Similar Posts

Yesterday, Jonathan Pageau posted an article in which he juxtaposed two videos – one of the carving of an icon by hand, and another of the carving an icon by a computer-controlled machine. Jonathan expressed an intuitive attraction to the one and dislike of the other, and suggested the difference as being of a spiritual nature. I completely agree, but I would like to discuss the matter further, approaching it from the perspective of a liturgical designer and manufacturer.

I happen to be someone who is highly interested in machine manufacturing as well as hand crafts. I sometimes take my lunch hour watching YouTube videos of robotic equipment that makes gears, ball bearings, window glass, etc. I marvel at how these machines can produce with absolute uniformity and incredible speed, making precise parts far better than they could be made by hand. There is great beauty in watching these machines at work. They are so perfectly suited to what they do. They work with the same beauty of economy that we enjoy when we watch a lion hunt, an eagle soar, or a dolphin swim.

So how then do I view the role of robotics in liturgical art? To me, the first question is whether the machine can actually do the job well. Is it a craft that is suited to the machine’s ‘skill set’ (if you can say such a thing about a machine). This question cannot be asked generally, but only with regards to a specific case. Let us begin with the CNC rotary carver in Jonathan’s video. This machine has two huge problems from an engineering standpoint. First, it cannot actually carve wood. It can only grind wood with its high-speed rotary bit. Thus it leaves a rough fuzzy surface. Secondly, it has terrible resolution. It cannot carve any detail smaller than the diameter of the bit itself. It could theoretically change bits as the carving gets more detailed, but even the smallest rotary bit cannot make the required sharp edges in a carved icon. Whereas the hand carver produces an icon with smooth burnished surfaces and precise details, the machine produces one that is dull and fuzzy, with all edges crudely rounded. To give it a decent finish would require someone to hand-sand the whole thing, which would further round-over the details, and further dull the luminosity of the wood. (Hand-carvings are never sanded, because the sharp chisels leave a perfectly smooth surface with open grain pores, coaxing a luminous chatoyant luster from the grain. Sanding fills the pores with dust and dulls the beauty of the wood considerably.)

Thus, I would have to say that the CNC rotary carver is simply unsuitable for the task. It produces a markedly inferior product. And it does not even do so particularly quickly. This, I submit, is why the video of that machine at work is unbeautiful and unpleasant to watch, grinding away big and small areas alike with the same bit, always fighting against the grain rather than cutting with it. In contrast, the hand carver at work is beautiful to watch (Jonathan calls it “liturgical”, and isn’t ‘beautiful work’ the very nature of liturgy?). The hand carver is always choosing the tool that makes the most efficient cut, and holding it at the best angle and orientation, thus removing each slice of wood cleanly with minimal use of force. Indeed, the hand carver is a model of efficient engineering!

There is a second, longer term, question of what effect does the machine have on the lives and skills of those whom it has replaced. Allow me to treat this not as a moral question, but as a purely practical one. When a hand craft is given over to a machine, the skills of men must adjust to become operators of the machines. This does not always mean a reduction of skill. The operator of a backhoe is more skilled than the laborer who digs ditches by hand. Let us examine this question with regards to the icon carver.

A hand-carver of icons must be a sculptor. He must know everything about the artistic construction of the image. The use of chisels and gouges is a mere technical skill, and it can be learned by most people with a little practice. But the artistic skills of a real icon sculptor take years to learn, and probably few people have the innate talent to ever master it. Now how is this icon sculptor to impart his knowledge to the carving machine? The only practical way is to use a 3D scanner to scan an existing sculpture. The software takes it from there. The machine operator thus has no use whatsoever for artistic knowledge. His job is to run the software, insert the wood, clean out the sawdust, oil the gears. He can produce icons forever just by scanning a few old existing ones. Thus is should be obvious that the art of sculpted icons will ultimately decline if they are machine produced. There will be no reason for anyone to master the art, as there will never be enough commissions to support such a master. Whenever there is this complete divorce between artist and machine, the machines inevitably become the purview of inartistic people who make inartistic decisions. Before long it is an industry and market that feeds on itself, and all thought of trying to match the quality of hand-carved icons is eventually forgotten.

