii] As Archimandrite Zacharias says, “…we know that man’s hypostatic spirit will not dissolve into the supra-personal absolute, like a drop in the ocean or like breath dissolves in the air, but it will preserve its particularity and uniqueness for all eternity.” Ibid., p. 125.

[ix] As quoted in: Sister Gabriela, op. cit., pp. 158- 159.

[x] Archimandrite Zacharias, op. cit., p. 251; Cf. idem, The Hidden Man of the Heart, Essex, Stavropegic Monastery of St. John the Baptist, 2007, pp. 11-12.

[xi] On the distinction between individuals and persons as quantitative and qualitative categories respectively, see: P. Sherrard, Church, Papacy and Schism: A Theological Inquiry, Denise Harvey (Publisher), Evia, 1996, p.26.

[xii] I Cor. 12: 4; Cf., Archimandrite Zacharias, Christ, Our Way and Our Life: A Presentation of the Theology of Archimandrite Sophrony, South Caanan, St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press, 2003, pp. 40- 41.

[xiii] On the “transformative” or “resurrectional” aspect of anonymity in traditional craftsmanship see: R. Guénon, “The Two-Fold Significance of Anonymity,” in: The Reign of Quantity & The Signs of the Times, Sophia Perennis et Universalis, Ghent, 1995, pp. 80- 81. However, his thought on this matter stands only if interpreted through an Orthodox metaphysic. For although he stresses that the overcoming of the ego is not to be confused with the notion of “extinction,” his understanding of “individuality” (“ego”) as compared to “personality” should not be confused with the Orthodox doctrine of the human hypostasis and theosis. Following the Vedanta, he sees the attainment of “self-realization” for the human individual as the overcoming of illusion and the multiplicity of manifestation by returning to the unity of the first Principle, that is Ātman (Self or Universal Spirit), which was in fact the individuals true Self or “Divine Personality” all along, since all living beings are ultimately identical in their essence with it. In other words, what we have in this “Supreme Identity,” as Islamic esoterism would put it, is the total collapse of the created and Uncreated into one Absolute Reality. Therefore, as P. Sherrard has noted, Guénon’s metaphysics, “involves a total denial of the ultimate value and reality of the personal. It demands as a condition of metaphysical knowledge a total impersonalism – the annulment and alienation of the person.” See: P. Sherrard, “Christianity and the Metaphysics of Logic,” in: Christianity: Lineaments of a Sacred Tradition, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, Brookline, 1998, p. 108; R. Guénon, “Fundamental Distinction between the ‘Self’ and the ‘ego’,” in: Man & His Becoming According to the Vedanta, Sophia Perennis, Hillsdale, 2004, p. 24.

[xv] V. Lossky, op. cit., p. 22.

[xvi] A, K. Coomaraswamy, op. cit., 2004, p. 174.

[xvii] Philip Sherrard, The Sacred in Life and Art, Denis Harvey, Evia, 2004, p. 82.

[xviii] T. Burckhardt, op. cit., p. 160.

[xx] A. K. Commaraswamy, “Art, Man and Manufacture,” in: Our Emergent Civilization, R. N. Ashen (ed.), Harper and Brothers, NY, 1947, p. 162.

[xxi] Idem, Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1972, p. 71.

[xxiii] A. K. Coomaraswamy, “Athena & Hephaistos,” in: On the Traditional Doctrine of Art, Golgonooza Press, Ipswich, 1977, p. 19.

[xxiv] Our italicized emphasis. Idem, “The Christian and Oriental, or True, Philosophy of Art,” in: op. cit., 2004, p.132.

Thank you Father Siouan, for this excellent article. It articulates the many important aspects of writing Icons in a clear manner that we all can learn from. For me, it was helpful to have all the nuances explained and documented within the series of the four essays.

Thank you for your valuable work, Christine Simoneau Hales