Similar Posts

The Hand of God from Sant Climent de Taull, Mural Painting, circa 1123. Fresco transferred to canvas, 37.4 in. X 39.37 in.

This is part 2 of a series: Part 1

Because they are the works of God, who is Himself good, the senses and sensible objects are good; but they cannot in any way be compared with the intellect [nous] and with intelligible realities.

-St. Thalassios, On Love, Self-control and Life in Accordance with the Intellect[i]

The modern system of art is not an essence or a fate but something we have made. Art as we have generally understood it is a European invention barely two hundred years old.

-Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art: A Cultural History[ii]

In a traditional art, whether we are concerned with portraits, landscapes, religious images, or birds and animals, the artist’s point of view is never realistic [naturalistic], but conceptual, in that he intends to represent the most essential or typical aspects of things as the mind knows them, rather than as the eye sees them.

-Benjamin Rowland, Jr., Art in East and West[iii]

Before we proceed to explore further the creative act, and in order to supply a context to what will follow, it is important to clarify what we mean by the terms nous, art and Tradition. We can begin by approaching the term nous by way of the icon’s distinctive pictorial language.

One of the clear differences to keep in mind between post-Renaissance religious painting and the icon, is that the latter’s power as a sacred art derives not only from its religious subject matter, but more importantly from the particular manner this subject matter is expressed. While the first displays a predominantly humanist and empiricist orientation; the second is guided by metaphysical and symbolic considerations. As Titus Burckhardt puts it, “…there is a rigorous analogy between form and spirit. A spiritual vision necessarily finds its expression in a particular formal language.”[iv] Hence the icon relies more on hieratic and abstract stylization, than on illusionist naturalism, as a way of symbolically intimating the existence of divine realities.[v] In surpassing outward appearances, it aims to penetrate into and “draw out” those essential elements that best communicate the inner truth of the subject depicted. Its task is to convey the intuition of persons and the world transfigured, imbued with divine grace, aflame but not consumed as they participate in the divine nature.[vi] Thereby the icon serves an interiorizing function, leads to prayer and places us in the presence of the Sacred. Thus the icon re-presents a way of seeing not merely according to the carnal eye, but with the eye of the heart[vii], what the Fathers call the nous (in Latin intellectus).

The nous, is to be understood as “the highest faculty of man, through which – provided it is purified – he knows God or the inner…principles of created things by means of direct apprehension or spiritual perception.”[viii] Moreover, as Jean-Claude Larchet explains:

The nous represents the contemplative possibilities of the human being. For the Fathers it is fundamentally that which links man with God, that leads him towards and unites him with God. By means of the nous man is objectively and in a definitive manner linked to God from the moment of his creation: the nous is in effect the image of God in man. This image can be masked or soiled by sin, but it cannot be destroyed: it is the indelible mark of man’s most profound being, of his veritable nature, the logos or constitutive principle of which cannot be altered.[ix]

Charioteer and Horses, painted tomb slab detail. National Archaeological Museum, Paestum, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Campania, Italy. As the charioteer skillfully steers the unruly horses in the right direction towards his goal, so is the nous to guide and direct the incensive and desiring powers of the soul towards the good by the reins of virtue.

Although the nous is higher than discursive reason (dianoia), the Fathers at times group these together when designating man as logikos, or rational, capable of governing himself and having freedom to make moral choices. Therefore the nous, as man’s highest faculty, is often called the egemonikon, since it is that power meant to direct the faculties of his whole psycho-somatic constitution towards the divine will.[x] The nous is also referred to as the spirit (pneuma) of man. Thus its “direct apprehension,” or intuition, is to be understood as seeing in the spirit according to the Spirit[xi], above abstract concepts, deductive reasoning, subjectivism, passions and fantasy.[xii] In short, the nous can apprehend reality objectively and grants certitude. This intuition encompasses a wide spectrum, from the loftiest forms of prophetic vision, to the more immediate knowledge of God through the beauty of Creation. Thus it also embraces the various forms of sacred art within the Church, which symbolically manifest the multifarious levels of this spiritual perception. The pictorial principles of iconography[xiii], harmoniously uniting the various national and stylistic schools, have arisen from centuries of collected artistic experience shaped by this inner vision, which from here on we will refer to as noetic intuition. As Aidan Hart puts it, “The way an icon is painted comes of this noetic way of seeing and in turn is designed to introduce the faithful into this noetic way of seeing.”[xiv]

