Similar Posts

Are There Rules and Where to Find Them?

However, how can we discuss the concept of a list of icon-painting rules if there is the slightest possibility that it might be imaginary? First, let us recall that imaginary entities can define our behavior just as much as physically existing ones. Let us look at the world of written rules. Indeed, the canons of the seventh ecumenical council proclaim the need for icons to be painted, but do not interfere with their artistic execution. Despite its heavy (Roman) legalistic and imperial heritage, the Byzantine Church, as it seems, never attempted a legal codification of its artistic production. The only area where we might find such a thing is in (post-Byzantine) painters’ manuals, which—at some point—actually gave the impression that “Greek” art was executed primarily through obeying prescriptions. However, apart from most of the texts that deal with technical issues, the instructions for the practice of painting are “general canons”— applicable to quite diverse stylistic solutions. Even in the most famous manual, compiled by Dionysius of Fourna, for example, where there is a recipe for mixing the colors for painting the face, and norms for the proportions of the human figure, the author subverts any concept of a rule, since he states that this is only one among many possibilities (although he usually starts with the way of Panselinos). As soon as the reader runs into prescriptions for painting in some other style—Cretan or Muscovite, for example—it becomes clear that the prescriptions are not binding. Thus, apart from the most general rules, for instance, that the icon should be painted in layers (usually from darker to lighter tones), it is hard to find anything more specific in those books. More precisely, we cannot find there any set of direct prescriptions on producing an icon that would be “canonical” in the narrow sense. Moreover, some clumsy attempts to codify any such prescriptions, especially with ever-advancing reproductive technology, has led to cold and sterile results in church art, which could hardly be compared with the genuine achievements of Byzantine art. More specifically, Byzantine forms are recycled, but the spirit, beauty, expression and the sublime…all of this almost entirely evaporates. Unlike its magnificent medieval predecessor, contemporary icon painting seems to be an embodiment of the quotation cited earlier, written by Didron back in the 19th century. Thus, we must wonder: what prevents contemporary icon painters from applying the simple and generalized rules of their craft (which are found in ancient manuals) to create artistic and theological masterpieces truly comparable to those created by their medieval predecessors?

