Similar Posts

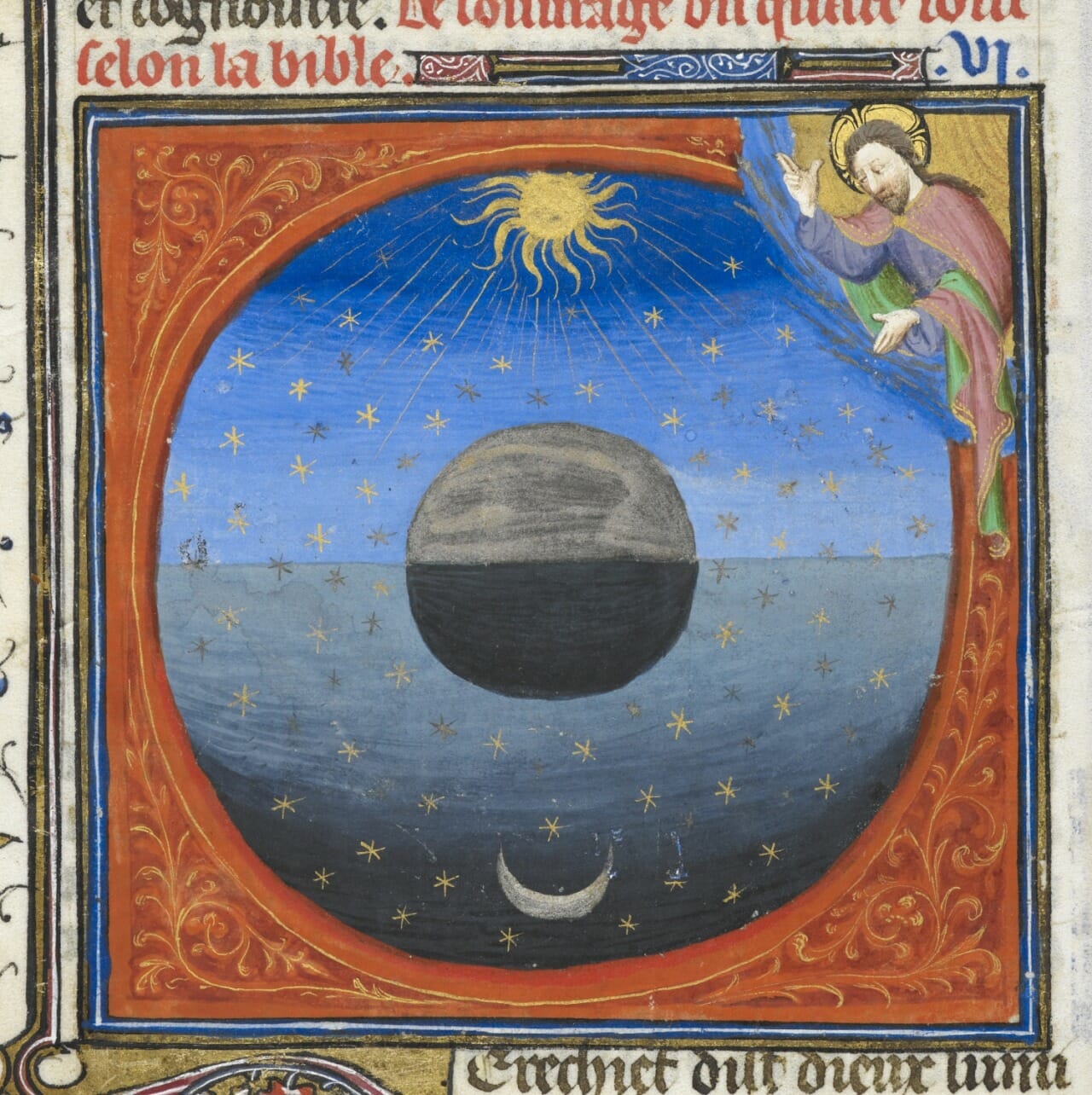

Detail of a miniature of God creating the sun and moon. Bible Historiale, f. 5v by Guyart des Moulins and art by the Master of the Bedford Hours, and the Master of the Cite des Dames. Paris, France c. 1420.

This is part 3 of a series: Part 1, Part 2.