***

As mentioned earlier, it is often said that the icon is not to be confused with “art,” a statement that needs some clarification, as it can be easily misinterpreted. Ironically, although used to emphasize the primary importance of the icon’s theological function over mere aestheticism, it at times ends up belittling its creative import and demands. Hence, some begin to think that anyone can paint an icon, since it only involves a strict conformity to “canonical” patterns in a step by step process, a kind of “color by numbers” method. Moreover, the icon’s abstract stylization becomes an excuse for the worst of distortions, which only betray lack of skill in the general principles of painting. So, if we are not cautious, we can unwittingly be left with ugliness and artistic ineptitude hailed as virtues, cloaked under the pietistic pretext: “The icon is not ‘art.’”

On the one hand, we would have to say that this statement is only partly true, if we mean by it that the icon is not to be confused with “gallery art.” That is, the icon is not an autonomous art object, “art for art’s sake,” an end in itself, an individualistic statement. But, on the other hand, it is a very specific kind of art, a liturgical art, and as such a major component in the “total work of art” of Church cult, the Divine Liturgy, in which various arts participate to create a harmonious synthesis, centered on the Eucharist and contributing towards the deification of man.

Bezallel and Aholiab at Work.

Paduan Bible Picture Book. Londra, British Library, ms Add (Additional) 15277, f 16. Originally published/produced in N. Italy, last quarter of 14th century.

Moreover, the icon is most definitely an art in the traditional sense of the word techne, in Latin ars, from which we derive the word art, meaning craftsmanship, the skillful joining together, or making, according to the right course of reason (logos), as Aristotle puts it in his Nichomachean Ethics.[xv] Hence art is to be understood as the “principle of manufacture”[xvi] applied towards a specific purpose or end and remains in the artist as knowledge.[xvii] According to this understanding there is no stark difference to be made between so-called “fine art” and crafts, artist and artisan, symbolic meaning and utility or beauty and function, as we have it today.[xviii] As Elder Aimilianos tells us, “…For the ancients and for Scripture, no distinction was made between art and artifacts (technology)[xix], which, if they corresponded to the needs of our nature, could hardly be foreign or hostile to ‘beauty’.”[xx] In traditional integrated civilizations, such as the medieval West and Byzantine East, under the category of “art” fell not only one kind of making, but rather many, from the arts of painting, sculpture, architecture, masonry, calligraphy and farming; to that of music, poetry, rhetoric, philosophy, teaching and ruling, among many others.[xxi] Moreover, the traditional artist spoke, not from his individualistic isolation with an arbitrarily invented artistic language, but rather with a lingua franca, in unison with the mentality of an international community, imbued and ordered around religious principles.[xxii]

So it is important to realize that this “traditional doctrine of art,”[xxiii] which has actually been held as the norm from time immemorial, is still to be found in the Orthodox Church in its various forms of sacred or liturgical art, our modern conceptions of “fine art” being rather the anomaly in the history of civilization.[xxiv] With the radical shift that has taken place in culture, from a theocentric to an anthropocentric orientation, reflecting the revolt of reason against the nous, a great divorce has taken place between art and its primordial function as a symbolic embodiment and vehicle for the presence of the Sacred. Indeed, there is no doubt that:

When art loses its way, it loses it because it severs itself from its spiritual role, as a quest for God, a quest for a transfigured world, a quest for timeless truth in the midst of suffering. The word “art” means to join fitly together, and if we look throughout history the art of most cultures has aimed to join together the divine and the earthly realms, has had a religious function: Egyptian, Greek, African, Indian, Chinese, virtually all. Art without a spiritual aim is a recent and western phenomenon.[xxv]

So it could be said that liturgical art is in fact the highest realization of the function of art, that is, the skillful act of “joining together,” since it serves to reconnect us to God Himself. Thus it is the culmination of art’s incarnational import, its capacity to unite Heaven and earth, the Uncreated and created, Archetype and symbol. In serving as a vehicle and embodiment of the Sacred, it is a witness to the sanctification of matter that has ensued as a consequence of the Incarnation of the Logos. We can then begin to see how within this context iconography is not to be seen as requiring less creative engagement than our contemporary notions of “fine art” demands, as some might think. Rather, in being more complete and having a higher purpose, it demands the most out of us, requiring the mastery of pictorial principles, craftsmanship skill, intellectual rigor, noetic intuition and theological knowledge – the coming together of creativity and spiritual discipline, functional and symbolic values. All of which unfolds in accordance with Tradition.