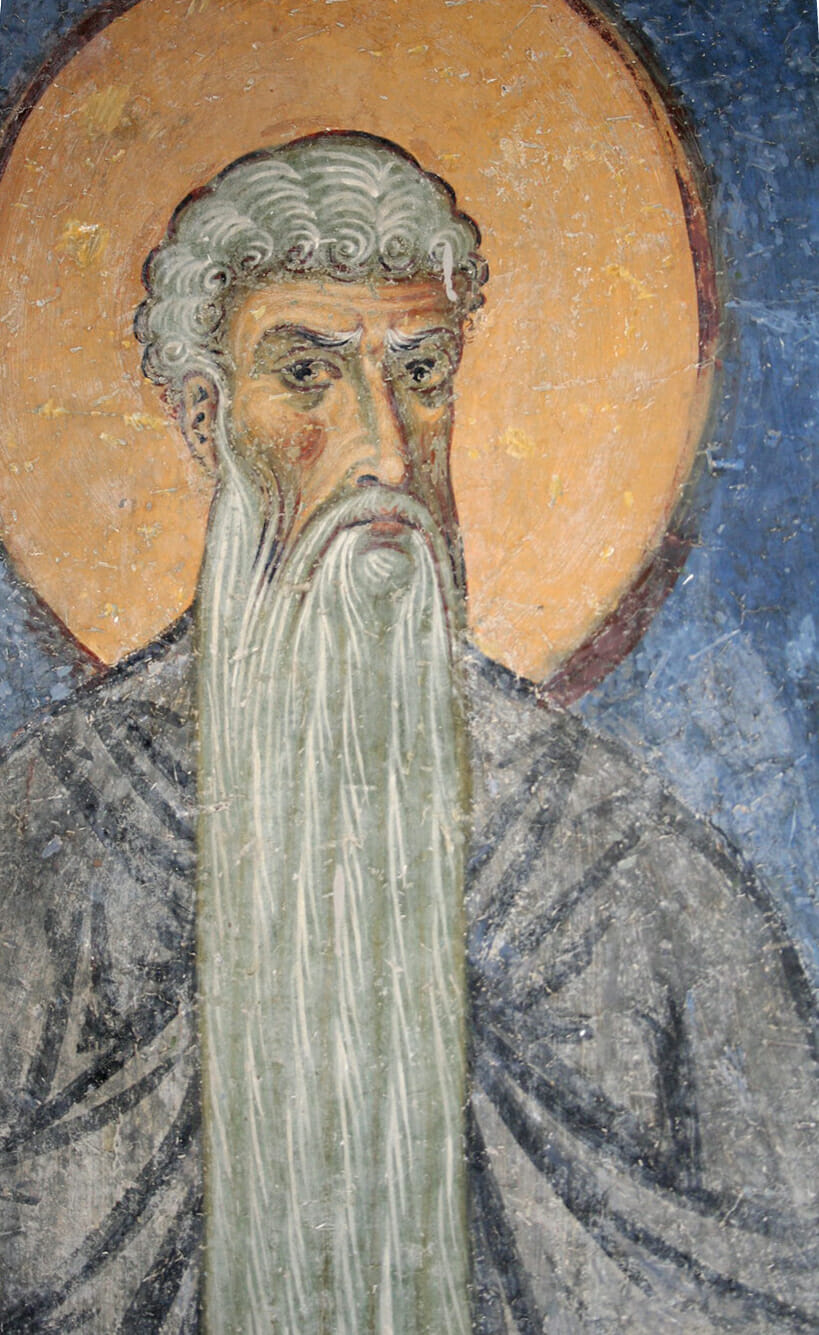

The Saviour With Attentive Eyes, by Dionysios of Fourna, 18th century. Monastery of Koutloumousiou, Mt. Athos.

As we attempt to answer this question, we must necessarily suppose that, alongside the few rules that have been written, there must have been some other knowledge, which was not consigned to writing. This knowledge might be an unwritten painters’ tradition, for example. Since the tradition, as we generally agree, was broken at some point, then it is no surprise that it is not easy to revive it. On the other hand, it now becomes obvious that exactly the lack of this body of knowledge, which appears to have been quite massive, is the reason for weak results in contemporary church art—on both the artistic and theological levels. However, does it make any sense to discuss something that seems beyond reach, after what has been said? Since the continuity of the tradition is broken, there is no way to restore its unwritten aspects. Those who could hand them down are no longer alive. Fortunately, unwritten does not mean oral in the context of the subject under discussion.

While theologians, for example, needed to write down their interpretations of theological texts, which allows us to follow not only the development of theology itself, but also the way unwritten tradition has been distilled in a written form, painters have never felt any such need. The reason is simple: both their unwritten tradition and their personal interpretation of the tradition have been “written down” by their brush. Their “unwritten” tradition was inscribed in their icons, so there was no need to write comments on their work. Thus, it would be better to say that the manuals were comments for pedagogical purposes, supplementing the basic pictorial “text” that appears in the icons themselves. Thus, the question of the relation between peripheral and central issues inevitably arises. Maybe we should simply admit that the contemporary search for the set of written rules, proclaimed as the central issue, has only led to the technical scholia (comments) of the medieval past. (This would also be why this literary genre flourishes precisely as the tradition withers, in an attempt to fossilize it.) The unwritten tradition, which, as we have searched through the ancient manuals, was somehow slipping through our hands, exists exactly in what those texts interpreted—the actual pictorial material. In the actual medieval works of art—the icons, the frescoes and the mosaics. While a manual might have been somewhere nearby, and used if the teacher was absent, the medieval student ultimately learned the tradition of church art from watching his teacher paint. Now we can finally define the problem accurately: the unwritten-visual—but not the unwritten-oral tradition—has been broken, and should be restored. The lost language we are striving to restore is, to put it simply, of the visual kind. The only place where this kind of tradition exists, thus, are the actual works of art. Rules, of course, also exist, but the quest for these should consequently be focused in the right direction. Only through careful differentiation of the visual elements that define the authentic forms of those images, and which are persistent through historical developments of Byzantine art, can we find the rules for reading this kind of language. Without the capacity to read this ancient language, reading the ancient painting manuals, as we have just seen, was pointless. Finally, only after we learn to read this language, can we try to write something down in its tradition—to be hagiographers, as medieval authors would put it.