But it is not necessarily so with other crafts. Consider another use of the CNC rotary carver – the making of icon boards. To carve out the kovcheg depression in an icon board is slow boring work. The goal is to make it as flat and uniform as possible. All marks of the carving tool must be sanded out before gesso is applied. Almost everyone now uses a router to carve the kovcheg. Some have had the idea to use a router guided by CNC robotics, and why not? The machine is perfectly suited to this simple repetitive task. It can do it better and faster. It reduces the cost of good icon boards, which is clearly good for iconographers. And it frees up skilled woodworkers to put their time into more visible liturgical crafts. Perhaps something is lost of the monkish beauty of a carver spending an hour hand-carving a rectangle, but not all board-makers are monks, and even monks do not eschew machines if they give them more time to pray.

In my own work I use robotics extensively in the manufacture of Byzantine-style chandeliers. These fixtures consist mainly of sheets of metal perforated with decorative fretwork. The ancient examples were cast bronze – a very expensive technique. I like the blue-black color of these fixtures when made out of oxidized steel. When I design them from scratch, I draw my fretwork patterns by hand. Then I scan and trace them in AutoCAD and send them to a CNC cutting facility. A plasma-cutter mounted on a robot cuts them out of sheet steel. The plasma cutter leaves a smooth melted surface with an interesting wavy texture. It actually looks better than if I were to hand-cut them with a saw, or sand cast them and buff out the casting flaws. In the case of flat fretwork, all the artistic skill lies in the designer’s drawing rather than in the cutting out. Thus there is no loss of skill to have the cutting done by robotics, and no threat to the future of the art.

I also design furniture in the Old-Russian style which includes fretwork cut from wood. It is possible to make this fretwork with a CNC laser cutter. But I do not do this. A laser cutter burns the edges of the wood, which makes for an untraditional aesthetic. Personally, I find these burnt edges quite disturbing. So I cut my wood fretwork by hand. However, if had reason to make a large quantity of wood fretwork that was going to be painted, I would definitely consider laser cutting. The decision would be purely technical.

A candelabrum in the style of 17th-century Russian woodwork, with hand-cut fretwork. Made by the author.

It is also worth mentioning cast metal icons. Casting is an ancient and traditional means of mechanically reproducing an icon. In old times, the process of lost-wax casting metal was highly labor intensive, and prone to failure. Nowadays, bronze is lost-wax cast using computer-controlled vacuum kilns. This is a good example where the machinery helps rather than hinders the quality of the craft. But modern casting techniques also bring the temptation to cast in cheaper materials – pewter or zinc, which are cold and lack the durability of bronze – or polymer plastics – a dull and depressing material that frequently seeks to falsify ivory. With any good technology that saves money, there is always the temptation to save more money by reducing quality. There is no room for this in liturgical arts made for the glory of God. The liturgical artist must walk the narrow path between the technology of the world and service of Our Lord.

I hope I have illustrated my thinking with regards to robotic manufacture. I see these advanced machines as tools, not as soul-less craftsmen. I do not see an automatic distinction between hand-made originals and machine-made reproductions. Clearly the CNC-cut steel chandelier or the robotic-cast bronze icon, are original works of art, not reproductions of a hand-made piece. The term reproduction implies a somewhat deceptive copy with a loss of quality – something that seeks to look like something it is not. The CNC-carved icon falls into this category. The question of reproduction also brings with it the consideration of printed icons.