In general the artificial image, modeled after its prototype, brings the likeness of the prototype into matter and acquires a share in its form by means of the thought of the artists and the impress of his hands. This is true of the painter, the stonecarver, and the one who makes statues from gold and bronze: each takes matter, looks at the prototype, receives the imprint of that which he contemplates, and presses it like a seal onto his material.

– St. Basil the Great[i]

Keeping in mind Tradition as defined in our previous post, we can now return to the question of the imagination and expand on its relation to unique modes of expression. Let us start by looking at a passage alluded to earlier from the Natural Chapters of St. Gregory Palamas, which elaborates on the intermediary function of the imagination:

This imaginative faculty of the soul is an intermediary between the intellect [nous] and the senses. For the intellect beholds and dwells upon the images received in itself from the senses […] and it formulates various kinds of thought by means of distinctions, analysis and inference. This happens in various ways – impassionately or dispassionately or in a state between the two, both with and without error. From these thoughts are born most virtues and vices, as well as opinions, whether right or wrong […] When the intellect enthrones itself on the soul’s imaginative faculty and thereby becomes associated with the senses, it engenders a composite form of knowledge.[ii]

So as we can see, as stated earlier and confirmed by St. Gregory, the imagination is a neutral faculty and can contribute either to vice or virtue depending on how it is used. But the thing that should be emphasized here is that in this passage St. Gregory points out how the imagination is also instrumental in engendering composite knowledge. In the Natural Chapters, he goes on to mention that the various kinds of knowledge we attain, with the intermediary help of the imagination, pertain not only to natural science but to “every method and art,” that is techne, or craftsmanship, as defined previously.[iii] In other words, the imagination serves an indispensable demiurgic function in the creative act. Through it we shape, synthesize, clarify and conceptualize mental images. Thereby ideas go through a process of gestation, in which they are gradually given form out of the “subtle” medium, the formless realm of the imagination. These are then given birth in concrete existence, that is, they are externally ex-pressed, whether it be in the form of architecture, music, vestments, vessels, icons, etc. While we are on this earth clothed in “garments of skins,” that is, in a state of mortality, having to supply for our physical and spiritual needs by means of manufacture and symbolic articulations, the imagination will always serve this indispensable function. But, it should not be forgotten that in this process, as St. Gregory notes, the nous, the soul’s governing power or egemonikon, is to “enthrone” itself on the imagination, thereby stabilizing its fluctuating malleability and directing its use as a tool according to the “right course of reasoning.” As Elder Sophrony explains, echoing St. Gregory and calling to mind man as logikos:

We see a third aspect of the power of the imagination when man uses his faculties of memory and imagination to think out the solution to some technical problem; and when he has done so his mind will seek means for the practical realization of his idea. This activity of the reason in association with the imagination plays a vital part in human culture and is essential for the economy of life.[iv]

We can perhaps also think of the imagination as a tablet or parchment unto which the nous sketches, alters, erases and redraws mental images and ideas, according to its spiritual illumination and knowledge of principles. Likewise, as mentioned in the beginning, it can also be compared to a mirror, an image used by Proclus: “And thus we must think of […] the imagination becoming something like a plane mirror to which the ideas of the understanding send down impressions of themselves.”[v] In his commentary on Euclid, he also says, “…so the soul, exercising her capacity to know, projects on the imagination, as on a mirror, the ideas of the figures…”[vi]

Moreover, the craftsman’s process of mental imaging can be said to correspond analogically to the act of creation by the Logos. Just as man has a form or idea in his mind before he imprints it on formless matter, so likewise, there are reason principles or logoi (invisible models or words) in the Logos of God before these are ex-pressed, that is, manifested, given concrete hypostatic existence in Creation from “formless earth” (materia prima).[vii] Therefore, if we keep in mind Aristotle’s definition, it would not come as a surprise that some have called the Logos, the Divine Reason and Son of God “through whom all things were made,” the art of the Father; “…in the same way the art in the human artist is his child through which some one thing is to be made.”[viii] Thus, man, created in the image of God, in his creative act mirrors the Divine Craftsman. But we can even go so far as to say that man as logikos in his imaginative act imitates the original Imaginer.[ix] St John of Damascus points to this correspondence when comparing the invisible models (paradeigmata), archetypes or prototypes of God, to the plans and prescriptions an architect has in mind before he sets out to build:

There are also in God images and models of His acts yet to come: those things which are His for all eternity, which is always changeless…Blessed Dionysius, who has great knowledge of divine things, says that these images and models were marked on before-hand, for in His will, God has prepared all things that are yet to happen, making them unalterable before they come to pass, just as a man who wishes to build a house would first write out the plan according to its prescriptions.[x]

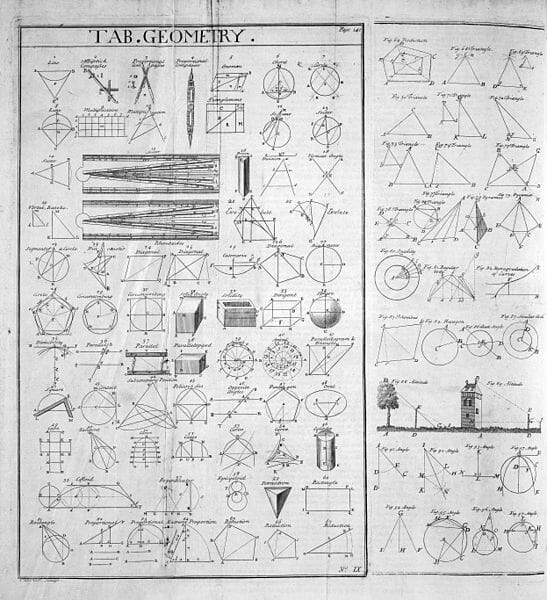

Allegory of Geometry. Miniature is derived from the Burney 275 Manuscript of Euclid Elements, in the Latin translation of the Arabic attributed to Adelardo of Bath, about 1309-1316 (British Library, London).

Implicit in this statement is the fact that the architect does not write the plan before he has first beheld a mental image (paradeigmata) of it in his imagination. This is also taken for granted by St. Nicholas Cabasilas who speaks of the craftsman gazing noetically, within his soul, at the exemplars, models, or mental images he is to follow in executing his work. He says:

It is the practice of painters to depict according to an exemplar, in that they produce their art from preliminary sketches, even when they use their memory to such things and look to the soul for a model. Nor does this apply to painters only, but one may see it in the case of sculptors, architects, and indeed all craftsmen. Were it possible to see the artificer’s soul with the eye one would see the (original) house or statue or other work, apart from the material.[xi]