The Potentials of the Belated Linguistic Turn

As a result of our previous discussion, the conceptual metaphor that would help to free the idea of canonicity in church art from its clumsy juridico-technical context—which clearly has not fostered an authentic enlivening of our artistic heritage—imposed itself spontaneously. Therefore, what would happen if the traditional aspect of church art were not designated by the term canon, but by the term language? Now, let us ask this important question in another way: what would happen if the normative aspect of church art were treated in a linguistic manner? This kind of paradigm change is by no means innovative in the domain of humanities, which were marked by various “linguistic turns” throughout 20th century. However, since church art obviously has not recovered from the magical spell cast by Didron back in the 19th century, rethinking it from the perspective of linguistic turn does not seem redundant at this point in its development.

Now, as soon as we think of such a paradigmatic change, we must naturally ask: if church art is freed from the straightjacket of canonicity and if it is grounded on a more fluid linguistic model, will it not forget its own tradition? The early history of the concept of canonicity suggests quite a different possibility. The word canon (then), similarly to the word language (today), are typically used in the singular, denoting the living and delicate inter-social structures, which are radically defined by their traditional aspect. As a model, linguistic structures might be, thus, beneficial because they are quite alive and open. At the same time, they are defined by norms that are deeply attached to their own tradition. This is why languages do not die easily, but are not easily revived either. It is not some stubborn conservative ideology, but the need to communicate that determines that spoken languages are highly conservative structures. After all, even the contemporary artistic culture, which has left far behind the tradition of avant-garde rebellions against every existing (or imaginary) rule, does not have any problem in understanding that, without some kind of “rules of the game” preinstalled in some kind of historical context, no kind of communication can work. In other words, the concept of linguistic turn is not automatically hostile towards rules and tradition.

If, then, we approach it from such a linguistic perspective, the traditional/conventional and artistic/expressive aspects of church art can finally be put together in a theoretical framework. This will allow them to function unobstructed, but organically. We must stress again that linguistic structures are extremely conservative and slow to change, not because of some ideology, but because of the need to communicate and understand. Changes in language occur slowly because language is not anyone’s private property. Therefore, it does not bend to any whims of an individual. Someone might designate a chair by the term apple, or apple by the term chair, for example, throughout his/her entire life. At best, any potential listener would laugh at such a person. At the same time, spoken language is a wondrously dynamic structure, constantly twisting and turning, allowing individuals to express their thoughts in a genuinely innovative way. Thus, each generation can gradually reshape the very structure according to the needs of its own era.

This supports the idea that such a metaphorical model more closely fits the needs of (theoretical framing of) church art, from both the ecclesiastical and artistic perspectives. Therefore, instead of some extravagant (or avant-garde) exchange of terms for chair and apple, I would suggest a delicate shift in paradigm, which would be much more functional for the needs of contemporary church art. Although the terms canon and language have some semantic affinity, their use as paradigms, in the end, might have quite a different impact on the development of church art. This hypothesis is the key reason for this entire discussion. Therefore, I will argue for it in the following section.

I had the joy and honor of publishing about 15 books on classical and contemporary iconography back in the 1970’s under my publisher name of Oakwood Publications. These included an authorized reprinting the Painters Manual of Dionysius of Fourna, and the Iconography Patternbook in the Stroganov Tradition and others. Most still available from places like St. Vladimir’s Seminary and Amazon. But watch out for the price gouging from Amazon! Used copies are usually available.

Dear Mr Tamoush do you have any information about Paul Hetherington (eg. is he alive, if yes how could I have a contact with him). That would help me in my research about St Petersburg’s CG708 the manuscript on which is based his translation in English. Thanking you in advance! Dimosthenis Avramidis / Associate Professor-Art and Technique of Mural and Icon Painting / Athens School of Fine Arts

This makes a lot of sense. The natural need to communicate and to understanding will keep us grounded. If we visually/artistically try to communicate via arcane systems of meaning, we are hardly communicating at all. Rather we are laying a puzzle before our viewers, which they may or may not have the tools to decipher. In the best case, understanding may be achieved intellectually by the viewer, but not without a loss of salvific beauty and clarity. I think there is a strong parallel here to how we approach adapting Church music in missionary contexts as well.