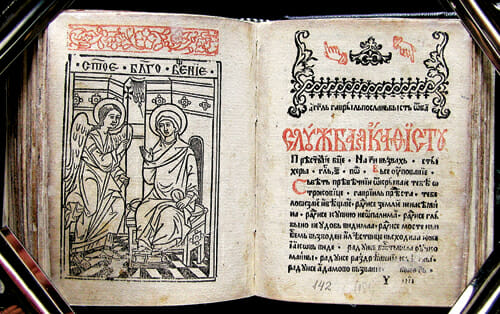

Printed icons were not always made by machines. Antique liturgical books are full of printed icons. These are wood-block prints, made by master carvers, and clearly original works of art in their own right. They do not attempt to replace nor even resemble painted icons; their aesthetic expresses their own unique way of being made. But printed icons nowadays are robotically-manufactured reproductions of paintings. The studios that make them have an inexhaustible supply of photos of icons to choose from. Thus there is no need for a master icon painter to be involved. There is apparently little concern that the printing machine simply cannot make an image that has the richness and transparency of a really good painted icon. We must be honest and acknowledge that these prints are not the visual equivalent of egg-tempera and gold leaf, not even close. And without artists to guide the process, this modern craft has not developed an honest aesthetic that expresses its unique qualities and potential. The printers of icons can only think to glue their prints to boards so as to better imitate paintings. Thus the photo-reproduction of painted icons is another example where the product is necessarily inferior, and the inartistic context of production inevitably leads to loss of skills and lowering of standards.

But even here, there is no reason to eschew the printing press from the sacred arts. Modern presses can make very good liturgical books. And a good designer can illustrate those books with monochrome icons modeled on the old wood-block prints – an aesthetic highly appropriate to printed books. Thus even printing machines can be taught to make good and honest liturgical art. After all, robots do as their told, and their work is only a reflection of our wisdom or folly.

I love the careful thinking and distinctions made here. I would also, however, point out that computer illustration, as an original work of art (as opposed to a picture of a painting, for example), is largely unexplored as a medium in the Orthodox iconographic world. It has been heavily explored by the art of the world, on the other hand. I think it might be high time for us to baptize that space as well…

God’s presence is “transmitted” not in the intense heat of a plasma-cutter or the high pressures of a water-jet but in the act of breathing which “recalls” man’s first memory of the creative act (cf. Gen 2:7 and 1 Kings 19:11-12). Breath and soul (“np̄eš” and “nap̄šā”) are analagous in Aramaic. Super article.

Thank you very much for the great article Andrew!

It succinctly clarifies and fills in a lot of blanks in the answer to this complex question.

I’m glad you brought up the wood-cut technique and the printing press as not necessarily incompatible in the realm of sacred art. For a while now I’ve been thinking about icon wood-cut prints as a “middle ground” so to speak when it comes to the problem of icon reproductions. The wood-cut print, although reproducible in large quantities, does not try to duplicate other techniques. It acts on its inherent properties as a graphic medium. Pictorial properties that are not too foreign to the graphic, “abstract”, and linear qualities of the icon. If the wood-cut medium is handled with nuanced craftsmanship, I believe the beauty of its material properties can make of it a good substitute, over photo reproduction, for personal devotional use. It might not be the answer for communal liturgical use, but at least it buffers to some degree the overabundance of reproductions in the realm of personal piety. Perhaps, the icon wood-cut print is a venue to explore. I would appreciate your thoughts on this. Thanks again.

Fr. Silouan

I completely agree. As usual, the secular world has thought of this first. There is a huge revival in letterpress printing right now. There are dozens of print shops that use antique wooden type to make high-end greeting cards and wedding invitations. If the secular world now feels that important printed items should be lovingly hand-printed in this way, then why is the Orthodox world still printing icons on inkjet printers? Shame on us.

I have for some time been thinking about letterpress or block printing of icons. It’s easy to imagine them for Orthodox greeting cards, but I’ve struggled with the question of how to present them for liturgical or devotional use. It will take some creative thinking.

Graphic designer Valerie Wilson is already experiementing with icon-like letterpress cards. Unfortunately, she chose to do everything in metallic foil.

By the way, I am not sure I like being called a load!

[…] arts (starting with fr. Silouan Justiniano’s article, my short post and Andrew Gould’s response), I thought I would attempt something I have been contemplating for quite some time now, that is […]

Thank you for continuing this meaningful conversation. Godspeed in all your work!