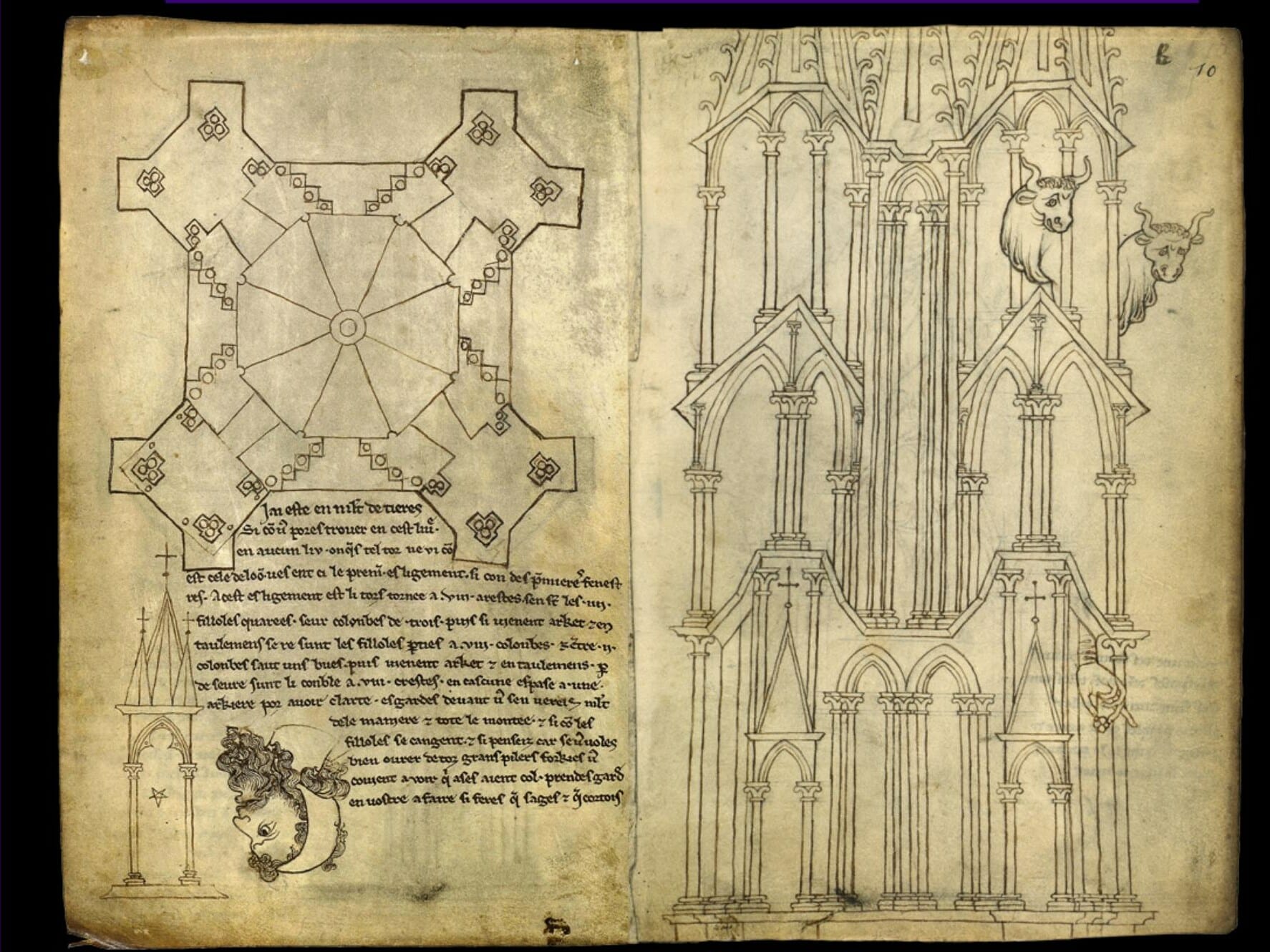

Men wrestling and architectural sketches, from the sketchbook of the medieval craftsman Villard de Honnecourt, Dating about c.1225-1235.

Architectural designs and head in profile, from the sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt, c.1225-1235.

It is clear that here St. Nicholas is discussing the act of craftsmanship in hylemorphic terms, as we discussed earlier. We should also notice that he speaks of exemplars and models as both external and internal to the craftsman. The first is designated by the sketch, the second by the mental image recollected by memory. A recollection which of course, as we saw St. John of Konstradt describe, unfolds through the faculty of the imagination. To “look to the soul, as St. Nicholas puts it, can also be called an act of “mental contemplation.” Hence, St. Theodore the Studite also echoes St. Nicholas when he says in reference to the icon, “…We are taught to draw not only what comes into our perception by touch and sight, but also what is contemplated by mental contemplation.”[xii] But perhaps the best example of an iconographer’s freedom in solely relying on the contemplation, the imaginative recollection of the internal prototype is to be found in the renowned account, of Theophanes the Greek at work, written by Epifanij the Wise c. 1415:

While he delineated and painted all these things no one ever saw him looking at models as some of our painters do who, being filled with doubt, constantly bend over them casting their eyes hither and thither and instead of painting with colors they gaze at models as often as they need to. He, however, seemed to be painting with his hands, while his feet moved without rest, his tongue conversed with visitors, his mind dwelled on something lofty and wise, and his rational eyes contemplated that beauty which is rational.[xiii]

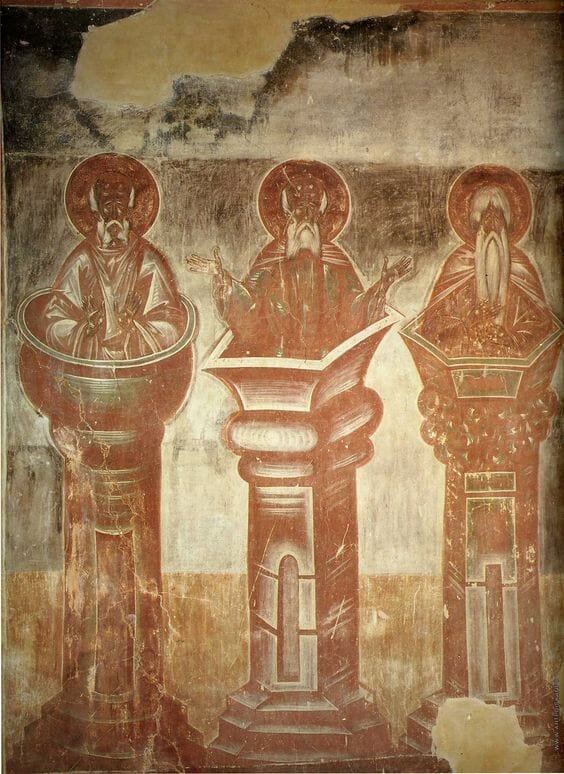

Holy Stylites: Simeon the Elder, Simeon Younger & Alypius, by Theophanes the Greek, 1378. Transfiguration Church, Novgorod.