***

But what do we mean by Tradition? By Tradition we do not mean the legalistic use of ossified forms, mere conventional conservatism, academicism, nor antiquarianism.[xxvi] This would limit and relegate Tradition solely to the contingent and human domains. We rather mean the ever new and ever renewing witness of the Holy Spirit in the Church[xxvii], through which we come to the knowledge of the Mystery of the incarnate Logos – the “pre-eternal council” of the Holy Trinity – which has been made manifest, and still continues with us today in its deifying efficacy.[xxviii] Or, as described by the English painter Cecil Collins, it is “…that continuum of knowledge which deals with the meaning and purpose of man’s life, and with the possibility of his rebirth. It is a knowledge ever new, fresh, immortal, always present, not subject to time…”[xxix] In short, it is nothing other than access to the Revelation.

From the Greek paradidomi (in Latin traditio), the word “tradition” denotes the transmission, or a “handing down,” of Revelation in various forms, whether these be in oral, written, gestural or artistic symbolism. Thus the word implies, as its two primary aspects, an inner and outer dimension, which in turn presuppose trans-temporal and temporal aspects, a vertical (divine descent) and horizontal (living continuity) axis of manifestation.[xxx] Its inner dimension pertains to the Logos Himself, “handed down” by the Father to become man, and the immutable principles of the Gospel (or “the Way” as referred to by ancient Christians) imparted to the Apostles. The outer then pertains to the various forms of embodiment and application of these first principles in all aspects of life (active and contemplative) within the Church, the Body of Christ, from which it derives its integrated character as one organism, enlivened by the grace of the Holy Spirit.

Indeed, Tradition is immutable and living, expressed in a multiplicity of artistic forms, whether these be images, poetry, homilies, architecture, carvings, hymnography, music, chanting, garments, rites, etc., – all of which do not exhaust the unfathomable depths of Tradition. These remain in their particular formal conventions, which have been tried and tested for centuries, unalterable in so far as they continue to function as adequate symbols of Truth. The Church then has the liberty, through the power and inspiration of the Holy Spirit, to alter these according to pastoral necessity if necessary. The forms arise from but do not stand above Tradition. For as Vladimir Lossky puts it:

If the Scriptures and all the Church can produce in words written or pronounced, in images or in symbols liturgical or otherwise, represent the differing modes of expression of the Truth, Tradition, is the unique mode of receiving it. We say specifically unique mode and not uniform mode, for Tradition in its pure notion there belongs nothing formal.[xxxi] It does not impose on human consciousness by formal guarantees of the truth of faith, but gives access to the discovery of their inner evidence.[xxxii]

