Similar Posts

____________________________________________________________

Editorial note: We have convinced Aidan Hart to post a chapter from his new book. “Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting” which is being hailed as the most comprehensive book to date on practicing the art of Iconography. At 450 pages, with 460 paintings, 150 drawings and covering everything from theology and design to gilding and varnishing, it is a prized possession for anyone interested in the traditional arts. The chapter being serialized over the next weeks is called “Designing Icons”. You will see why Archimandrate Vasileos of Iviron called this book the “Confessio of a man who epitomizes the liturgical beauty of the Orthodox Church”. More details about the book on Aidan’s website.

Editorial note: We have convinced Aidan Hart to post a chapter from his new book. “Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting” which is being hailed as the most comprehensive book to date on practicing the art of Iconography. At 450 pages, with 460 paintings, 150 drawings and covering everything from theology and design to gilding and varnishing, it is a prized possession for anyone interested in the traditional arts. The chapter being serialized over the next weeks is called “Designing Icons”. You will see why Archimandrate Vasileos of Iviron called this book the “Confessio of a man who epitomizes the liturgical beauty of the Orthodox Church”. More details about the book on Aidan’s website.

____________________________________________________________

This is part 6 of a series. Part 1, Part 2 , Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 (In this section, Aidan explains the typology of faces and facial expressions in iconography.)

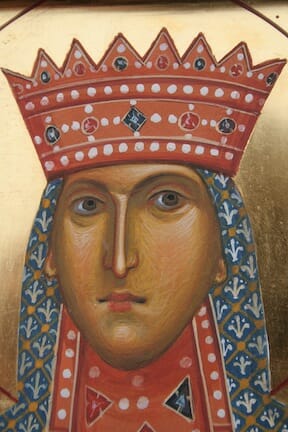

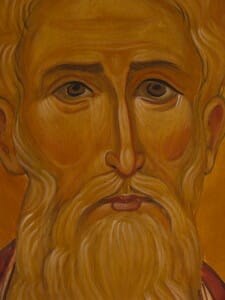

Symbols and gestures in an icon indicate a saint’s role, while the face – the eyes, lips and brow in particular – offers a more subtle indication of their character. Whilst icons are not naturalistic, their faces ought to express something of the saint’s more salient qualities.

Of course a holy person possesses many virtues, but one or two tend to be particularly conspicuous. For instance St Isaac the Syrian is known for his compassion and intense inner life of prayer, and so his face combines sunken cheeks with compassionate, slightly sad eyes.

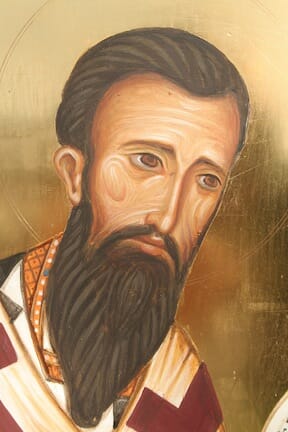

St Basil the Great is renowned for his wisdom and intelligence, which is suggested by his large forehead.

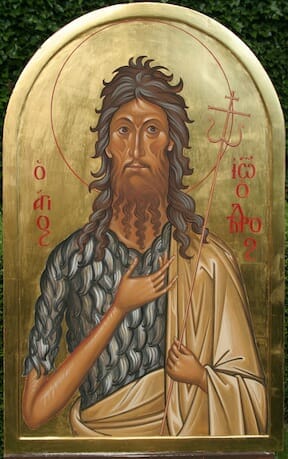

St John the Baptist is known for his prophetic voice and asceticism – hence his wild hair and gaunt features.

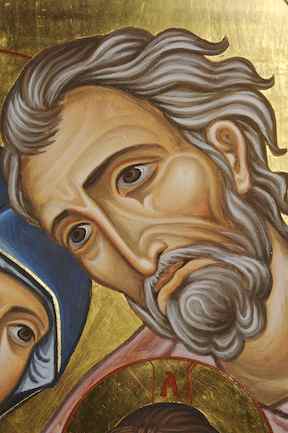

The two eyes and brows can be depicted differently in a given face in order to suggest two contrasting but complementary states, such as gentleness and power; the sadness of compassion and joy ;

…a forceful intelligence and calm stillness.

The most pronounced examples of this are to be found in frescoes and mosaics of Christ the Pantocrator in the dome. One brow is usually sharply arched as an expression of the Pantocrator’s great power, while the other brow’s more gentle arch expresses His gentleness.

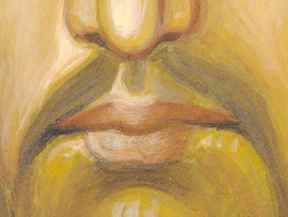

Another common juxtaposition occurs between the eyes and the lips. A light puckering of the eyebrows suggests the sadness engendered by the saint’s compassion for our suffering. To balance this sadness the lips can have a hint of a smile, to suggest inner joy.

Together these manifest what is called in Orthodox spirituality a “bright sadness” or harmolipi, as it is called in Greek. This is a particularly useful technique when painting ascetics. They are normally shown with gaunt cheek bones and taught brows, which by themselves give an overly stern expression. This can be obviated by introducing warmth to the mouth – not a cheesy smile but a deepening of the shadow at the lips’ extremities.

[…] Jan 17th 8:32 amclick to expand…Designing Icons (pt.6): Faces in Icons https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/faces-in-icons/Thursday, Jan 17th 8:30 amclick to expand…immerlein:oldsamovar:Poteryaevka village, Mamontovsky… […]

[…] This is part 7 of a series. Part 1, Part 2 , Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6 […]