This, of course, is the highest ideal and not all will attain to it. Nevertheless, it is one worth keeping in mind as a goal to aspire towards by the contemporary iconographer. So the question remains: is the external or internal prototype determining our icons? Both, undoubtedly, it couldn’t be otherwise for most of us, but perhaps without much self-awareness of the imaginative act or mental contemplation that craftsmanship inevitably involves. It seems to me that the general tendency is to think of icon painting mainly in terms of the external sketch or pattern, we have virtually forgotten the inner model – the imagined prototype. We tend to occupy ourselves “only with the surface,” as Kontoglou says. So we end up to undermining what was taken for granted by the traditional craftsman: the positive, crucial, and unavoidable role of the imagination in the creative act. Therefore, we fail to consciously direct it and accrue the efficacious results in iconography. But, here, I believe, is where we find freedom from the mechanical copying Kontoglou warns us about. The process of re-imagining the prototype is “free” in so far as it is not “servile” to mechanically reproducing the surface of the external sketch, but rather noetically apprehends its inner content, its logos or meaning, interprets and re-presents it in a fresh and living way.

The interpretation will inevitably vary from painter to painter, since each individual’s mental image of a given prototype will always be slightly different when solving specific problems. This is unavoidable, for we are all unique individuals, living within unique cultures and a specific historical moment. The painter can even revalorize and synthesize pictorial elements from his immediate or foreign cultures when these are found useful, in conformity and adequate in conveying the content of Tradition. The icon will inevitable reflect, yet not be overwhelmed, by the nuances arising from these contingent factors. Undoubtedly, the essential and unalterable doctrinal elements of the subject are to remain, whether it be an established compositional scheme or the specific likeness of a saint. However, the subtleties of the pictorial method used, such as in the handling of color, line, form, rhythm, proportion of figures and the editing or expanding of compositional detail when possible, will vary from person to person and place to place. If in conformity to Tradition, the icon will be at once time specific and timeless, showing both individual temperament and spiritual objectivity.

To be continued….

[i] As quoted in: St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Icons II: 11, SVS Press, Crestwood, 1981, p. 49.

[ii] St. Gregory Palamas, “Topics of Natural and Theological Science,” in: The Philokalia, Vol. IV, G. E. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware (ed. & trans.), Faber & Faber, London, 1995, pp. 353-354.

[iv] A. Sophrony, “The Struggle with the Imagination,” in: The Undistorted Image: Staretz Silouan 1866-1938, E. Edmonds (trans.), The Faith Press, London, 1958, p. 86.

[v] Proclus, A Commentary on the First Book of Euclid’s Elements, G. R. Morrow (trans.), Princeton University, New Jersey, 1992, p. 98.

[viii] A, K. Coomaraswamy, Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, 1974, p.34; In the words of St. Agustine, “The perfect Word, not wanting in anything, and, so to speak, the art of God,” De Trin. VI. 10.

[ix] B. Keeble, “Notes on Art and Imagination,” in: Daily Bread: Art & Work in the Reign of Quantity, A. Frisardi (ed.), Angelico Press, Kettering, 2015, p. 18.

[x] St. John of Damascus, On the Divine Images: Three Apologies Against Those Who Attack the Icons, David Anderson (trans.), SVS Press, Crestwood, 1980, pp. 19- 20.

[xi] Nicholas Cabasilas, The Life in Christ, C. J. De Catanzaro (trans.), SVS Press, Crestwood, 1974, p. 152.

[xii] St. Theodore the Studite, I: 10, op. cit., p. 31.

[xiii] Epifanij the Wise, “Letter to Cyril of Tver’,” in: The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312-1453: Sources and Documents, Cyril Mango (ed.), University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1986, p. 257.