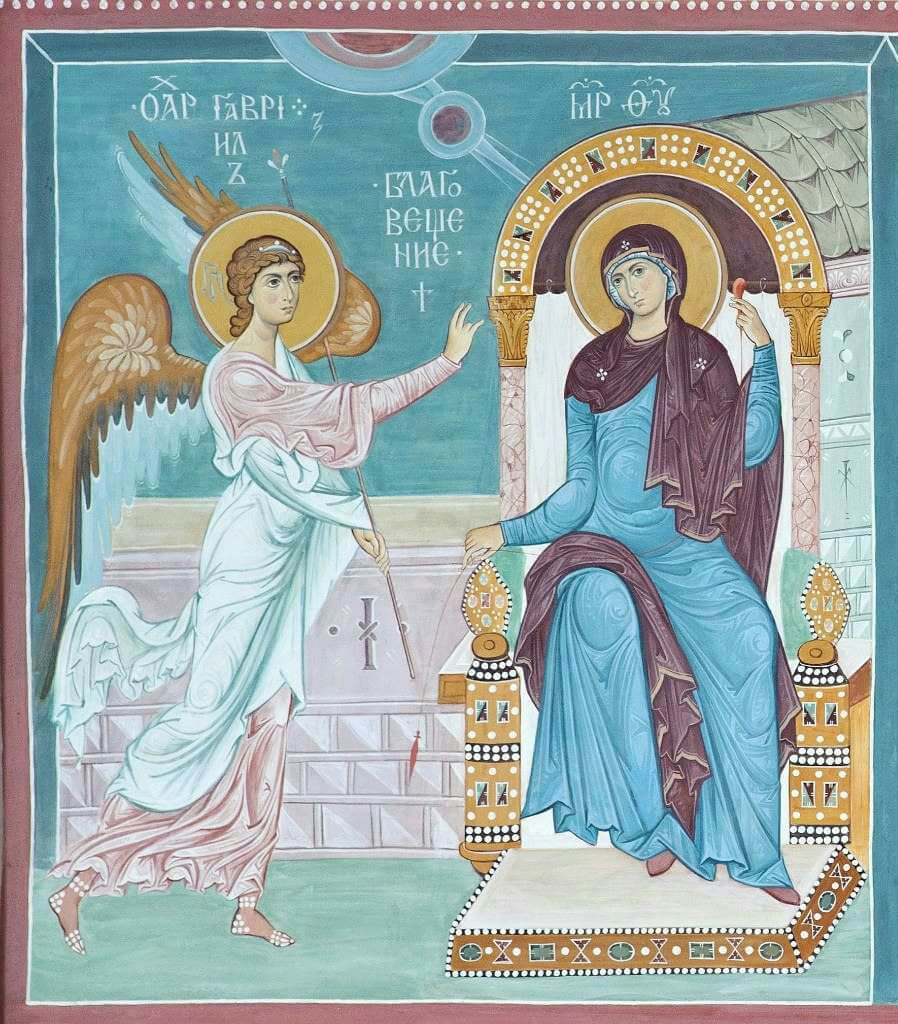

But this, of course, is not intended as a facile excuse for dismissing and dismantling all formal expressions of Tradition arbitrarily, as if we have to “update” things, according to external criteria “after the rudiments of the world” (Col ii, 8), based on revisionist historicism, higher criticism, and progressivist notions. Far from it. The living continuity of Tradition is not predicated on keeping up with the zeitgeist. On the contrary, it is a caution against the kind of formalism that tends to mistake the surface for the inner reality, the letter for the spirit of Tradition. Both extremes, whether willful innovation or hardening formalism are to be avoided. This is very pertinent when it comes to the icon, for it is clear that in the course of history Tradition has found expression in a variety of styles reflecting personal and cultural temperaments, different levels of noetic intuition and artistic mastery, as iconographers have creatively confronted needs and resolved immediate problems of craftsmanship. In other words, we find vitality rather than a legalistic use of ossified forms, without succumbing to the excesses of individualistic innovation.

The Annunciation, at the Castel d’Appiano, in Trrentino/Alto Adige, AKA the south Tyrol (in the Alps), ca. 1200.

The Annunciation, contemporary icon.

Therefore, Tradition cannot be trapped into just one approach or mode of expression, no iconographic style or school can claim monopoly to the “most authentic” formula, although it might be firmly grounded on the doctrinal demands of the icon or on what can be called its “timeless” pictorial principles.[xxxiii] It should be kept in mind that these principles are not purely static, but rather extremely flexible and expandable. They are not the Tradition itself, but that which makes up its glorious garment, the efficient grammar and letters of a language, giving clear expression and manifesting the unfathomable depths of Tradition. And like all languages they go through organic changes. The pictorial principles derive their timelessness and accuracy insofar as they participate in immutable Tradition and function efficiently to symbolically manifest it. From this participation they become the unifying components in the diversity of pictorial dialects or styles of the various schools clearly evident throughout history, such as the Mecedonian, Comnenian, Palaeologan, and Cretan along with the Romanesque, Coptic, Romanian, Georgian, Cappadocian and Russian schools, among others. The styles can perhaps be called the unique, rather than the uniform, modes of embodying and expressing the noetic intuition of the Truth imparted by Tradition.

In other words, there is room for dynamic creativity in cooperation with the Holy Spirit. Obedience to Tradition does not stifle or deaden, but rather paradoxically transforms, revitalizes, purifies and resurrects, persons and cultures to the fullness of their unique creative capabilities. Thus, the “unity in diversity” of iconographic styles within the Church attests to the continuity of Pentecost, in which each culture and individual gift contributes to the edification of the whole Body of Christ.[xxxiv]

To be continued….

Notes:

[i] St. Thalassios, “On Love, Self-control and Life in Accordance with the Intellect,” in The Philokalia, Vol.II, Faber and Faber, London, 1981, p. 326.

[ii] Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2003, p. 3.

[iii] Benjamin Rowland, Jr., Art in East and West: An Introduction Through Comparisons, Beacon Press, Boston, 1964, p. 2.

[iv] Titus Burckhardt, Sacred Art in East and West: Its Principles and Methods, Lord Northbourne (trans.), Perennial Books LTD., Pates Manor, 1986, p. 7.

[v] It goes without saying that the ineffable and unfathomable Divinity cannot be circumscribed or depicted as such. Nevertheless, all forms of symbolic representation implemented by the sacred arts of the Church aim to elevate us to and facilitate the contemplation of divine mysteries. The sacred arts can then be described as “veils,” boundaries between the sensible and intelligible, which both conceal the “divine darkness,” while yet revealing in various degrees the radiance of its glory. As Aidan Hart notes, “…through its formal or stylistic qualities an icon can also be a means of transforming the way we see things. While…the Seventh Ecumenical Council…makes it clear that icons cannot depict invisible divine realities as such, the ancient witness of icons themselves show that icons through symbolism do indicate their existence. All icons of the transfiguration, for example, indicate Christ’s glory by painting a nimbus around Christ. After all, the Church Fathers had no hesitation in writing about divine things, albeit in a very guarded and provisional way.” Aidan Hart, “Today and Tomorrow: Principles in the Training of Future Iconographers,” in: Orthodox Arts Journal, 19 May, 2016, https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/today-tomorrow-principles-training-future-iconographers-pt-1/ (accessed 23 November 2016).

[vi] On “searching beyond ‘ordinary’ nature” in art, which in some ways parallels this understanding of the icon see: Jean Borella, The Crisis of Religious Symbolism & Symbolism and Reality, G. J. Champoux (trans.), Angelico Press/Sophia Perennis, Kettering, 2016, p.236.

[vii] As Archimandrite Ioannikios Kotsonis notes, “According to St. Gregory Palamas the intellectual activity, consisting of thought and intuition, is called nous, and the power that activates thought and intuition is likewise the nous and this power the Holy Scripture also calls the heart. It is because the heart is pre-eminent among our inner powers that our soul is deiform.” On the “eye of the heart” see St. Macarius, Homily 43: 3, in: Pseudo Macarius, Fifty Spiritual Homilies and the Great Letter, G. A. Maloney (ed. & trans.), Paulist Press, 1992, p. 221- 222.

[viii] From the Glossary of The Philokalia, G. H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware (eds.), Faber & Farber, London, 1979, Vol. I, p. 362.

[ix] J. C. Larchet, Mental Disorders and Spiritual Healing: Teachings from the Early Christian East, Rama Coomaraswamy & G. J. Champoux (trans.), Angelico Press/Sophia Perennis, San Rafael, 2005,

[x] Commenting on St. Maximos the Confessor’s understanding of nous as egemonikon, Fr. Demetrios Harper says: “It is important to stress that the intellect [nous] leads because of its capacity to perceive God’s intentions (λόγοι) for created nature, the collective totality of which, in Maximu’s view, constitute the natural law…Yet the intellect’s natural hegemony is not realized through the abrogation or suppression of the other human powers.” Fr. D. Harper. op. cit., p. 4.

[xi] The spirit is “the ‘breath’ from God (see Gen. 2:7), which animals lack.” However, it is important to stress the distinction that exists in the Orthodox metaphysic between the spirit of man (created) and the Holy Spirit (uncreated), the two are not to be conflated, although they are intimately connected. B. K. Ware, op cit., p. 48.

[xii] That is, surpassing a “soulish” (psychic) way of seeing, which is mainly relegated to the assimilation of the material domain through the faculties of the reason (dianoia) and the senses. As St. Paul says, “The unspiritual [psikikos in Greek, literally “soulish”] man does not receive the gifts of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to know them because they are spiritually discerned” (1 Cor. 2:14).

[xiii] These are often called the icon’s “canonical” or traditional formal language. Clarifying the meaning of the iconographic “canon,” Irina Yazykova says: “And in prayer with icons, each image serves to concentrate and focus our spiritual sight…In order to express this focus on Christ, a special pictorial language was gradually developed in iconography: it is this language that forms what is called the iconic canon. This existence of this canon should not be understood as some iron cage circumscribing the freedom of the icon painter. Rather, it represents simply a central core of meanings that ensure that the iconic image is filled with the appropriate doctrinal and theological content.” I. Yazykova, Hidden and Triumphant: The Underground Struggle to Save Russian Iconography, Paraclete Press, Brewester, 2010, p. 4.

[xiv] Aidan Hart, “Liturgical Arts and the Eye of the Heart,” in: Orthodox Arts Journal, 25 June, 2012, https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/liturgical-arts-and-the-eye-of-the-heart/ (accessed 23 November, 2016).

[xv] Nichomachean Ethics VI: 4; B. Keeble, “Of Art and Skill,” in: op. cit., 2015, pp. 44-55.

[xvi] An expression of T. Aquinas, based on Aristotle, often quoted and explicated by Coomaraswamy. See: A. K. Coomaraswamy “A figure of Speech or a Figure of Thought?” in: op. cit., 1204, p. 32; idem, The Nature of Medieval Art, Ibid., pp. 173- 176.

[xvii] “As the words ‘artifact’ and ‘artificial’ imply, the thing made is the work of art, made by art, but not itself art; the art remains in the artist and is the knowledge by which things are made.” A. K. Coomaraswamy, op. cit., 1972, p. 18.

[xviii]A. K. Coomaraswamy, “Mediaeval and Oriental Art,” in: Traditional Art and Symbolism, Roger Lipsey (ed.), Princeton University Press, 1989, p. 51.

[xx] Elder Aimilianos ads, “Art precedes mechanics, being of greater necessity, while technology developed, not to serve the highest concerns of Man, but with the aim of greater production and profit.” Archimandrite Aimilianos, “Orthodox Spirituality and the Technological Revolution,” in: The Authentic Seal: Spiritual Instruction and Discourses Vol. I, Ormylia Publishing, Ormylis, 1999, p. 347.

[xxi] A. K. Coomaraswamy, op. cit., 1989, p. 51.

[xxii] Idem, “The Medieval Theory of Beauty,” in: Ibid., p. 189.

[xxiii] Idem, 1977, op. cit.; Idem, 1972, op. cit.; Idem, Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought?: The Traditional View of Art, World Wisdom Inc., William Wroth (ed.), Bloomington, 2007; T. Burckhardt, 1986, op. cit.; B. Keeble, 2005, op. cit.; B. Rowland, Jr., “Traditional and Non-Traditional Art,” in: Art in East and West: An Introduction Through Comparisons, Beacon Press, Boston, 1954, pp. 1-6.

[xxiv] See Dr. Larry Shiner, op. cit.

[xxv] Aidan Hart, “Holy Icons in Today’s World (Part.2): Icons and Modern Art,” in: Orthodox arts Journal, 21 March 2014. https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/holy-icons-in-todays-world-pt-2-icons-and-modern-art/ (accessed 23 November 2016).

[xxvi] “…for custom without truth is the antiquity of error.” St. Cyprian, Epistle 73: 9.

[xxvii] Georges Florovsky, “Bible, Church, Tradition: An Eastern Orthodox View,” in: The Collected Works, Vol. I, Nordland Publishing Company, Belmont, 1972, pp.46- 47.

[xxviii] See, T. Ware, “Holy Tradition: The Sources of the Orthodox Faith,” in: The Orthodox Church, Penguin Books, London, 1997, pp. 195- 207.

[xxix] Cecil Collins, “Why Does Art Today Lack Inspiration,” in: B. Keeble, 2005, op. cit., p. 203.

[xxx] For the inner and outer dimensions of Tradition see: T. Ware, 1997, op. cit.; B. Keeble, “Tradition, Intelligence and the Artist,” in: Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 11, no. 4., Autumn, 1977, http://www.studiesincomparativereligion.com/Public/articles/browse_g.aspx?ID=317 (accessed 23 November 2016).

[xxxi] It hardly needs mentioning that, in making a distinction between the “pure notion” of Tradition and its various formal expressions, neither we nor Lossky are alluding to the doctrine of the transcendent unity of religions.

[xxxii] V. Lossky, “Tradition and Traditions,” in: L. Ouspensky and V. Lossky, The Meaning of Icons, G. E. H. Palmer & E. Kadloubovsky (trans.), SVS Press, Crestwood, 1989, p.15.

[xxxiii] See: Aidan Hart, “The Timeless Principles Common to All Schools,” in: Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting: Egg Tempera, Fresco, Secco, Gracewing, Leominster, 2011, pp. 29- 31; Idem, op. cit., 2016; George Kordis, Icon as Communion: The Ideals and Compositional Principles of Icon Painting, Holy Cross Press, Brookline, 2010.

[xxxiv] Aidan Hart, “Diversity Within Iconography: An Artistic Pentecost,” in: New Liturgical Movement: Sacred Liturgy & Liturgical Arts, 24 July, 1211, http://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2011/07/aidan-hart-on-diversity-within.html (accessed 23 November 2016).